Featured

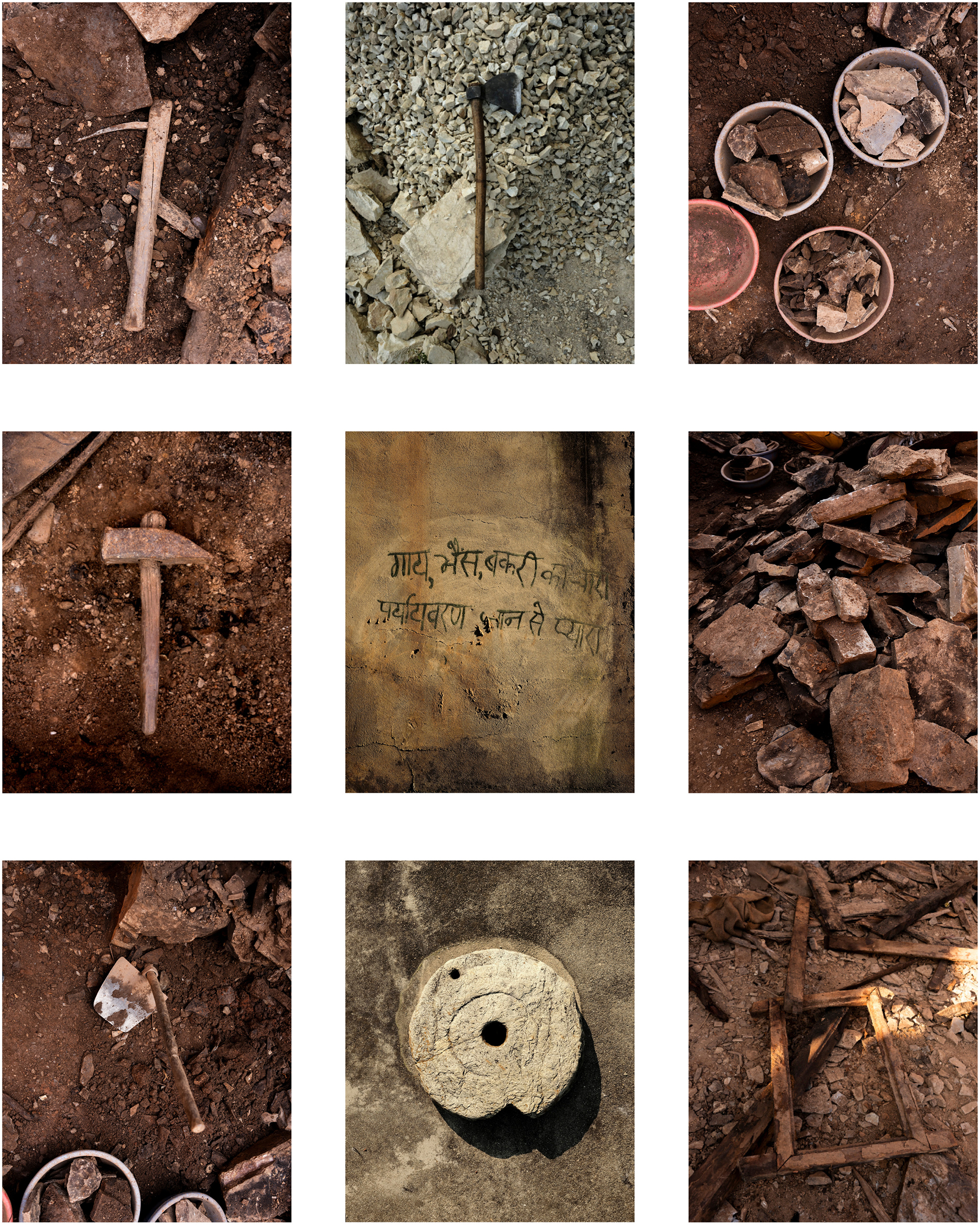

Ashish Shah’s Languorous Portrait of the Indian Countryside

Known for his distinctive work in fashion photography, Shah grew up in Uttarakhand, a state where many are leaving for the city. What would it mean to return home?

Uttarakhand is haunted by the ghost of migration. The north Indian state, which borders Nepal, harbors the source of the Ganga River, which is worshipped as a goddess. As the legend goes, Ganga migrated from the heavens to bring salvation to the accursed ancestors of Bhagiratha, the Ikshvaku king after whom she is also named Bhagirathi. Then there are the annual winter migrations of deities to their temporary shelters downhill, which residents mark with music and fanfare.

Lately, however, the state has been grappling with migrations of a different nature that have left vast swaths in districts such as Pauri Garhwal, Tehri Garhwal, and Almora abandoned. According to a 2018 report by the state’s Rural Development and Migration Commission, 734 villages became depopulated between 2011 and 2018, raising the total number of “ghost villages” in Uttarakhand to 1,768. Lack of employment opportunities, road connectivity, and education and health infrastructure are the primary reasons behind the exodus. Unlike the seasonal influx of wage laborers from the neighboring states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the outgoing migrants from Uttarakhand can secure more permanent tenures by virtue of being better educated. Not surprisingly, Pauri Garhwal, the district with the highest literacy rate, is also the most deserted.

In 2022, Ashish Shah, a migrant from Uttarakhand’s capital, Dehradun, who has carved himself a niche in Indian fashion photography, returned to his home state to capture life in the ghost villages in Pauri Garhwal. “I was born and grew up in these territories until my early twenties,” Shah said recently. “I am very much a part of the same shift.”

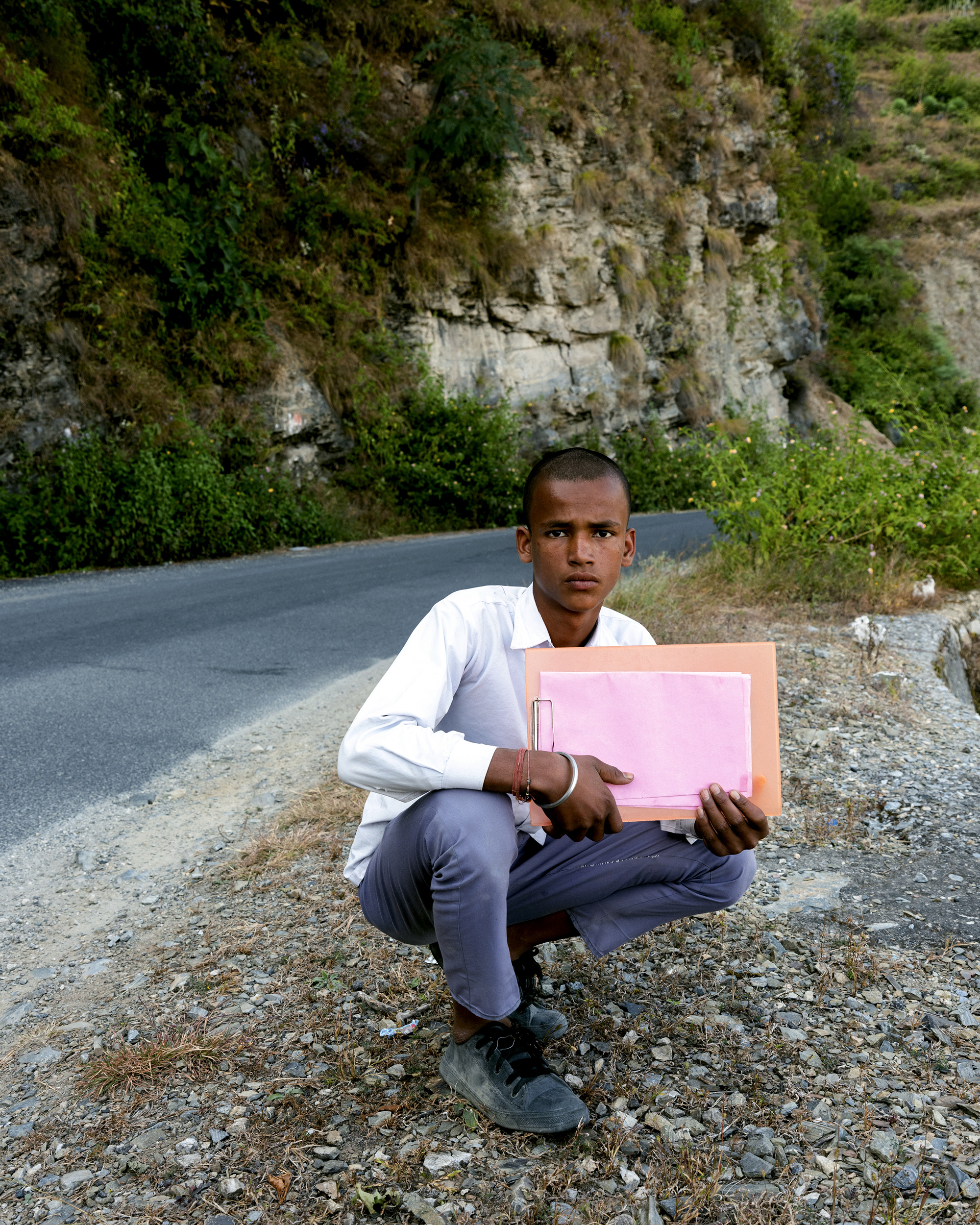

A sense of dereliction and waiting consumes his new series The Last Inhabitants of Pauri (2022). It lingers in doors long-locked, in unused charpoys and buckets, in overgrown houses, and, most of all, in the attitudes adopted by the remnant inhabitants. A sari-clad woman looks on morosely in the wake of her son’s departure for a job somewhere in the plains; the moment seems frozen beyond photographic time. Two women appear amid the drawn-out sigh punctuating a habitual conversation that breaks the routine of chores. Fingers twined and hunched slightly, the woman in pink conveys resignation, while the gaze of her companion interrogates the unexpected presence of the photographer-stranger. Framing her henna-dyed and braided profile is the creeping halo of bottle gourds, which will end up as precious weights in the jholas (cloth bags) of husband, brothers, and sons reporting back from holiday.

Ashish Shah, Women chatting, Sheela Village, 2022

“Often fashion imagery in India is very alienated from the world it represents,” he says. Commissioned by brands such as Alexander McQueen, Byredo, and Raw Mango, Shah has managed to successfully challenge the prevailing Western conventions that pertain not only to casting but also the choice of setting, framing, and bodily comportment.

While investigating the demographic shifts bedeviling these villages, Shah remains wary of the trap of victimizing narratives. He is conscious about not letting his representations of Garhwali country life and its challenges slide into value judgements about this lifestyle. Occupying the yonder side of migration, Shah recognizes the luxury of playing gully cricket in the middle of the day and indulging in unhurried conversation, to say nothing of the health benefits of daily exercise as well as the consumption of unadulterated food and air. His depictions of backbreaking labor are unfailingly relieved by moments of languor.

There is an image of a man hauling a gas cylinder, and one of an apple farmer who returned to the village, where he started a polyhouse, a type of greenhouse for sustainable horticulture. “While I came across many villages where the young ones have moved out in search of a different life, Lakhpati Prasad, my local guide, moved back to his village to take care of the ancestral land, striving for a balance in the ecosystem, against the will of his wife and kids who still live in the city,” Shah explains. Elsewhere, one witnesses a house being rebuilt, one of the many to get a new lease on life during the pandemic, which drove migrants out of work and back to their villages. A few have stayed to set up small businesses and are reinventing their former lives with insights gained in cities. In this way, Shah’s series presents two sides of the migrant coin as it settles in the state of Uttarakhand.

Ashish Shah’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera.

All photographs from the series The Last Inhabitants of Pauri, 2022, for Aperture