Essays

The Musicians Who Energized a Revolution in Nepal

Prasiit Sthapit’s photographs show how musicians—as both instigators and healers—influenced an insurrection that shook the country.

When the People’s War began in Nepal, in 1996, eight-year-old Prasiit Sthapit noticed that his great-grandfather’s portrait had suddenly disappeared from the living-room wall. Later, as an adult, he realized that the picture of the mustachioed man he had assumed to be his great-grandfather was, in fact, a framed poster of Joseph Stalin. Sthapit’s grandfather, an ardent Communist, looked up to Stalin. In the decade-long, violent armed conflict between the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN-Maoist) and the state, anyone left-leaning was seen as a Maoist sympathizer, and many were arrested or, worse, disappeared. During Sthapit’s teen years, his family’s political leanings, as well as his own youthful romanticization of what a revolution symbolizes, made him curious about the bloody rebellion that shook Nepal.

His interest in this history deepened in 2006 when, at age eighteen, he took a spontaneous trip with friends, a month after the war had ended, through the western Nepali districts of Rukum and Rolpa—the heartland of the revolution. These areas had been a war zone just weeks before. “We saw bullet holes on bridges and houses. I met many Maoists; some were curious and kind, others not so much. I realized how sheltered we were in Kathmandu, and how the war was not over in the minds and lives of many people,” Sthapit told me over coffee one morning last fall in Kathmandu. Many in the capital initially experienced the war as something that would never reach them—just some hooligans making noise with pressure-cooker bombs that would surely die down in no time.

But the war lasted ten years, and in that time, many brothers, sisters, friends, and relatives, fighting on opposing sides—with the Maoist-led People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or the Nepal Police—brutally killed one another. When the war ended, at least thirteen thousand Nepali men, women, and children had been killed, thirteen hundred disappeared, and thousands were left displaced and disabled. Although the war started in February 1996, the seeds of the revolt had been sown back in the 1960s. At the time, Nepal was brought under Panchayat rule, wherein the country’s leader, King Mahendra, instated an autocratic regime that saw the dissolution of parliamentary democracy, a ban on political parties, the imprisonment and exile of elected leaders, and the curtailment of freedom of expression and many civil rights. The Panchayat era was notorious also for instituting the erasure of the country’s diverse peoples, cultures, and languages under the slogan “one king, one nation, one language, one costume.” It was under this system that many Maoist leaders, then in their twenties, became radicalized.

Inspired by Peru’s far-left group Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), the Maoists waged guerrilla warfare, attacking police stations, acquiring weapons, using different aliases while living and working underground among the people, and recruiting new members through song, speeches, and stories. They gained momentum and support in the rural areas of western and midwestern Nepal. As the war progressed, news of casualties increased. Reports of bomb blasts became frequent. In 2001, the government declared a state of emergency. Even urban areas such as Kathmandu saw army patrols and barbed-wire checkpoints. Freedom of expression, movement, and assembly were curtailed; state crackdowns and raids in search of Maoists increased, as did countrywide shutdowns and curfews. The government declared the Maoists “terrorists,” violent revolutionaries whose image—in camouflage, a red bandana with a star tied across the forehead, guns in hand—became feared.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

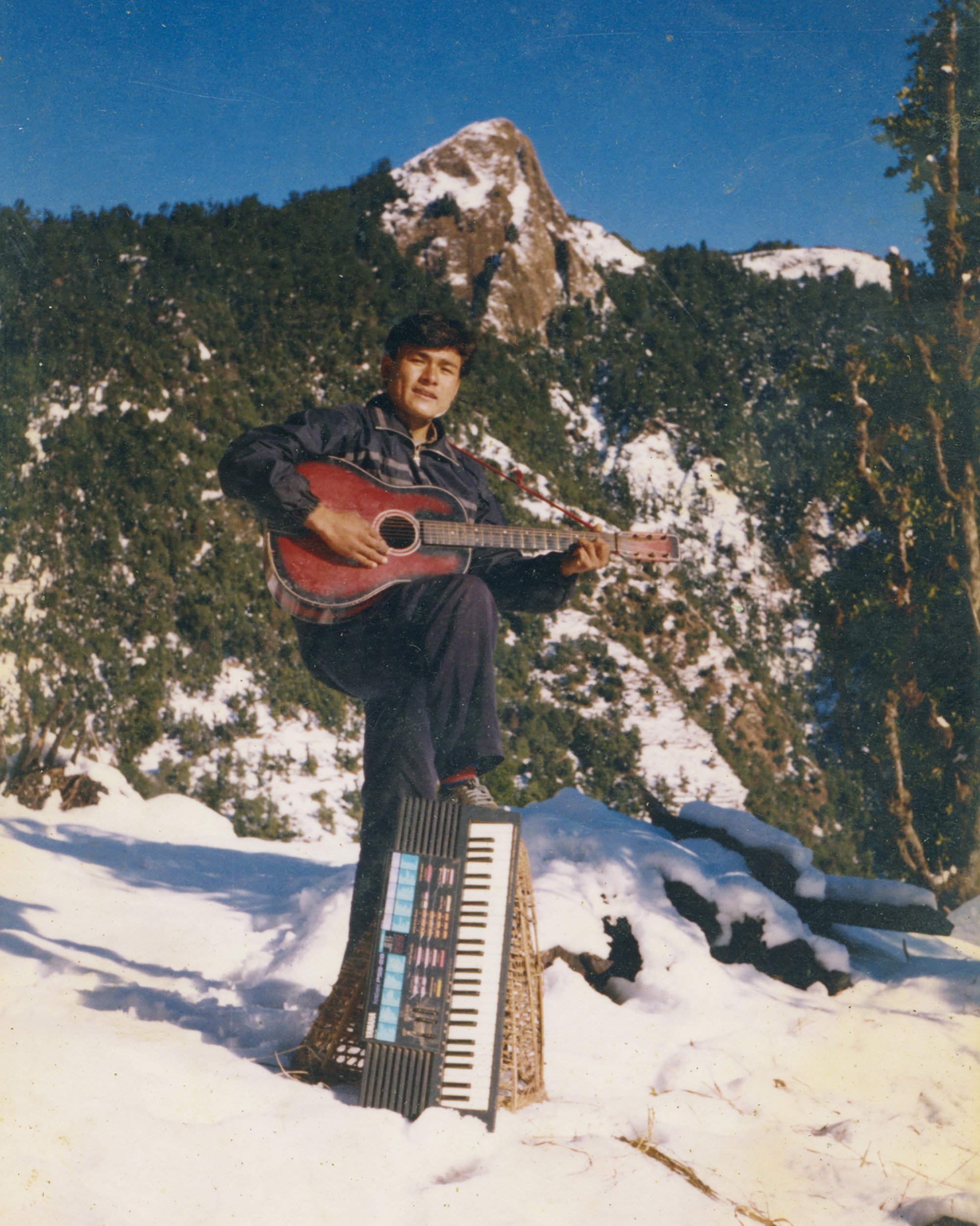

It is this one-dimensional view that Sthapit complicates in his project Moonsongs for Earth (2022–ongoing), a studied look at the musicians who energized the Maoist movement through song. “There was the PLA, who carried guns and bombs, and then there were musicians, who carried guitars and harmoniums,” Sthapit said as he scrolled through images from the series, which includes a mix of his own contemporary portraits, archival imagery, videos, interviews, and songs. Many of the archival photographs feature musicians posing in nature with their instruments, showing the world what they love and how they want to be seen. Group photographs depict them practicing and performing. “We had seen plenty of war images in the media, but I wanted to see the war through the eyes of the musicians,” Sthapit explained. “These intimate musical sessions too were a part of the war. These musicians held and spread the dream of the revolution through their songs.”

