Introducing

A Photographer Who Built a Career Through Listening

In Bangladesh, Sarker Protick combines the impulses of a photojournalist with the intuition of a musician, unpacking questions about photography’s relationship to time and memory.

Sarker Protick found photography through music. Growing up in Dhaka in the 1990s, he remembers his mother’s fondness for singing and his father’s love of the Doors, Leonard Cohen, and the Beatles. “My father wasn’t a musician,” he recalls. “But he was a very good listener.” In college, Protick learned to play guitar and then the piano, formed a band, and began writing his own music.

Photography was merely a hobby then, a way of documenting life in college, his friends, and his city. After some encouragement from an uncle who saw his pictures, Protick decided to enroll in night classes at the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in 2009. Established in 1998 by the photographer and activist Shahidul Alam, Pathshala was (and still is) unlike any other institution in South Asia, founded with a strong documentary focus. When Protick arrived, he was surrounded by photojournalists from the region, but it wasn’t until he saw the work of Robert Adams and William Eggleston, another photographer-musician, that he felt a deep resonance. “This is what photography can also be,” he recalls thinking. “This is what I wanted to create.”

Protick splits music and images as two distinct parts of his journey as an artist, but over the last fifteen years—and across projects spanning photography, video, and sound—he’s built a career out of listening. His work uses historical frameworks rooted in Bangladesh and the wider Bengal region to unpack questions about photography’s relationship to time and memory. Combining deep research, a patient eye, and an intuition for visual rhythm, his approach negotiates the impulses of the photojournalist with those of the musician. “Musical composition is such an editorial process; you build a logic through it,” he says. “That selectiveness is vital, and it came to me naturally as a photographer.”

Protick’s compositions are quiet and spacious, inviting a wide field for association despite their highly specific context. In one of his earliest series, Leen (Of River and Lost Lands) (2011–ongoing), he photographs the Padma River that cuts through Bangladesh. Waterways dominate the country’s topography, and the river is embedded into its national and cultural story. In college, Protick read the novel Padma Nadir Majhi (The Boatman of the Padma) by prolific Bengali writer Manik Bandopadhyay, which exposed him to the narrative potential of the river, an artery signaling both life and destruction.

He later drew a connection to the American highway, and the work of Robert Frank, Ed Ruscha, and Stephen Shore from the 1950s to ’70s. “In the US, the entire country is road,” Protick says. “But it’s not the same here. The traveling mode is the river, and it’s always been the lifeblood.” On the riverbanks, land and livelihoods are at perpetual risk of being swallowed up by flooding. Over multiple trips, Protick observed the Padma’s eroding embankments with great care, using a subdued photographic palette to represent the calm yet alarming ticking of a geological clock.

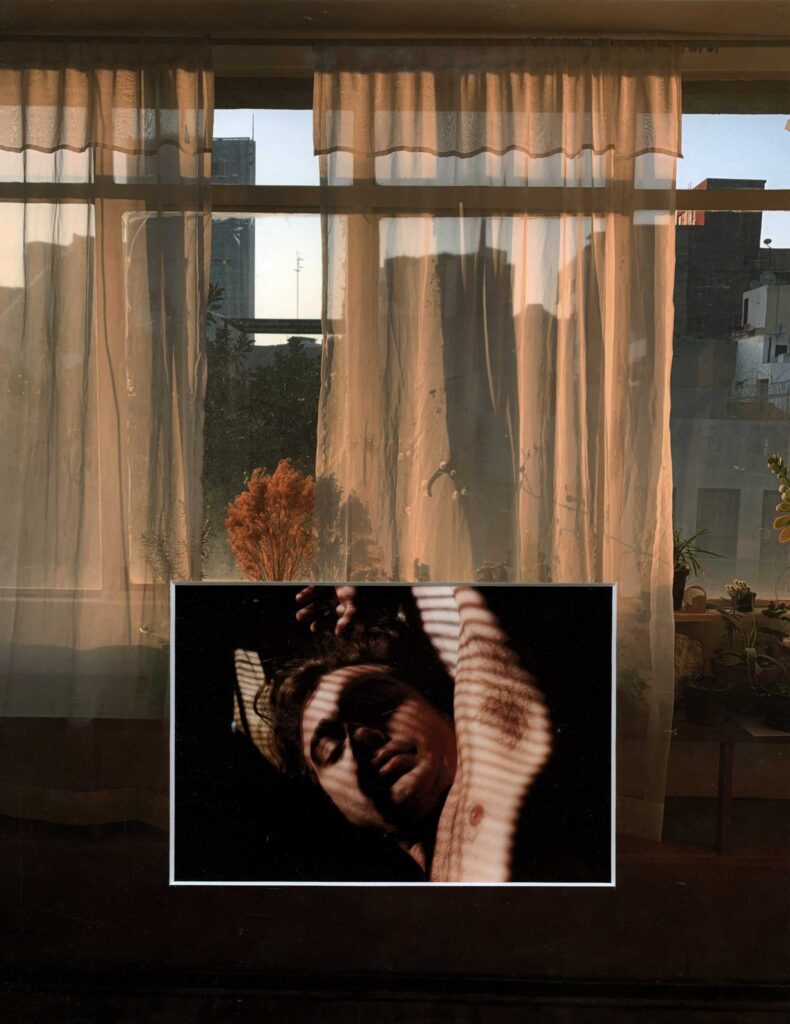

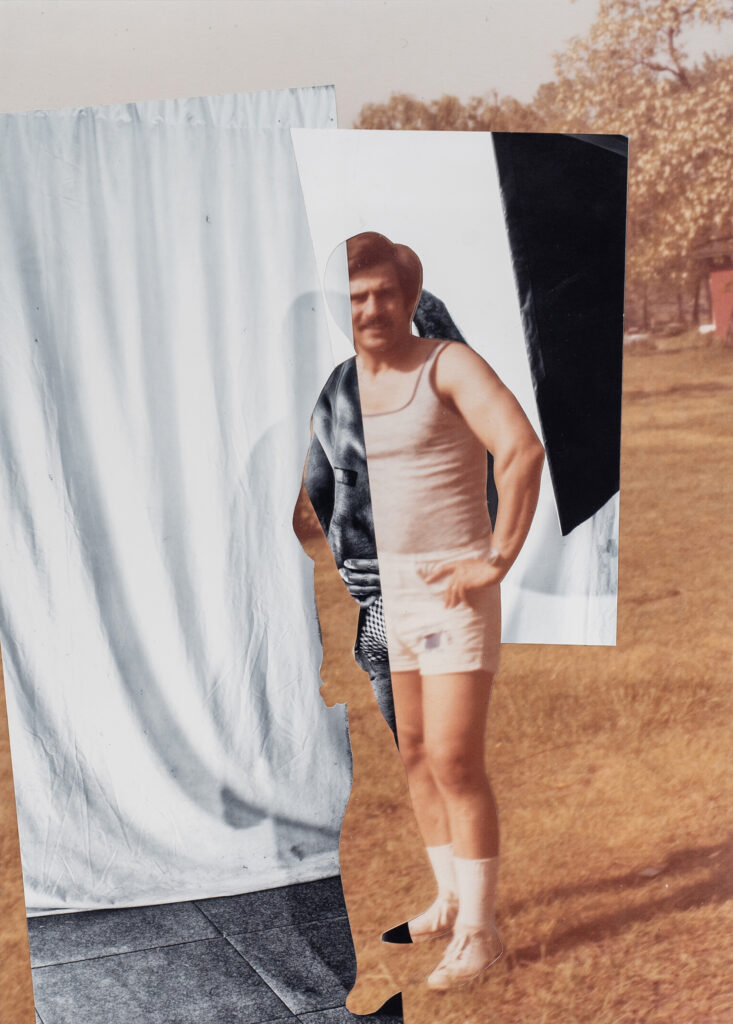

In the series Mr. & Mrs. Das (2012–16), Protick telescopes into a single apartment in Dhaka, where he photographs his aging grandparents in their final days. His images of sparse interiors contrast with archival imagery of his subjects’ life as a young couple. The whitened, near-clinical palette reappears, isolating seemingly nondescript objects—telephones, vases, frames, loose wires, suitcases—to tell a larger story through fragments. As on the river, Protick attempts to grasp time’s pervasive crawl, and from this stillness honors the ordinary, intimate details that furnish a shared life.

