Interviews

Danny Lyon on the Making of “The Bikeriders”

Lyon’s riveting book about a Chicago motorcycle club is one of the definitive accounts of American counterculture—and the inspiration for a new film starring Austin Butler and Jodie Comer.

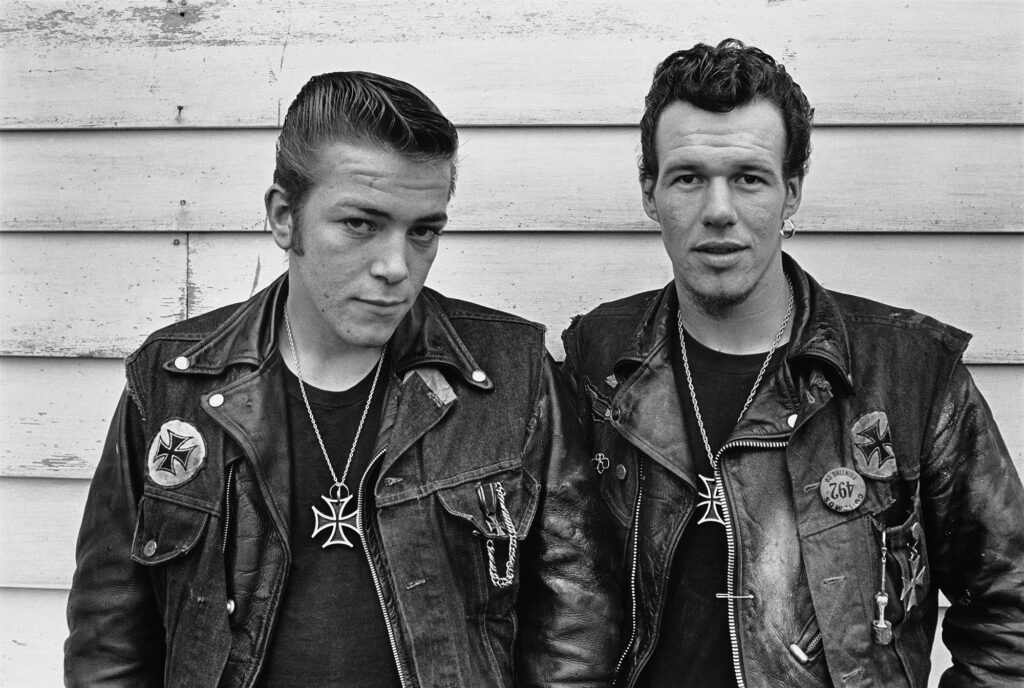

Danny Lyon has a story to tell—many stories, in fact. The photographer who captured a young John Lewis, then chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other moments of the early civil rights era is known for embedding himself in communities and documenting scenes with historic import and cultural specificity, including a 1960s Texas prison, a downtown New York demolition, and the Vietnam War protests. Perhaps most famously of all, Lyon photographed the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, joining the group to document it from the inside. But to say this was simply the strategic move of an artist is to elide the complex ways in which Lyon has always tended to live his work.

On the eve of his forthcoming memoir, This is My Life I’m Talking About (2024), where he tells all the best stories of his eighty years, Lyon spoke about his landmark work The Bikeriders, first published in 1968 and reissued by Aperture in 2014, and inspiration behind a new Jeff Nichols film starring Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, and Jodie Comer—and Mike Faist as Lyon—releasing this month.

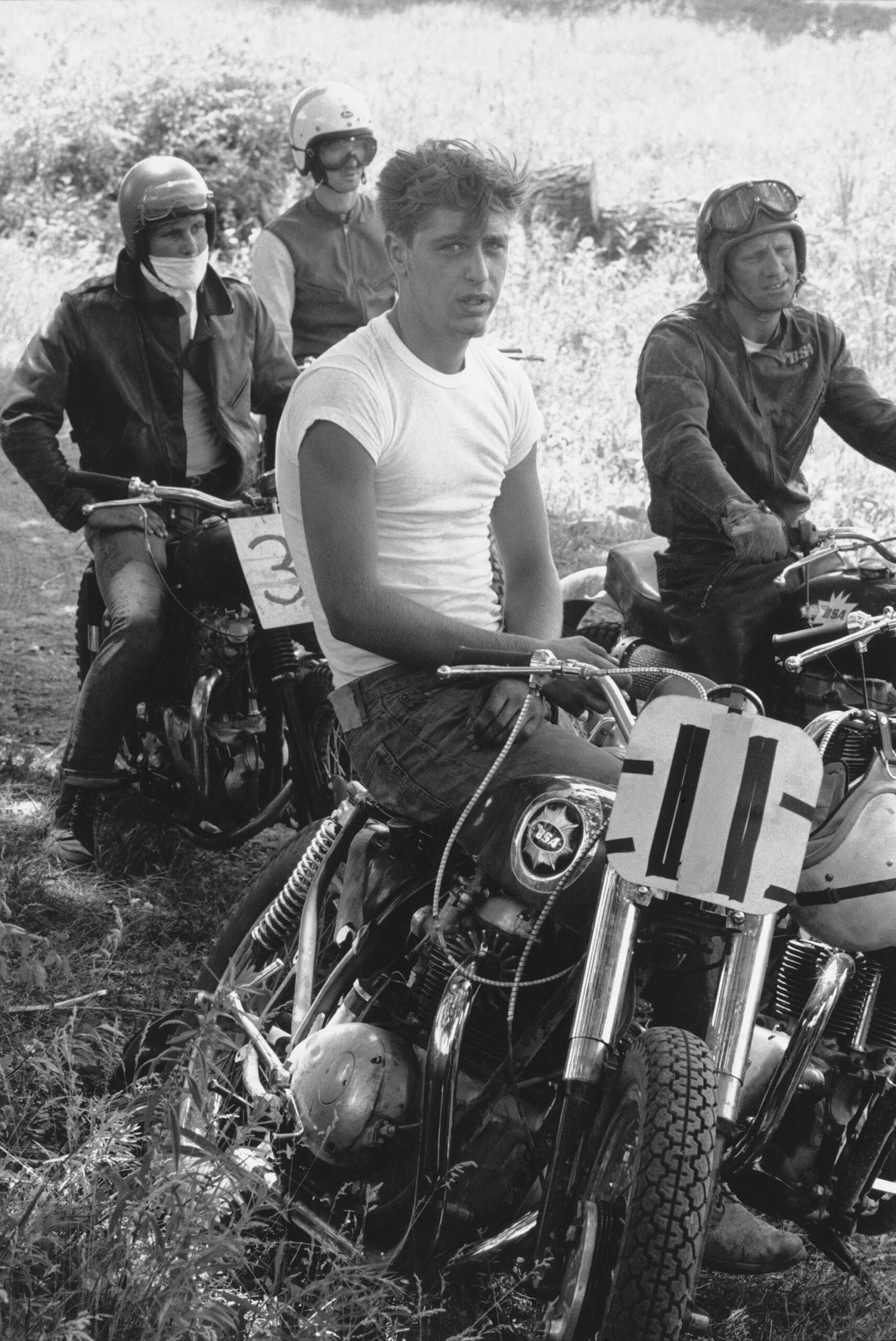

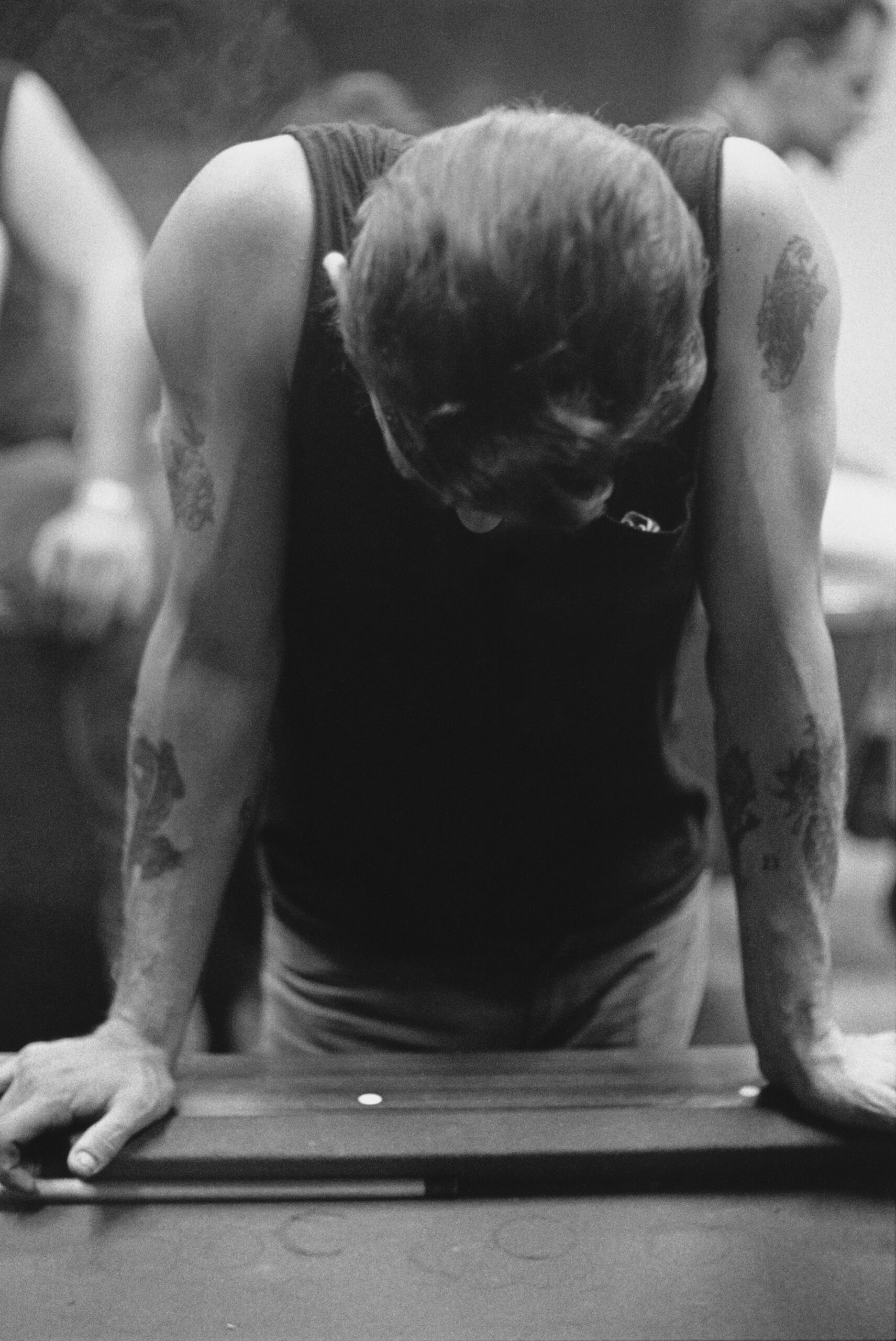

“I met Andy at the bar across the street, leaning on the juke box,” Lyon writes in the memoir. “He looked a little like a short James Dean, his hair as curly as mine. Wearing a sleeveless shirt, Andy was lame, and staggered badly with each step he took. He limped over and grabbed a man that Jack had posed with, pressed his cheek against his face, and wanted me to make a picture of that as his buddy held out the bottle of beer. By my second exposure, Andy had completely embraced his friend, his body wrapped around him, without disturbing the beer, which everyone insisted be in the picture. We went outside to stand in the doorway where Andy posed with a pretty dark-haired girl wearing a leather vest. Sometime that same night, somebody said to me, ‘Why don’t you join the club?’ I had found my subject.”

Here, Lyon speaks about his first race, why he doesn’t like the term photobook, and the desire to drive off into the sunset. This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Lucy McKeon: Tell me a little about your introduction to this world that would become your work titled The Bikeriders.

Danny Lyon: Some of the first pictures I ever made are of motorcycles. This is years ago. I’m young. I have my first good camera, which is this East German–made single-lens reflex called an Exa. I’m a student in Chicago, and I have friends who are riding motorcycles. The very first picture on the first page of The Bikeriders is a portrait of a very handsome guy. He was from upstate New York, a University of Chicago student. His name was Frank Jenner. He had entered school, and he had been a motorcycle racer—this was as an eighteen-year-old. He’s part of our crowd, and we all look up to him, and we all want to get motorcycles. That’s the first picture in the book because it’s really through Frank that I enter this world. BSAs were popular, which I think are British, and I rode a Triumph, which is also British. Nobody rode Harley-Davidsons. I was looking at the Chicago Outlaw website, and it’s a requirement today, if you’re a member of the Chicago Outlaws, to ride a Harley-Davidson. None of us did.

McKeon: So you didn’t grow up with this culture in Queens, I’m imagining.

Lyon: I couldn’t even drive a car in Queens.

In 1963, I had a good friend named Skip Richheimer, who is a graduate student at that point. But by then, I’m close to my junior or senior year. We’re both bikeriders, and we get in his Volkswagen to go to a race. He was also a photographer, and he’s still alive. We drive off to Wisconsin to a rally. Many years later, I met Bob Dylan, who also rode a motorcycle, apparently almost got killed on one. He had seen the book, and he used to go to the same track. It was McHenry . . . or where the hell was it? I think I got it right. Let’s call it McHenry.

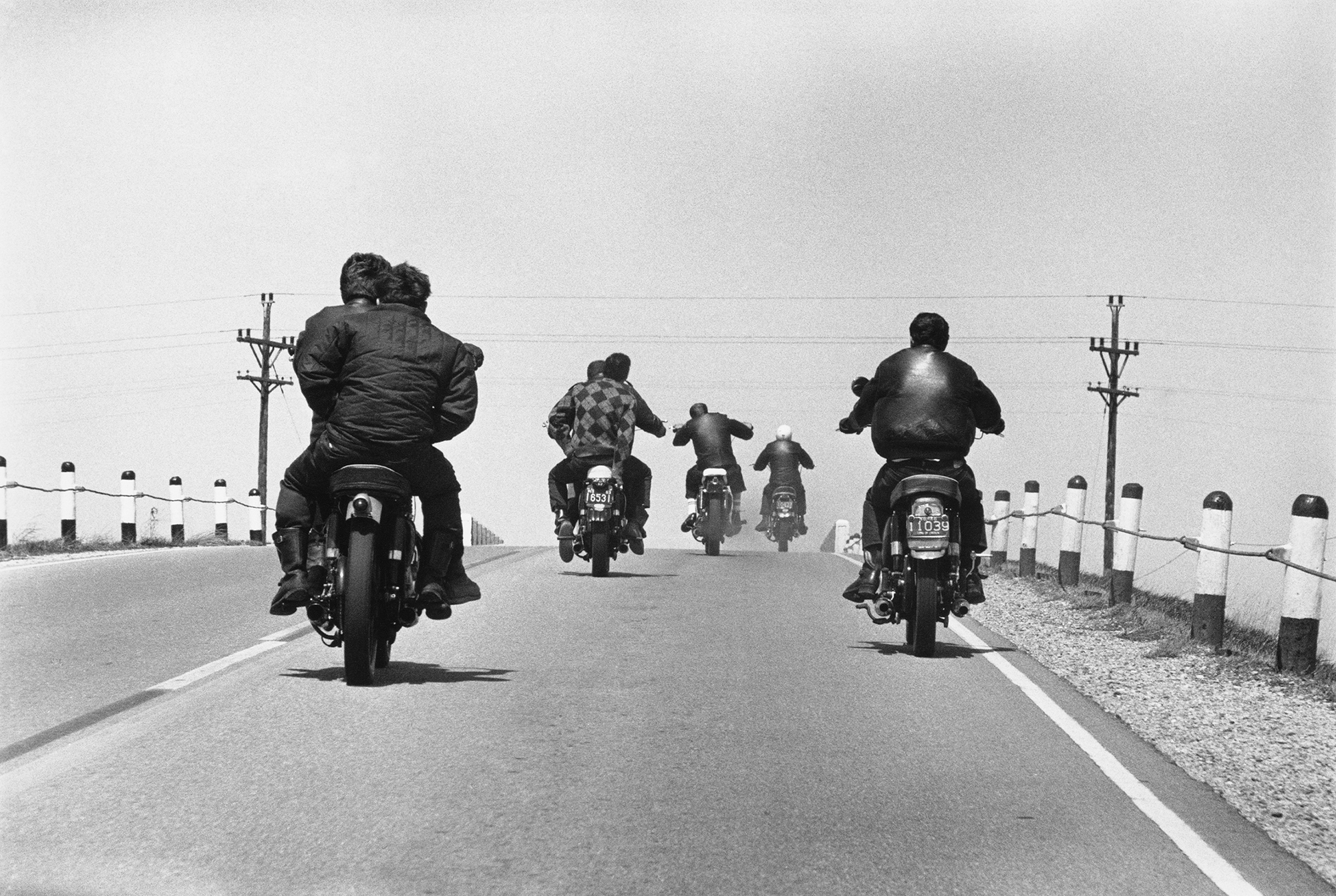

But I was in Wisconsin when these motorcycles pass us—I see them behind us, and Skip’s driving, and I start yelling, “Keep up with them!” I’m shooting through the front window with a 105mm lens, and I make this picture called Route 12, Wisconsin, which I think the British Museum later declared as a masterpiece of photography. I was twenty years old. It’s a pretty good picture. It’s perfectly arranged. It’s done through the front window of a moving car, and it’s very geometrical. That’s the cover of The Bikeriders.

The Bikeriders

40.00

$40.00Add to cart

McKeon: Can you remember your impression of that race with Skip? Was there a sort of epiphany you had about bikeriders and photography?

Lyon: Epiphany. I love this. I’m going to try to invent one for you. It wasn’t really like that. The day was great. But did I end the day saying, I want to do bike rides? No. The light was apparently perfect, meaning it was a bright, overcast day. But I think it was being around and seeing these guys.

I shot a bunch of film, and I was all excited, and I showed them to Hugh Edwards at the Art Institute of Chicago. Hugh had the epiphany. He said this stuff’s incredible. He told me I should make a book about it. He wrote me a letter about it. I got the letter in May 1963. The letter was a result of looking at the pictures I made that bright, overcast day, and he mentioned the idea of a book, suggested all these crazy people who could write the text. I think he mentioned John Dos Passos, James Jones, and somebody else [Burroughs]. And he told me it should be in gravure. He had it all worked out.

Then, I got caught up with the civil rights movement. But I never forgot my time taking pictures of motorcycles, so I returned to Chicago, two years later.

McKeon: Two years later. So in 1965?

Lyon: 1965, I return. At that point in my life, I’m already a photographer. I’ve also gotten better because I’ve been trying to get better. I was a street photographer in New Orleans, and once in Chicago, I go to Uptown, and I start doing better work. But I was still looking for a subject. I think I knew I wanted to do a book, and the model for me was Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which is mostly text. I read the whole thing, and James Agee’s writing really spoke to me. The Americans had been a big flop, but it showed anyone paying attention that the way to be recognized as a photographer was to make a book. So to make a book was my big dream—and I did.

But the book was a total failure. Not only was it a failure but the printing was also horrific: Seven pictures were out of register; there was no ink on it. There weren’t any typos, but as for reproductions, they were awful. It broke my heart when I saw it. And in addition, it was a total flop. That’s the first edition. It came out in 1968.

Twenty years later, Jack Woody, who’s a wonderful publisher, wants to do it in gravure, and he makes it a little bigger. There are no additional pictures, but the format’s a little different, and I write a second introduction. So that’s the second edition. That’s really gorgeous.

But The Bikeriders was meant to be a popular book. It was originally in softback. You could fold it in half. You could fit it in the back pocket of a pair of jeans. It cost $2.95. In other words, it wasn’t meant to be an art book. It was meant to be a book that was based on photographs and had text and was affordable. So, with the second edition, it lost the feel, so that upset me.

Then, in another ten years, Chronicle Books offered me money to publish it again if I added pictures. This is the worst version of The Bikeriders. I added color pictures in the back, because I had made color pictures. I wrote a third introduction. And I really hated that book.

Life went on, then the people at Aperture, including Lesley A. Martin, asked if they could give it try. And this time, they did it right. It’s great. I love the new edition.

McKeon: A success story. Tell me more about the text in the book. You used a tape recorder when you were making it.

Lyon: So I’m making these photos. I found my subject. It’s a fabulous subject, and it’s perfect for photography and I know it. I’m cranking out all these pictures. I joined the Outlaws club. I have access to all these other guys, and I’m also protected by them, meaning I can wander in bars or at rallies, and I’m wearing a patch, so no one’s going to fuck with me. I’m one of the guys, and I make the pictures.

I go to New York, trying to publish it. Everybody was saying no to me. I go to Aaron Asher. He was at Viking and did these arty photography books. I remember sitting in an office with him. I had these boxes of pictures, and he told me this is just a box of pictures and that it’s not a book. He said I needed a text. I go back to Chicago. I got help from Lucy Montgomery, who had been a big supporter of SNCC. She was a white Southerner of wealth. I said, “Lucy, I need a tape recorder.” I needed a portable one because I rode around on my motorcycle. She gave me eight hundred dollars, and I bought a small Uher five-inch reel-to-reel tape recorder. I recorded everyone, and I made my text.

It turns out, when I got it published, The Bikeriders was the second book in the English language to use a tape recorder as a source of the text. I had the recordings typed out by a woman who worked for Studs Terkel. I picked parts of the text. I did very little editing. I simply cherrypicked the great speeches, made that the text—and then no one would publish it. In fact, I went to Michael Hoffman at Aperture. But they wouldn’t pay me any money, and I was determined to live off my work. So I said no. Then, I ran into Alan Rinzler, who I knew from the civil rights movement. We had had a big fight, and I ran into him by accident. He was at MacMillan, and he did, like, fifty books a year—trade books. He slipped the contract for my book into his pile, and it came back approved.

It’s amazing to sit in a movie theater and watch Tom Hardy and Austin Butler and Jodie Comer speak the lines that I recorded in 1966.

McKeon: There’s a wonderful scene in your forthcoming memoir about a 1966 gallery show, speaking of Hugh Edwards, who put it up at the Art Institute of Chicago. You talk about inviting the bikeriders and their families to come see the photos displayed.