In 2019, Sthapit traveled to what is marketed as the Guerrilla Trail, a path the PLA used during the war that cuts across the spine of the country and branches out like a tree. He initially had begun working on a multimedia project to uncover stories of the war along the trail, until he met the former Maoist Jhankar Budha Magar, who sang for Sthapit a popular war song: “You must fight and win this final battle. Torn hearts and drenched bodies are waiting for a new day.” The song is part of an opera, Returning from the Battlefield, by the late Khusiram Pakhrin, a musician and cultural leader of the revolution. The opera was commissioned for the 2005 central committee meeting of the Maoist party in the village of Chunbang. This meeting would prove historic, as it opened a path for two feuding Maoist leaders—Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Baburam Bhattarai—to reconcile their differences. A video from the gathering captures the two visibly sobbing as they watch the opera, which presents the story of a soldier’s death, his willingness to sacrifice himself for the larger cause, and his wife’s plea to continue fighting to fulfill the dream of the revolution. The Chunbang meeting would be followed by the formation of an antimonarchy alliance with mainstream political parties and a 2006 peace accord marking the end of the war. In 2006, the second People’s Movement began, and by 2008, the country’s 240-year-old monarchy was brought to an end. The new, secular Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal was born, with the Maoist party elected to office. Dahal became the republic’s first prime minister. Since then, the Maoists have come into power four times, and Dahal is currently the country’s prime minister.

The music was medicine, a balm, and also a reminder for fighters who were alive to continue the mission of building a just world.

Would the outcome in Chunbang have been different had there been no musicians, no opera, no tears? “Our duty was to sing encouraging farewell songs to our friends going into battle,” the musician Laxmi Gurung told Sthapit during an interview from her home in Kathmandu. In 1999, the twenty-two-year-old Gurung joined the Maoist party after the state killed her father. “Everyone used to think of me as the daughter of a Maoist who would amount to nothing. I didn’t join the party only for revenge, but I wanted to show that I could change the world and make it beautiful,” she said. Later, Gurung lost her daughter during the conflict. And it has been more than twenty-four years since her husband went missing. Today, Gurung, now forty-six, doesn’t want violence: “If there has to be another war again, I hope it will be a war led by love, and a war where we fight with our ideas to change society, not guns and bombs.” During their conversation, she broke into a popular war song: “In the battlefield, my friend, in the battlefield. The lives of the brave will flower in the battlefield.” Midway through, she stopped singing and let out a sharp laugh. “How can life flower if you’re dead? But that song would get everyone riled up. Everyone would be ready to kill, ready to give their lives.”

