Interviews

How Photography Influenced Duro Olowu’s Life in Fashion

From album covers to Yves Saint Laurent, the London-based designer’s curiosity is limitless—and his deep knowledge of photography has informed his way of seeing the world.

The former lawyer turned designer Duro Olowu creates fashion moments on a resolutely human scale. Born in Lagos into a Nigerian Jamaican family, Olowu had a cosmopolitan upbringing, traveling to Europe and absorbing cultural influences ranging from album covers to Yves Saint Laurent. His tenacious curiosity, like his patternmaking, seems limitless—and his deep knowledge of photography has informed his fashion line.

Instead of flashy runway shows, Olowu prefers private viewings that allow him to discuss his patchwork dresses and jacquard coats with the coterie of cultural figures who wear his richly patterned designs. Like him, they appreciate clothes in a context that celebrates collecting antiques, paintings, and handicrafts over any proximity to trends or celebrity endorsements. Olowu has also curated exhibitions in New York, London, and Chicago. On each occasion, he staged a vibrant dialogue, juxtaposing photography and painting, or West African heritage textiles and the innovative fabric creations of contemporary sculptors.

The editor Dan Thawley recently spoke with Olowu from his studio in Mason’s Yard, in London. Olowu claims to have been a reluctant curator at first. Soon, however, he sensed a freedom in making exhibitions, the freedom to think about photography and fashion across genres and decades. The results offer a new way of seeing.

Photograph by Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Courtesy the artist

Dan Thawley: Duro, there are some things I am curious to ask you about your relationship with photography. I wanted to start with collecting.

Duro Olowu: I always shy away from the word collect. But I have quite a lot of photography, just because it was always a lot more accessible. In the 1990s and even up until the mid-2000s you could come across something one had always wanted, like an early Samuel Fosso or a Luigi Ghirri. Back then a lot of photography was just not recognized or put in the same category as fine art.

Thawley: What is your relationship to photography as a fashion designer? The image of clothing is something you need to continue to produce, but it’s also something that I can imagine is a powerful tool to inspire your creativity as well.

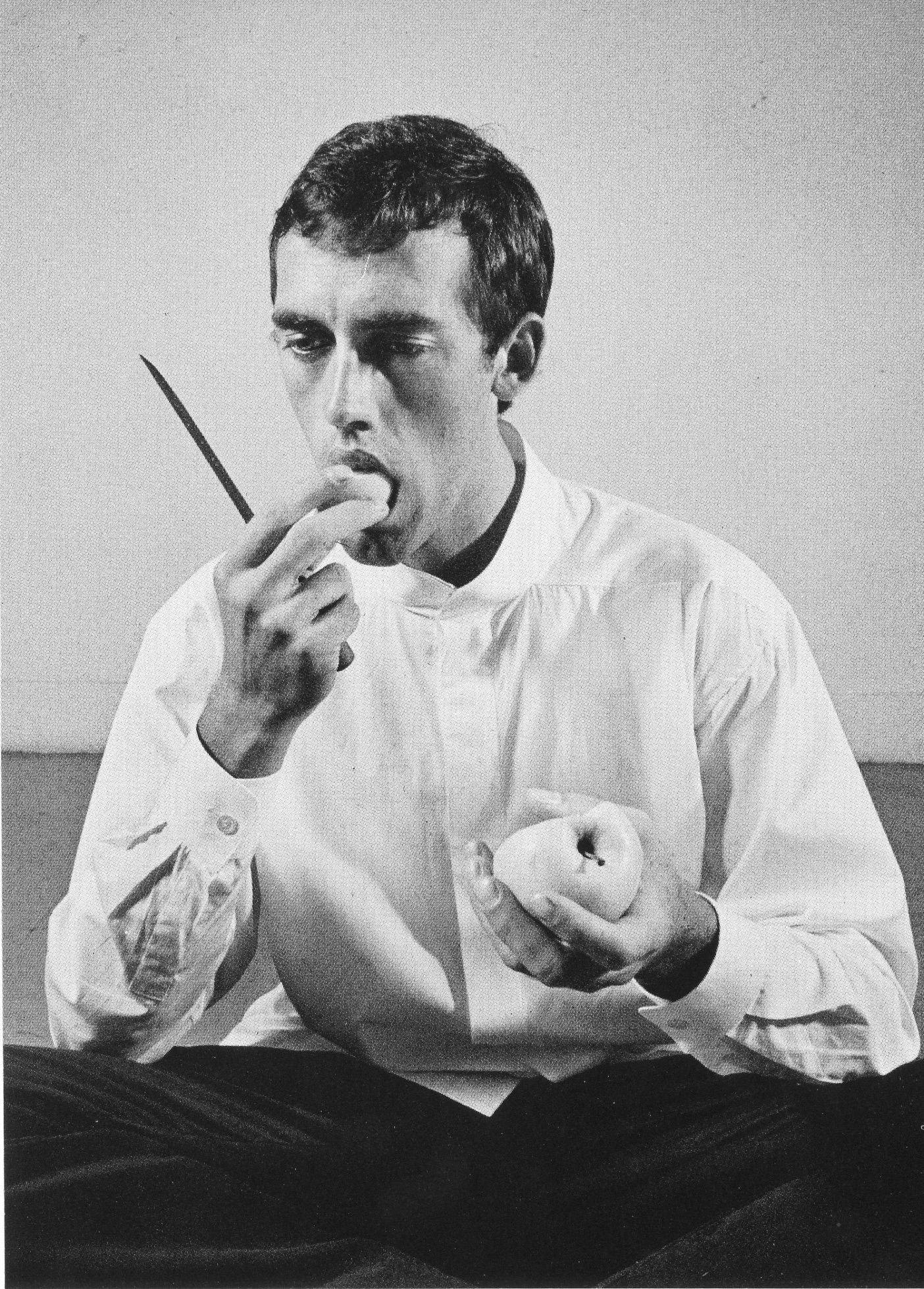

Olowu: There are two aspects to that. There’s a side of fashion photography which is very commercial, and then, of course, there’s contemporary art and photography in that realm. There’s overlap. The relationship between design and fashion and other kinds of creativity has always been there since the 1920s and ’30s, and in the work of a lot of photographers that I look at now—Peter Hujar, Kwame Brathwaite, Cindy Sherman, Anthony Barboza—people whose work I find as important as, say, Man Ray. I think it’s a subconscious thing.

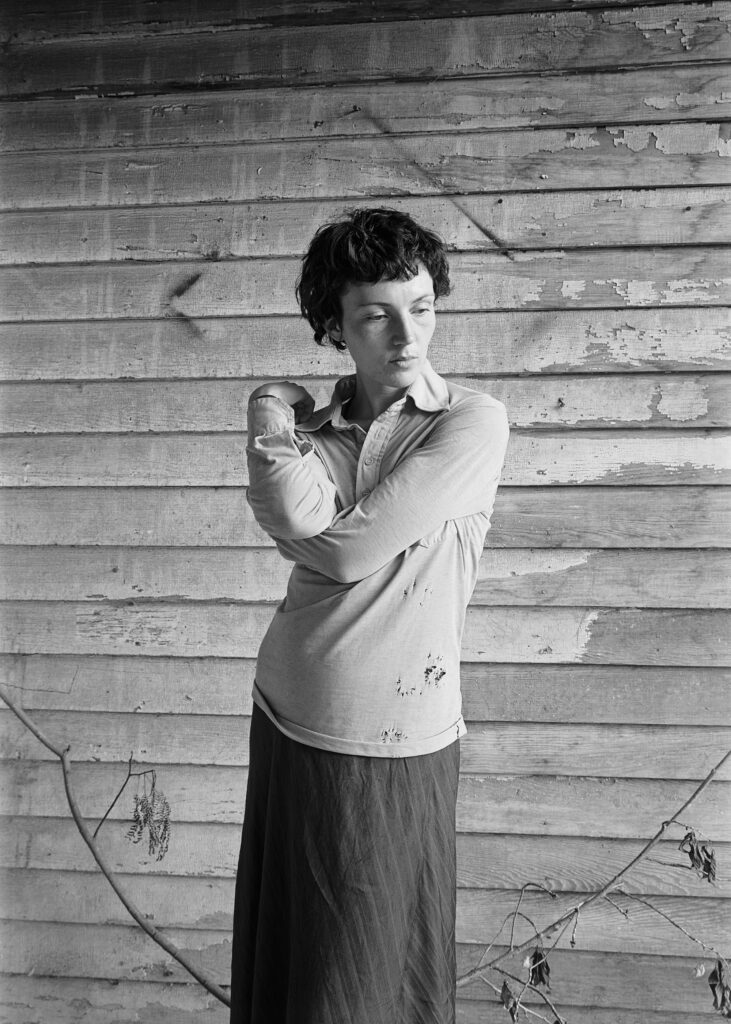

For designers, you can only tell if you have succeeded when you look at a photograph of someone dressed in your clothes, and they look very comfortable and confident—almost as though the clothes have become their armor, their shield. With great photographers, I always found that this was what they were able to do. Claude Cahun used clothing, objects, jewelry, and costume to empower herself as a very early pioneer of self-portraiture in photography and queer art. When you look at Malick Sidibé or Seydou Keïta or Carrie Mae Weems, you realize that they are using clothes as a language. So, as a designer, that is the language that I try to write with.

Clothing to me is not about fashion or trends. I’m designing for people who are interested in the culture of style, and people who want to use what I design to place themselves in the world in a certain way. For something to look modern and for something not to date or age, it has to ref lect the times. I think great photography always reflects the present as much as the past. And in designing, that’s what I try to do with clothing—not to replicate. It’s my point of view. It’s not an attempt to replicate what’s in photographs. It’s more an attempt to emulate the power of the gesture of photographs.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Thawley: Does the way that a photograph freezes a silhouette—perhaps a drape in movement—ever stimulate you to replicate that gesture?

Olowu: A great photograph—whether it’s a still life or a portrait or some other kind of composition—is never forced. A great artist knows not just when to click but when the subject and mise-en-scène is just right enough to capture. Clothed or nude, it’s incredibly emotional and powerful.

Fashion or clothing needs to emote, but it shouldn’t be nostalgic. What changes over time are emotions, how people express themselves. That’s what you see in great collections of clothing. If you looked at Madeleine Vionnet then, if you looked at certain things at a certain time, thirty years ago, for example, they probably didn’t seem so radical. Or Sonia Delaunay, or even Patrick Kelly. Today, they appear even more radical than one can imagine.

I think great photography is like that. Which is why, in looking at contemporary photographers, whether it’s Ming Smith or Dawoud Bey, one needs to also be open to the incredible power, savoir faire, and freedom that the history of photography has made possible in the art world. Many great photographers either started as photojournalists or made commercial work, like Madame Yevonde or Eve Arnold. So, I think photography is a very sinuous reference that is not bound by trends. I feel very lucky that I can look at Steven Meisel, who I consider to be one of the greatest fashion photographers ever, or Irving Penn or Clifford Coffin, in the same way I look at James Van Der Zee, Walker Evans, Mama Casset, or Tina Modotti.

© the Peter Hujar Archive and Artists Rights Society, New York

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Thawley: I’ve always appreciated how you spotlight portraiture on your social media. You post photographs of Black luminaries, amongst other fantastic images. How does that research establish your frame of cultural references when designing?

Olowu: There’s a kind of portraiture that involves a whole setup as a souvenir, and then there’s the kind of portraiture made by artists, which I find really powerful, particularly when it’s self-portraiture. Because there are two things at work. There’s the element of exposing oneself, but also that of not exposing too much of oneself, because you have many more years and a lot more ideas that you want to pursue. I approach design questions in the same way.

Sometimes people can go through periods of their lives not being able to put a face to a writer or an artist. Look at Dawoud Bey’s portrait of David Hammons. When you look at these portraits, they are sort of an eye into the reasoning behind Hammons’s work. When one looks at the artist Lee Miller in Man Ray’s photographs, you are not looking at what you imagine to be the personality of the subject. You’re actually looking at what the person does in the real world, because that’s what emerges. The human body is restless. The human mind is laden. You never know what you’re going to get. When I see something that really emotes in that way, I’m always very conscious of how important it is in the context of contemporary art. Placed alongside portraiture in other mediums like painting or sculpture, it’s very important to have the element of the photographic print.

Joel Meyerowitz, Gold Corner, New York, 1974

© the artist and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Thawley: You’ve curated some great shows, including Making & Unmaking at the Camden Art Centre in London in 2016 and Seeing Chicago at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago four years later. How do you go about manifesting your passion for photography in these projects?

Olowu: I feel that what I do curatorially is a very important part of my whole oeuvre. I see it as an extension of what I do, and in the institutional shows I’ve done, the amount of photography is a testament to what we’re talking about. To have Henri Matisse and David Hammons and Brice Marden next to Dawoud Bey was something that, even curatorially, I know a lot of the people, when I was putting the show together, couldn’t understand until they walked into the room.

I consider photographers to be artists and artists to be photographers. I never think: Oh, do I have to create a special section for photography? I’m actually very anti that. I’m not saying museums shouldn’t have a Diane Arbus show, a Gordon Parks show, a Malick Sidibé show. I’m not saying that they shouldn’t have their own rooms. But I’m always surprised when the institutional shows that are not solo shows hardly ever include photography. Because I think it’s such a natural thing to include. That’s obviously changing a lot. You see a lot more of that now.

I think photography is a very sinuous reference that is not bound by trends.

In looking at a body of work, say, in the ’80s, how could I look at David Wojnarowicz and not see Peter Hujar? How could I look at artists like Carrie Mae Weems even, and not think of Kara Walker’s work? It’s very different work, but it’s just as emotive: powerful stories of women of color, emoting how they feel, not just about themselves but how they’ve been thought of for centuries. The same way I look at Eve Arnold’s photographs. I feel that the way she captured the model in Harlem, the way she even captured Marilyn Monroe, came from who she was as a woman, being able to understand what the camera needed to pull out of that. I couldn’t look at that sort of work and think it had to be in a separate section. I could only think of that work in relation to or mixed up with other things.

It’s not such a new idea. I mean, Surrealists did that. You had Man Ray and Claude Cahun mixed up with Jean Arp and Hannah Höch, and the other Dadaists. It wasn’t unusual up until I think the ’60s, when a different kind of mindset came in. That’s changing, or that’s practically changed now. And I always feel it’s important for any show I curate to reflect this deep conversation between all the mediums that continue to exist amongst artists in real life.

Thawley: We all consume so many images on-screen now. But the object of the photograph is such a dynamic thing as well. What do you appreciate about the printed medium, and how it has changed over time?

Olowu: It’s very interesting you bring that up. The first real contact we have with anything that will later sort of place itself in our lives as art is with photographs and prints. As a child, you look at a magazine or you look at a postcard or you’re handed a photograph. Even practically as a baby, you are often first shown what you look like in a photograph of yourself. Later, as you go from childhood into adulthood, magazines, books, and other visual materials are filled with photographs that define your identity.

I have so much awe and respect for the use of a nondigital camera, the labor and development of film, preferably with no retouching. In looking at the photograph as an object, you’re almost doing so as you would look at a 1920s Paul Poiret dress, Yves Saint Laurent haute couture jacket from the ’70s, or an embroidered midcentury Yoruba agbada robe. You’re looking at how it was made in the same way you look at the fabrication and finish of beautiful garments. So that when you come across it in a museum or gallery, you recognize that it is also powerful, beautiful, and important because of how it was made. Making & Unmaking was all about that human effort. The hand in the work.

© Martini & Ronchetti and courtesy Archivio Lisetta Carmi

© the artist and courtesy Autograph, London

Thawley: We would never know much about certain art practices and movements from the twentieth century if it weren’t for people like Ugo Mulas taking photographs of Lucio Fontana, and all of the Arte Povera artists. Photography reveals relationships and communities. And records from previous generations are so incredibly precious for that very reason.

Olowu: Of course. Once again, the Dawoud Bey photographs of David Hammons with the snowballs. If that hadn’t been documented, how would we know that those snowballs melted—and the political and social commentary therein?

Thawley: How have your interactions with cultural institutions informed your interest in and knowledge about photography?

Olowu: Finding great photography in museums, by both known and unknown artists, is exhilarating and inspiring. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the International Center of Photography, and the Studio Museum in Harlem have exceptional examples in their collections, as does the Art Institute of Chicago. When I’m in Paris, I always visit the Jeu de Paume. The Fondation Cartier presented the first really incredible museum-worthy show of an African artist in the photography world—that was Seydou Keïta’s show there in 1994. It was a beginning in many ways for how work by an artist from the continent was perceived and exhibited abroad.

I recently saw—and was blown away by—the artist Lisetta Carmi’s show at the Estorick Collection, a small museum in London for twentieth-century Italian art. I have to also mention people like Rotimi Fani-Kayode, whom I love, whose work I’ve known for thirty years, and who only now is being recognized. Because of the current possibilities for queer artists, photographers, painters, his work is being revisited and being shown in a very different way. But my favorite is the Photographers’ Gallery in London, a small but renowned museum that I’ve visited since my teens. It exposed me to the most amazing group of inspiring international artists working in this medium, many of whom have informed my fashion collections and curatorial projects.

Photograph by Luis Monteiro. Courtesy Duro Olowu

Courtesy Duro Olowu

Thawley: You touched upon the role of color earlier. Do you ever operate as a colorist, looking at photography when you put together your patterns and your different swatches and fabrics that you’ve created for your fashion line?

Olowu: Absolutely. I have to say that it’s photography and film, and photography is really important. It’s the Technicolor aspect of everything—a kind of faded Technicolor. It’s not jarring. When I design textiles, even if they’re monotone, even if they’re in very vivid colors, the whole idea is that it’s not jarring. It doesn’t make your eyes ache. Because it has to be easy on the eye—and on the heart. It’s a very emotional thing. So people like Joel Meyerowitz, I love.

Like Gordon Parks, I love the way William Eggleston can transform a painful photograph—a clear display of segregation or racism—into an empowering one for the person segregated against because they’re wearing the most beautiful, simple clothing in the most vivid color. It’s a very conscious effort, I think, on the part of the artist. It helps me see how color looks to other people, how color is represented.

I learned very early that after I’ve designed a fabric and I’ve seen the first swatches, when I do the variations or we cut the outfits, I put the different looks together and shoot them. When I see the photographs, I have to say they look like what I designed, but the intensity of the color is a hundred times more. It’s a very empowering, exciting thing. Sometimes it’s black and red or yellow and blue. It’s not necessarily a whole cacophony of print. It could be solid colors, but when you see the luminosity, it reminds me of Luigi Ghirri’s photographs of a veranda, or an umbrella on the seaside, or of a curtain in the front of a mechanic’s shop. When you see your work photographed, you realize how the photograph has made it real to you.

If you really look at a photograph by an artist, there’s something about the way they try to manipulate the color, even if it’s black and white. There’s Barkley L. Hendricks’s photographs. He’s one of the greatest painters ever. But he was also an incredible photographer. There’s a picture of the two women at the airport in mink coats, but also a man in Nigeria in 1978. Hendricks happened to go to FESTAC, the Nigerian arts festival. He just stopped this guy in that fuchsia top and trousers and photographed him. Now, if you look at that fuchsia, I don’t care whether you work with the best silk-dyeing mill, you never imagine that you can get that color. And then, when you look at it in the photograph, I think that is exactly the future that I want. It really helps me see fashion as more than just something flat.

Thawley: Do you take many photos yourself?

Olowu: Well, most of the pictures I put on Instagram that aren’t credited to someone else, they’re my photos. It’s not something that I’ve ever thought I want to pursue as an art. I love taking photos because when I’m taking them, I’m not thinking. I’m just capturing that moment. All my photos on the streets of New York, Dakar, whatever, when I look at them later, I realize I wasn’t as familiar with certain things. That’s why I respect photographers. Because after a while, they somehow manage to sense what’s going on completely in that frame, before they take the picture. Nothing is really left to chance.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”