Introducing

In New Delhi, Bending Facts to Get to the Truth

By restaging scenes of state violence in the city, Vani Bhushan blurs the distinction between history and memory.

Vani Bhushan was thousands of feet in the air when her Yale MFA project began to come together. In a way, the long-haul flight between the United States and India was the perfect time for Bhushan to reflect on her practice developing between two continents. “In those fifteen hours, I started giving structure to what I had known and seen in India and what I had learned existing away from it,” she says. Bhushan grew up in New Delhi, a city that, as India’s capital, has witnessed some of the republic’s most intense political furores, particularly in the past few years. Through extemporaneous, enacted scenes of policemen and protestors in action, her current work, comprising one untitled series and another called Waiting on images that won’t appear, explores the relationship between camera and field, state and citizen, and history and memory.

Famously hostile to its women, Delhi’s landscapes, especially in times of unrest, can thwart their access. “The street does not favor me as it does a man,” Bhushan says. “And I think that that’s where I’m starting from.” This disadvantage might propel a young woman photographer toward elaborate tactics, such as staged reconstructions of past events. Over the last year, Bhushan spent her summer and winter breaks doing precisely this, shooting every day in Delhi, using two different cameras, a large-format 4-by-5 “not commonly seen in India” and a 35mm. She staged locations covered by the international press during the heatwave that wracked India in 2024. The idiosyncratic criterion was a way of asserting control over an “unforgiving” geography. Collaborating with aspiring actors from Delhi’s informal street theater communities, who were largely migrants from smaller towns and villages, she photographed young men playing the roles of the policemen and protestors who could well have been part of, for instance, the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act five years ago.

The nature of the camera influences the choreography and distance between Bhushan and her protagonists; the photographer’s body becomes a focal point. Elaborating on how she set up the shots, Bhushan says, “I photographed while the actors perform the seemingly ‘actual’ event; they do not know when I will choose to make the photograph. I was also often pushed, shoved, and me and my camera hit by lathis during the making of these.”

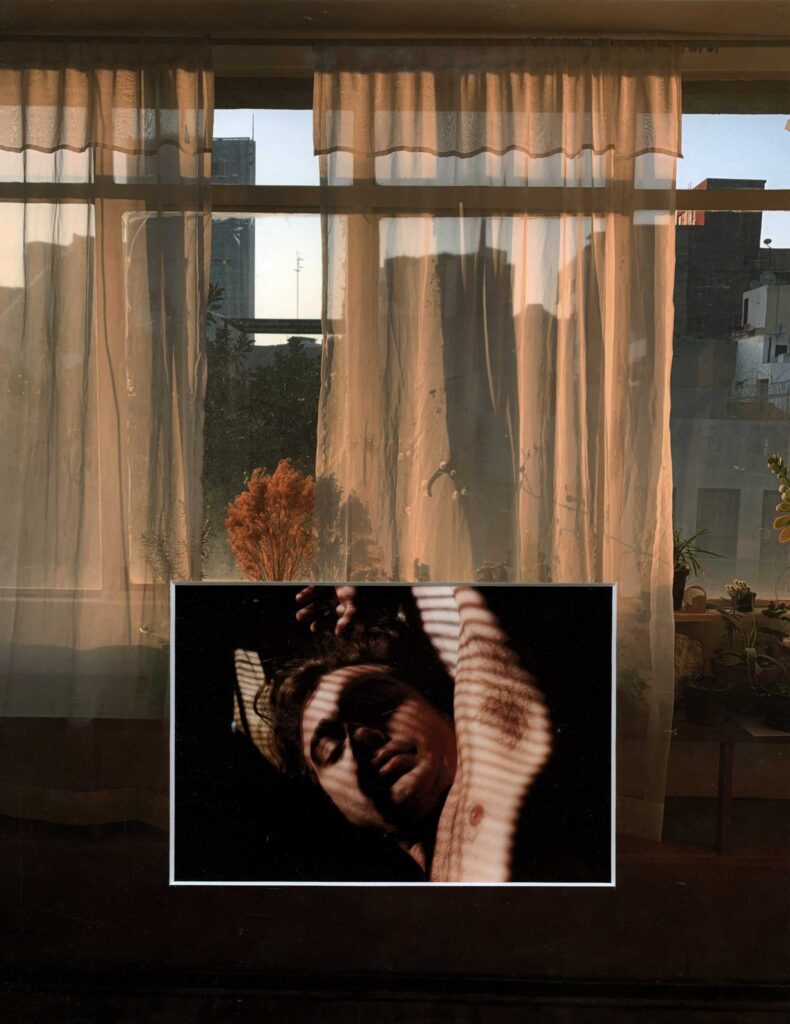

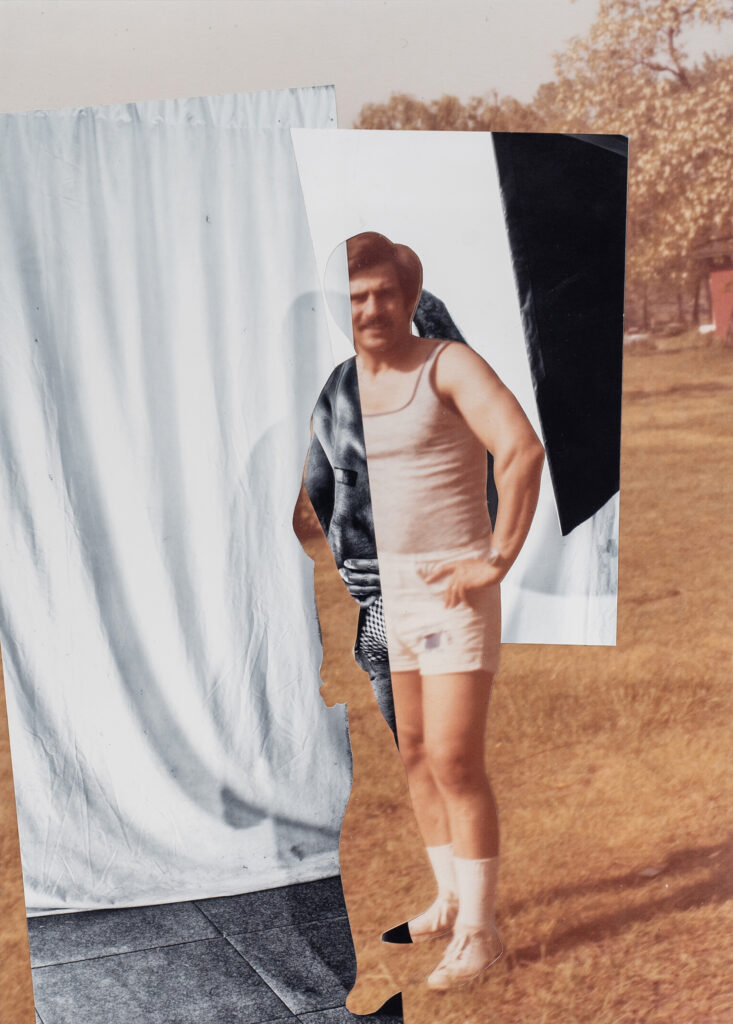

The untitled series, shot with the 4-by-5 camera, depicts the characters of the policemen in medias res at the untended, vaguely industrial, and desolate frontiers of Delhi. Bhushan composed the images without a viewfinder, shooting without seeing. She gave little direction to the participants, because “once the film is in and you’re exposing the negative, you’re not looking at anything. I don’t see what I’m doing as I press the shutter. I am positioning my actors, but they’re not standing still. And standing still is very important to the 4 x 5.” On the other hand, in the series Waiting on images that won’t appear, the fluidity of the 35mm camera places Bhusan—and by extension the viewer—in the thick of what resembles a first-person record of police brutality. Shooting these images, she felt like a photojournalist, “because I’m moving while the performance is happening and there’s multiple times where I have gotten hit because I’m so within the moment.”

The landscape, too, was in conversation with the camera, becoming yet another participant. “I had to wait for the landscape to perform for me,” Bhushan explains. “The dust, for example.” There were no fixed roles—actors played both policemen and protestors depending on the day’s schedule—destabilizing fixed notions of identity over the course of the series. Nor were there scripts or pre-planned scene blocks, leading to Bollywood-inspired improvisations: “You want to let the actor be the actor. What’s really interesting is the take on masculinity when they’re in uniform. I think there’s a shift in power.” In one photograph, a policeman stands arms akimbo in the dust-hazed background, while an out-of-focus colleague prowls towards the camera, once again casting Bhushan in the role of intrepid photojournalist, recalling the risks that chroniclers of state violence often take. “In this emulation of a journalist, that image is the last one before my camera’s taken away from me,” she says. “But in reality, I would never have access to it.”

This play with facticity, an increasingly common mode of image-making in the post-documentary era, runs through Bhushan’s work. A bleak off-highway wide shot, a decrepit airplane, and tear-gas-misted policemen offer clues to an ominous but irrecoverable chain of events. During her darkroom experiments, Bhushan printed these photographs from the untitled series on paper aged in an environmental chamber, bestowing on them an unsettling vintage quality, as though they’d been sourced from a dusty old police file, or perhaps film stills from a defunct studio’s detritus. The ambiguous effect is enhanced by the archival disaster images found in a box at a secondhand market that intersperse the series—the flotsam of what looks like a tram submerged in monsoon deluge and the scene of motorcycle accident. Bearing the stamp of a famous old tabloid’s art department, they intrigued Bhushan, who wondered if they were actual images or if they had been staged.

The instability of truth was inscribed by the camera itself onto Bhushan’s images. In the photographs from Waiting on images that won’t appear, the left quarter of the frame is covered by a black vertical strip, the result of inadvertent shutter drag. The effect gives the sense that the photographer was shooting from behind a screen, her visual field occluded and her vision therefore unreliable. “I don’t like the term half-truth,” she says. “A half is when something is divided equally. The black shroud on the left cannot be equated to the event on the right. They both have separate meanings, but are read as one plane.” Perhaps one way to think about the relationship between the two sections is to compare it to that between object and subject, between history as it happened and as it was experienced, when it becomes memory.

Bhushan considers her work a record of recollections, both unauthorized and official, rather than hard realities. Considering the figure of the photojournalist and the artifice of the archive, she questions the medium’s claims of verisimilitude and the integrity of photography collections. In discussing her work, “truth comes up a lot, document comes up a lot. I think the word ‘document’ is flattening, both formally and conceptually.” Bhushan is interested, instead, in the camera’s ability to reveal truths, citing revelations yielded in the darkroom off the blindly shot 4-by-5 negatives scratched by Delhi’s dust, or the accidental shutter drag of the new 35mm camera. “I learn from the medium when I make the image . . . I think of the photograph as a didactic device.” The word document comes from the Latin docere, to teach. There are lessons in revisiting well-documented narratives of contemporary state violence. Bhushan’s practice reflects on how history (and, indeed, truth), as she puts it, “exists in imagery in one way, and then within memory in another.”

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.