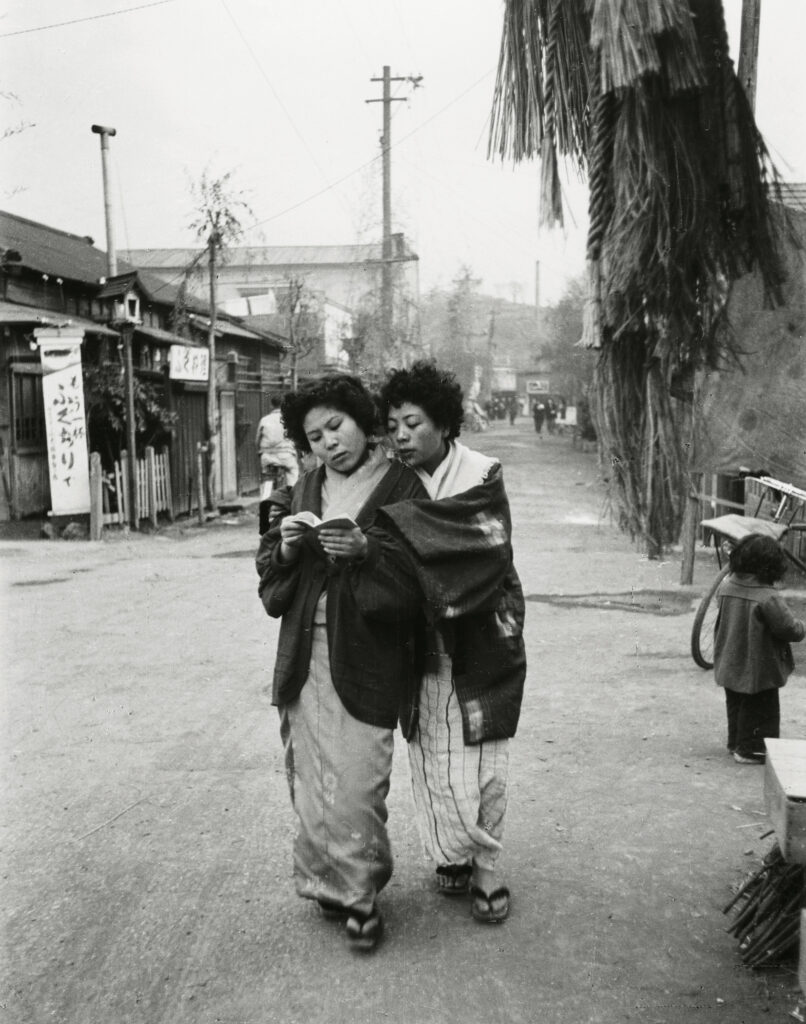

Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

The musician and educator Pradeep Dewan, who calls himself “the people’s artist,” described music as the salt of the revolution. Like many Maoist musicians, Dewan was influenced by the progressive songs of the 1960s and ’70s, most composed by left-leaning Nepali writers and musicians whose lyrics brought people to the streets to protest against Panchayat rule. But even with a movement toward democracy in the early 1990s, Dewan saw little change. “Everyone had a feudal mindset that they couldn’t seem to shake,” he explained to Sthapit. In 1997, Dewan joined the Maoists. Like many on the movement’s cultural front, he traveled around the nation, training other musicians and convincing people to “walk the path of revolution.” They wrote and performed hundreds of songs to excite, educate, and capture the hearts and minds of various oppressed groups: the poor, women, Dalits, and farmers.

The musicians were also healers. After battles, they sang songs to not only memorialize the dead but console their families and friends, as well as the many who were wounded. The music was medicine, a balm, and also a reminder for fighters who were alive to continue the mission of building a just world. Today, some musicians express frustration that the goals of the revolution—equality across caste and class lines, health care, good schools, security—were never fully realized. The popular musician and writer Mohit Shrestha expressed anger and betrayal. “I’ve thrown away all my diaries with lyrics and unrecorded songs. They did not feel important. I didn’t know that someone like you would come looking for them one day,” he told Sthapit. “These songs painted a dream of a revolution, but they didn’t bring the change we wanted.”

Moonsongs for Earth not only shows us a different aspect of the war but also illustrates what hope can look and sound like. “I am not trying to glorify war,” Sthapit told me. “The war was not only gruesome, it was a disastrous failure in many ways, but I think the motivation behind any revolution has to be considered. These artists, these humans, really believed that their singing and their music would bring change not only to Nepal but to the entire world.” Today, many of them are invited to perform original and cover songs on radio or television, or they find audiences on social media and YouTube. While some are still affiliated with the Maoist party, others have moved away from politics altogether.

As an image maker and a storyteller, Sthapit is an expert at revealing and concealing, nudging viewers to understand that things are not always as they appear. When I asked what surprised him most while making Moonsongs for Earth, he said that it was Laxmi Gurung’s vulnerability. He hadn’t expected a “steely Maoist fighter” to be this soft. “She thinks there is no one in the world who cries as much as she does,” he explained. “During the war, she would go into the forest, or lock herself in her room, and just cry. Even today, she cries when she composes music. Everything touches her.”

Courtesy Laxmi Gurung Collection

Courtesy Mahesh Arohee Collection

Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

Photographs by Prasiit Sthapit © the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation.