Interviews

Ed Templeton’s Delirious Skater Chronicle

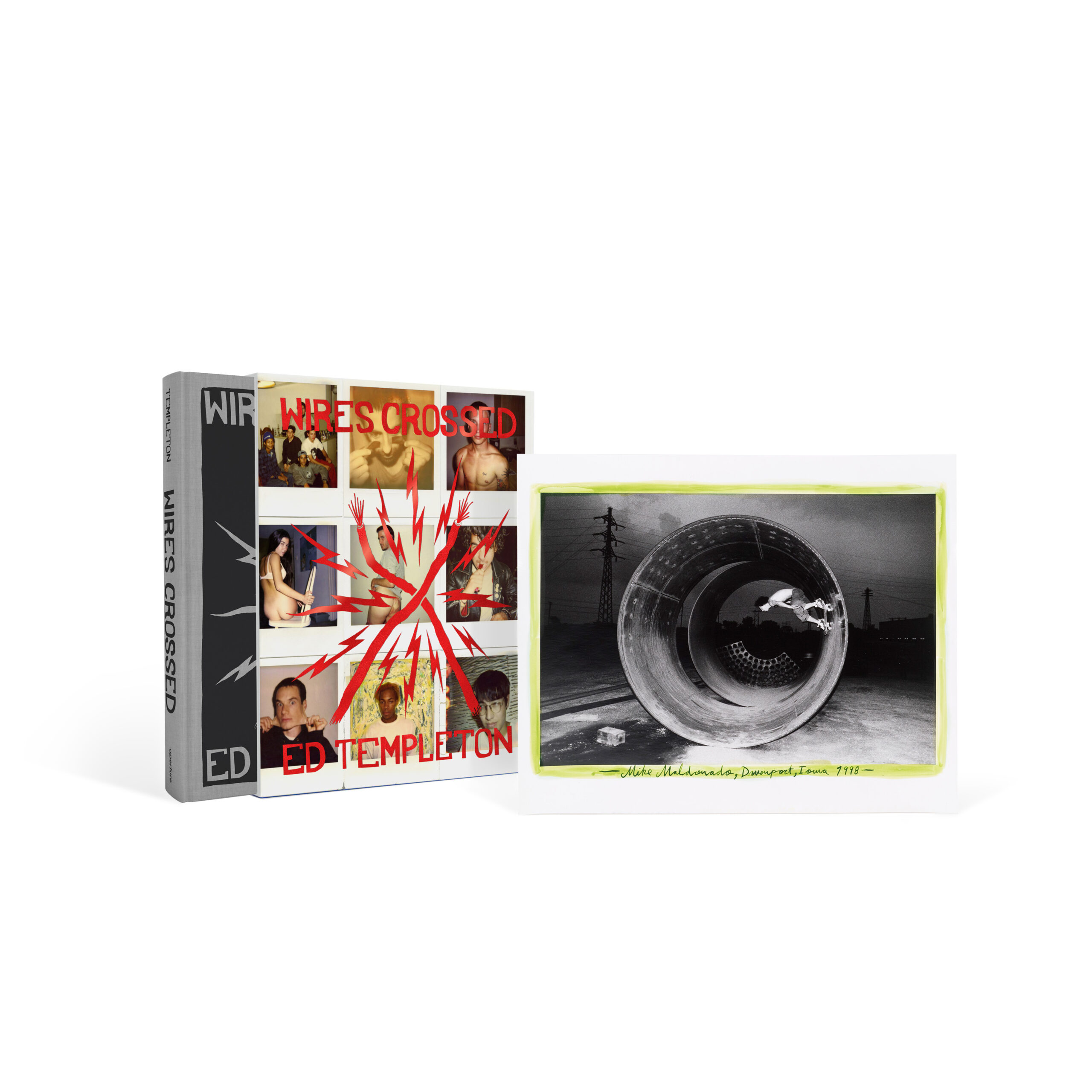

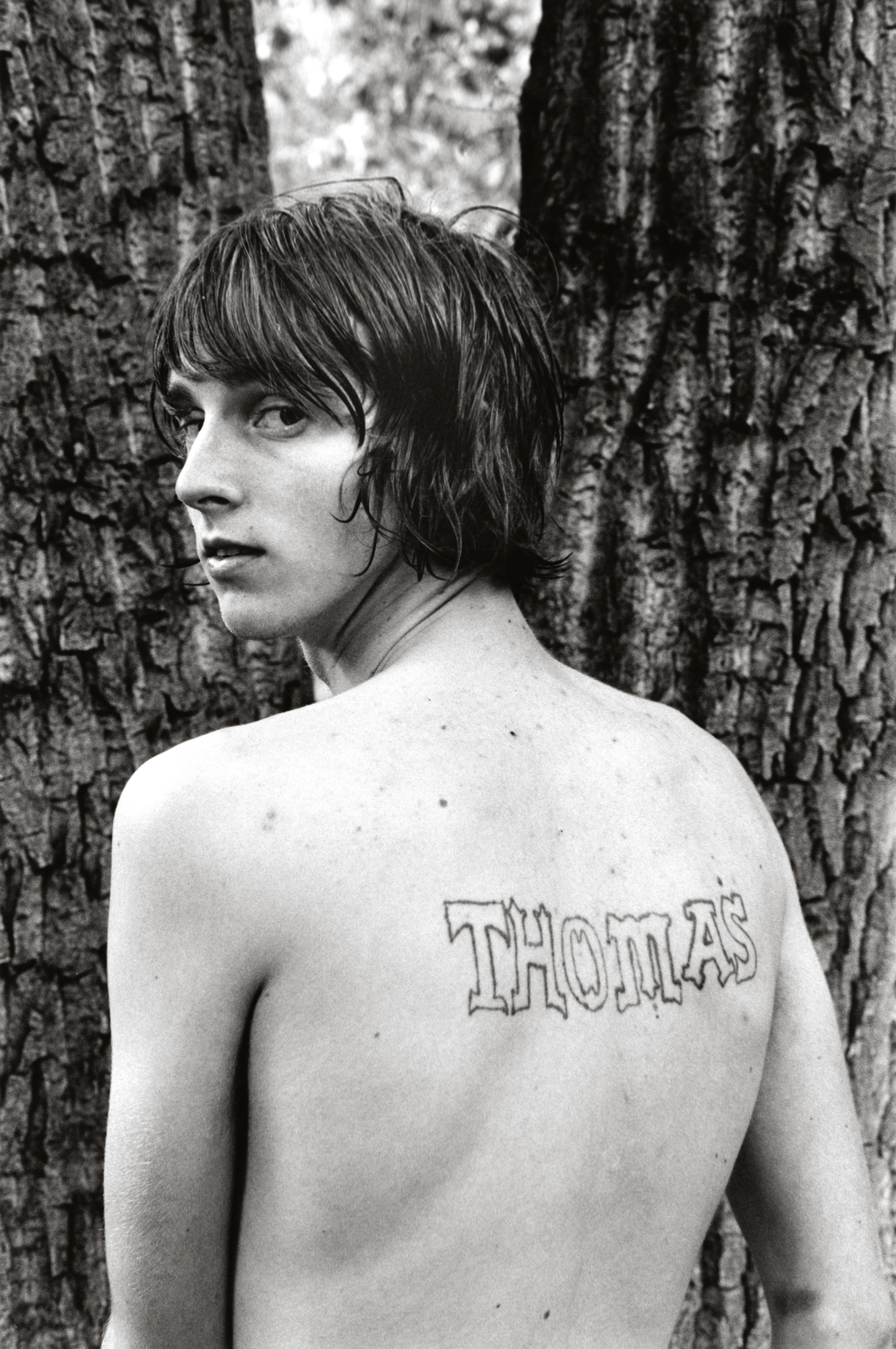

Part memoir, part document of a punk-infused scene, Templeton’s recent book explores the lives of skateboarders crisscrossing the world in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Ed Templeton occupies the rare position of having been a professional skateboarder and two-time World Skateboarding champion, as well as a photographer and artist working within the skateboard community as it gained increasing cultural currency in the 1990s and beyond.