Nature, memory, and time gradually became thematic tentpoles for Protick. His video work Raśmi (2017–20) projects these ideas onto a cosmic scale. A montage of images creates a constellation of flashing associations between light and dark, abstract and figurative scenes, and planetary and microscopic degrees—all layered over music composed by Protick himself. We move from lightspeed to the lumbered march of historical time in the series Jirno (2016–ongoing), meaning “ruins” in Bangla. Here, Protick uses serene, long-exposure compositions to depict abandoned feudal estates, once owned by Hindu landlords from pre-Partition Bengal, now decayed and returning to the landscape.

The images, shot in black-and-white and often in hazy conditions, force dense greenery to flatten against the buildings’ architectural contours. “There’s always an extra thing happening, even in a very static, still moment,” Protick says of his approach. “Nature becomes more present in the photograph.” The colonial-era buildings stand as frozen testaments of the region’s transformation (or lack thereof), and the place of the past in the present. If the story of Bengal over the twentieth century is in some ways the story of migration, Protick mines for what is left behind.

The marks of movement reemerge as a theme in Ishpather Poth (Crossing) (2017–23), which traces the built legacy of the Bangladesh Railway, once part of the sprawling train network that traversed the historical Bengal region. Following two partitions—of India in 1947 and Pakistan in 1971—many lines on the railway were severed from their ends. As in Jirno, Protick expresses historical time through the stoic language of the built form; industrial remnants of colonial rail workshops and power stations, abandoned offices and bungalows, and aging railway towns.

In one image, the steel mouth of the Hardinge Bridge opens into a mile of track over the Padma. The bridge—which evokes the twin legacies of colonial engineering and the Bangladesh Liberation War—also appears in the Leen series, this time from the perspective of the Padma below. Both projects brought Protick back to the Pabna District in central Bangladesh, home to one of the largest railway junctions in the country, and to the Padma. “Every time I finish a project, I somehow find a layer for another,” he says.

Take a step back and a greater tapestry emerges. The river, the ruin, and the railway become interconnected protagonists in a story spanning centuries and national borders. Protick’s latest series, Awngar (Ash to Ash) (2024), recently exhibited at C/O Berlin, adds another layer. Made across modern-day India and Bangladesh, the series explores the linked development of railways and the coal mining industry under British rule. Its images and video works are characteristic of Protick’s style, atmospheric and rich in allusion. Landscape views of marred coal mines and videos of explosions juxtapose more meditative scenes of mining offices and coal-black surfaces. Predatory capitalist and colonial extraction have mercilessly shaped Bangladesh’s ecological reality, the series argues. “Awngar” is the Bengali word for coal in a red-hot state, ready to combust, and the series associates this catastrophic, latent energy with imperial and industrial ambitions in the region.

Photograph by David von Becker

Photograph by Jens Gerber

Memory is difficult source material. While many of these explorations are historically embedded, they raise universal questions about the power of the image to illuminate a place. These questions do not end behind the camera for Protick, who has been on the faculty of Pathshala since 2013 and acts as the co-curator of Asia’s longest-running international photography festival, Chobi Mela, which will return for its eleventh edition this December, in Dhaka. Across his work, Protick frames the past with the present, where looking constitutes both remembering and recomposing. Robert Adams once said of his forty years of work on the American West, that, “by looking closely at specifics in life, you discover a wider view.” In his stillness and attention, Protick composes his own.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.