Interviews

Zen and the Art of Photography

Mark Steinmetz and Irina Rozovsky discuss the mysteries of the darkroom and the gifts of close looking.

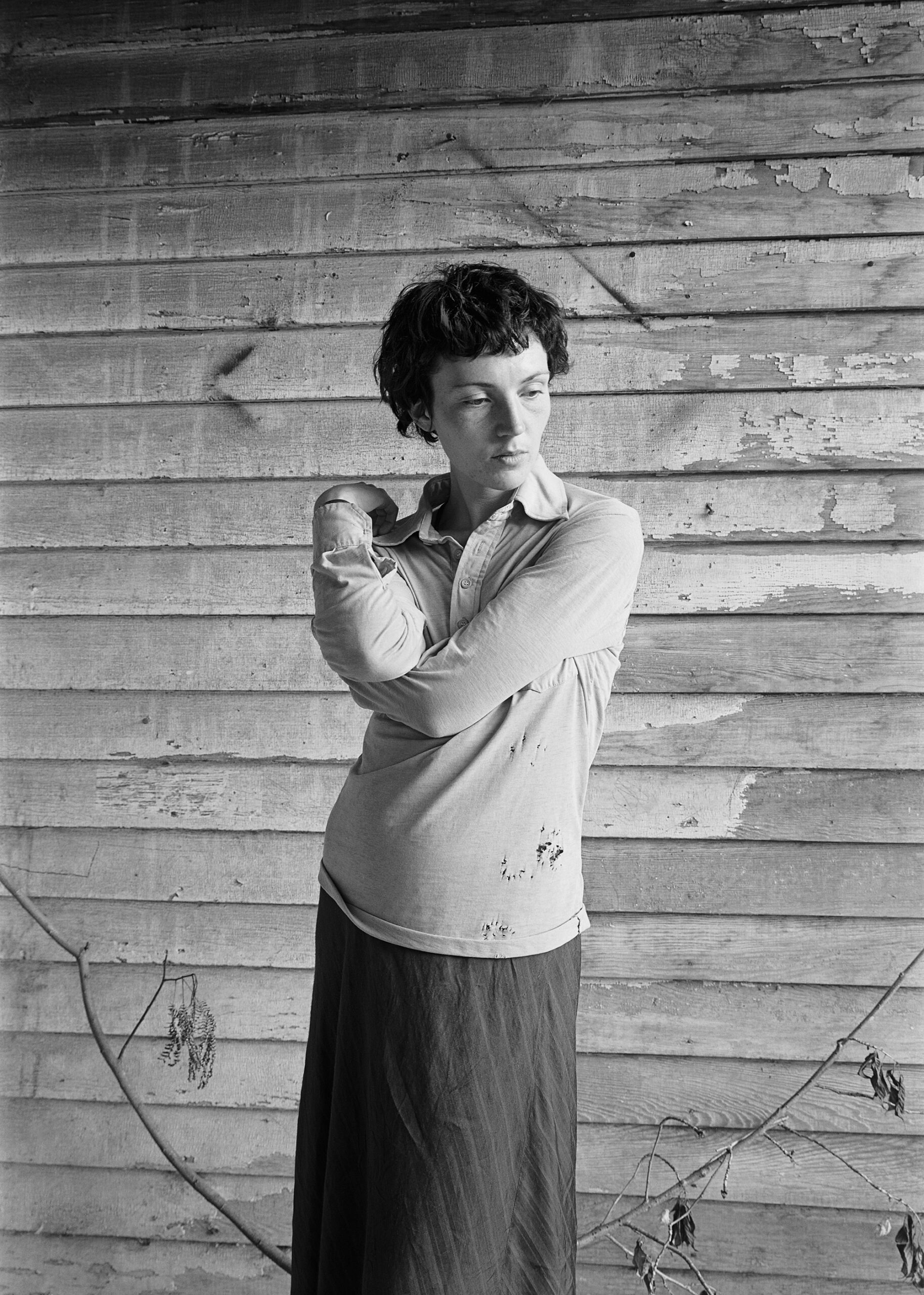

“You never find treasure on a mowed lawn,” Mark Steinmetz once remarked, describing his attraction to dog-eared, slightly peripheral American places, often in the South. Before his lens, everyday moments are frozen with a dollop of stylized romance and melancholy worthy of 1960s French cinema. Irina Rozovsky, too, seeks out moments of quiet contemplation—parkgoers in Brooklyn basking in magic-hour light, still lifes from the Balkans. She has also experimented with presentation, displaying her photographs in intimately scaled decorative frames purchased from eBay. Steinmetz and Rozovsky are partners in life—with a young daughter, Amelia—and they are partners running The Humid, a photography project in Athens, Georgia, offering workshops, lectures, and traditional analog training. Here, they talk with Michael Famighetti, Aperture’s editor in chief, about alternative approaches to teaching the craft of photography, the physical labor of making pictures, and the rewards of close attention, both out in the world and inside the darkroom.

Michael Famighetti: Why did you decide to create The Humid?

Mark Steinmetz: Well, when we got married, Irina had a job in Boston at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. But I was struggling a bit in Boston, with winter in particular, and I just had left this nice empire in warmer Athens, Georgia . . .

Famighetti: An empire?

Steinmetz: A modest empire—a darkroom, a workspace, ample storage space for prints and negatives, a great community. Nothing I could duplicate in the big city.

Irina Rozovsky: My life was in Boston—college teaching job, friends, family, but in 2017 I thought, Okay, start over in Georgia and build something of our own. When we got down there, I didn’t know anyone, just Mark and our baby daughter. But for the first time I had space—mental and physical. We got a big studio where I could spread out my work, and create this photography outpost center we’d been envisioning. The first thing we did was try to name it—nothing lens-, light-, or camera-related like—I’m sorry—Aperture. We landed on The Humid. It’s weird and true to where we are. People hear “The Human.”

