Featured

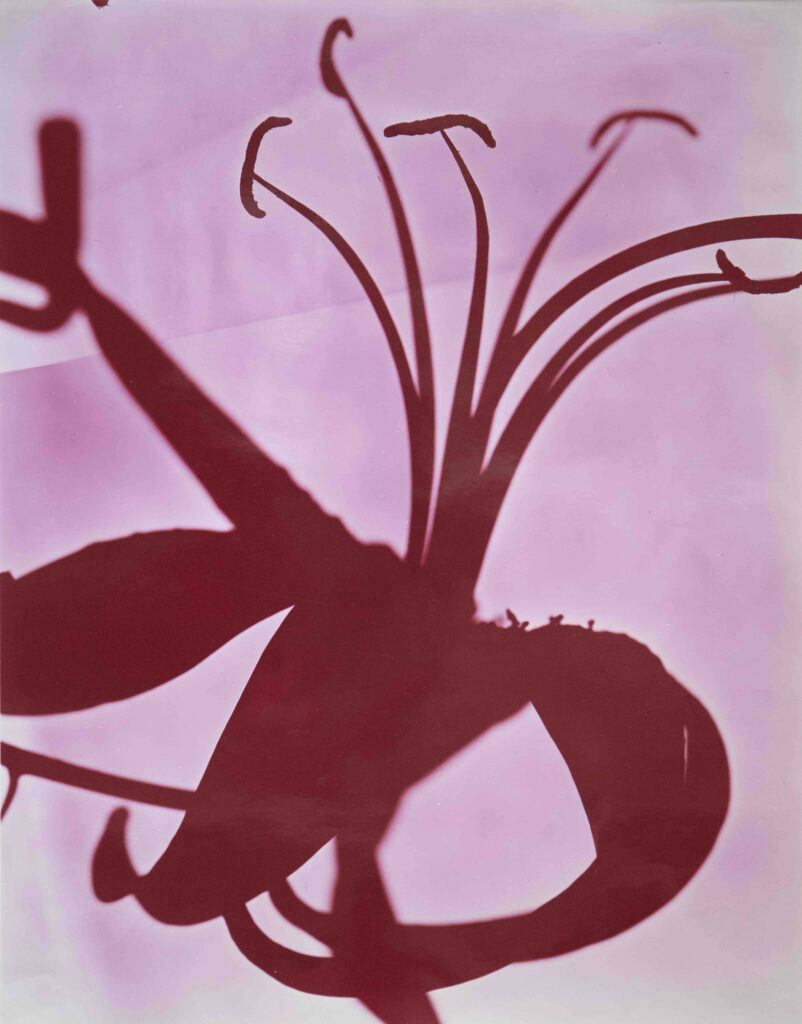

Jade Thiraswas’s Sensitive Chronicle of Pride and Mourning in the American South

For the Thai American photographer, small beauties and unforgiving travesties are all part of what it truly means to live in Louisiana.

There are many signals to the start of spring in southeastern Louisiana. By early March, during a season of festivals and parades, city and country begin to overflow with creeping vegetation, boats leave their docks on the levee to become floating social spaces, clothes get thinner and lighter, mornings and evenings open and close with the thick smell of blooming jasmine. The air, not yet oppressive with humidity, presents opportunities to be outside and in community with others. Crawfish boils, carnivals, krewes, and second lines signal the arrival of a weekend and time in the garden organizing wild plants into submission becomes urgent maintenance work. Suddenly, for a few brief weeks, a region dominated by the tidal forces of water and weather allows human and climate to enact a short, soft truce. Hurricane season remains in the future, leaving just enough room for those of us who live in this challenging place to fall in love with New Orleans anew.

For the photographer Jade Thiraswas, the opportunities provided by the return of spring in Louisiana as explored in her recent series Tiger Balm (2023) are rendered more complex. While dark murky waters, Spanish moss, and the gentle curvatures of the bayous all make appearances, they are not left to their own devices to run wild—something small, but significant interrupts the urge to let Louisiana trade on its usual tricks of unbridled revelry and nature devoid of conflict. Across the series, Thiraswas’s images work to hold the idyllic at bay to provide a foundation for interrogating the many complexities and tensions of life and living in New Orleans as a young woman, as a daughter, as an immigrant.

Thiraswas forms a multivocal, fragmented narrative of life as a Thai American in the South, and the cultural and political entanglements experienced by the many diasporas of immigrants that have settled in the curving crescents of the Mississippi River. “I wanted to take notice of what the American Dream looks like here,” she says, “to see the ways in which public celebration, different forms of pride, and at times, mourning all exist together.” In her community, Southeast Asian and Southeast Cajun cultures share these landscapes and embroider upon one another, moving the photographic tropes and expectations of the American South (and southeastern Louisiana, specifically) into an arrangement of home as inseparable from the effects of colonial violence, precarity, and systemic inequities.

Tiger Balm brings together sequences of landscapes, domestic interiors, and social gatherings taken in and around Thiraswas’s family home in Mandeville, the Tchefuncte River, and across Louisiana’s southeastern river parishes. Scenes of folks of all ethnicities and ages competing in a local crawfish boil, a delicacy beloved in Cajun and Asian communities alike, offer a proposal of difference as integrative and celebratory. Other images do not resonate as symmetrically: a wide shot of young high school baseball players warmed by sweat, sunset, and fairground lights ambling toward the camera tells a story of white male youth’s uncertain swagger; an image of an older Southeast Asian woman, resplendently dressed in the glowing golds and yellows of traditional Cambodian garb, turns away from our gaze as if holding onto or protecting something for herself. An abandoned boat half sinking in muddy waters, lost to time and neglect, rubs up against an image of a small black sign celebrating private property rights and warning against trespassing, its angry insistence nearly defeated by glossy green foliage. Nighttime images cover the watery environs in a flat, thick darkness. Across this series, Thiraswas reminds us that the landscape is not so smoothly or equitably traversed, that there are quiet, dark things lurking.

Thiraswas’s portraits of her father and the interior rooms of her parents’ home are striking for their emotion. At ease in front of his daughter’s camera, Thiraswas’s father, Paul, tends lovingly to his outdoor arboretum and tinkers with a vintage car in his garage—familiar activities of an older, Southeast Asian patriarch committed to caretaking and industriousness. This cycle of spring-cleaning aches against the tender images of his late son Ty’s bedroom and personal space. Ty was lost to the opioid epidemic in 2021, and a table filled with action figures, high school graduation ephemera, burnt CDs, and childhood photographs seizes upon the bounty and possibilities inherent in a life cut short and the individual tragedies experienced by so many—too many—families living, working, surviving, and making do far away from another place. For Thiraswas, these small beauties and unforgiving travesties are all part of what it truly means to live here in Louisiana—to acknowledge the jasmine blooming despite or alongside so much lack and loss.

Jade Thiraswas’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera.