Interviews

The Lives of Coreen Simpson

For five decades, the photographer and jewelry designer has chronicled hip-hop, fashion, and New York’s cultural scene with unparalleled style.

Coreen Simpson—photographer, writer, jeweler—has done it all.

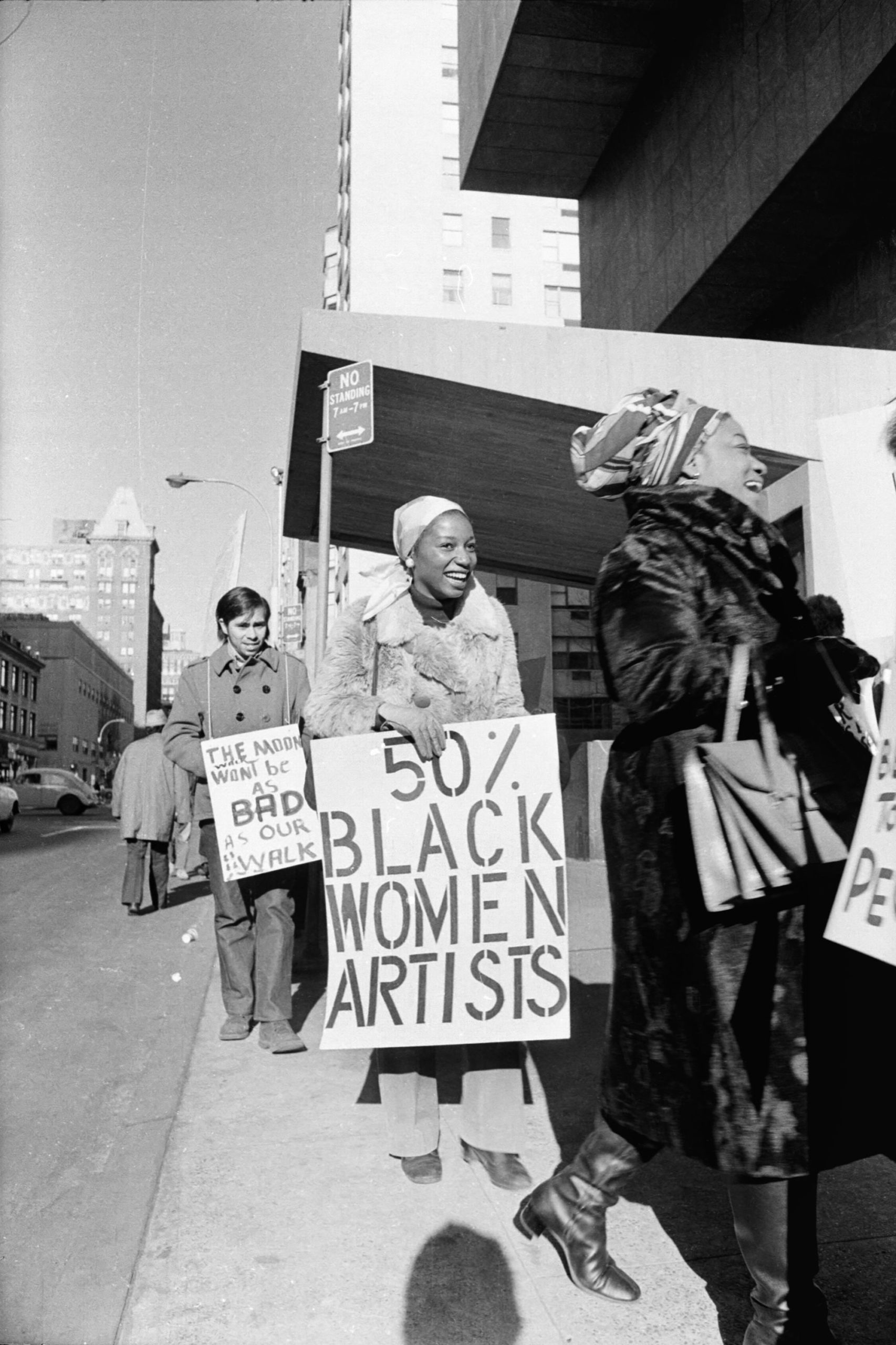

Working for publications such as Essence, Unique New York, and The Village Voice, from the late 1970s onward, Simpson covered New York’s art and fashion scenes, producing portraits of a wide range of Black artists, literary figures, and celebrities. Her iconic jewelry, the Black Cameo, has been worn by everyone from the model Iman to civil-rights leader Rosa Parks.

