Featured

6 Photographers Reflect on Robert Frank’s “The Americans”

Dawoud Bey, Kristine Potter, Alec Soth, and more consider the lasting impact of Frank’s groundbreaking photobook.

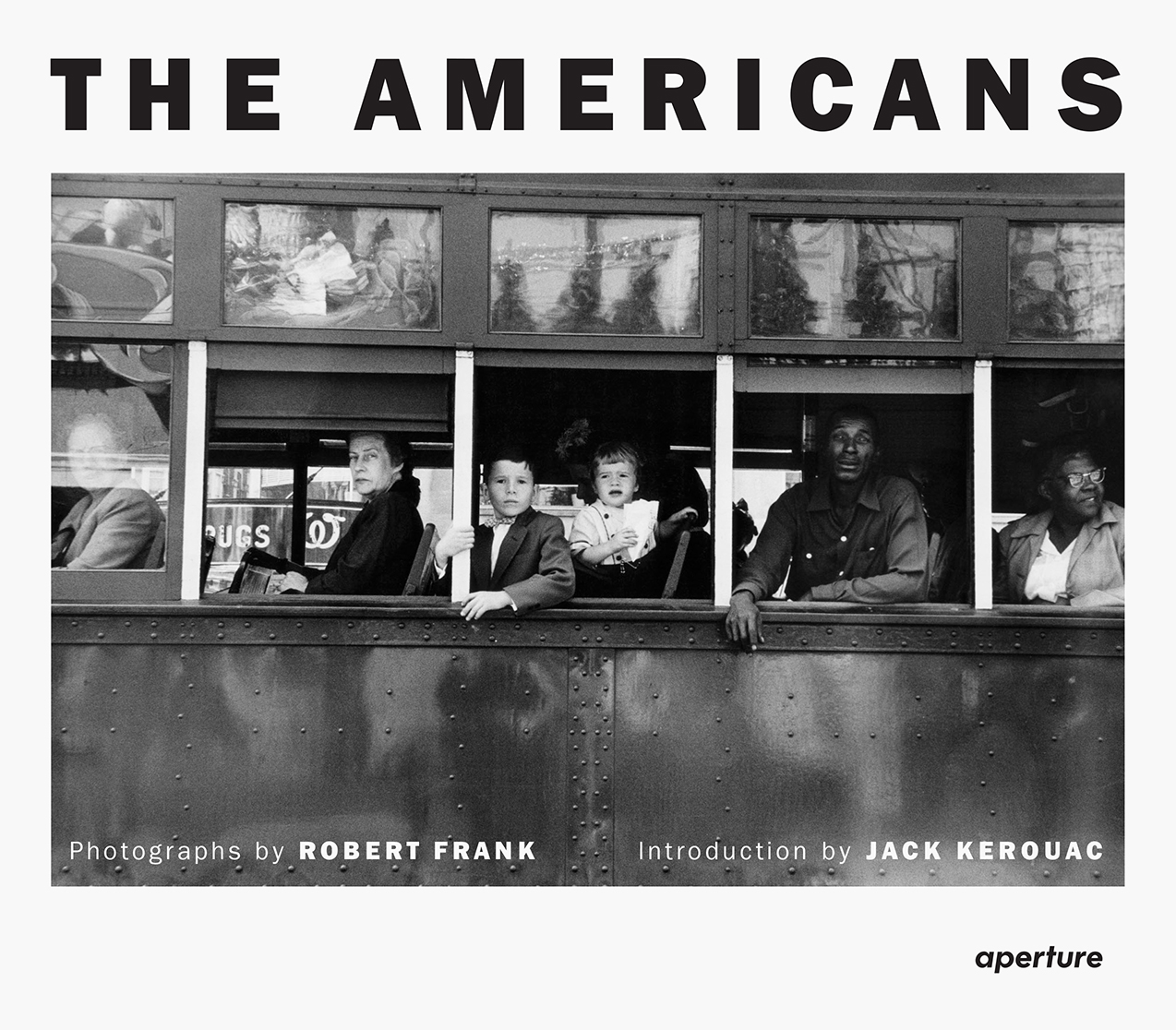

In the nearly seven decades since its publication in France in 1958, then in the US in 1959, Robert Frank’s The Americans has become one of the most influential and enduring works of American photography. Through eighty-three photographs taken across the country, Frank unveiled an America that had gone previously unacknowledged—confronting its people with an underbelly of racial inequality, corruption, injustice, and the stark reality of the American dream. Frank’s point of view—at once startling and tenacious—is imbued with humanity and lyricism, painting a poignant and incomparable portrait of the nation at a turning point in history.

