Portfolios

Stephanie Syjuco Confronts the Power of the Archive

Syjuco’s rigorous photographs show how interrogating institutional collections can be a potent tool in decolonizing American history.

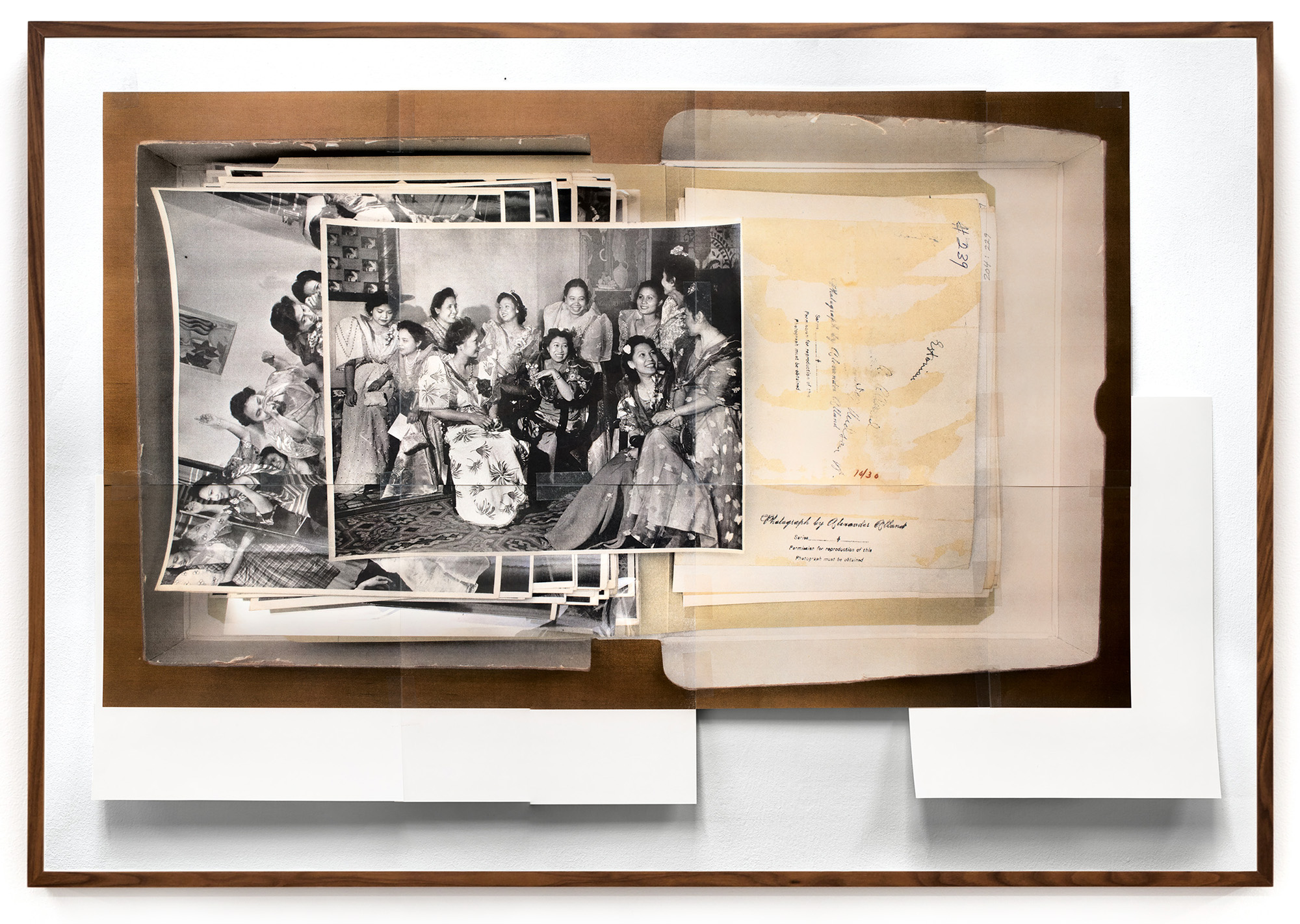

During her residency at the archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, in Washington, D.C., the Oakland-based artist Stephanie Syjuco sifted through material, tracing ideas of American empire, memory, and citizenship. The records she uncovered range from bureaucratic records of the Ohio chapter of the Ku Klux Klan to an image of Filipino women from the photographer Alexander Alland’s project American Counterpoint, which sought to document ethnic and racial groups in America and was published as a book in 1943.

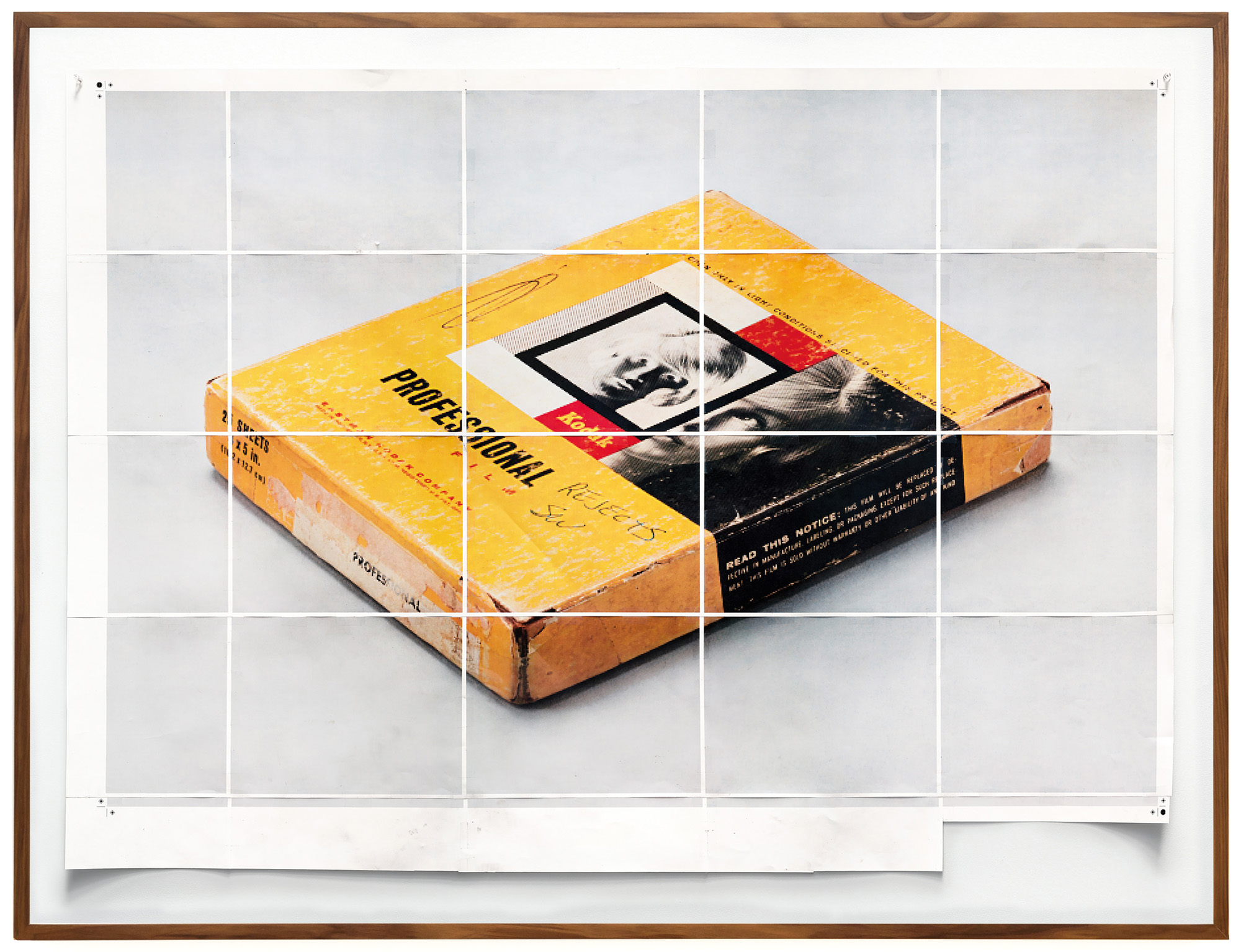

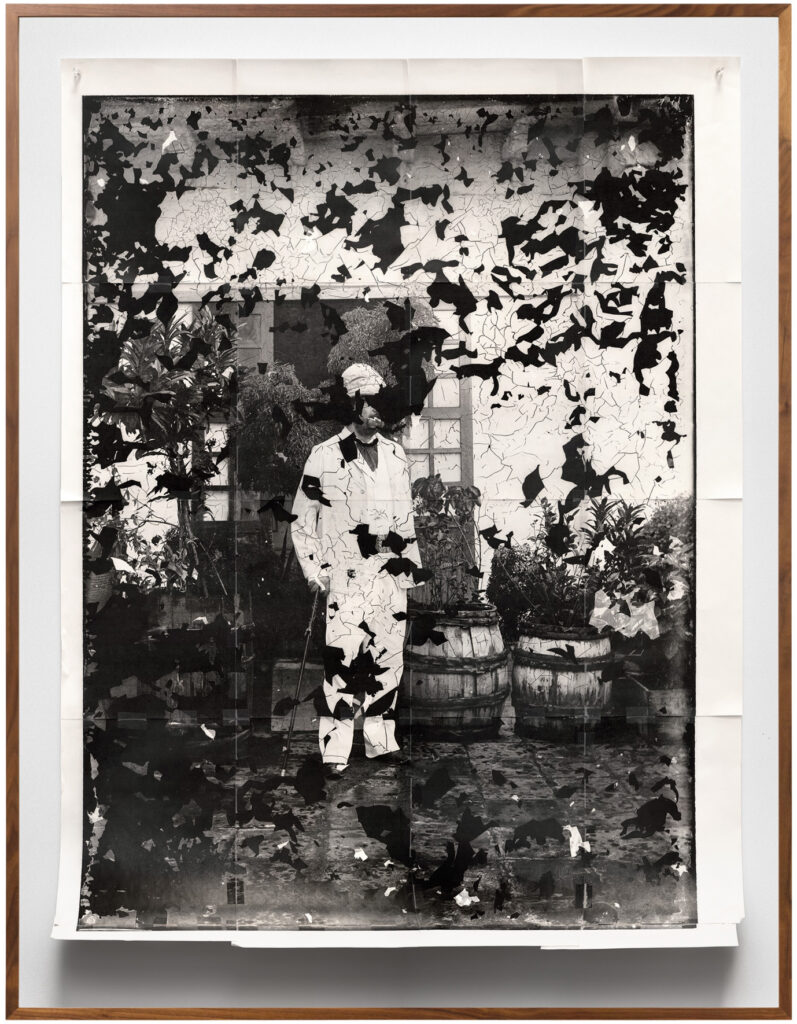

Working in the archive, without access to studio equipment, Syjuco first made images of documents and objects at low resolution. She then printed them in sections on office paper, taped the sheets together to reconstruct the original image, and rephotographed the collages in high resolution. In one image, Syjuco shows us a closed Kodak photo-paper box. Its yellow cover features the brand’s trademark portrait of a white woman with coiffed blond hair, and a handwritten annotation reads “Rejects.” Only the image title indicates that the box belongs to the archive of Henry Clay Anderson, a Black photographer who documented segregated life in Greenville, South Carolina, during the mid-twentieth century. While the final image is crisp and smooth, the visible evidence of its assembly reveals layers of labor and scrutiny, which point to the constructed nature of the archive and the power dynamics that underpin it.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

For her project Image Trafficking, Syjuco was invited to respond to the vast collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. The photograph that closes this portfolio shows her studio pinboard, with reference images of reference images layered over one another—an expansive collage of the collection in all its complicated beauty and violence. An image of a Native person scalping a white woman is abstracted and obscured by overlaid archival documents; another depicts a reconstructed image of a milky-white-crowned bust of a woman, made in 1860 by Hiram Powers, simply titled America.

In a photograph called Still Life, a bright green backdrop highlights a mise-en-scène of museological props: various kinds of tape, a photo color chart, a knife triumphantly skewering a foam wedge. Here, “the ‘peripherals’ all of a sudden became the subject matter,” as Syjuco says, making visible the museum’s tools for maintaining, repairing, or documenting the items it holds in trust. Syjuco’s rigorous photographs show us that collections themselves may be the most powerful tools we have to dismantle the systems that built them. They remind us to look carefully and slowly, to work to unravel the threads of history within and among the things we’ve gathered—and, in the process, to find new stories.

Studio production view of reference images for the exhibition MATRIX 190: Stephanie Syjuco: Image Trafficking, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, 2022

All photographs courtesy the artist; Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco; and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”