The second title in Aperture’s Vision & Justice Book Series, created and coedited by Drs. Sarah Lewis, Leigh Raiford, and Deborah Willis, Coreen Simpson: A Monograph showcases the luminous, wide-ranging contributions of an essential artist. This long-awaited volume, Simpson’s first, features her celebrated B-Boys series—portraits of young people coming of age during the early years of hip-hop—as well as her experiments with collage and other formal interventions. An assortment of essays and an extended interview offer powerful reflections on Simpson’s unique blend of portraiture, sartorial politics, and her riveting story of an intrepid life in journalism, art, and fashion. Below, read a conversation from the volume between Simpson and Willis.

Deborah Willis: Thank you for this opportunity to discuss your work for our Vision & Justice project as we remember the impact photography had on our lives as young girls until now. I recall us living as neighbors on the Upper West Side in the 1980s when we would run into each other going to events, shopping, and participating fully in the arts movements around New York. We always respected each other and our work.

I also remember the time we took our first trip together to Detroit, Michigan, for an exhibition I curated in 1982 with Dan Dawson, Photography: Image and Imagination, held at the Jazzonia Gallery. George N’Namdi and Rosalind Reed were the owners. It was a long road trip, but it was an exciting time as we began to reshape ideas about photography and its meaning to social justice, migration, and art. The photographers included Joan Byrd, Dawoud Bey, Albert Chong, Frank Stewart, Adger Cowans, Jules Allen, Bob Fletcher, and John Pinderhughes, naming only a few of the twenty artists. We were committed to bringing diverse stories to the exhibition. I remember with great fondness being inspired by your work because they were large-scale images of women, strikingly beautiful, and you painted on the photographs.

I also will never forget the time we spent on the 1989 artists’ trip that included David Avalos and Yong Soon Min, among many other artists, to Palestine, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Gaza, particularly the difficult moments when the men didn’t understand our focus as women. Geno Rodriguez, then director of the Alternative Museum in New York, organized it with the invitation of Palestinian and Israeli artists. We visited these and other cities for the exhibition Occupation and Resistance: American Impressions of the Intifada, which was on display at the Alternative Museum, in 1990. Some of the people in the group challenged us because we took photographs of items and objects that were of interest to us: We focused our cameras on the land, interiors of homes, and I searched for Black Palestinians and children in hospitals. Some thought our work was apolitical because we were looking at the land in a totally different way. We saw Molotov cocktails on window ledges and photographed them.

Coreen Simpson: On that trip, we thought as mothers because we were also mothers. We saw how the Palestinian women lived under adversity and yet kept a home filled with color, and domesticity, despite lack of finances. This was truly inspiring.

Willis: In New York, we spent days and nights attending openings in the Village and on the West Side, and, of course, at Just Above Midtown gallery. The 1980s were, indeed, an exciting time, especially for Black artists. We were all together—photographers, painters, sculptors, writers, performance artists, musicians. Getting to know you affirmed my interest in imagining a biographical narrative in your portraits.

Simpson: That was a great time.

Willis: It was.

Simpson: We didn’t know that we were living in such a great time. We were just going with the flow.

Willis: It was normal. Everything was just love.

Simpson: That’s right.

Willis: You were recognized as a photographer and jewelry designer. If you agree that is the case, and I’m leaving it to you to decide if it is, what would you say has been your lifelong quest?

Simpson: I think my quest was to really be independent and just to do something that I would enjoy. I worked as an executive secretary. I always had good jobs. But I was tired of that. And I realized one day—Coreen, you’ve got to get a career, this is not working.

So, I interviewed myself: “Well, what do you like to do?” I was freelancing, writing little lifestyle articles for Unique NY and stuff like that. But I wanted to do something that I enjoyed doing, where I could be free to do what I wanted to do. That is my lifelong quest. I haven’t worked for anybody in many, many years. I can’t believe I pulled that off.

Willis: How did your interest in visual culture and photography begin?

Simpson: I was doing freelance writing, and I didn’t like the photographs that people were sending in or taking of my subjects. I just thought, My articles would look better if I could photograph the way I see my subjects. So when I told Vy Higginsen that I wanted to take my own pictures, she replied, “We didn’t know you took photographs.” I called up Walter Johnson, who became one of my mentors, and I said, “Show me how to use this 35mm camera.” He came over, loaned me a Canon 35mm, and showed me how to use the light meter inside the camera. That’s how I started, just like that. And then I liked taking pictures better than writing. To me, it was more interesting.

Willis: Tell us more about Vy Higginsen.

Simpson: Vy Higginsen was a Broadway producer at this point. But she was a very well-known New York DJ on the radio, with Frankie Crocker on WBLS. And she had a magazine called Unique NY. I loved the magazine. It was a long vertical magazine, very thin, and it had little articles about the uniqueness of New York.

I called her up one day. I didn’t even know Vy at the time. I said, “I have an idea for an article.” Because I was dating a bartender at the time—he was an actor, a very handsome guy—I told her, “I’ve met a lot of bartenders. Why don’t you do an article about bartenders? I could do it. I could interview four bartenders for you.” So she said, “Oh, that sounds great. Can you make it three typewritten pages?” So that’s how I started writing for her. That’s when I decided I didn’t like the photographs. The next time they called me to do an article, I told them, “I want to take the pictures; I will do the article only if you use my photographs.” That’s how I got started.

Willis: Sounds like you created your first photographic assignment, do you agree?

Simpson: Yes. That taught me a lesson. Don’t wait for anyone to give you an assignment. Never wait. Just do what you want to do, then sell it. That’s what I’ve always done.

Willis: Did you continue writing?

Simpson: A little bit here and there. The Village Voice asked me to do little things.

Willis: But you did a lot of lifestyle and fashion stories?

Simpson: Style things and lifestyle pieces. I’m very curious about how people live.

Willis: But during that time, did the photography of the civil rights movement and the activists from the Black Arts movement change your perception of how you wanted to see Black people in print? Your portraits reveal identities that had not been seen.

Simpson: I just didn’t want to see Black people all downtrodden. I was very inspired by Richard Avedon when I saw his work, his fabulous work. He made a big impression on me. I said, I want to do this with Black people. Because that’s how I always saw my own people. I was raised in a foster home, two foster homes, but really there was the main one later on that raised us. I always saw Black people, my people, as heroic in many ways. The women that I met were fabulous, and I just always wanted to take pictures to show the beauty, the grace, the dignity. I always wanted to put that in my pictures.

Willis: You described in an interview recently that you sat on the stoop in Brooklyn when your mother combed your hair.

Simpson: Yes.

Willis: As if the stoop was your auditorium seating.

Simpson: It was like the theater. And it was up a little high. She would part my hair. And other neighbors would sit on the stoop in Brooklyn. As a young kid, I would see these fabulous people walking by, dressed so beautifully. I said, Oh, did I just see that? I saw a man one time in an orange suit. I mean, can you imagine?

Willis: You still remember that.

Simpson: I still remember that, and the swagger. I just wanted to capture it. But I didn’t know how because I knew nothing about photography. I have no pictures of myself as a baby, as a young kid, my brother and I—because we were in an orphanage and then in foster homes. So the camera was very important to me. I would love to see a picture of my parents, my biological parents. I have none. So the value of the photograph . . . I always think it’s so important, the document that you have. And I wish I had that.

Willis: I love that story of thinking about how you viewed the world and your desire to document and change the visual experience of how Black people have been portrayed. What other photographers influenced you?

Simpson: Gordon Parks. James Van Der Zee, of course.

When I was studying at the Studio Museum, in Frank Stewart’s darkroom classes, he would always come to me and say, “Oh, have you seen this book?” He did it so casually. He planted the seed in me that we must study the history of what we’re doing. Then I learned about Baron de Meyer, and I loved the lighting techniques. Cartier-Bresson. All those I learned. And I started collecting my own books.

I have quite a big library of photobooks.

Willis: It’s amazing, because when I think of your work, I always connected it to Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Simpson: Capturing the moment!

Willis: Moments at night.

Simpson: Oh, I love it.

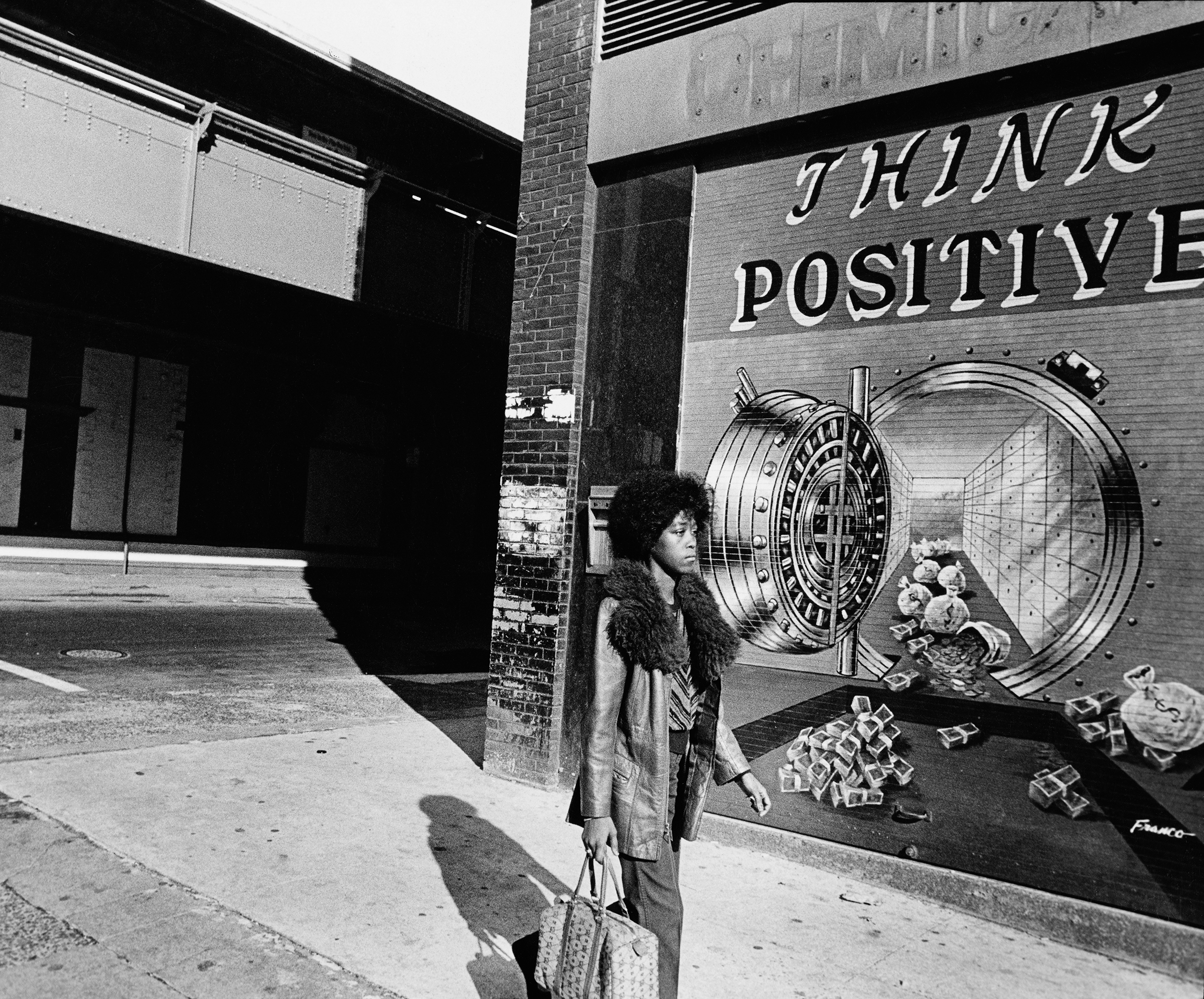

Willis: How to rethink joy and pleasure. It’s not just everyday night moments, but the way that you visualize how women dress. Can you talk about how you began to think about fashion and photography?

Simpson: Well, fashion has always been something I was interested in. I remember as a teenager, I worked for a camera store, never realizing one day I would be a photographer. I never had a really good wardrobe. So I saved my money and bought clothes for my junior year. No one really paid me any attention until I had these nice clothes that I saved for. I remember going out one day in my neighborhood, and I had a fake pink leather jacket on, and I just remember how people were looking at me. I thought, Oh, that’s powerful. Fashion is a powerful thing.

Willis: What made you decide to take a class at the Studio Museum in Harlem?

Simpson: Because I was taking pictures, taking them to the lab, but I didn’t know how to develop my pictures. Frank was teaching that class in the late ’70s. Carrie Mae Weems was in my class. Isn’t that amazing?

Willis: In 1970, I took my first class at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and I studied with the filmmaker Randy Abbott. He led filmmaking and editing workshops there, and Toni Cade Bambara was one of the student-participants at Studio then. I wanted to make films. Studio Museum has been a core for many of us. Did you have any early exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem during that time?

Simpson: I had a show there in the late 1970s with John Pinderhughes, a two-person show, Encounters. I remember showing at the Urban League’s Gallery 62. They gave me a one-woman show.

Willis: I remember that show and another exhibition Photographs: Coreen Simpson and Jacqueline LaVetta Patten (1980). The Urban League supported artists by hosting exhibitions in the lobby gallery.

Simpson: Yeah. So long ago. I had those big photographs up. I showed the Nitebirds/Nightlife because I liked a lot of night stuff, parties and stuff like that. I blew up pictures of the characters that I met at night.

Willis: Where did you go out then?

Simpson: All those clubs. I can’t even remember. The Mudd Club was one. Different little clubs. When I would go to the clubs, I would see a lot of different people and just click, click, click, click, you know.

Willis: One of the points of your work is that directness of the gaze. People posing, wanting to be seen, and you see them!

Simpson: I always tell people to look right in the camera lens. Like when I did the B-Boys series in the 1980s, I would just pull people off to the side that I thought looked fabulous and put them into the studio that I set up. I always had to give them a little pep talk. I would say, “You look so fantastic and I want to photograph you,” then very briefly tell them what I’m trying to do, and have them sign releases. I would tell them that this is for posterity.

Willis: Why the title B-Boys? There are girls in there as well.

Simpson: Well, the girls came later. I was really focusing on the hip-hop scene, the breakdancers. That’s why I called them B-Boys. I saw a guy on the train. I gave him my card and said, “Come to my apartment,” because I wanted to photograph him. Richard. That was my first B-boy. Then he brought his friend with him, and he was gorgeous.

I showed the pictures to my daughter and asked, “Where do I find more?” She said, “Oh, go to the Roxy, Mommy, because that’s where they hang out—at the Roxy.” I went to the owner of the club and told him what I was trying to do. “I want to do this as a project. Would you help me do this as a project? Can I set up a studio here?” They went along with it. Everybody liked to be photographed. People go out at night, and they look great. They want to be documented.

Willis: You had the camera and the backdrop, and the studio was set up at the club?

Simpson: I had a big backdrop for the portraits that I did at the Roxy. The Roxy was huge. So they gave me a space, and I just put the backdrop up real quick, the lights and everything, the tripod and all that. But people like that attention. So I had no problem. And then a man came over to me one day, and he said, “These photographs are going to be very important one day.” He told me that. This was the early part of hip-hop, and I wasn’t really that interested in the music. I was more interested in the style. I like jazz.

Willis: I love how some of the kids use style from the ’50s in terms of dress.

Simpson: They had their own unique style.

