Interviews

Heinkuhn Oh’s People of the Twenty-First Century

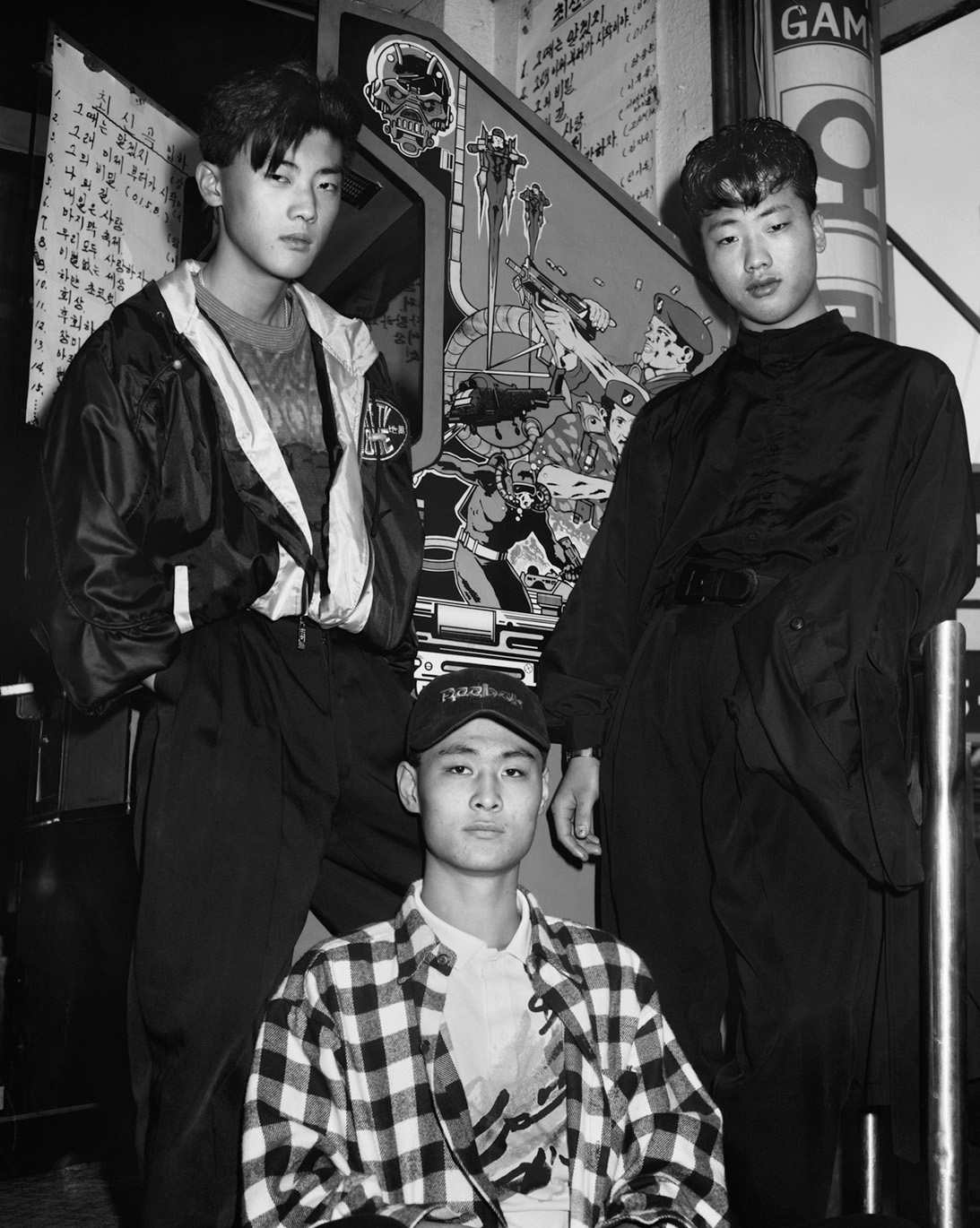

In mural-scale portraits of high schoolers, soldiers, and other social types, Oh subtly dramatizes tensions between collective and personal identity in Korean society.

Heinkuhn Oh rose to prominence with his photographs of social types—high school students, cosmetic girls, soldiers—often printed at gargantuan scale. Their faces greet visitors to Oh’s airy studio in southern Seoul. Uncanny, at times disarming expressions hint at the layered ambiguity present throughout his work. Although Oh’s portraits emerged from discrete series dedicated to groups, each subject’s eccentricities break through such categories, subtly dramatizing tensions between collective and personal identity in Korean society.

Oh’s early work was informed by his ambition to become a filmmaker and his years living and traveling in the United States. Equally influential was his experience growing up in Itaewon, a neighborhood in Seoul that was once a roiling tenderloin whose nightclubs and brothels catered to US soldiers. Today, it is one of the city’s trendiest neighborhoods, with bustling cafés, chic boutiques, and roaming influencers. Oh’s breakthrough series, Itaewon Story (1993), is a pregentrification tale, capturing the vivid underground characters who once defined the area. He has described Itaewon as a kind of in-between zone, a space “where people exist between cultures—neither fully one thing nor another.” It is a description that could be applied to Oh’s work as well, where his subjects often reside in liminal states: between the mainstream and the margins, childhood and adulthood, the individual and the collective, fiction and reality.

Hyunjung Son: For readers new to your work, could you tell us about your background and what drew you to photography?

Heinkuhn Oh: Originally, my dream was to become a film director. I went to the United States to study filmmaking, but along the way, I fell in love with photography—more precisely, with documentary photography. I ended up going to graduate school and majoring in photography, but near the end, I still felt something was missing, so I added film as a second major. However, I ultimately received my final degree only in photography. I became so absorbed in my thesis project, Americans Them, that I didn’t have the time or energy to complete a film thesis. My mind was filled with the work of Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus. Honestly, it was far more exciting to me than anything from Scorsese or Coppola.

From 1989 to 1991, I spent three crazy years traveling across cities in Ohio, West Virginia, and Illinois for Americans Them. Eventually, I made my way south to New Orleans. The camera I used back then was a fifty-year-old secondhand Speed Graphic, which I bought from a used-camera shop in Columbus. I attached a Metz flash to it and shot with 4-by-5-inch Type 55 Polaroid film. I felt like I had become Weegee. Initially, I used the camera’s range finder, but later, I started shooting everything by eye measurement. Although many shots came out of focus, not using the viewfinder made me look at my subjects with my naked eyes. It was a wonderful thing. These days, as I’m reprinting Americans Them, I realize just how much I learned about people and their gazes through that project.

Son: This word gaze comes up often when describing your work. You’ve said you discover, rather than create, these gazes.

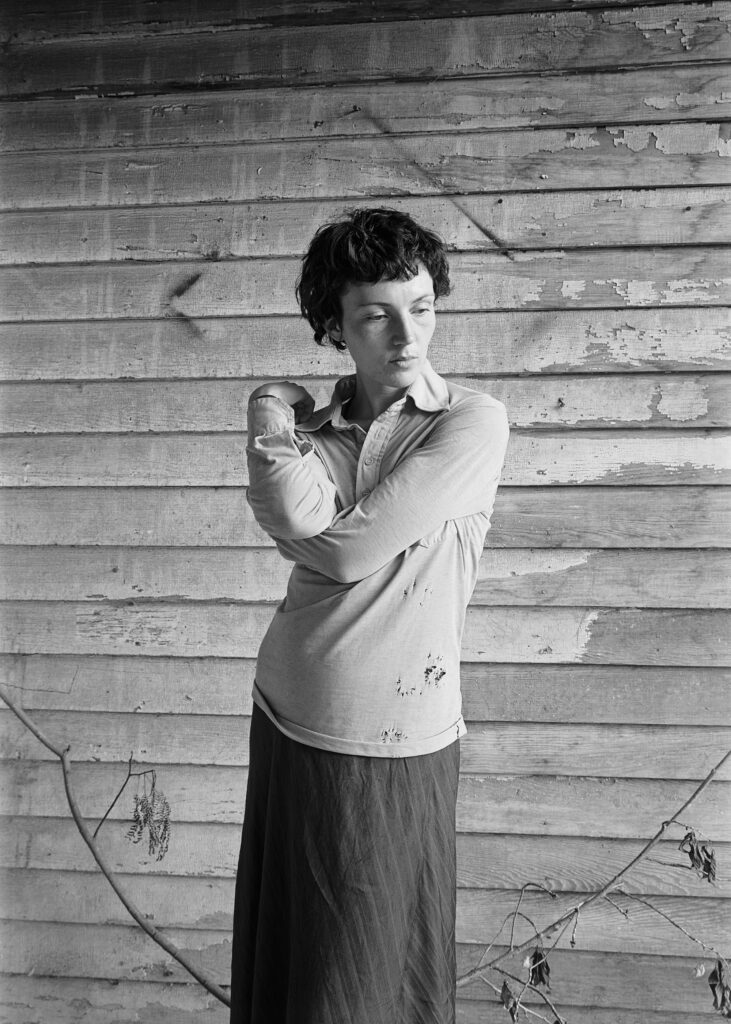

Oh: In the late 1990s, I wanted to document the anxiety and social isolation experienced by middle-aged women in Korea, which was very much a country of ajeossi [middle-aged men]. This led me to photograph ajumma [middle-aged women]. Instead of taking the documentary approach I might have used earlier, I went directly to portraits. I had realized that if I could capture the narrative in their gazes and expressions, no further explanation was needed.