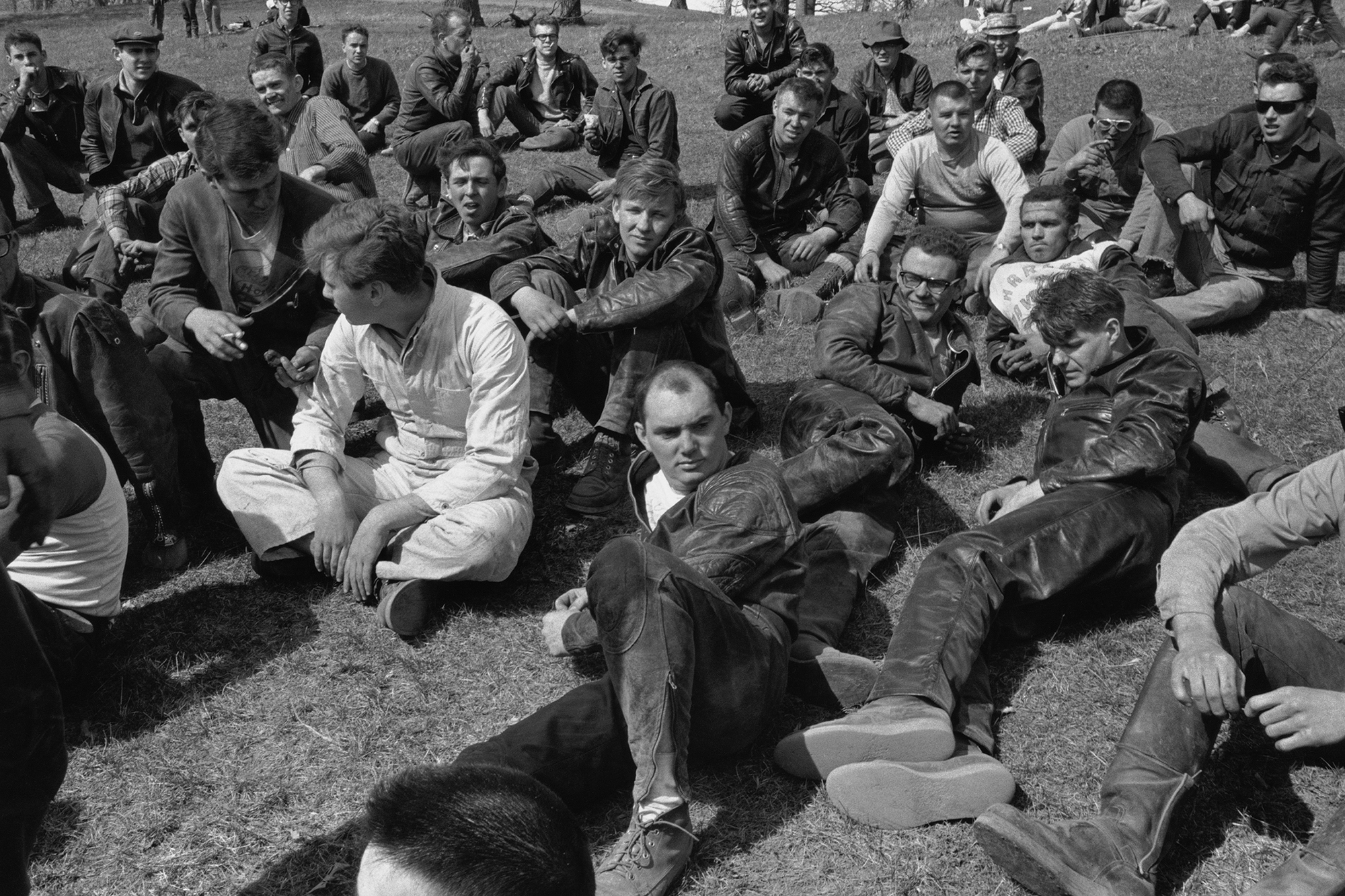

Lyon: Hugh was the curator. He’s really an enormous figure in photography, really the greatest figure in the museum and curatorial worlds of the late twentieth century. I believe John Szarkowski said so when he visited the Art Institute. Hugh was a self-educated guy from Paducah, Kentucky, who loved The Bikeriders. He gave me my first show (I was twenty-five), and he showed The Bikeriders, and I think he showed prints of Uptown, Chicago (1965). I was in the Outlaws club at the time, and the whole gang came down. I have pictures of them. They got dressed up. I have one frame of them in the room: their children are in it, the women dressed up. Most of these guys never went downtown. Some of them were truck drivers. They were blue-collar people. About twenty-five of them came, and I took pictures of them in the gallery.

But the club changed. I left and then it changed. In the third edition of the book, I wrote about the change. The change happened when Vietnam vets, who were into drugs and were violent, took over the club. This didn’t happen when I was present. So the Outlaws morphed, got indicted in a RICO charge. They got into a fight with the Hells Angels. It got really grim. This is public knowledge. And to this day, the Outlaws still exist. I was talking recently to a club member. They have thousands of members. This fellow, who’s a nice guy and retired from the club, said that some people joined the club because of my photographs. Which is funny. But I created this romantic vision of being a motorcycle rider. And then there were the people I knew—one of them was an electrician; the head of the club was a long-haul truck driver; Cal was a house painter who didn’t do anything; Funny Sonny played blues.