Famighetti: What values around making photographs are baked into the mission of The Humid? You invite many great photographers there to teach.

Steinmetz: Well, if Baldwin Lee is there conducting a workshop, he is just being Baldwin Lee, and he’s offering his point of view. We’ve had Barbara Bosworth. We’ve had Mike Smith, Matt Connors, Curran Hatleberg, Robert Lyons. We’ve had a lot of other visiting lecturers.

Rozovsky: And we conceived of The Humid at a time when straight photography had gone dark in the art world. Everything being shown or celebrated seemed to have a conceptual lean. We’re interested in every kind of image, but we’re proponents of realism and making work in and with the world. It felt important to defend that old idea that life is stranger than fiction. The Humid is our way to share a particular vision and ideology. It’s a casual but very serious outlet for like-minded photographers looking to better understand their own work. It’s become a network, both international and also very local. We teach abroad, host virtual artist talks and students from many different countries, and organize portfolio reviews across time zones. But we also want to be a local resource and organize shows and talks to the community in our physical space.

Steinmetz: And the students who come want to be with us, they seek us out. They travel to Athens. We’ve had many in their twenties, but mostly, they’re older, in their thirties and forties and fifties. It’s for people who might want to go to grad school or, rather, don’t want to go to grad school and yet want to get some graduate-school-level critiques. Sometimes, they’ve already been to graduate school and just want to come in for a tune-up.

Rozovsky: In undergrad especially, you have some talented nineteen- or twenty-year-olds, but everyone’s living out the same chapter of life, more or less. In these workshops, age and life experiences really vary. We’ve had people who are wildly successful professionals in surprising fields, but on the side, they’ve also been developing an incredible body of work alone. They just come out of nowhere with this secret love affair with photography and blow us away.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Famighetti: Do you each have a philosophy for teaching, or an approach to making pictures, that you try to impart?

Steinmetz: I look at students’ work, and I think I can tell when they’re really interested in what they’re doing, when they’re being authentic, and when they’re more or less imitating someone else or just have a kind of set idea about how a photograph should be. I think I help students connect to the moment when they’re really surprised, fully reacting to something. Students can trip themselves up by overthinking. We try to help them to get clearer.

Rozovsky: Yes, Mark asks tough questions that shake people up. In a good way. My hope is to find what’s very specific and unique to each student—their particular way of seeing and being in the world. And to help them shape words into a sentence—the way unrelated photographs gravitate to each other and create meaning, narrative, a nest. People come with pictures that they’ve separated into distinct projects, and they might be very strict about it, but I might start putting them all together, moving things around, and it’s like alchemy—pictures start to speak to each other and everyone gets excited. It’s powerful to witness someone’s moment of clarity or inspiration. People might come in thinking their work was one way but leave knowing it’s more.

Famighetti: There is a strong emphasis on darkroom technique, too, and the craft of printing.

Steinmetz: I’ve offered several darkroom workshops in my own darkroom. It’s intended for people who are serious about doing black-and-white photography, to help provide some shortcuts and demonstrate how I work. I show how I make an archival print, how I burn and dodge, how I evaluate a print, and the setup I’ve got.

Famighetti: You’ve spoken before about how labor-intensive this process can be.

Steinmetz: Anybody who says photography is just mechanical reproduction—that’s ridiculous. It’s all so athletic and physical. I love shotmaking, and to me, playing tennis serves up some of the same thrills.

Rozovsky: You love games in general.

Steinmetz: If you’re being sluggish, you’re not going to execute the picture well. Your body’s got to be able to swoop in and strike quickly. Sometimes, you don’t even know what’s happening.

Printing is arduous. You’ve got to be able to focus. You don’t want to be crazy when you’re printing, where everything one day turns out to be too contrasty or pale the next day. The baths, moving the print from here to there—there’s so much to it, especially if you want to maintain your darkroom’s cleanliness so there’s no fixer contamination, so that your prints are indeed archival. There’s a lot to think about all the time. It’s very strenuous. It’s especially true for black-and-white photography, and there’s a lot to consider with film development. What’s causing air bubbles on the film? In winter, for instance, there are more air bubbles because the water’s going through the water heater. I’ve thought about air bubbles and how to eradicate them to an embarrassing degree.

We conceived of The Humid at a time when straight photography had gone dark in the art world.

Rozovsky: Inkjet printing is definitely less physical—also less magical and romantic—but it’s still a labyrinthian process to make a print “right.” There are a million ways a photograph can look on paper—maybe too many options. And you need to make many prints to land on the iteration that feels right, because when it has to do with atmosphere, time of day, light, skin, color, et cetera, you really need to sense what the picture is meant to express, and any exaggeration of tone can kill its spirit.

Famighetti: Mark, do you exclusively work in analog?

Steinmetz: I use a tiny bit of digital for fashion work. But yeah, I don’t think I can get what I want on an inkjet print. Nick Nixon once said to me, “Digital is great. It’s 98 percent there,” which meant that it wasn’t good enough for him. There’s this tremendous pressure now because the price of silver-gelatin darkroom paper is so high, and the cost of film is so high, and the chemicals have gone up in price. There’s the water. Once you start, you’ve got your water running. You don’t want to waste it. You’ve got your chemicals that are to some extent oxidizing. It’s like Mission Impossible. The timer is going off. You just can’t cut out for two hours. You’ve got to have everything planned. You’ve eaten, you’re ready, you go in, and you just keep at it.

Famighetti: You must be completely present and dialed in.

Steinmetz: You’ve got to be completely present. You don’t want to wash your prints for too long, especially because there’s optical brightener in there. We filter our water for the whole house, so the chlorine and lead are removed, and other heavy metals and sediment. But still, there might be stuff in the water, so you don’t want to wash it for too long. With every sheet of paper, you’re kind of trembling. I will make blood-curdling screams if I bring a sheet of paper over to the enlarger and I haven’t stopped down the lens, if it’s at f/4 instead of f/8, and I’ve wasted a sheet of paper—it’s just like, AAARGH!

Famighetti: Are the students you attract coming to you to learn what is now a very specialized skill?

Steinmetz: Yes, but often I’m seeing very poor print quality. I don’t think they’re inside the process. Most photographers don’t work in silver prints anymore. A lot of the digital prints just kind of come out of the machine, received . . . I always say that with digital prints, it’s like every object has been oversharpened. Every object in the frame seems estranged from every other object. There’s not this kind of harmonizing, settling in that you find in older versions of darkroom photography. Not everybody feels this way.

Rozovsky: I feel so lucky that when I started shooting color, analog printing was still the thing. C-printing was totally revelatory, I’m sorry people don’t get to learn color that way any more. In grad school, the darkroom was on one end of a very long hallway and the processor was at the other end. Walking the exposed sheet in a light-proof box took forever; I was so impatient to see the results that I got roller skates to speed things up. Those C-prints, as faded as they are now, were fundamental to my understanding of color, and inform how I work. There’s something sort of twisted about shooting film only to digitize its output, but it’s where we are now. I know I need to work with and somehow against the technology, so it doesn’t take over creatively. It can do anything you want, really, but you need to be the boss.

Famighetti: You have a dedicated meditation practice, Mark, and the way you described printing and a rigorous concentration on air bubbles seems to reflect that. How has meditation influenced your practice? I’m thinking about that Eugen Herrigel book Zen in the Art of Archery (1948), which is important to many photographers.

Steinmetz: That’s a great book, one I recommend to students. There’s also that once-popular book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. It’s the same thing. People think they can spend tons of money on equipment and somehow avoid grief. But gosh, everything is physical and everything can break down. You can’t take it for granted.

I would say that meditation is very helpful in giving you the ability to pause. The pause can be when you’re taking photographs. I want to be the one responsible for the picture I’m taking. I don’t want to just go click, click, click, click, click, and then select the best one. I want to really be present and to click at the right time. There’s a lot to meditation that I think helps with your intuition, and I think anticipation is a big deal in photography. Why are you all of a sudden moving toward this direction? What is this about? I’m not really talking about the “decisive moment,” because that’s sort of an obvious crescendo. All moments are kind of decisive. You’re moving toward something that, as Robert Adams says, there’s an “inexplicable rightness” to.

Rozovsky: Do you think meditation helps you move?

Steinmetz: I think it helps you to inhabit your body and to be present in the moment and to be able to know: I was really here when I took the picture. The photograph is not an accident. I mean, you can say that it’s lucky; it’s like a chance encounter. But on another level, maybe luck doesn’t have much to do with it. For you, too, Irina, the taking of the picture is very physical, especially with your iPhone photographs. You’re moving the camera around.

Rozovsky: True, I love iPhone acrobatics. I call it the microwave dinner of photography: inherently crappy but so fast and easy, and because I’m hungry for pictures, it hits the spot. I do think that with it I am sort of less present than what Mark is referring to in that I shoot a lot of the same scene, maybe too much, and hope something sticks—like throwing a bucket of darts at the board and waiting for one to touch close to the target. When I have twelve shots on film, each dart is on a precious, intentional mission. So, while I’m not at war with the air bubble, the struggle is the ever-shifting target.

Famighetti: Irina, how do you view that idea of anticipation Mark mentioned earlier?

Rozovsky: For me, anticipation wraps around surprise. They work in tandem and need each other. I’ve been photographing at the supermarket. It’s rich material for me, both anonymous and intimate seeing what people take home to feed their families. I anticipate a photograph at this entrance, by this display, the light hits from the window, and the cans of whatever are glowing. But it’s not until someone I didn’t anticipate passes through and blows away my expectation of a real photograph. Picture making is like a strange maze, and there’s a frustration and euphoria to it. Frustration in not quite knowing if and when a photograph is going to announce itself and then the pure joy when it shouts, “Over here!”

Famighetti: That’s always the uncomfortable thing to sit with, the not knowing. Is there an exercise you like to have students do, involving constraint or something?

Rozovsky: We used to always start off with influences. One time, everyone was like, “Oh, Ansel Adams is what got me into photography.” Then I just got so tired of looking at Ansel Adams. The last workshop we did, I wanted a change and asked students, “What photography do you hate?” Or, “One image that you love and one that you hate?” And everyone brought in Ansel Adams.

Mark Steinmetz, Bent Tree, Athens, Georgia, 1995

All photographs courtesy the artists

Famighetti: The love-hate relationship with Ansel! Do you want to distance the students from influences?

Steinmetz: I think they’re key: “Who got you into photography in the first place?” “What made you want to be a photographer?” Ansel Adams is a big reference for people maybe starting in the 1950s and 1960s, and Cartier-Bresson certainly. We have a lot of students coming to us who cite Eggleston. I think Sally Mann, the tonality of her prints, was important to many.

Rozovsky: It helps to see where someone is coming from, not just in the photographs they make, but what got them going. It’s like a mother tongue or a sort of DNA.

Famighetti: How would you describe The Humid as related to location? The geography is so specific, and as you noted at the start of this conversation, connects back to the name, a strong sense of place.

Steinmetz: There are railroad tracks running right alongside us at The Humid. The street we’re on in Athens is a long, mysterious street. There’s overgrown vegetation everywhere, old mill-worker housing. The street is close to downtown and leads to it. One thing we’ve been thinking was organizing a festival one day in Athens, probably when the students from the University of Georgia are off, because it’s very walkable. There are all these great bars and restaurants and all these places that could be wonderful venues for artists’ presentations. There’s a mill building right across from The Humid, across the street on Pulaski, that’s eye-opening, just a huge, crazy vaulting space when you’re inside there. It would be a real treat. America is lacking a walkable photography festival in the vein of Arles. One in Athens would, of course, be much smaller. It would be a nice place where people could meet and talk about photography.

Rozovsky: It’s a bit of a destination. We’re here to ask if you’d like to be chairman of the board.

Famighetti: Count me in. In moments of technological change, as with the digital ascendence over recent decades, we see photographers turning toward more traditional, or hand-oriented, techniques—photograms and other process-based work, for example. We’re now at another inflection point with the rise of AI and its ability to generate images. Do you see this influencing the students who seek you out, in part, because of your attention to a black-and-white darkroom process?

Steinmetz: Well, hopefully as people become familiar with AI, they’ll be able to recognize it wherever it appears, feel it out, and then come to know what is unique about our human experience and human creativity. I think there’s a lot of photography that might as well be AI. It’s trying to satisfy formulas and expectations. What’s something that’s unique and authentic and deeply human? If AI starts presenting to us what the human experience is, that could lead to us devaluing our human experience.

Rozovsky: But do we know entirely what the human experience is? I mean, maybe AI is part of the scope of human experience. Not that I like it.

Steinmetz: I made all this work on Little League baseball. There’s one picture that I usually show, which I call my Guernica. It’s with a short telephoto, and you’ve got five kids, their hands are clenching, their eyes are shut. They’re trying to catch a ball. The ball’s halfway in a mitt. But there’s one kid who’s missing a tooth, and there’s Kleenex sticking out of a pocket. Maybe AI can figure that out. But AI would never, ever get the string that’s coming down from this coat, because it’s just too wacky, you know? And it would never know . . .

Rozovsky: Be careful. It’s listening.

Steinmetz: I know. But it would never know what it’s like. Because on your baseball mitt, which is made of leather, there’s always a strap down, and it would never know what it’s like to chew on that leather strap. It will never have that experience, which most every kid playing baseball has. It will never have any human experience. It’s just probabilities. And it’s great for that. But we have to have the self-esteem that, yes, we are indeed the boss. We’re having these experiences, and these experiences really matter. This is a great ride, this life.

Rozovsky: I agree, there’s nothing like it. Here’s to anticipating what’s next.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”