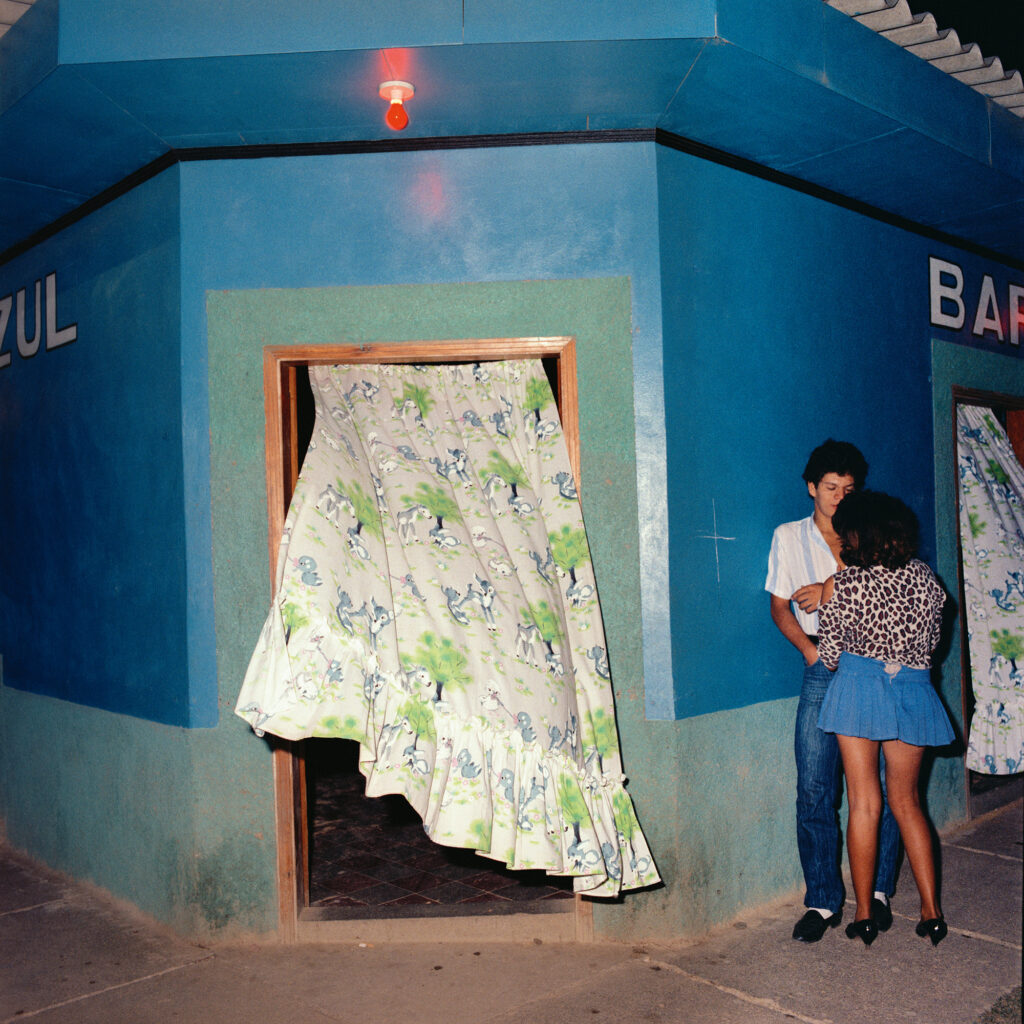

Portfolios

An Asian American Family’s Public History and Private Rituals

In his photographs, Jarod Lew asks his family to reenact scenes from everyday life, invoking stories that wrestle with the tensions between control and care.

Context is rarely tidy. Even as it clarifies, it confounds. Consider this: in 1982, Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two Detroit autoworkers on the night of his bachelor party. In the aftermath, he became an enduring icon of the Asian American civil rights movement. Thirty years after Chin’s murder, the photographer Jarod Lew discovered that his mother had been the one engaged to him. If this is context, I wondered, viewing Lew’s family portraits in his series In Between You and Your Shadow (2021–ongoing), what to do with it?

In one photograph, Lew’s mother hides her face behind a bouquet of bright spring flowers. In another, two vacant chairs sit against the wall of his aunt’s Chinese restaurant in Metro Detroit. I admit I tried to make such images carry the loss of a man the photographer never knew, could never know, his absence making it possible (though who knows) for Lew to be here in the first place. Forking paths and multiverses, they’re in the air, imbuing our traumas and silences with the infinite weight of context—not just the past, present, and future but the what if. Yet if conveying such weight is a maximalist project, Lew’s portraits interest me because they’re deliberately uncluttered.

Still figures are neatly framed between window shutters, an open car door, shadows, light. In the restaurant, plastic tulips take the spotlight next to a Michigan Chinese mainstay, almond boneless chicken. At home, Lew’s now retired father sits in his socks and his old work uniform. One can draw a straight line from the lamp in the background, to the United States Postal Service logo, to the floor vase in the foreground—the symbol of an American institution floating between two objects that could have been acquired by googling “oriental decor.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Not so, Lew tells me. He grew up in this house, with that lamp and vase. After coming home from the post office, his father would sit at that ottoman to decompress and chat. Lew has his family reenact everyday rituals, from the trimming of flowers to his mother slipping food to his brother before he drives off. There’s a private intimacy here, from which the photographs also provoke a more public meaning. The lamp, the vase, the logo, the father, the socks—are the relationships among these elements complementary? Contradictory? Depends who’s looking.

Set mid-meal, mid-chat, some of the images also indicate an interruption. The subjects look back, as if aware of our looking. But these, too, are replicated scenes, the usual motion of spontaneity channeled into the stillness of control. To be aware of such control is to question the very connections that you can’t help but make.

“The connection I have for Vincent Chin was through the documentaries that I watched, based on so much pain. I can’t fully embed myself into that,” Lew explains. I question, too, the line that we feel compelled to draw from Chin to more recent incidents of violence toward Asians, from the Atlanta spa shootings, to the assaults on Asian elders, to the Monterey Park and Half Moon Bay shootings, committed by Asian male elders. As though a line would make all this tragedy more meaningful. As though there were such a thing as more meaningful.

Lew’s work resists this pressure: control is also a means to build a protective structure around the living. When posing for the camera, Lew’s mother felt, at first, as though she were playing a character; now she’s happy playing herself. Afterward, Lew shows her the pictures on his camera, a method of instant collaboration that was one of the reasons he switched to digital from his usual film. If these photographs obscure a larger context, they do so as an act of care. I think of Grace Paley’s short story “A Conversation with My Father,” in which a writer tells her dying father different versions of a sad tale, to mixed results. “How long will it be?” he finally asks her. “Tragedy! You too. When will you look it in the face?”

The story ends on that question. But perhaps Lew’s portraits pick up the thread. Look or don’t look, they say. I’ll listen all the same.

All photographs from the series In Between You and Your Shadow (2021–ongoing). Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.” Jarod Lew’s photographs are a continuation of his commission for Creating Stories for Tomorrow, a series produced in partnership with FUJIFILM.