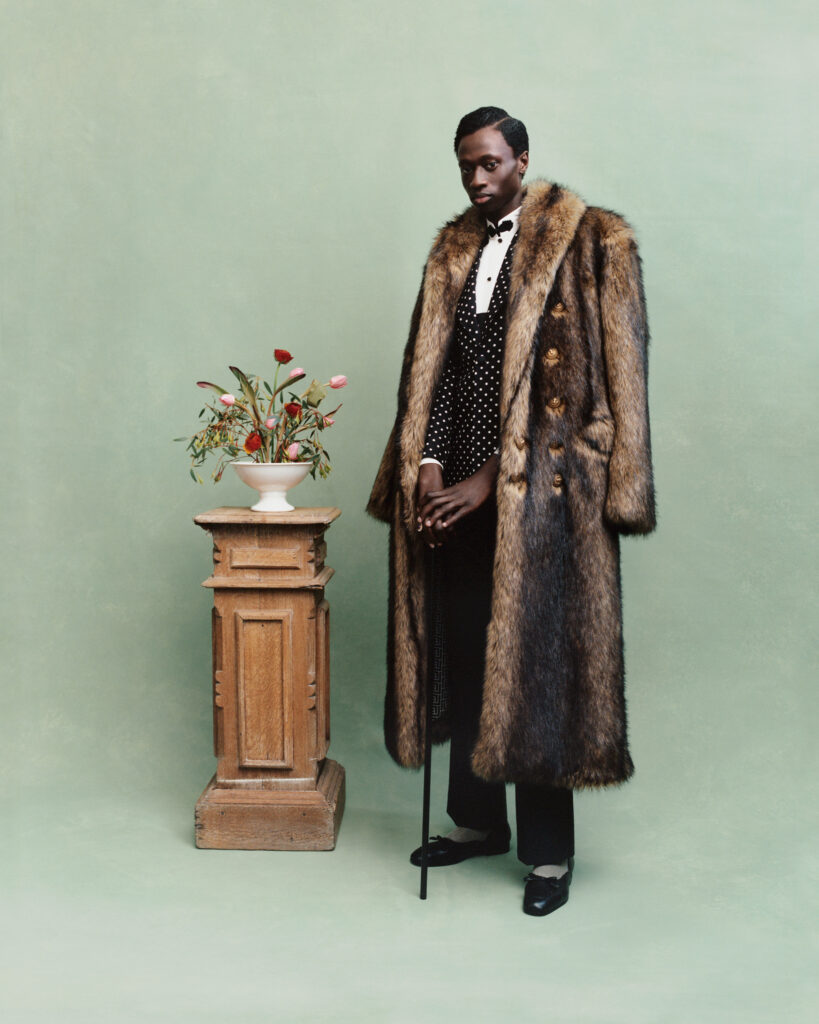

Courtesy Kyle Kaplan/Focus Features

McKeon: What do you think of the movie version of The Bikeriders?

Lyon: Well, Jeff Nichols made the movie. Years ago, he told me he wanted to make a movie out of my book. I’m thinking, Wow, movies are a big deal. The analog recordings I made survive. You can hear them on my blog, Bleak Beauty. You can click on them, and you can hear their voices. They’re on quarter-inch tapes. About thirty or forty tapes survive, most of which I never even used. So I gave all of it over to Jeff.

Jodie Comer, the actress who plays Kathy, and Boyd Holbrook, the actor who plays Cal, could sit down with earphones and listen to these recordings, and so as actors, they do perfect imitations of Kathy’s and Cal’s voices. While not an Outlaw, Kathy’s a woman with three children who’s married to this kind of young lunatic and who also narrates a number of stories in the book. And Cal, who is a Hells Angel, narrates another four. Zipco was an amazing guy and tells an amazing story in the book about the draft board. He’s incredibly funny, like Falstaff. I mean, he’s a drunk. He’s a fuckup. He has a Latvian accent. He’s very, very, very funny, this guy. When I interviewed him, he’d gotten drunk, crashed his bike, broke his leg, and Cal and I visited him in the hospital—and that was one of the recordings.

Anyway, these are the stories that drive the film, and it’s amazing to sit in a movie theater and watch Tom Hardy and Austin Butler and Jodie Comer speak the lines that I, as a twenty-five-year-old kid, recorded with an analog tape recorder in 1966. They’re the exact same words.

McKeon: You consulted for the movie, right? Did you visit set?

Lyon: They were filming in a small town outside of Cincinnati, a place that hasn’t changed much since the ’50s. On a street corner was a bar, and when I stepped inside, it looked exactly like my pictures of the bar sixty years ago, only it was in color. I was transported back to my youth. Outside, parked all around the bar were vintage motorcycles, mostly Harleys along with one BSA and on the corner, a Triumph. It was the very same bike I had first ridden, the 440-pound single carburetor TR6, with a worn banana seat. I went over and sat on it. Mine had a black gas tank, and this was dark brown, but otherwise it was exactly the same. And as I looked down next to the flat oil tank, I saw the key, a very small key stuck into the bike, and I reached down and turned it on. Then, I jumped up in the air and came down as best I could with my right foot on the kick-starter, and the motor sort of coughed. I jumped down again, and the bike roared to life. It was like the start of war, considering the amount of noise made from the straight pipes.

A hundred people were wandering around the set, setting up lights, and talking on radios, and every one of them turned to look at me. How badly I wanted to ride off on that bike. I was twisting the throttle in my right hand, making the engine roar, and all I had to do was push down with my foot and put it into gear, lean forward to knock it off the kickstand, and I would be riding that bike—my old bike—off into the night. I just didn’t have the guts to do it.

McKeon: Plenty of rides to recall in your past. You’ve gone and written a memoir. Tell me about that process. What has it meant to you, and what you were trying to do with it?

Lyon: I’ve been writing for years. The memoir has been a struggle, and I’m so happy to get it out there. Like The Bikeriders, it had no one wanting to publish it. I couldn’t get an agent for it. But Damiani, an Italian publisher, who’s doing a lot of picture books—I think they’re doing something by Susan Meiselas—said they’d do it. I’m thrilled. It’s on press now.

This kind of writing began for two reasons. One, I was in New Zealand fishing. I mean, this was fifteen years ago. I thought what I did was so extraordinary. I was just trying to go fishing. But fishermen are really crazy. I mean, they really can be psychotic. I was going through the jungle, climbing trees and falling off cliffs, then crossing rivers, hoping to catch a two- or three-pound fish—which, of course, I don’t do. But later I thought, This is so crazy I should write about it. And I did. I wrote a long manuscript called “The Fisherman,” and it was really terrible. Then later, I had health problems. I started from scratch. And then, people like you helped me edit it, and now it’s done.

There’s a lot of adventure in being a photographer. When Nancy told our son Noah that I was writing a memoir, Noah said, “Again?” This is because Knave of Hearts (1999) is in fact an illustrated manuscript with a memoir within, but it’s much shorter. This new one has more writing, more words.

McKeon: Did this feel like a chance to tell a different story than you had before?

Lyon: To get even, you mean? I wish I had done that, but I didn’t. I’m eighty years old. The civil rights movement for me was sixty years ago. There are so many adventures involved in the kind of work I did.

Looking back on my life, I don’t know, maybe I did do a lot of it for the adventure. I get bored. I love doing exciting stuff. I seem to like danger involved. I even managed to make fishing dangerous.

I’m doing stuff now, and basically, I got to drive six hundred miles to do it. I love it.

McKeon: This is in New Mexico?

Lyon: Arizona. So far, I’ve done the Oklahoma Panhandle, Nebraska, and Arizona. We’re about to head to the California border. I don’t want to talk about it too much. I want to do it.

McKeon: Do you have a favorite picture from the book or a favorite speech?

Lyon: Well, I’m glad you asked. Because of this conversation, I decided to pick up the book. I looked through the Aperture edition of The Bikeriders, which is just beautifully reproduced. There are forty-nine pictures. When you’re a young photographer, you just want to make a great photograph. That’s all you want to do. I don’t know what painters do . . . they make sketches and they make a painting. But photography isn’t like that. You can go out and make twenty pictures in a day. You can make fifty pictures in a day. But you just want to make one good picture—one really good picture. That’s what you’re trying to do.

There are only six great pictures in The Bikeriders. Which is great for me. That’s what I was trying to do. The rest is filler. It’s about making a book and showing it to people. In the prison book, that was also my objective. The objective has always been to make great photographs and then construct a book around it using texts.

I wish photography books were more respected, you know, as literature. There’s something I call “Photo Literature,” which sounds pretentious, I know. But Nan Goldin does it. Larry Clark did it. Jim Goldberg does it. Susan Meiselas does it. They use words. They are photographers, but they make books, and they use words. It’s a really kind of a separate category of books, I think.