This year, to mark the centennial of Frank’s birth, Aperture has reissued The Americans more than a half century after the 1968 Aperture and Museum of Modern Art edition. This year’s publication coincides with the major exhibition Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Now extolled as one of the most groundbreaking photobooks of all time, The Americans remains as powerful and provocative as it was upon publication and continues to resonate with audiences today. Frank’s exacting vision, distinct style, and poetic insight changed the course of twentieth-century photography—and influenced generations of photographers. Here, six artists choose a photograph from The Americans and reflect on its lasting impact.

Dawoud Bey

Through his now famous journey of absolution across the US that he undertook beginning in 1955, Robert Frank sought to take the pulse of America visually. In the induced optimism of the postwar Eisenhower era, Frank saw, with the unvarnished X-ray vision of an attentive newcomer, beneath the veneer of that era’s optimism to see an America beset by social tensions. For one thing, the troubled relations that the country had with its Black citizens—a continuing legacy of slavery—still rested heavily on the landscape. But then, so did those occasional moments of celebratory release, leisure, and self-celebration, such as one he found as a Black woman ended her day one evening in an open field. The sun was beginning to set, and this lone Black woman was reveling in her moment of release from her labors and cares. She found herself a moment of sheer reverie and was witnessed in this moment by a meandering stranger of a decidedly different race and circumstance, who nevertheless in that instant made an image that imbued her presence with an internal lightness and gestural elegance that spoke—and still speaks—to her deeper sense of self.

Tommy Kha

This is the first Robert Frank picture I saw in a lecture (Ellen Daugherty’s “History of Photography”). Drug Store—Detroit depicts different kinds of divisions: race, class, but also photographic composition. Every element in this picture is occupied. The eye is redirected constantly—from the multiple, semi-deconstructed orange advertisements suspended in the air to the stark contrast between the waitresses and the row of patrons sitting at the counter. The picture’s only breathing space, next to the women of color behind the counter, is quickly disappearing.

Viewing this image, I want to recall my fondness for the late Wiles-Smith Drug Store in Memphis. This drug store had a lunch counter serving the best tuna melts and shakes and was an echo of bygone days. While I would prefer to idealize these communal spaces and the shared experiences around food, I can’t help but be haunted by the uglier moments the past can evoke and its divisions that persist today in plain sight. Frank’s photograph remains a cautionary tale.

Ari Marcopoulos

This is a view of life where a worker’s productivity is all that matters. Working in twenty-four-hour-a-day shifts till your body simply can’t do it anymore. The modern serfs living under kings. The American dream disassembled in one image. The American dream is, in fact, a nightmare.