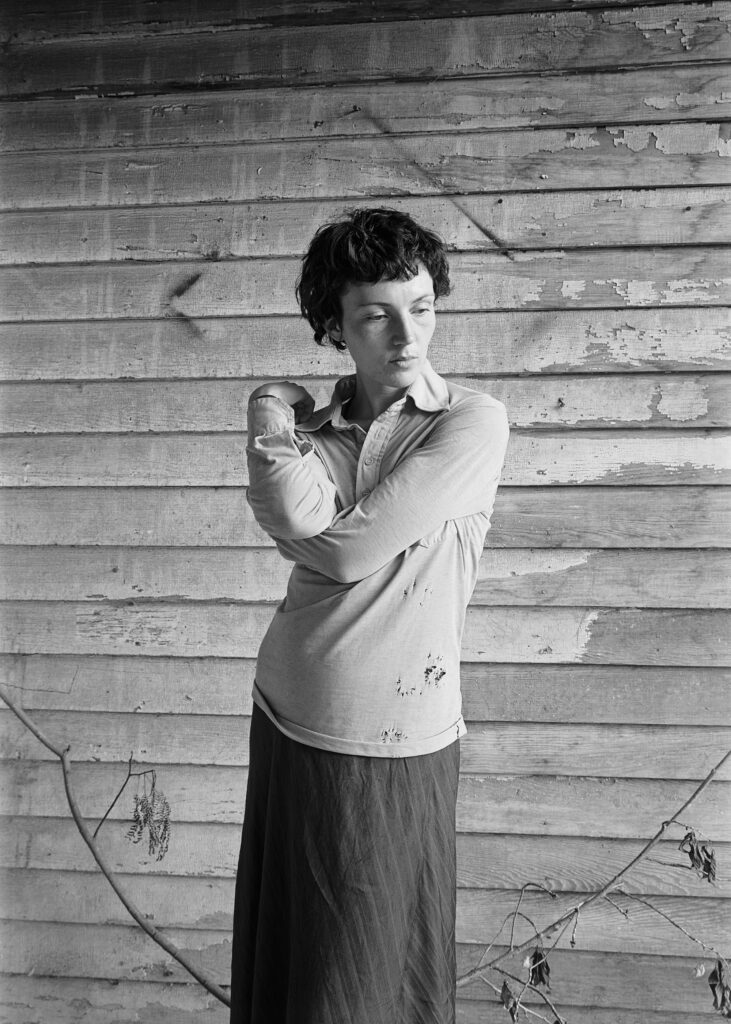

Willis: I see your portraits as stories. They’re storytelling in the most profound ways. It is fascinating that you moved toward enhancing your stories, from direct portraits to collage work. What led you to enhance the images?

Simpson: In the early 1990s, I wanted to do some new work, and I was looking at old photographs in my archives, just looking through things. Some were extras from test prints. They weren’t the prints that I really liked because it takes a while to get the print that you like when you’re printing in the darkroom. I had kept the test prints, and then I wondered, What am I going to do with them? So I began to fool around. At one time, I was doing actual collages. I got very caught up in it.

As a photographer, you want your own language. And it took me years to come to my own language. When I was fooling around with those test prints, little did I know I was creating my own language with the AboutFace series (1991–ongoing). I was just having a little fun. I think I wasn’t feeling so good at one time, maybe it was the wintertime, and I wanted to photograph, but I didn’t want to go out, or I couldn’t go out. So I said, Well, I’ll create a new body of work—I’ll do some collages with these test prints.

Willis: Did you look at Romare Bearden, at his collages as inspiration?

Simpson: Of course. But his were more stories. They were linear.

Coreen Simpson: A Monograph

65.00

$65.00Add to cart

Willis: And your collages are from your own photographs.

Simpson: Yes.

Willis: So that detail that you’re exploring, like the image with the clock that you made in the 1990s. What does that mean when we think about those braids?

Simpson: I’ll let you think about what it means. It just worked.

Willis: Because it became timeless. Braids have become timeless in discussions about Black women and hair.

Simpson: The original picture is of my godchild Alva. Later, it was published in The Village Voice when Lisa Jones wrote an article on Black hair, and they used that picture to illustrate what she was talking about. Then for the collage, I used one of those test prints.

I cut the head out, and I just would go through fashion magazines and pull out anything that interested me. I laid on the clock, and I said, “Oh, I like that,” and I rephotographed the photograph. Because we didn’t have Photoshop then and all that.

Willis: One can see the layers that you created by hand and the shadow within the collages. With the color photographs in Sky Portraits from the early 1980s, when did you decide you wanted to begin experimenting with adding texture, color, or sparkles?

Simpson: That was just an experiment. But I did like painting on the color photographs because of the saturation. When I would get a print back from the lab, I might say, That watermelon isn’t red enough; that watermelon should be red. So I would take the fingernail polish and color it in.

Willis: As you said, you were creating your own language. But then, these were also becoming ways to create new identities. That’s something that you explored, in my mind, in the work that you were making—that these people were reimagining their identities, and they had a little sparkle in them—just to have those moments.

Simpson: Dazzle, yes.

Willis: To me, they were dazzling.

Simpson: That’s why I called the one series Nitebirds. Birds of the night.

Willis: Here again, you’re creating your own terminology, your own language in that work.

When I think about your role during that era, a creative time for us, you were acknowledging that we walk the talk of self and beauty. That’s something I was encouraged by when looking at your work. You transformed the Black body, you posed new questions. Like your directing of the poses in the B-Boys series: You tell them to turn away from the camera, but at the same time, you are seeing them—because they’ve not been seen. These are kids who have struggled but they found a way to shine. How did they respond to you?

Simpson: They responded very well. I always want people to say, “Damn, where’s Coreen going?” It’s an adventure. The camera gave me license to see the world. When I have my camera with me, I’m not afraid of anybody. I always feel like I can just do anything if I have my camera with me.

Willis: The camera gave you security.

Simpson: It did. I love that feeling.

Willis: What I see in the photographs that you create is not only that you’re helping them create their identity, but you are documenting their identity. I think about identity and about how art and social practice come hand in hand, specifically with your photographs, jewelry, and cameos. Did the Black Cameo start with a photograph? Or with a drawing?

Simpson: I had never even thought of doing a cameo until one of my clients asked. She was editor in chief of a magazine. It was a white magazine, and she was a Black woman. One day she asked me, “Oh, Chanel came out with a new cameo. I love it. But I don’t feel like I should wear a cameo of a white woman, Coreen. Can you make a cameo for me?” I told her, “I don’t make cameos. But I’ll look around and see if I can find one for you.” I went to the diamond district, and no one had a cameo of a Black woman. They were all white cameos. Then I asked a lot of Black women, elderly Black women, and they said, “No, I never saw it.” Although there were Black cameos in Europe, of course. There are famous ones, including cameo habillé. I went to the library to do research and saw some from the 1800s. And they were beautiful. But I wanted to do a modern cameo of a modern Black woman.

Willis: Whose profile is that?

Simpson: I found a model maker, a Black model maker, and I showed him a picture of one of my subjects. I said, “I want it to look like her profile.” Jewelry is very similar to photography, in a way. It’s a visual. That’s all.

When my business took off, I had a studio on Thirty-Seventh Street off Fifth Avenue, and a Black woman wrote to me and asked, “Can you make an angel for me? A little Black angel pin? I see all these little white angels. But I want a Black angel.” And

I sat down with my factory, and we designed the Black Angel pin. That was a phenomenal success.

Willis: That’s amazing. You and I have similar interests, because that’s also why I like going to Florence, Italy, looking for those cameos. I remember my mother had one of those Black cameos that they had. They had a lot of lamps and figurines that focused on the Black female body.

Simpson: Well, when George Mingo went to Italy, he went to visit David Hammons. David won the Prix de Rome and invited George to visit him. I said, “I want a cameo that’s a Black woman.” I still have it, but it’s not a Black woman. It’s a white woman in black. That’s what I was always seeing.

Willis: Yes. And that’s the same thing that my mom had. It wasn’t a Black woman. It was in black.

Simpson: So when I was creating the cameo, I was doing well financially, so I went to a scarf company, one of the major scarf companies, and told them I wanted to do a scarf like an Hermès scarf but for Black women. I designed the scarf for the Avon company. They sat me down with their designer, and I would tell them: “I want it like this.” I designed umbrellas, jewelry. I did a cameo for Avon that was different than mine. That was their cameo. They signed me and Elizabeth Taylor at the same time. They had an Elizabeth Taylor jewelry collection, and they had the Coreen Simpson Regal Beauty Collection.

Willis: I was just thinking about Avon when we were kids, because my mom had a beauty shop, as you know, and we grew up in the beauty shop. Women would come in, and they’d pay Mom. So I’m thinking about how entrepreneurial women were during that time, in the 1950s, during the civil rights and human rights activist period.

Simpson: Right.

Willis: But beauty was consistent.

Simpson: Always.

Willis: Always consistent. And I see that’s something that has been consistent with your work. Hank [Deborah Willis’s son, the artist Hank Willis Thomas] has been creating public monuments, and I see that you’re also creating public monuments with your jewelry in a way.

Simpson: It’s so funny. I was talking to Lorna Simpson several years ago, and she gave me a really big compliment. She said, “Coreen, your photographs. . . . You have your photography. But you created that cameo. I see it all over.” But you know what? I always wanted to make money aside from photography. Jewelry sustained my photography, because I could always buy what I wanted to buy. I didn’t have to go get a grant or something like that. I have to always give the jewelry business a big thank you because it underwrote my photography. Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe [the photographer] told me, “I saw you in The New York Times when you first came out with that cameo.” I don’t know if she knew I was doing jewelry. But she saw that, and she was very impressed.

Willis: That’s what I mean. You have created a monument.

Simpson: It was totally unplanned.

Willis: But that’s how most things are. I see pride in the photographs of the people who have worn your jewelry, like Celia Cruz.

Simpson: Yes. She loved it. Her hairdresser was a friend of mine, Ruth Sanchez. I was doing these sparkly eyeglasses. I was selling them. I told the company, “I want you to design it like this for me.” I did a pair of leopard sunglasses, all crystal. I showed it to Ruth.

She said, “I got to have this for Celia. Celia is going to really love this.” And when she got it, Celia went crazy. Then she asked, “Well, what else do you do?” That’s how I met Celia Cruz. People couldn’t believe that she was at my apartment. She came with her husband. I went to her house. She was fabulous. She wore my jewelry on a couple of her album covers.

Willis: Thinking about your earlier mention that you don’t have photographs of your birth parents, do you think this shaped your work in any way, specifically of photographing younger people? Do you think that has any kind of silent message, why you want to make sure some of these younger people see themselves?

Simpson: When I’m taking their picture, I’m thinking, I wish I had had my picture taken when I was growing up. Although I did have a beautiful picture from when someone took me and my brother to get our picture taken. I love that picture. But that’s the earliest.

Willis: But that’s the love I see in the photographs you’re making. I see a sense of reflection.

Simpson: I’m glad you see that.

Willis: That’s what I see with the young people that you’ve photographed over time. Yes, the breakdancing, the B-boys. But the way that they look at you, the way they look at the camera and they see you past the camera, they see us today. I just get chills when I think about it.

You traveled to Europe and the Middle East during your early years. I’m curious how those experiences influenced you?

Simpson: I had a job at a marketing company on Madison Avenue called Patents International Affiliates. A small Iranian company. They were all preparing to go to Iran for a marketing convention or something. I didn’t think I was going, but the president that I was working for, I was his assistant, he said, “Coreen, you have a passport? You’re coming with us.” I was like, “Oh my God, I never would imagine . . .”

Willis: And you already had your passport, so you were ready.

Simpson: The shah of Iran was still in power then. That’s how long ago it was. And after I left, that’s when he was toppled. We were all invited to a nightclub, which I think was owned by one of his brothers. It was called La Cheminée. I don’t know how I remember that club. It was fabulous. You know, Iranians, they were in the oil business, and the people that worked with my company at the time were very, very wealthy. I met so many Arab princes that were there. It was a conference of the Arab Emirates, formerly the small Trucial States, Dubai and all, and they were all in their long, fabulous robes. It was such a fabulous experience. But I wasn’t even a photographer then.

Willis: But did seeing those robes affect some of the things that you experienced when you began covering fashion?

Simpson: Oh, it was so beautiful and inspiring. But I wasn’t even thinking of being a photographer then. I was a young working woman. My kids were little at the time, like five or six or something, and my mother kept them while I was in Iran for a month.

Willis: Tell us about the photographer Bill Cunningham guiding you through the fashion world.

Simpson: I met Bill Cunningham because he covered the collections, and he was one of the star photographers. Everyone respected Bill Cunningham so much. In New York, I would always see him on his bicycle covering his street fashion stuff, and he would say, “Come here, child. Stand over there.” So he photographed me and put me in The New York Times a couple of times. I got to be friends with Bill. When I went to Paris, they were kicking my ass, all the photographers. First of all, there were very few women. There might have been two or three women at the most. And there were so many men, and they would always push me out of the way. I would be too far back. Because at that time, you could sit on the runway. They don’t do that anymore. That was the best. When the women would walk by, you could feel the fabric. That’s how close you were to the models. It was so fabulous. But I could never get to the runway. And Bill saw that I was struggling. He reached out to me and extended his arm and pushed me forward. No one ever bothered me after that.

Willis: You remind the world about Black beauty, and what it means to walk out of the house feeling that you’ve fashioned yourself. The idea of self-fashioning was important, from slavery to the present. So when I share your work, when I give my talks, when I think about your practice in the art, I acknowledge that you are always thinking about social justice. Social justice has many frames of entry, forms of entry. You have created something that I really appreciate—the love and respect that you show to us.

Simpson: I see that we are kings and queens. So with my photographs, I want to show the royalty that I see in Black people—and other people too. I want to show the regalness. That’s what’s behind what I’m doing.

This interview originally appeared in Coreen Simpson: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2025).