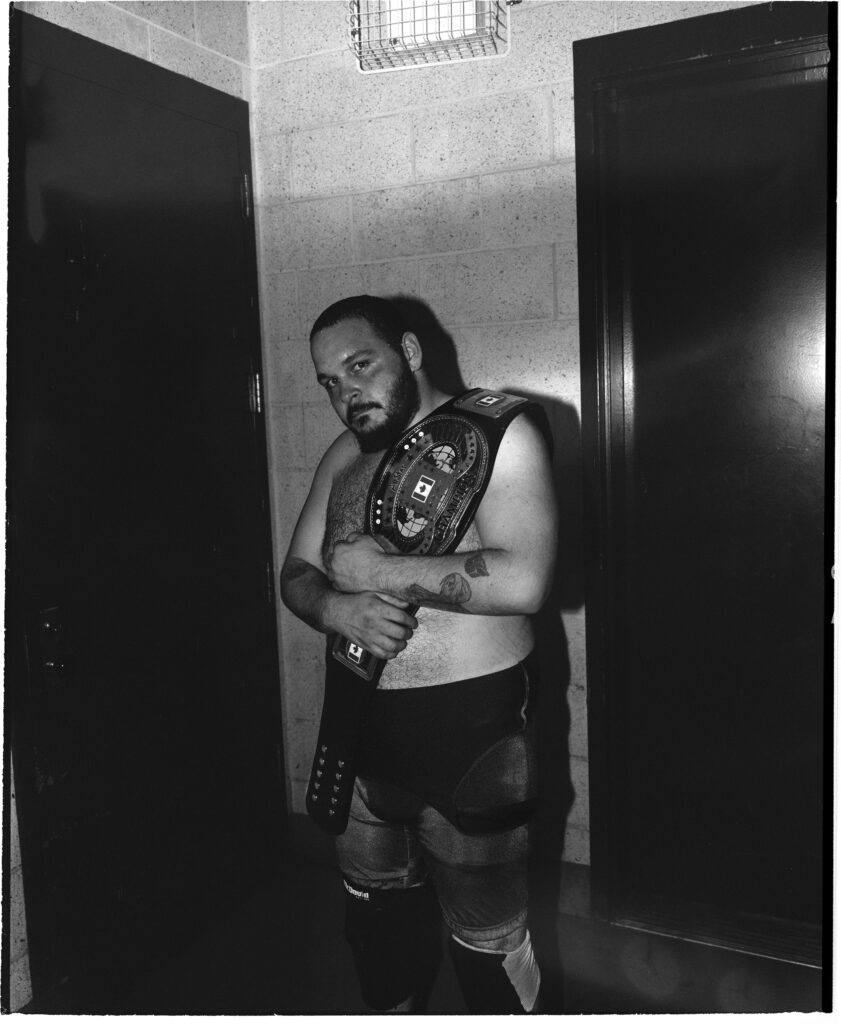

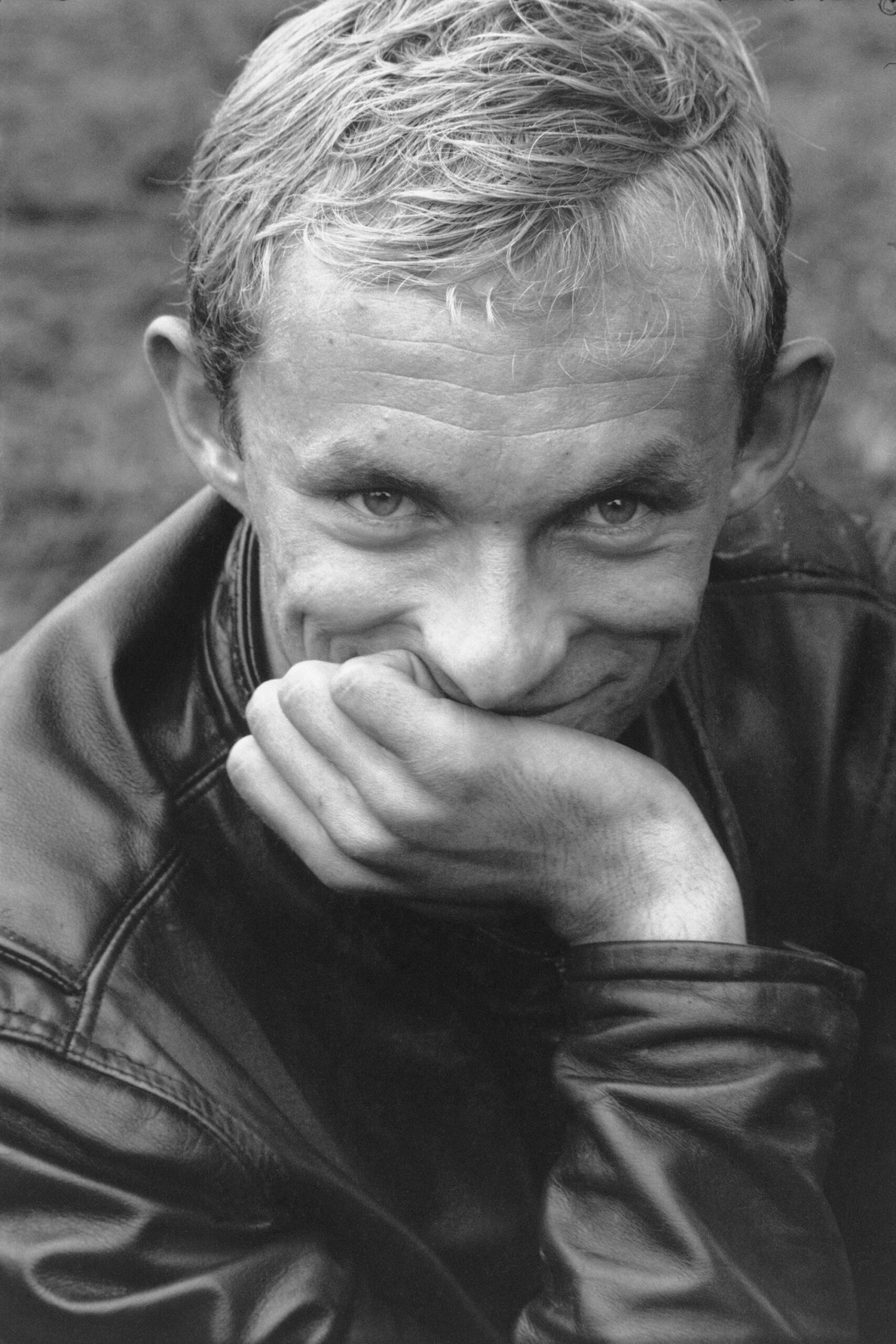

All photographs from The Bikeriders (Aperture, 2014). Courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

McKeon: You don’t like the term photobook.

Lyon: I don’t even like the word photography. I call photographs “pictures.” I did a book with Michael Hoffman, who was the head of Aperture, and he wanted to do a collection, which I resisted because it wasn’t really a book. It was a collection that’s called Pictures from the New World. Michael told me that Aperture spent thirty years trying to educate people about photographs, and now I want to call them “pictures.”

Photography was not considered an art. Stieglitz spent a lot of time saying photography is really an art form. Robert and Mary Frank were a couple, and Mary was an artist, and Robert comes to America in the late ’40s, makes his pictures in the ’50s, and he knows all these artists. He said he wasn’t considered an artist. His wife was considered an artist because she did sculpture. But Robert wasn’t. Hugh Edwards said there were only three types of photographs—landscapes, portraits, and interiors. Think about that.

McKeon: Before we close, I just want to return to your early experiences riding a motorcycle. I would love it if you would describe the memory of a ride, what that feeling gave you.

Lyon: When I was in Lower Manhattan, I would ride around on a red Triumph. People would come to New York, I’d put them on the back of my Triumph, and then I’d get on the East Side Drive, which skirts the East River, and going south, you go under all three bridges—you go under the Brooklyn, Williamsburg, and Manhattan Bridges on a motorcycle. There’s nothing but you, the air, and the water, and you can go around the bottom, come up the other side. It’s really a thrilling ride. There was less traffic then. No more. I got old. I like boating, and I had a tractor for a few years. All that goes. But I can still make pictures.

The Bikeriders was reissued by Aperture in 2014.