Featured

A Photographer’s Unsettling Experiments with “Cursed” Images

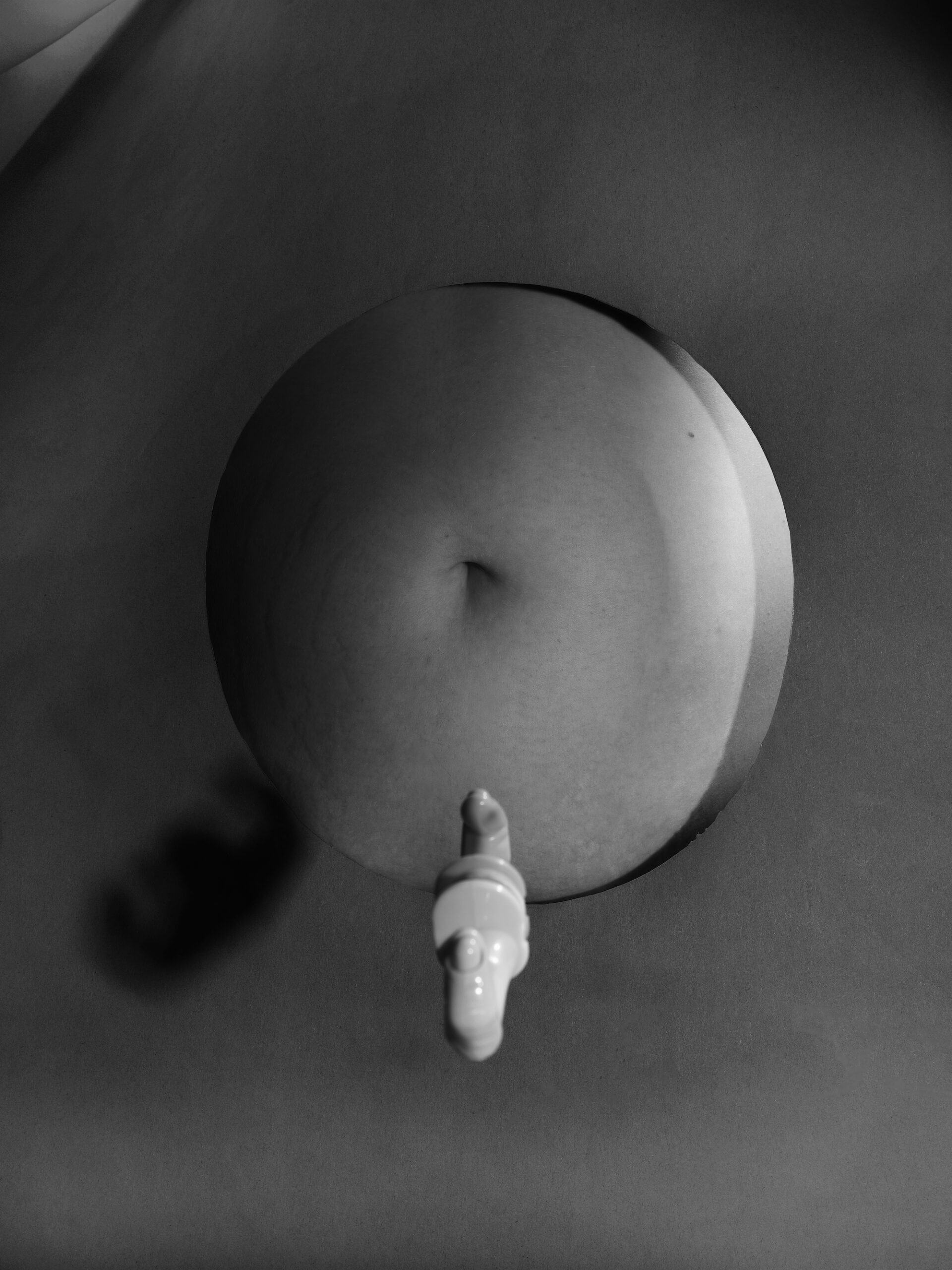

Patricia Voulgaris employs the visual language of the supernatural, tracing the tenuous line between belief and doubt.

Picture an ’80s suburban, pastel bedroom with a life-size Elmo beckoning you to join him on the bed. One image shows two toddlers in a playpen lurching toward a medieval sword. In another, a raccoon, adorned in lilac frills, is dancing with its hands in the air while six snails drink milk together from a heart-shaped dog bowl. These are #cursedimages, and in 2016 social media was littered with them.

Defined by their lack of origin and mysterious content, #cursedimages intentionally create confusion. They juxtapose the aura of vernacular photography with uncanny and incongruent elements—in the same potent way nightmares scramble your deepest fears with daily events. The result is a toxic push-pull that leaves you disturbed by their chaos and soothed by their familiarity.

#cursedimages began as a visual shorthand for a bad day and transitioned into a viral phenomenon describing our collective psyche in a year of dramatic social and political upheaval. As they began to shift format—from images to memes, memes to TikToks—they became more feral. Eventually, #cursed took on greater cultural significance, emancipating itself from form and representing a moment in history. In the 2019 New Yorker article “How We Came to Live in ‘Cursed’ Times,” Jia Tolentino writes, “The idea of cursed energy does evoke a feeling that the simulation is breaking and that something terrible is emerging from the breach.”

The psychological impact of #cursedimages is a source of much fascination for photographer Patricia Voulgaris, who examines how we put our faith in images and the consequences of this trust. “I’m interested in what makes an image cursed or thinking about myself as being cursed,” she tells me over the phone. “I tried to curse myself for my final, and it did not go over well. Some people don’t believe in the possibility of phenomena.” Voulgaris, an MFA student at the Yale School of Art, is drawn to the fringes of belief and doubt, giving as much credence to the ridiculous as the serious, which, in part, makes her work feel inherently more human.

Photography’s role in cultivating systems of belief is something Voulgaris has been meditating on for years. As a teenager growing up in Levittown, Long Island, she spent Saturday afternoons ghost-hunting with her father. He was an active member of Long Island Paranormal, a Facebook group that met regularly in local cemeteries and haunted houses, hoping to connect with the spirit world. Armed with cameras, sound recorders, and electronic-voice-phenomenon meters, the group would trawl a location, often walking for hours, seeking evidence to confirm their beliefs.

“It felt like a social experiment,” Voulgaris says. “Trying to find proof but profoundly insecure about what would happen if we did. How do you capture an event to debunk a theory? More importantly, how do we create a false narrative that is believable? I am interested in how photography can lead viewers to arrive at a sense of certainty within themselves. It’s ultimately about searching for something concrete in a world that makes no sense.”

In her latest photographs Voulgaris employs the visual language of the supernatural, taking as her subject the tenuous line between belief and doubt. She collates constructed and caught moments, merging clichés and the mystical to express her ambivalence about both the spirit and the human realm. Voulgaris describes her process as a “response,” enabling her to move “through ideas and move more freely” in a continually iterative practice as opposed to focusing on a resolved body of work. Her intention is to create images as feelings, trading in the world of symbolism and the haptic rather than definitive narratives.

The notion of illusion and perception in a post-truth era has shaped much of Voulgaris’s recent work. In her previous series The Hunter (2020–ongoing), she grapples with the persistent threat of violence to which women are subjected every day, and how it is normalized in our culture. She enlists her partner and parents as protagnosists, crushing and contorting them in bizarre and haunting scenes that resist explanation. Similarly, Voulgaris’s new images fuse constructed moments and improvisation to elicit the same unsettling sensation, this time grounded in unexpected encounters with the natural world.

While Voulgaris’s photography is rooted in a genuine fascination with the supernatural—nineteenth-century spirit photography, mediums, unexplained events, and projects like Mike Kelley’s Ectoplasm Photographs (1978/2009) are all vital touch points—it also functions as a crutch and a trick. It’s a way to capture the viewer’s attention and draw them into a conversation about something more complex.

At its core, Voulgaris’s work is about the stories we tell ourselves and our tendency to focus on what we want to see rather than what’s in plain sight. Photography has been an accomplice in self-deception, deliberate mistruths, and comforting lies throughout history. In a subversive gesture, Voulgaris illuminates our obsession with certainty while asserting how powerful it is to own the difficult complexities of our existence rather than deny them.

Patricia Voulgaris’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera.