Portfolio Prize

Alana Perino Crafts a Haunting Story of Family and Memory

In the Florida island town of Longboat Key, the photographer—and winner of the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize—portrays a home upended by loss.

In a spare, domestic tableau, a bare-chested older man sits pensively on the edge of a nightstand. He looks down at a white bird resting on his hand as a lamp casts light across his body and an empty mattress. Above the bed, a small wooden frame holds a painting of an angel.

The figures within this image—man, bird, angel—permeate Alana Perino’s Pictures of Birds (2017–24), an elegiac series of photographs that searches for meaning in memory and mortality.

Perino, who was born in New York and raised by separated parents, finds home in many places. In 2020, they moved to live with their father, Joe, and stepmother, Letty, on the small Floridian island known as Longboat Key. Perino had begun to photograph their family in the Longboat Key condo a few years earlier, as they noticed Letty first experiencing symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer’s. By the time Perino relocated to Florida, Letty’s condition had worsened.

In these years, their sense of home was upended along with the “strange, unwritten contract of the family,” as Perino put it. Letty was younger than Joe, and ostensibly would have cared for him as he aged; now, new family roles formed in which Perino and their sister became caretakers of their stepmother. “The entire island became this eulogized space,” they said. “Everything began to represent her death.”

At night, Letty would speak aloud in the room Perino shared with her. “I realized, after many nights, that she was talking to the same people in the room,” Perino said. “She was talking to ghosts.” Pictures of Birds does not shy away from the idea that spirits dwell in this home, and in many ways, the photographs take comfort in their presence. Perino’s family on their father’s side is Catholic, though the photographer was raised Jewish; in the spiritual treatment of ancestral remembrance and protection, they find common ground among traditions. Outside Longboat Key’s Catholic church, Perino photographs the three wise men conjured as statues shrouded in plastic, an uncanny scene mediating the animate and inanimate.

Perino’s sense of home was upended along with the “strange, unwritten contract of the family.”

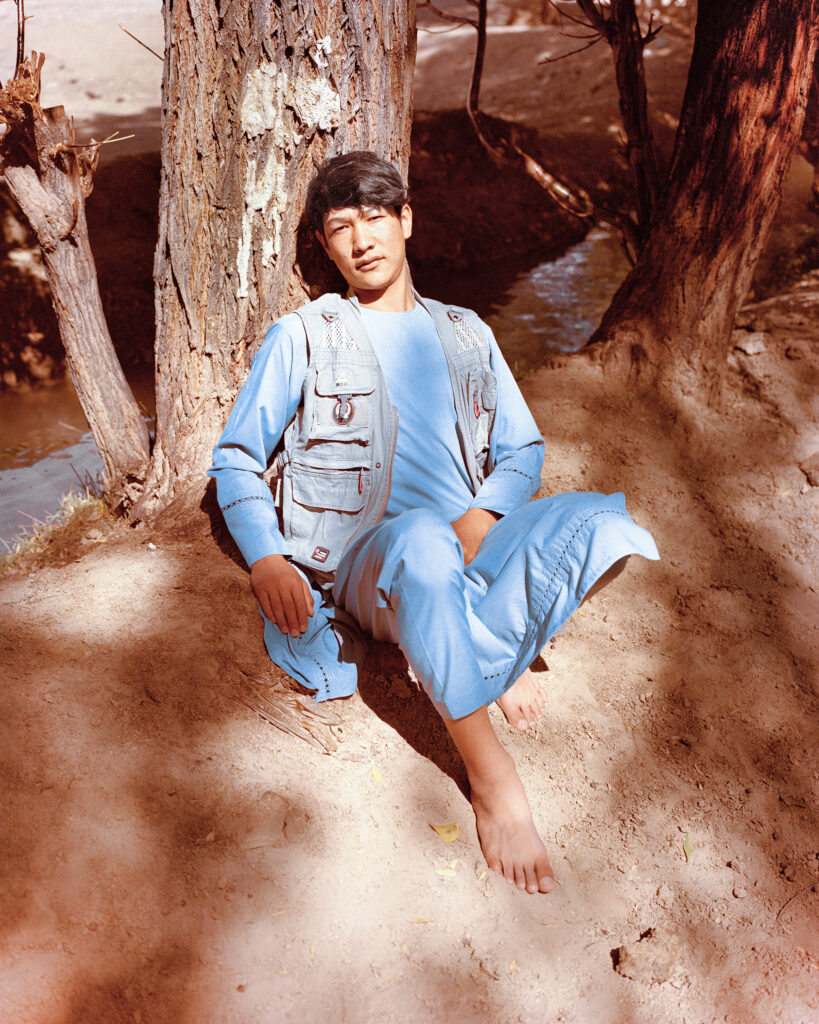

Letty died in 2021. Perino continued to photograph their father, sister, niece, and a few other family members until 2024, when their father sold the Longboat Key condo and moved away. The later photographs resonate with the loss and Letty’s continued presence in their lives. A portrait of Perino’s niece Madi floating in a pool recalls an earlier photograph of their father, though where his face turns toward the sky, Madi’s is obscured by her hair as she looks down into the water. In a self-portrait, Perino, eyes closed, lays on their back in a pit dug in the sand on a beach.

Letty would repeatedly ask Perino as they photographed around the house, “Why don’t you take pictures of birds?” After all, that is what most people do on Longboat Key. Perino initially decided to photograph anything but the flamingos and egrets of Sarasota County. In time, they came to understand everything they photographed as birdlike, every portrait as a self-portrait. The mutability and fluidity of corporeal figures was never more apparent than in the countless seashells cast aside on the shore. Letty had collected shells for years; Perino viewed them as an extension of nonhuman ghosts, long discomfited by the removal and disruption of a creature’s life cycle. They eventually photographed the shells, too, and made excursions around the island to photograph a wider perspective: the ocean, statues, a shark living in an aquarium.

“This is when the project really began to expand from this notion of memorializing a really sad event for our family that was prolonged and changed the shape of all of our roles, to a kind of internalization of these realities, of our lived everyday experience with the dead and their presence in our home,” Perino said. “How all of these ecosystems—and this particular ecosystem within Longboat Key, the humidity, the scope of life—it highlights how interconnected all of the different species are and how reliant we are on the shells, the mangroves, the water, and even things like the aquarium to survive and to proceed from one generation to another.” Perino’s photographs rarely depict Letty, who resisted the camera’s presence. In one of her few appearances, only an out-of-focus glimpse of a hand at rest is visible in the foreground. The picture’s title, Nina’s Afghan (2020), refers to the shawl made by Perino’s grandmother and draped over the back of a chair. A painted portrait of their father and Letty hangs on the wall above the chair, their faces just out of the photograph’s frame. Nobody ever sat in that chair. Instead it stayed empty, an outsize and invisible presence filling it, a ghostly apparition just out of reach.

Courtesy the artist

Alana Perino is the winner of the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize. A solo presentation of their work will be organized by Aperture in New York City.

This piece appears in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads,” Summer 2025.