Interviews

Alejandro Cartagena’s Prolific Career as a Photographer and Editor

For over two decades, the Mexico-based artist has produced a compelling network of inquiries about social, urban, and environmental issues in Latin America.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, Spring 2023, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live,” in The PhotoBook Review.

Alejandro Cartagena does a lot. He is a photographer. He is a publisher at Studio Cartagena and a copublisher, with Carlos Loret de Mola, at Los Sumergidos, a small independent bookmaker based in New York and Mexico. He self-publishes some of his own books; others are published by the likes of Skinnerboox, in Italy, and Gato Negro Ediciones, in Mexico. And sometimes he is just the author. He is an in-demand photobook editor and, most recently, as a cofounder of the NFT organization Fellowship, is deeply involved with the NFTs scene. Cartagena’s overall practice as an indefatigable bookmaker—thirty-three books and counting—has produced a compelling network of inquiries about social, urban, and environmental issues related to Monterrey, Mexico, where he lives, and to Latin America in general. His work is at once geospecific and universal, methodical and loose, empirical and poetic. One morning in 2022, during Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair in New York, the publisher Bruno Ceschel met with Cartagena to try to make sense of it all.

Bruno Ceschel: I want to start with your practice as a photographer. It looks to me that the methodology you adopt in your work bears a relationship to anthropological fieldwork—in your case, manifesting a structured way of analyzing complex social themes related to your own environment via the close observation of various, but specific, phenomena.

Alejandro Cartagena: I think it comes from my training in visual studies, the idea of understanding an issue by visualizing the causes and effects of it. I would call my methodology a Google-era understanding of photography: if you pose one question to Google, it’ll give you a hundred thousand ways of understanding what you have asked about. I thought that was an interesting way to develop my practice. Yes, I photograph housing developments, but how did those houses get there? What is the bureaucracy behind it, both public and private? After getting those houses, how do people then deal with transportation? What does it look like when you are using public transportation? What does it look like when you are using private transportation? What are the problems that stem from building those houses? There are environmental implications, effects on the waterways, et cetera. I felt this was an interesting proposition for documentary photography, to look at an issue by looking at all the other issues around it, even if they contradict the initial starting point. That vulnerability is very important for documentary photography, because it’s not about truth—it’s about an opinion. It is about making visible different ways of thinking about the same issue.

Alejandro Cartagena: Ground Rules

65.00

$65.00Add to cart

Ceschel: What’s the main issue in your work, then, if you are able to describe it?

Cartagena: In most of my work, I would say homeownership.

Ceschel: But in a specific location, right?

Cartagena: Totally. It’s concentrated in the metropolitan area of Monterrey, which is where I live. I’ve seen the changes to the city caused by suburbanization. It’s a case study of what I was reading about urban theory at that time—how cities grow and decay and grow and decay constantly. It was, I guess, a coincidence that I was reading that kind of literature and seeing it play out in the real world. It was theory being made visible to me in my city.

Ceschel: With a speed that is probably specific to our times.

Cartagena: Exactly. It’s suburbanization on drugs, literally.

Ceschel: While you talk about producing according to a methodology, and being prompted by academic discourse, your work reads to me as an art practice.

Cartagena: I think of my practice as visual poetry—photographs of dying rivers alongside images of people in the bed of a truck; pictures of people renting houses next to images of high-rises and empty lots in downtown Monterrey. The poetry comes from impromptu and open relationships that would be hard to justify in an academic context. In our culture, we have discrete, determined realms where things are supposed to happen. Art is the space where people can let go and do things that don’t make any sense.

I think of my practice as visual poetry—photographs of dying rivers alongside images of people in the bed of a truck.

Ceschel: Or where people can feel, instead of understand.

Cartagena: Feel is important . . . and having no purpose aside from just an escape from order, escape from the idea of the known. It doesn’t mean that all art is that way. But that’s one of the things that I really love about art: I can propose ideas that in other fields would be rejected.

Ceschel: Do you see a sort of chaos as part of the strategy here?

Cartagena: Yes. I remember my first portfolio review, in 2004. One of the reviewers saw my work and said it looked like shit. The photos were really badly printed. He also said, “But there’s a flavor to that. There’s this organic-ness. The ideas are really good, but there’s this unfinished nature to them.” That comment stuck with me for a long time. I am conscious of the organic-ness of a narrative that is never finished in my work, which speaks of how I see Latin America—always in process, never finished.

Ceschel: Some threads in your practice are ongoing: The Carpoolers series is in its fourth volume, for example. And you have often used a book format drawn from various how-to guides—A Small Guide to Homeownership (2020), Guía presidencial de selfies (Guide to presidential selfies, 2018), and A Guide to Infrastructure and Corruption (2017).

Cartagena: The nod to the guide format is important to me because it’s aligned with what photography is supposed to do: document, comment upon, and explain visually. But most of those books are an antithesis of a guide. They are complicated and nonsensical at times. After my master’s in visual studies, I did the first volume of Carpoolers in 2014, followed by the Infrastructure and Corruption book, and a lot of subprojects that were never really completed. The idea of repetition is vital to my practice, not only in the representation but in ideas of themes and design. There’s a big narrative arc that continues through each new publication, sometimes using the same images in different contexts, in different ways.

Ceschel: On your website landing page, there is a list of titles in chronological order. There are your self-published books. There are books of which you are the author, but you’re not the publisher. And then there are books that you edited, which sometimes you publish or others publish. But you present them as a whole. Can you talk about the relationship between your own practice as an image maker and a bookmaker?

Cartagena: The idea of authorship is very interesting to me. When does authorship get fixed in photography? Does it get fixed when you take the photograph? Or does it get fixed when you edit and sequence a book? My website reflects that; I have authorship in all those books even if I might not be the photographer. Editing as authorship is part of my

art practice.

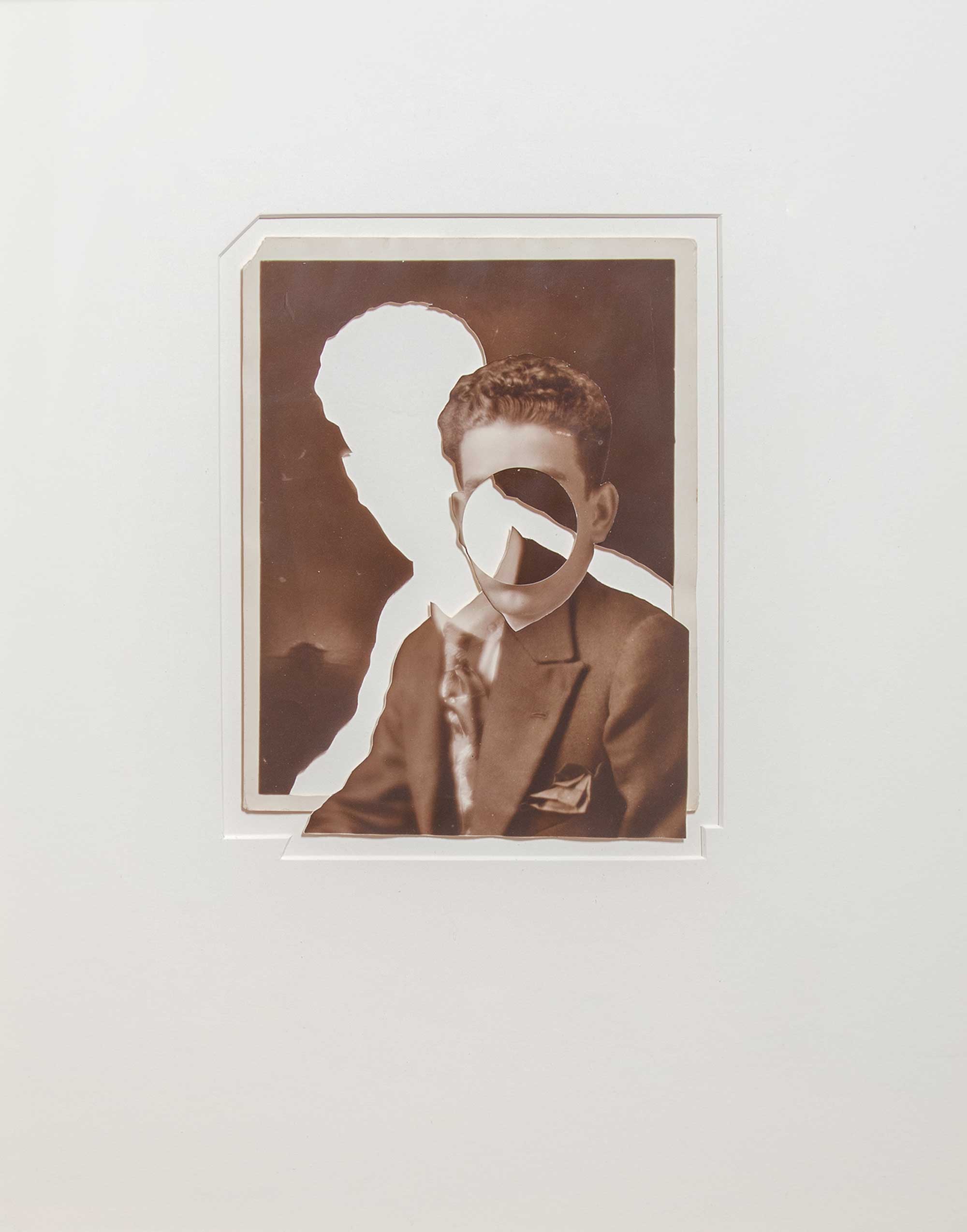

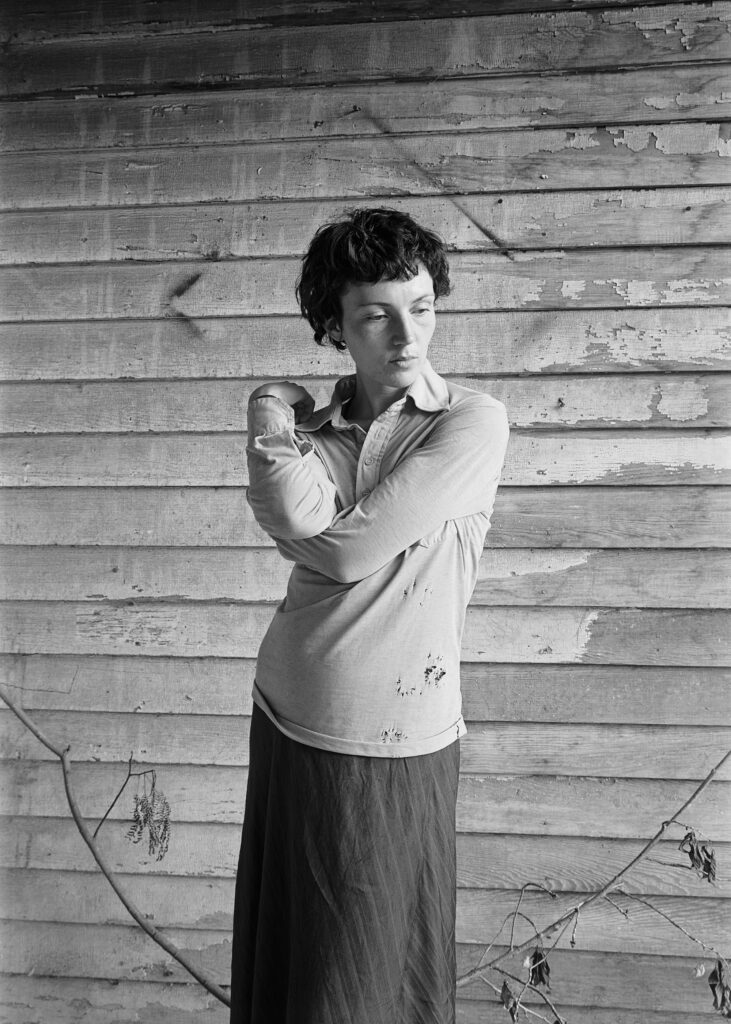

All photographs courtesy the artist

Ceschel: Finally, how does your work in digital spaces, Web 3.0 and NFTs specifically, sit within your practice?

Cartagena: Web 3.0 and the digital space, for me, are a continuation of the idea of expanding photographic distribution. Photography is a medium that needs distribution. It needs to connect with people. And so, what really attracts me to NFTs and the digital realm is the expansion of a collector base. It’s a place to educate, and a new source of people who can get excited about photography. That is something that photography in the NFT world does really well. What changes is the idea of ownership. That’s why, also, I think photobooks work really well, and why there is a bigger market for photobooks than prints, and why there’s a bigger market for NFTs than photobooks. Each offers the opportunity for ownership, but, each time, it’s a broader opportunity. Prints are owned by just a few collectors, books have a little bit of a larger group of collectors, and with NFTs there are even more.

Ceschel: Earlier you said that editing and sequencing are fundamental parts of your work, but with NFTs, all of that is basically irrelevant, as images often circulate on their own and without context.

Cartagena: With the first two platforms for photography, the print and the book, we understand how those outputs work. With a print, we understand the idea of texture, scale, the quality of the paper, the tonal range—you can tell a good print from a bad print. With photobooks, it’s the idea of design, sequence, editing, the materials used. With NFTs, we’re still developing the code for this new mode of output, an understanding of what makes it a unique iteration of the medium—what will make photographers excited to use it in their practice. It’s inspiring to be at the forefront of trying to figure it out.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, Spring 2023, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live,” in The PhotoBook Review.