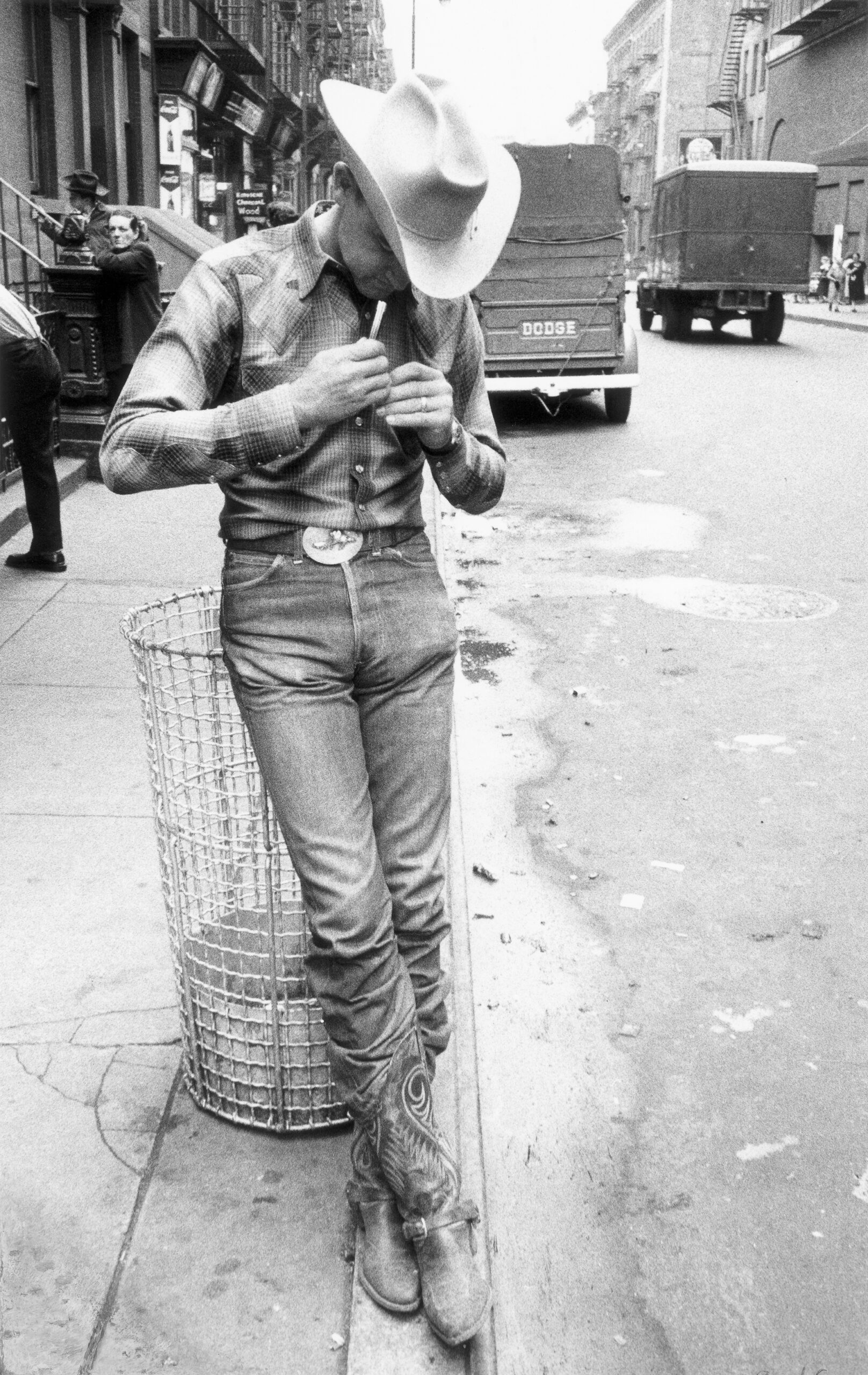

Katy Grannan

I remember where I was standing and the quality of the light the day I first picked up the book that changed everything. There was a before and after, and all the revelations in between its pages were so powerful that I walked away from a career in medicine and chose photography instead. I had never seen anything like The Americans—the poetry, the formal intelligence, the unrelenting critique, and the humanity of Robert Frank’s work were so beautiful and messy and unafraid. Words are a poor approximation, but since Aperture asked, I’ll say this photograph of a cowboy leaning against a trash can is something else. Its meaning only starts within the frame—the cowboy’s tight-fitting jeans are carefully tucked into hand-tooled boots, his long legs extended and crossed casually as though anticipating an audience. It seems the Marlboro Man has lost his way, his horse replaced by a trash can. Never mind the concrete backdrop, this wayward mythic figure is a Believer, attending to every sartorial detail, gesture, and pose.

Kristine Potter

There’s much to admire in The Americans, but I’ve always particularly loved the portrait of the cowboy in Rodeo — New York City. Frank captures a moment of dislocation—a man dressed in the rugged attire of the American West, standing alone on a city street. His cowboy hat, boots, and belt buckle evoke the myth of the fearless, independent figure, yet here, he seems out of place. His head is bowed, hands adjusting his shirt in a small, vulnerable gesture that contrasts sharply with the boldness we associate with this iconic role. The urban environment surrounds him, indifferent to his presence, while he remains isolated from it, leaning against a wire trash can as though caught between worlds. I’m particularly drawn to the tension between myth and reality, which runs throughout Frank’s work. He reveals how twentieth-century symbols like the cowboy, the car, and the drive-in unravel—whether through shifts in context, changing cultural landscapes, or because the myths were always fragile. Yet, in stripping away the layers of these American ideals, Frank was not only exposing their complexities but also deconstructing them. Frank was perceptive enough to recognize these symbols even as they were being formed.

Alec Soth

Like countless photographers inspired by Robert Frank, I’ve visited Butte, Montana, and been seduced by its faded western grandeur. I’ve even made the devotional pilgrimage to the room where he took his picture at the Finlen Hotel and Motor Inn. Needless to say, the picture I took wasn’t memorable. What makes Frank’s image special is less what’s described than the aura of its author. The somber hotel view has depth because we step into the shoes of the road-weary traveler.

See more in Robert Frank: The Americans (Aperture, 2024).