Portfolio Prize

Vân-Nhi Nguyen’s Bold Perspective on the Lives of Young People in Vietnam

Winner of the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, Nguyen casts an intimate gaze upon a generation confronting historical stereotypes.

A young woman sits on a plastic-covered bed in a cheap motel room. She is dressed without pageantry or occasion, in a black tank top and a pair of shorts. A small tattoo is visible on the inside of her elbow. She is barefoot. Her gaze is one of neither confrontation nor seduction. “See me as I am,” she seems to be saying. “Look at me as I look at you.” Behind her, a poster depicting a flat, computer-rendered landscape of a beach is tacked to the wall. This could be Vietnam, but it could also be anywhere tropical.

What does it mean to grow up in a country violently marked by colonization and war? For Vân-Nhi Nguyen, the twenty-three-year-old Vietnamese photographer who took the untitled image as part of her 2022 series As You Grow Older, it is a disorientating experience, one that overwhelms her emotionally.

“Our history has been wiped clean every single time from thousands of years of colonization,” she told me in a recent conversation. “It strips us of our identity so that, even now, young Vietnamese people don’t even know who they are to begin with, to even tell a story. When you actually look at the history of Vietnamese people, we didn’t really gain any sense of our own identity until our independence in 1975, which was forty years ago. That’s still within a human’s lifetime.”

Nguyen’s relationship to photography has been complicated. Initially, art was more a means to escape a conventional life and less a way to express herself. “Art, in general,” says Nguyen, “is not something too important to public education in Vietnam. I think it’s fair to say that people need to stay alive first. Not just in Vietnam, but, typically, it’s understandable that people can’t look for anything else if their stomach is empty or their beer is not cold.”

Under Nguyen’s lens, the flattening stereotypes of Vietnamese culture are never present, even if she is perfectly aware of them.

At sixteen, she began taking photographs, and soon, while in college, found a place for herself with commercial and fashion-oriented work. But Nguyen eventually came to see that this type of image making was essentially meaningless. She was equally unimpressed with the clout that the camera lent her socially, and, in a radical gesture, she put it down when she was twenty and stopped producing altogether for two years. “Photography became to me something so shallow and so superficial,” Nguyen says. “I hated the emptiness of images I saw scrolling Instagram, and I hated the cleanliness of the fashion images in magazines. Everything was too sterile and dishonest.”

That time was a fallow period for Nguyen, who spent it looking at photography books, studying not only her peers but those who came before her. One of her biggest influences is the photographer Deana Lawson, whose portraits of Black American men and women, often at home, are striking in their ability to capture a kind of out-of-time noble or aristocratic manner.

As Zadie Smith wrote in a 2018 essay for Lawson’s Aperture monograph: “Deana Lawson’s work is prelapsarian—it comes before the Fall. Her people seem to occupy a higher plane, a kingdom of restored glory, in which diaspora gods can be found wherever you look: Brownsville, Kingston, Port-au-Prince, Addis Ababa.” To Nguyen, this kind of framework was a revelation. She asked herself: What am I even doing if I can’t put my people on a pedestal?

Nguyen’s photographs in As You Grow Older are a serious attempt at exactly that. She asked friends, colleagues, and acquaintances to pose for her, sometimes staging them in intimate settings such as their bedrooms, other times in unfamiliar spaces. In one memorable photograph, three women stand defiantly in the center of the frame, each striking an identical pose, their hands on their hips, like a line of chorus girls. But the image is unsettling in its power, even though its setting—a dimly lit hallway of an apartment walk-up—is ordinary, almost bland. Nguyen was, in fact, referencing a pose from a historical image she had come across, of three Vietnamese women on the verge of being executed by European settlers, their necks shackled together by chains.

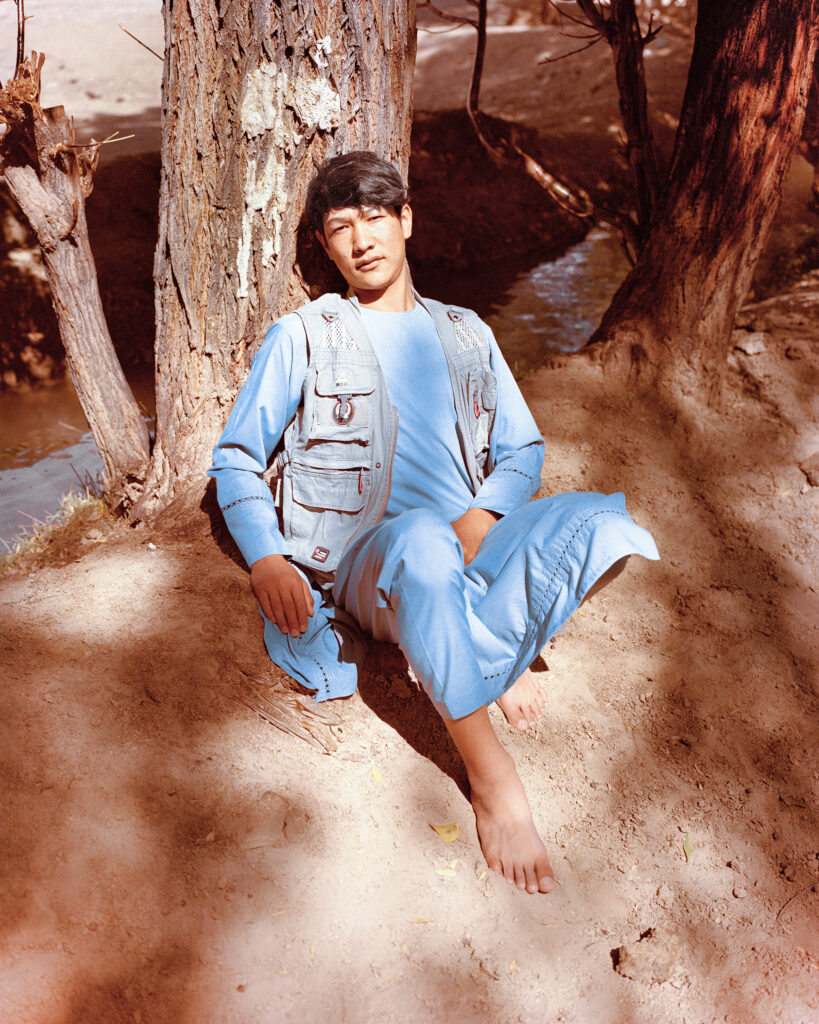

“Even though that image was taken by a white person, a settler, the women looked as though they owned the space,” Nguyen observed. In her pictures, masculinity, too, is its own kind of pure beauty: two young men lean against each other at night on the banks of the Hong River; another young man poses calmly on a bed, shirtless. Nguyen has a knack for seeking out the idiosyncrasies of those around her, to find intimacy with her gaze. Under her lens, the flattening stereotypes of Vietnamese culture are never present, even if she is perfectly aware of them.

Lately, Nguyen has been productive, completing the first portion of a series of photographs called Under the Sun, taken by the Siem Reap River in Cambodia earlier this year, and is at work on an upcoming show this August with Aperture. Her relationship to photography is still complex. “I feel like I’m in a marriage,” she says of her art. “Some days, I can feel intense passion for it that feels like I could survive off photographs and images alone, and some others, I just want to stop altogether and never touch a camera again.” But she is spending more time deepening her craft. She allows herself to fall in love with people and places. She is open to where photography will take her next.

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Vietnamese Pieta, By the River), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Vietnamese Pieta, By the River), Vietnam, 2022All photographs courtesy the artist

Vân-Nhi Nguyen is the winner of the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize. A solo exhibition of her work will be on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York in August 2023.

This piece appears in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian In America,” under the column “Spotlight.”