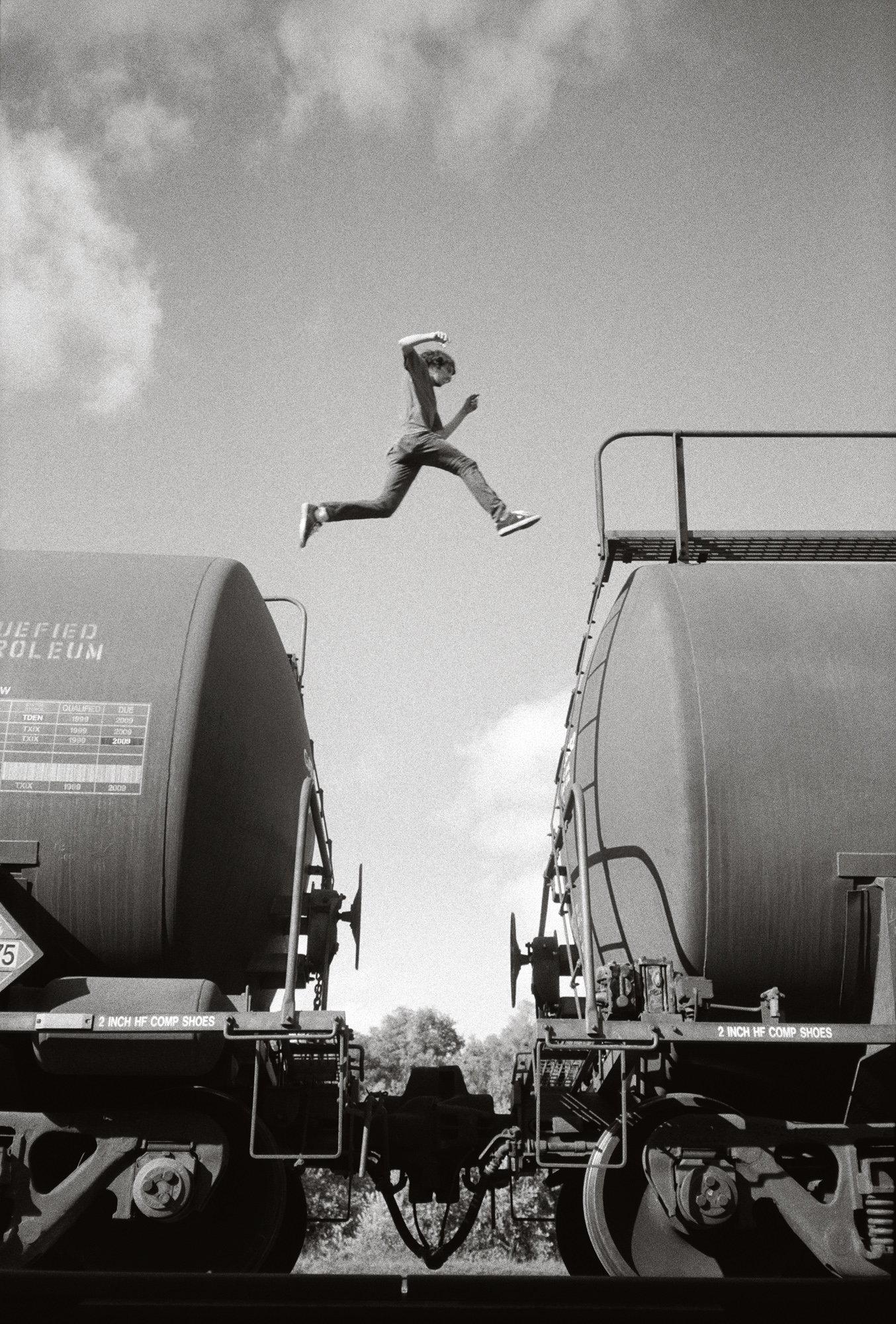

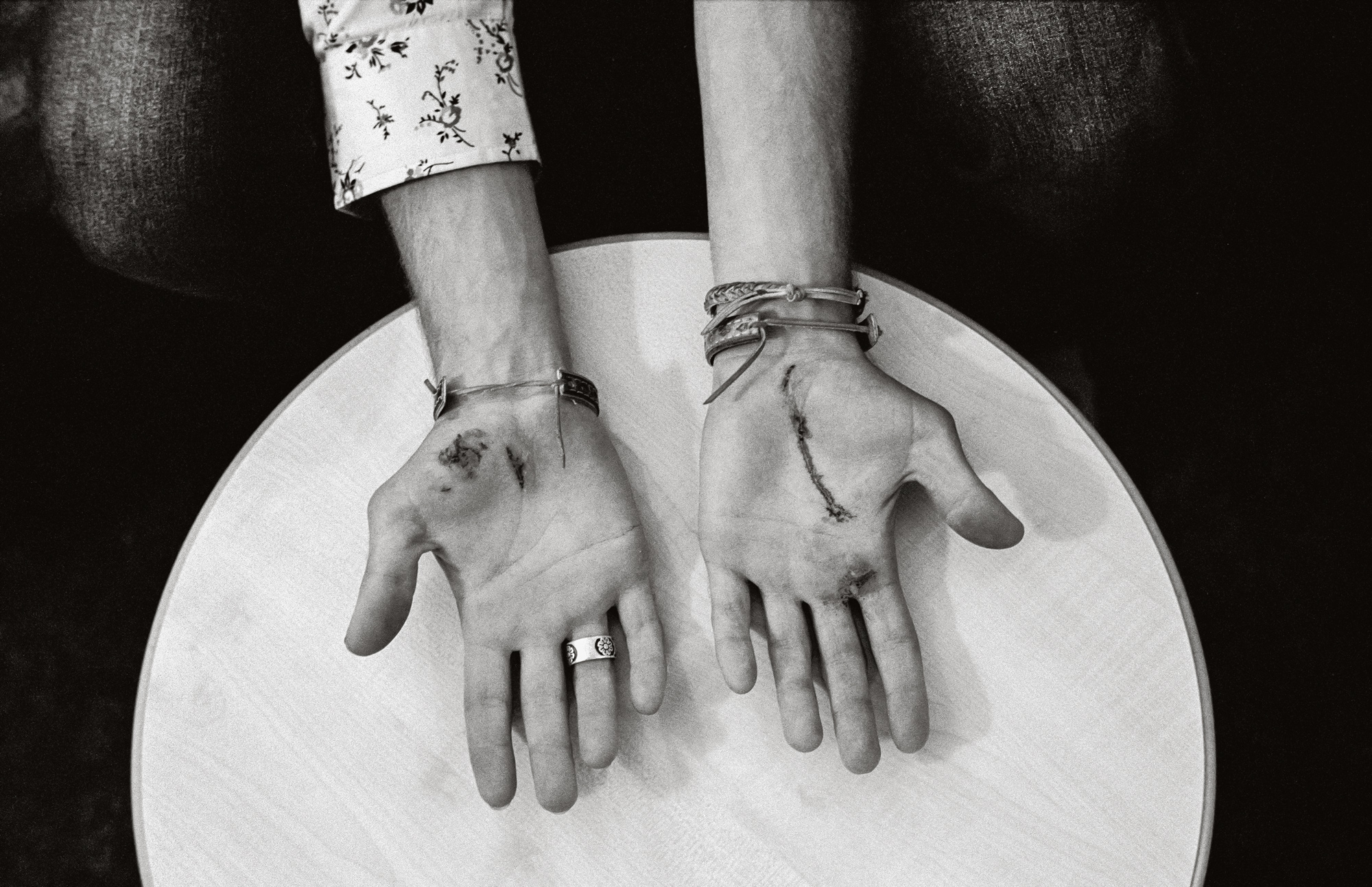

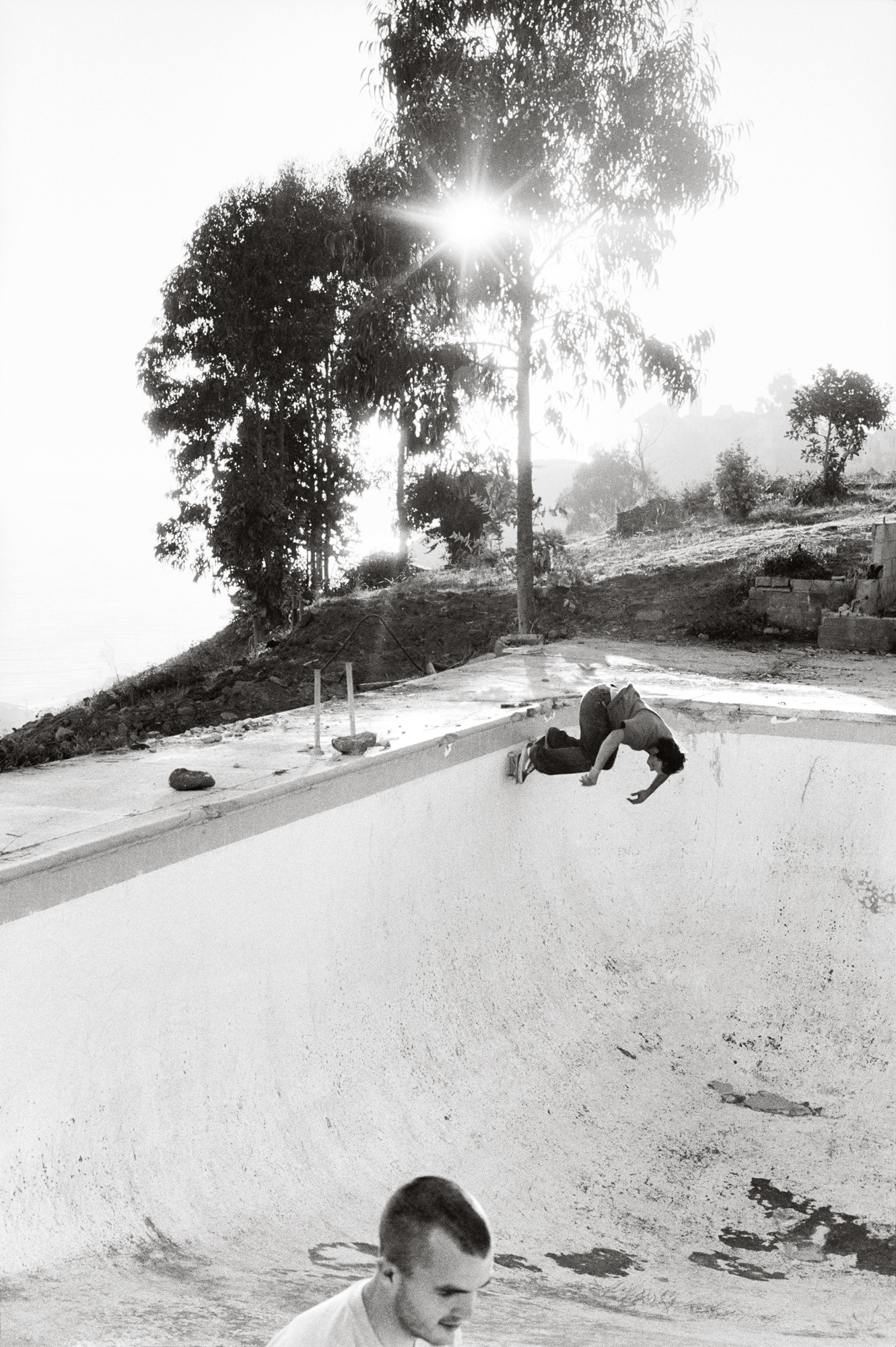

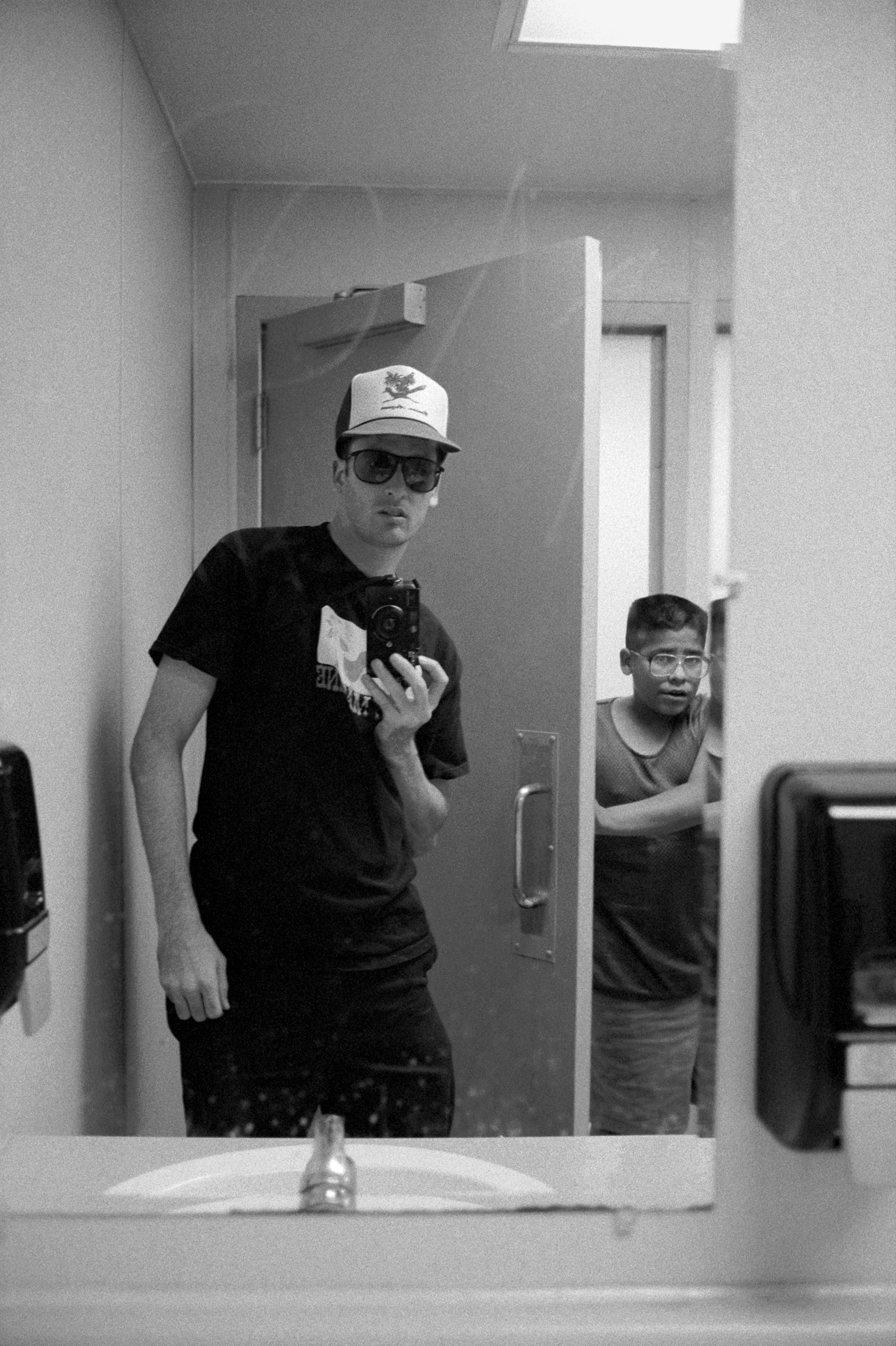

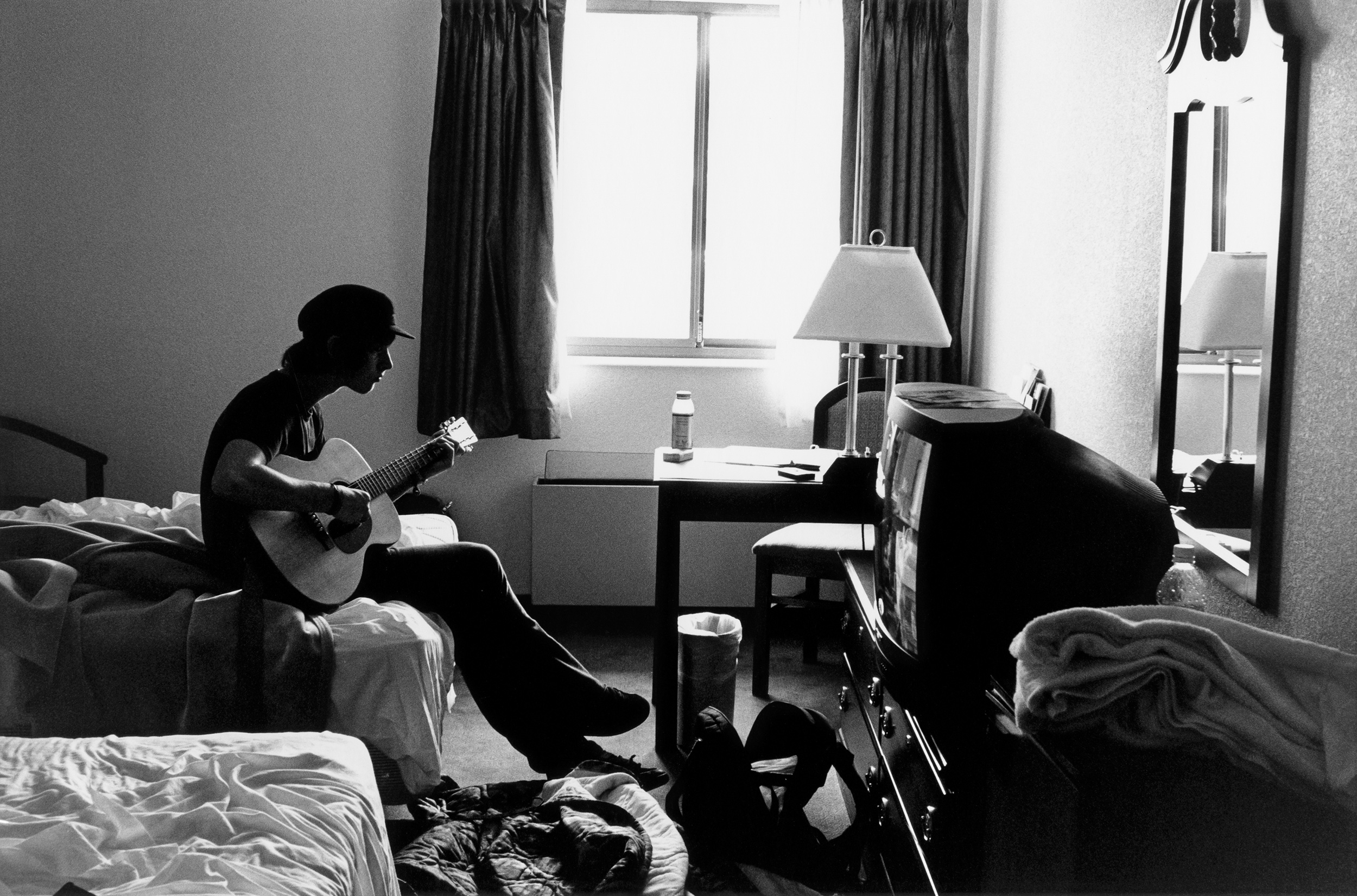

The artist’s recent monograph, Wires Crossed (Aperture, 2023), offers an insider’s look at a subculture in the making and reflects the unique aesthetic stamp that sprang from the skate world Templeton helped create. Part memoir, part document of the DIY, punk-infused skateboarding community, the volume is illustrated with photographs, collages, texts, maps, and other ephemera from Templeton’s journals. This work, much of it previously unpublished and unseen, explores Templeton’s own journey as an image-maker, as well as the lives of professional skateboarders as they spent long hours crisscrossing the world on tour, reveling in their newfound status as rock star–like figures and the eternal search for new terrain to skate.

Here, the editor Lesley A. Martin speaks with Templeton about his entry into photography, being part of the coming of age of skateboarding in the 1990s and early 2000s, and condensing twenty-plus years of image-making into his monograph.

Lesley A. Martin: So, Ed—let’s start with a little bit of exposition for those who know you primarily through your photography: what is a Toy Machine? What is a skate demo? Who are these people in the book? What is going on?

Ed Templeton: Toy Machine is the name of a skateboard brand. I started it in 1993. We make, market, and sell skateboard decks for the most part, along with videos, wheels, t-shirts, and accessories, but mainly skateboard decks. Since the beginning we have sponsored a team of skateboarders, both amateurs and professionals. We discover skaters we think are great and sponsor them with free product. And then they move up the ladder, becoming a paid amateur, and then go pro.

Going pro means you have your name on a skateboard deck. It’s like Lebron James having his name on a pair of Nikes, but on a way smaller scale. When you go pro for skating you get paid more, both a monthly stipend and a royalty from the sales of your signature board. Many of these pros also have shoe sponsors and clothing sponsors that pay them. The top guys with a lot of sponsors and endorsement deals can earn into the high-six figures, and a rare few into seven figures. But in reality the bulk of pros earn in the mid-five figures.

To have a shoe and a deck with your name means you, to put it crassly, have become a marketable commodity, a celebrity in the skate microcosm. And the way you become that is through skateboard videos and having a presence in skateboard magazines.

Martin: It seems like being a pro skater also means being really good at crafting a cool personal image—about creating the perfect avatar, even in the days before social media?

Templeton: Video clips are our primary cultural currency. As a skateboard company our main interface with the public comes from our ads in skateboard magazines and our videos. The skaters we sponsor, their main job is to go out and skate, and bring back video clips and photographs. We use these photos and video clips in our promotional materials—print ads and Instagram posts, etc.

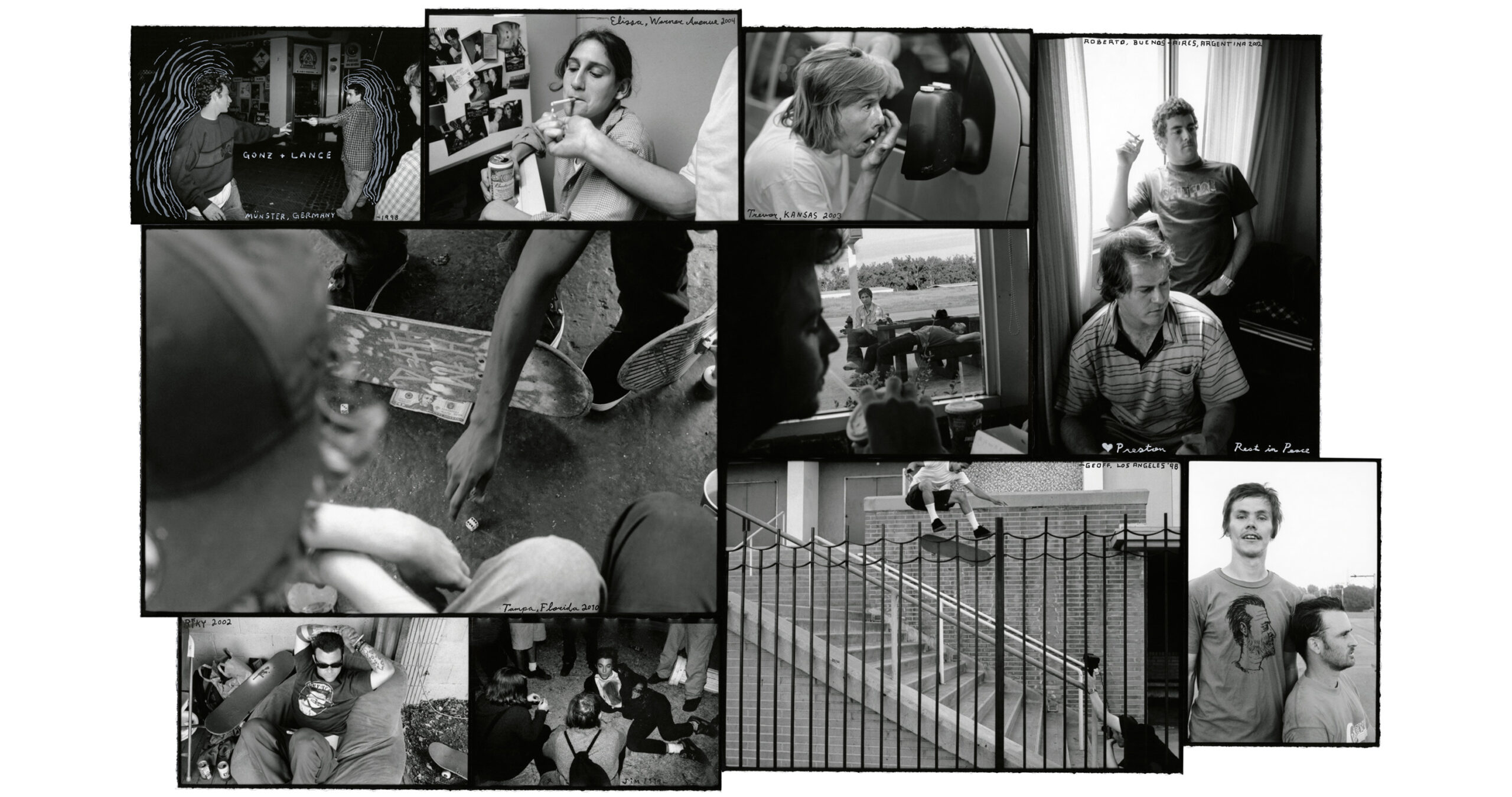

A time-honored tradition in skateboarding is for a company to make a branded skateboard video. A team will travel the world filming in different locations, collecting video foot- age, and then we edit it all together, each pro having their own part with their own music. This is a way for the personality and style of each individual skater to shine through. And these parts are what make a skater known to the world. Skate celebrities are born out of these videos. The people in the photo- graphs in this book are pro and amateur skateboarders, many of them were sponsored by Toy Machine, or some other company I was associated with, and that means we would travel together on demo tours.

A skateboard demo tour is exactly the same as a band going on tour. There’s the talent, the equipment, the support crew, and the media all piled into a van and holding live performances hosted by various skate shops. Sometimes we skate on a crappy asphalt parking lot at a strip mall with makeshift wooden ramps, and other times we get a shiny new cement skatepark. The shops pay us for the appearance, we skate for the crowd that shows up, and then we usually hang around skating with the locals and signing autographs. The tours last anywhere from two weeks to a month, usually during summer months.

Martin: I’m interested in what was happening in 1993 that made it a good time for you to start something like Toy Machine, and how the scene around skate culture has changed since then.

Templeton: It was a terrible time, really. From 1990 to 1991 I had a great sponsor called New Deal Skateboards. That first year they sent me to Europe to compete in the contest circuit and I ended up winning all of the key contests. One of them was the World Championships in Münster, Germany. So I became world champion at age eighteen, my first year being a pro. I had a little cultural capital in the skateboard world, and that’s probably why I thought I might be able to strike out on my own. I had a friend on the team, Mike Vallely who had always wanted to start his own company. He talked me into leaving New Deal to start something with him. Our company was called “TV.” I don’t think we fully knew what we were doing. Skateboarding as a whole had shrunk; it was really a low point in skateboarding. Money was tight, and it caused a lot of strife. We dissolved the whole thing rather quickly. The year 1992 was hard for me. I had no job and no prospects. I was calling everybody in the industry trying to find a place to start my own company. The fallback would be to just get sponsored by another company as a pro skater. But for me, once I got the taste of doing it myself, I wanted to do my own brand. I liked the idea of calling the shots. But I didn’t have any money. I’m just a guy with an idea and a name in skateboarding trying to pitch company ideas to people who had companies already. Finally, that worked. The guy who had done Vision Skateboards, Brad Dorfman, listened to my pitch and said, “Okay, let’s do it.” So I started Toy Machine, and he was the financial backer. After a year, I was approached by Tod Swank, a former pro skater and owner of Foundation Skateboards. He wanted Toy Machine to join his skateboard distribution hub. We made a hand- shake deal. That was nearly thirty years ago now. Our main thing is making skateboards. And traditionally it was videos, too, although that aspect has changed now with Instagram, YouTube, and everything like that. In the early days, videos were a big part of our yearly sales. We would make a video and sell that video. Now everybody expects it all for free.

Martin: So, you’re a media company too.

Templeton: Essentially, Toy Machine is a marketing company. Because for the most part all skateboards are exactly the same. They’re all seven-ply hard rock Canadian maple decks with different marketing applied to them. What makes Toy Machine different is our style, graphics, team, and brand identity. That’s what I do. I do the graphics, and set the tone, language, and ethos for the company. That style is reflected in our videos and advertisements. The kind of skaters we sponsor, the music, the visuals, all that is what makes people want to buy something from Toy Machine.

Martin: How would you describe a Toy Machine skater, or the Toy Machine ethos?

Templeton: I came to the realization that I’m responsible for marketing and selling the very thing I love, skateboarding, which gave me some cognitive dissonance. I hate the concept of advertising and the psychological gymnastics that go into selling and advertising something. My solution to this was that everything should be a joke and that I should dial up the crass commercialism to eleven. I asked myself, “What would the marketers at Nike or Big Pharma wish they could say or do to sell their product but can’t?” The central concept for me has always been mind control, brainwashing, and indoctrination. Toy Machine has a thing called the Consumer Control Center—our full name for it is Toy Machine: A Bloodsucking Skateboard Company. It’s something right out of Orwell’s 1984. We call the fans of Toy Machine our Loyal Pawns. Even using the word “Bloodsucking” was never meant to invoke vampires but a kind of money-grubbing corporation. And so all of our marketing language has always been stuff like, “We control your minds and your credit card, purchasing Toy Machine is not a choice, it’s mandatory.” And our fans get the joke, they know it’s all tongue in cheek. Every time I sit down to design an ad, I know I’m talking directly to a fifteen-year-old reading their skateboard magazine in detention. I was that kid once too, so I wonder what would make them chuckle. I’ll say something like, “Get addicted to the most powerful drug on the planet, skateboarding.” Stuff Nike could never get away with because it’s just too caustic. We are not taking ourselves too seriously.

Another part of Toy Machine’s identity is that skateboarding always comes first. So all the stuff I just talked about is just the window dressing, the decoration. The central principle is great skateboarding. Our ads and videos are filled with really great skaters. But we never sponsored skaters just because they were great, that would be like having a team of robots. For us talent is number one, but a close number two is personality and style.

Martin: I’m thinking about your association in the mid- to late-’90s with the Beautiful Losers movement, which really was one of the first to forefront graffiti and skate artists with subcultural roots. Can you tell me a little bit about how you thought of yourself as an artist when you were first starting out? Because on one hand you’re a skater, but on the other hand you’re talking about this image making, and image creation, and creative life too.

Templeton: The minute I found skateboarding, I was immersed in a world of creative people—even as far back as middle school. Having a skateboard was the ticket into a new world. There were these two punk guys I had always steered clear of. I thought these guys wanted to kick my ass. But once I had a skateboard under my arm they were like, “Hey, come hang out with us.” They gave me a cassette tape with Dead Kennedys and other bands. My mind was blown. The Beautiful Losers cluster—I think we are all loathe to call it a “movement”— was the same. I mean Thomas Campbell, who was also in the Beautiful Losers exhibition, is someone who I met because he was shooting photos for skateboard magazines. He was shooting me for my interview in Transworld Skateboarding magazine. Aaron Rose, who was the visionary mastermind behind it all, was running Alleged Gallery in New York. It was on Ludlow Street. And he was giving skateboarders the chance to show their artwork. In 1994 I did my first show there called Waiting for the Earth to Explode. I’d been aware of the art world from early on. In 1990, the same year I turned pro for skating, I started painting. On that first trip to Europe, I went to see museums when I wasn’t skating because I really thought this might be my only chance to see Europe. I wanted to squeeze as much out of it as I could. I came back from that trip declaring, naively, “I’m gonna be a painter!” So my art life and my skateboard life have been on a parallel track from the beginning. Most people know me from skateboarding, but a lot of people from the art world were unaware that I was a skateboarder. Photography came four years later. And this book is a culmination of literally my first idea as a photographer, which was to document this culture that I’m part of.

This book is a culmination of literally my first idea as a photographer, which was to document this culture that I’m part of.

Martin: What was it that prompted your embrace of photography?

Templeton: I think it was two things really. Thomas Campbell was going on a surf trip to Morocco for several months and he asked me to take care of his art books while he was gone. Among the stack of books were Teenage Lust by Larry Clark and The Ballad of Sexual Dependency by Nan Goldin. Up to that point I had a naive view of what capital-P Photography could be. I thought it was more like National Geographic–style documentary or going out on assignment to cover something, like war or famine.

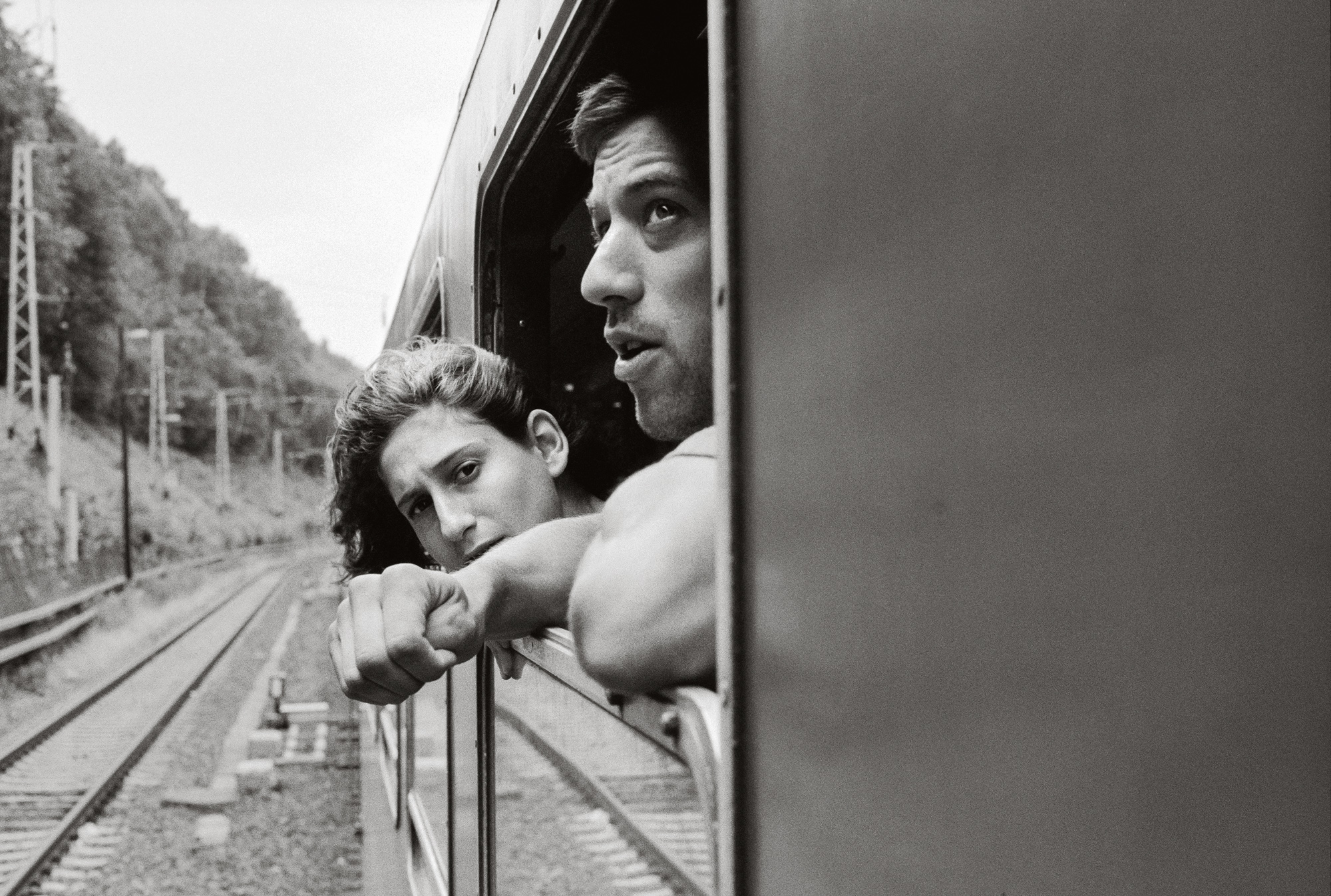

Seeing the photographs in those two books had a big impact on me—they changed my understanding of photography. These artists were not going out and shooting something happening in the outside world, they were shooting their own world, giving us all a glimpse into their slice of life and time and the particular way in which they saw it. So here I am traveling the world with these amazing people who get paid to skateboard for a living. They’re celebrities in their world. They skate hard every day and party hard every night, acting like rockstars with a “live fast, die young” sort of mentality, and I’m one of them. I came to the realization that I should be documenting this incredible life I get to live. I felt dismayed that I wasted four years.

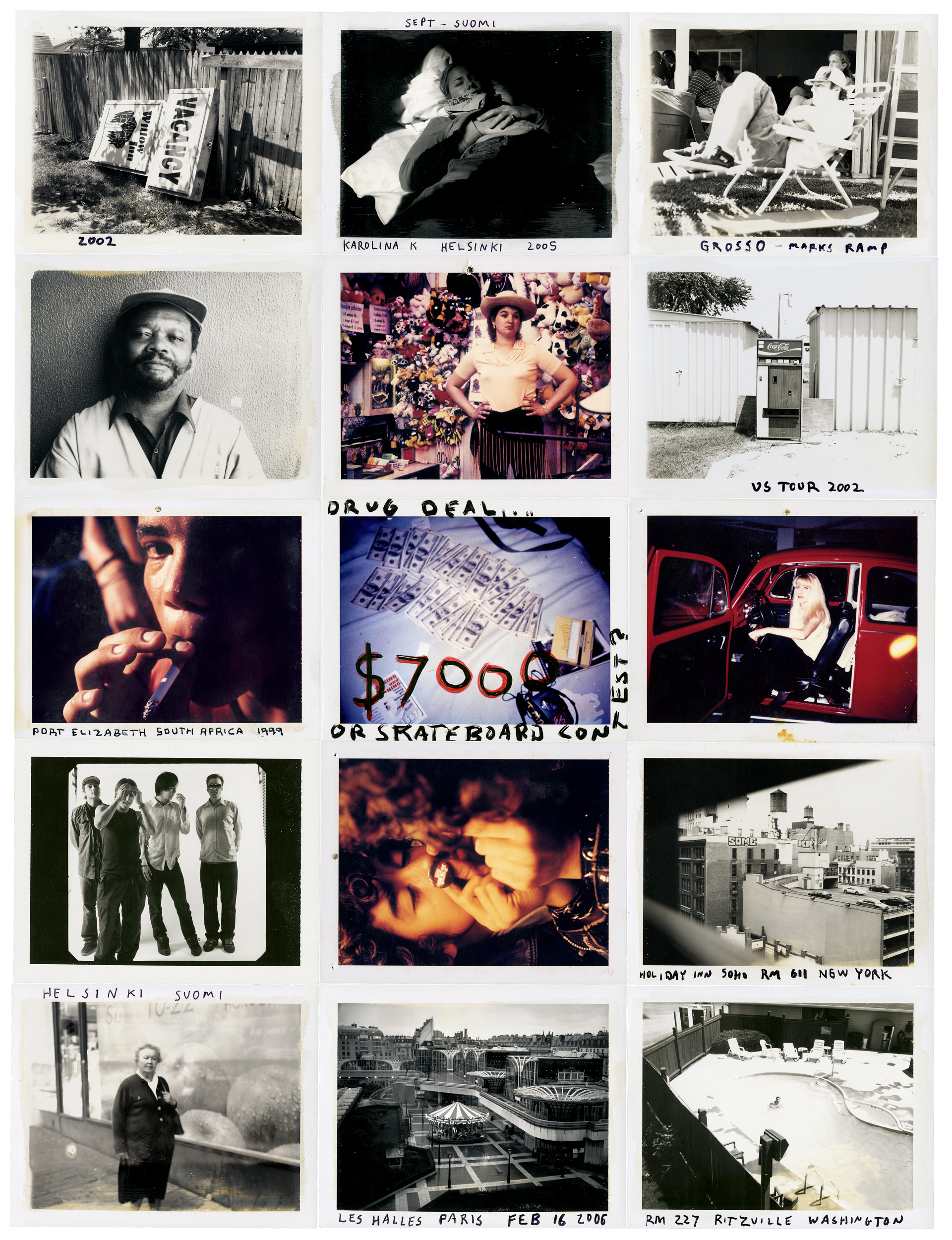

Image collage by Ed Templeton, 1998–2010

Martin: But you kept sketchbooks full of notes, drawings, and ephemera from the beginning of your life on the road, correct?

Templeton: Yeah. I did keep a spotty diary. I wasn’t as diligent as I should have been, but I do have notes from over the years. I always kept a sketchbook with me because I like to draw. It was mostly crappy sketches and little notes about what happened that day and where we were—nothing profound, no deep thoughts about life. But as time went on, these books got more elaborate and I started really keeping more of a diary. Now the diary part has almost squished out the drawings and a lot of the pages are all text. They were really helpful in making this book.

Martin: How did you draw on those journals for this book—what’s the relationship of what we’re seeing in Wires Crossed to those original sketchbooks?

Templeton: It started as just a reference. Looking at the sketchbooks was just a way to figure out what year or place a photograph was from since I’m kind of spotty about writing dates on proof sheets. But I soon realized that certain diary entries could be a great way to illuminate and contextualize some of the photographs. In many cases I have texts that speak about the photographs themselves or the circumstances leading up to them. I ended up scanning hand-written entries directly out of the book. So you’re seeing what I wrote and what I was thinking at the time.

Martin: I’m curious if you could describe a little bit about what it has meant to you to look back over this time span of twenty-odd years. What has it meant for you personally? And what do you hope is of interest or value to others?

Templeton: It’s been a very rewarding experience. It’s really unbelievable what our life was like and even though I wish I had done an even better job documenting it, it’s pretty trippy looking back and having this rich visual document and being a character in it. I feel like this book has two audiences. At its core it’s a photography book. I started this project to answer the question, “What is it like to be a pro skateboarder?” I wanted to give people an inside glimpse into our world. And I think it works on that level as a photographic document. Fans of photography can see it and enjoy the photographs, the time period, the moments portrayed, and the bigger story being woven together. It’s a time capsule.

But then there’s another audience in the skateboard world who will see in these people the celebrities they grew up watching in skateboard videos and looking at in skateboard magazines. For a skateboarder it’s a behind-the-scenes look at a world they may be familiar with, but I hope this book will give them a deeper insight.

Martin: I’m curious what you’ve learned about your photographic work during the process of looking back. Have you noted an evolution?

Templeton: I had been organizing the photographs for decades. Since skateboarding and photography have been so entwined for me, the work I needed for this book was scattered throughout my archive like a complex root system. It’s hard to extract it all out. I had to systematically look at every photo I had ever shot to determine if it could potentially be in this book, which in itself was a re-education. That first edit was around five thousand photos. Then I set to cutting that in half. Then I would set it aside for a spell before returning to cut it in half again, and so on over many years until I had about two or three hundred photos that could conceivably fit into a book. I have definitely noticed a change in my work from that time to now. It’s hard to quantify. There are things I notice I was doing then that I don’t do now, but also vice-versa. I think overall the longer you look through a camera, the better you get.

One of the things I look back on with regret is how much I missed. I was a participant and an observer. So I was often driving the tour van, which means I couldn’t shoot photos. When we arrived in town for a demo, my job was to skateboard for the kids, sign autographs for two hours, and only then could I can grab my camera and shoot photos. All that time I’m skating and signing autographs there’s all this stuff happening that I’m missing. So I wasn’t as present as a photographer as I could have been. There was a constant struggle deciding what hat to wear.

Martin: Did being behind the camera as an observer put a distance between you and your subjects?

Templeton: Yeah, for sure, but I feel really fortunate that the people who I was on tour with had a real trust in me. They never seemed to care that I was shooting photos. Maybe I had the camera out so often that they just forgot that I had it and didn’t really care. But I mean it wasn’t as intrusive as you might think.

Martin: I think that’s the secret of somebody like Jim Goldberg for example, who I know is another influence of yours. Part of the skill set is learning to be a fly on the wall. Being both there and not there. You’ve published more than twenty books of your photographs. Is all that work a byproduct of being on the road? Or are those projects that you developed conscientiously? Because it seems all intertwined. What makes Wires Crossed stand out or different from the work that you’ve published before?

Templeton: Everything I’ve ever photographed, for the most part, has been something I saw going from point A to point B while doing something else. If I’m on a skate tour, I’m shooting photos of the skaters, but I’m also shooting street photos while I’m walking around, and then that work might end up in other projects. For books of mine like Wayward Cognitions or Tangentially Parenthetical, a lot of that work was probably shot while on a skate tour, but it has nothing to do with skate- boarding. So in that way the work is really tied together on that level. One of my books, The Golden Age of Neglect, has many photos that overlap with Wires Crossed, which has caused me a lot of worry, because I ideally would rather not publish photos more than once. Although that book has a number of photos that fall into Wires Crossed territory, it’s not the whole picture. This book is whole picture.

Wires Crossed Limited Edition book and print set

1200.00

$1,200.00Add to cart

Martin: There is definitely a sense of nostalgia throughout the book. And you talk a little bit about this with Erik Ellington, about how a lot of the work was made in a time before social media, before the post-9/11 hypervigilance about cameras. You said that you don’t think that you could get away with the same type of things now that you did then. I’m wondering how you’ve dealt with that idea of “boys will be boys” running throughout the book, and how that rings today.

Templeton: Yeah, there’s been a lot of personal and a wider cultural evolution that’s happened since this time period. And looking back, a lot of the stuff we did was embarrassing. I cringed reading some of my own journal entries. A lot of it was doing stupid things to entertain ourselves. Buying fireworks, airsoft guns, and squirt guns was a big part of having fun on tour. It’s summertime, you’re outside, and you’re just squirting each other, blasting each other in the face with a big Super Soaker kind of thing.

But then there’s a darker side—one night in Chicago the guys were like, “Let’s drive around and squirt people.” So here I am, a grown man, taking some slightly younger grown men out in a van. We’re driving around Chicago, and they’re opening the side door and blasting people waiting at a bus stop with a Super Soaker. It’s innocent, but it’s also a really lame thing to do to people. I look back and cringe being reminded of this stuff, thinking, “Oh god, we did this?” I was managing a team of young men who have all this energy and testosterone. Sometimes we’d check into a hotel room and they would start just breaking stuff. So I’d be like, “You guys wanna break stuff, let’s get in the van, we’ll go out and break some stuff.” So I would take ’em out and we’d find like an abandoned area or a warehouse district, where they could shoot some lights out, paintball some signs or whatever, just do dumb stuff.

Some of the stuff I was documenting would fall under the term “toxic masculinity” today. There was a lot of woman-chasing. I mean, I was happily married the whole time, so I had the remove of the camera and I had the remove of being married. Women fans at skate demos would come up to me and ask me to sign their breasts, and I would reply, “I’m sorry, my wife wouldn’t appreciate that, but my fellow pro Matt Bennett over here would love to sign your boobs!” And then I would step back and shoot a photo of that happening. Also, a lot of the language used was pretty harsh. We’d say, “That’s gay” or “That’s faggot shit” but never in a way that was literally about gay people. Now we can unpack how even that’s wrong—the roots of that term stem from misguided stereotypes about gay people or women. We have all evolved our language for the better since then.

Martin: I think there’s so much to unpack. I mean it’s about time, it’s about the changing perceptions of how you expressed yourself, who people are allowed to be. And it’s interesting how much that comes through in your conversations with them.

Templeton: Yeah, in talking with Brian Anderson, he doesn’t carry memories of that language as something that was a persecution. He knew that his teammates weren’t homophobic. I was so secure in my heterosexuality that it didn’t bother me to hug the guys or show affection. Many people in the skate world thought I was gay. For years, people thought my wife Deanna was a beard. Big Brother magazine had this monthly write-in column called the “He-Man Ed-Haters Club” based on this. Big Brother was owned by Steve Rocco and run by Jeff Tremaine and Sean Cliver, the guys who do Jackass movies now. The He-Man Ed-Haters Club started because I wrote an article poking fun at snowboard fashion. Some snowboarders took offense to it and they got a bunch of letters from people saying, “Fuck Ed Templeton.” And I think they got enough letters where it was like, “Let’s start a club.” So they invited people to send in Ed Templeton hate mail. It was fun for a while until of course it got out of control. There was lots of ugly homophobia, and then death threats, so we stopped it.

I had a list of messages that I printed out before the tour and taped them to the flip-down visor. They were responses to complaints I might get from the team while driving. Stuff like, “stop whining,” “save it,” etc. So whenever someone would complain, like, “it’s too hot in here,” or “the music is too loud” I would flip down the visor and point to one of the messages, then violently flip it back up. But one of the messages was, “do I need to stop for tampons?” It was all in good fun, but in today’s culture it’s maybe not so funny. You can get cancelled for that. You can’t criticize a guy for complaining by saying he needs a tampon, ’cause then you’re implying that he’s a girl, and that girls are weak.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Martin: Yes. I think that’s what’s fascinating about having this time capsule portraying this condensed essence of a certain experience of young male adulthood that doesn’t exist now.

Templeton: Being young is about testing the boundaries. In retrospect, many of our interactions with the police were really fraught. We would be caught with these airsoft guns that looked like real guns, out in the streets, shooting cans and stuff in inappropriate areas, like in a Walmart parking lot with people everywhere. Inevitably a cop would roll up and be like, “What are you guys doing? You can’t shoot these guns here.” These days we might be shot right off the bat.

Martin: Well, speaking of terms that did not exist in the same way then—toxic masculinity being one of them, white privilege being another one.

Templeton: Total white privilege, for sure. We had no fear of the cops. As a team of mostly white skaters crisscrossing the country, we felt bound by no laws. I write about that at the end. We felt like outlaws in the Wild West, like we really could do whatever we wanted.

Martin: Do you think that’s the same these days?

Templeton: I don’t think it’s changed that much. I think going on a skate tour right now would almost be the same. It wouldn’t be a good idea to be making firework bombs, and brandishing air-soft guns around. Aside from those two things, I think a team of white skaters could pretty much get away with whatever they want still in these United States. Now, there’s something to unpack.

This interview originally appeared in Wires Crossed (Aperture, 2023).