Creating a multilayered gaze artificially is impossible. These layers accumulate naturally through lived experience, visible in people’s expressions. The process of finding such gazes is time intensive. For my series Ajumma (1997), while the actual photography took less than two months, the casting period took over a year. I’ve done a lot of movie poster work as well, so I’ve sometimes been asked questions about the gaze of celebrities versus ordinary people. One question I received was, “What is the difference between the gaze of actors and that of ordinary people in your work?” With actors, I work to create layers in their gazes, while with ordinary people, I discover the layers already present in their expressions.

It was the same with my Cosmetic Girls (2005–8) project. From 2005 to 2007, I cast around five hundred heavily made-up teenage girls directly from the streets. Over the course of three years, I photographed one or two of them each day, and from those portraits, I looked for the gazes that carried the deepest layers of anxiety. This is because I believed that for these girls, makeup was an act of concealing their anxiety.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Son: Your use of the term casting is interesting, coming from your film background. How do you actually find and photograph your subjects?

Oh: My approach mirrors film casting because I believe great directors don’t so much direct actors as find the right people for each role. Once cast properly, actors naturally embody their characters. Similarly, I don’t try to create complex gazes—I find people who naturally possess them. My role then becomes creating the trust needed for them to reveal their authentic selves to the camera. That’s often the most challenging part.

Son: You’ve done a lot of commercial photography, including the movie posters you mentioned. How did you start this work?

Oh: In fact, all of my early black-and-white works are closely tied to my film background. Even Americans Them was fundamentally about capturing Americans as they appeared to be performing their lives as if in films—playing out cinematic storytelling or role-playing characters from movies. It seemed to me that they dressed, posed, and even joked as if they were in a film. It often reminded me of the movies by the Coen brothers. Itaewon Story was like an autobiographical film for me, capturing the images of celebrities I grew up watching in Itaewon during my childhood.

Son: Your series Middlemen (2010–13) features military portraits, but I heard it was originally titled Absurd Play. Why did you change it?

Oh: In Korea, there is a mandatory system where most men serve in the military for a certain period. I, too, went to the military through this system when I was young, and after time passed, I came to look at that space again through photography. I completed my military service about thirty years ago. As a young man, my view of military service was straight-forward—it was about patriotism and duty. Returning to photograph the military in my fifties, everything appeared strange and awkward. The experience felt like watching an absurd play unfold, which inspired the original title. However, two months before the exhibition, our cultural liaison officer at the Ministry of National Defense privately expressed concern. The higher-ups had reacted negatively to the word absurd, interpreting it as suggesting something dysfunctional or improper. To protect our helpful liaison, I changed the title to Middlemen.

The work became subtitled Portraits of Young Korean Soldiers. During my two years observing these men, I recognized how they existed in a liminal state—neither fully civilian nor completely military. This realization led to the title Middlemen. It also sparked my broader interest in exploring these in-between states in society and, by extension, the nature of absurdity itself.

I don’t try to create complex gazes—I find people who naturally possess them.

Son: Would you share how you created works like the fighter pilot photographs?

Oh: For most of the photographs in my Middlemen project, the shooting process wasn’t particularly difficult. I didn’t try to capture or request any scenes that the military might find sensitive or uncomfortable. However, there was always a cultural liaison officer monitoring the images on a laptop connected to my camera—essentially conducting censorship. They said it was to prevent any accidental capture of military secrets, but I think they were really worried I might show something negative about the military. After a while, the officer even joked, “Why are you taking such boring pictures?”

But the fighter pilot shot was one that gave me a lot of trouble, even with this kindhearted liaison officer. The problem arose when I asked them to briefly halt a fighter jet during an operation. I thought they could simply stop it on the runway for a moment, not realizing that a fighter jet isn’t an automobile and costs tens of millions of dollars. Moreover, this was a military operational area, and stopping on the runway required approval from multiple levels of command. Eventually, the approval came through, and they did stop the jet, but the photography session took longer than expected. The officer kept pressuring me to hurry because the operation was ongoing, and the pilot was becoming increasingly irritated. What I found most interesting in this photograph, though, wasn’t the huge fighter jet or the pilot—it was the transparent canopy, stretching wide and open into the sky.

There was an incident that I couldn’t capture in a photograph, but even now, it remains with me like a trauma. During a shoot, I suddenly heard a sharp, piercing scream from behind me. When I quickly turned around, I saw something wrapped in a white cloth falling through the air. A soldier had jumped from an open window, from about the fifth floor of a building behind me. Tragically, I later heard that he had died. Military officials told me that the soldier had been suffering from severe depression, and that such incidents, while uncommon, did occur in the military.

Son: Your exhibition prints, including the Middlemen series, are often very large in scale. Why?

Oh: Starting with my Cosmetic Girls series, which I released in 2008, the scale of my work began to expand. There are two techniques in typological photography that can shift the subject toward abstraction: One is repetition, and the other is scale.

Cosmetic Girls was a portrait project that presented heavily made-up teenage girls in a format resembling a social report. The expressionless gazes of different girls were captured under identical lighting and with consistent framing, repeated again and again. At first, it may seem like each girl is being presented individually and concretely, but ultimately, through repetition, the images dissolve into abstraction.

I believe that when a photograph becomes excessively large, the subject itself begins to feel unfamiliar. This is one of the great ironies of large-scale photography. Especially in portraiture, the bigger the print, the more anonymous the subject becomes. I wanted the girls I photographed to appear anonymous and estranged. Because, for me, the series is ultimately about the underlying anxiety surrounding identity in Korean society that stems from feelings of anonymity, estrangement, disappearance, and abstraction.

In my more recent series, Left Face (2020–ongoing), the prints are also relatively large. But this time, the reason is slightly different. Lately, I’ve gotten interested in how large photographs create abstraction through their very obviousness. I think big photographs have this interesting thing where they switch between being clear and abstract. Having spent many years working in photography, I’ve started to feel that photography isn’t really about representation—it’s about abstraction, simply because it’s too obvious and straightforward.

Son: You’ve contrasted your philosophy with Henri Cartier-Bresson’s famous idea of the “decisive moment” by telling your students, “Don’t be decisive.”

Oh: Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” refers to visual rather than conceptual decisiveness. However, I’ve come to believe that our contemporary world resists such clean distinctions. If photography reflects society, and society increasingly defies logical categorization, then perhaps photography should embrace this ambiguity. That’s why I tell my students, “Don’t be decisive.” Definitive statements and clear conclusions feel increasingly out of step with reality. When everything exists in shades of gray, why chase decisive moments? Even Cartier-Bresson often captured scenes that highlighted life’s fundamental absurdity.

Son: You have taught photography for many years. How has this shaped your thinking on image making?

Oh: Well, I’ve always tried to approach my students as an artist rather than as an educator. Observing the younger generation of photographers today, I feel they have highly developed visual sensibilities. But perhaps that’s only natural, as they consume so many more images than previous generations. During critique sessions, I often tell my students, “You are image addicts!” It’s as if they confuse reality and images. Today’s students look at reality and capture it as images, then look at images and discuss them as reality. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with this approach, I wish they could distinguish between the two.

Son: Your early 1990s series Itaewon Story continues to resonate today. What makes it significant to you?

Though the US Eighth Army has relocated, Itaewon remains a unique cultural space. The Seoul Central Mosque, situated at the neighborhood’s highest point, has drawn a significant Arab community, adding to the area’s diverse mix of residents. Yet calling Itaewon truly multicultural might be an overstatement. Different groups coexist physically but rarely truly integrate. This makes it a place where people exist between cultures—neither fully one thing nor another. It’s fitting that Itaewon sits geographically at Seoul’s center, embodying this in-betweenness. Sometimes I wonder if this fascination with in-between states is my destiny—the space between cultures, between definitions, between artistic forms.

Son: Photography seems to be gaining more recognition in Korea’s art world. What changes have you observed? And what concerns you as a photographer?

Oh: The landscape has definitely improved. More exhibition opportunities exist now, and major institutions increasingly embrace photography as contemporary art. We’re seeing more photography exhibitions in prestigious venues and more international exchange. However, I still maintain that there’s a distinction between photography within art and photography as its own medium. While this might seem like an outdated view in today’s cross-disciplinary art world, I believe photography maintains its own singular territory. We have plenty of discussions about photography in terms of aesthetics and social impact, but I miss deeper conversations about the fundamental elements that make photography unique as a medium.

Son: What directions are you exploring now? And what’s next for your work?

Oh: My immediate focus is completing Left Face, a project that has occupied the past five years. Its scope has grown beyond my initial expectations, and I’m still working to bring all the elements together.

I’m currently exploring the intersection of photography and text, but not in the usual documentary sense. I’m exploring how combining highly specific text with portraits can create a new kind of abstraction. I’m also planning to return to Itaewon for a new portrait series. The title is already decided—it’s Lucky Club. It will probably be work about various people living together in an old building in Itaewon. There, I need to find gazes that contain stories once again.

Son: Seoul is changing rapidly today. What’s your attitude toward the city’s development?

Oh: It’s absurd. This was a title I couldn’t use for the Middlemen project, but if I were to address Seoul as a subject, I would want to use it—a massive “absurd play” is unfolding here. Some describe Seoul’s transformation as diverse and dynamic, but I find it contextless and absurd. Yet photographically, I feel that’s what makes Seoul fascinating. Sometimes I find myself wondering if I should pick up my Speed Graphic again and head back out to the streets to shoot a documentary like Americans Them. I’ll need to think about whether it would become Koreans Them or Koreans We . . .

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”