Photobooks

5 New and Notable Photobooks

From Jamel Shabazz’s singular record of Black joy to Roe Ethridge’s monument to art and commerce, here are reviews of five recent books.

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Jamel Shabazz

If you want to understand the look of life on the streets of New York City in the 1980s, turn to Jamel Shabazz and his singular record of Black joy and sartorial flair. After a stint in the US Army, stationed in Germany, Shabazz returned to his home of New York. He worked on Wards Island and as a corrections officer on Rikers Island, the city’s notorious jail, at the height of the crack epidemic and the “war on drugs,” which devastated communities of color. On the weekends, he traversed the city, making portraits of individuals and collective portraits of friends and families in collaboratively choreographed poses. In an era of take-and-run street photography, Shabazz worked slowly. He spoke with people. “When I look at you, I see greatness,” he’d say when approaching a potential subject. “If you don’t mind, I’d like to take a photograph of you and your crew.” The sidewalks and subway platforms of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx were his studio.

The long-anticipated book Jamel Shabazz: Albums (Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, 2022; 320 pages, $50) is not simply a record of how he archived his prints. Rather, it is a journey into his process. When he photographed, he carried an album of photographs, to earn the trust of those he wanted to picture by showing them the style, generosity, and care he brought to making a portrait. This smartly designed book reproduces these albums—conduits of human connection—at scale, in facsimile form, in their original arrangements. Spread by spread, we see couples embracing on graffiti-covered subway cars, friends posing in Kangol hats and fresh Cazal eyewear, loving fathers and mothers, children pausing from play to strike a pose. The cumulative effect is something between a yearbook, a lookbook, and a family album—it is a reminder that no one transmits the vitality of Black life and community in New York quite like Jamel Shabazz. —Michael Famighetti

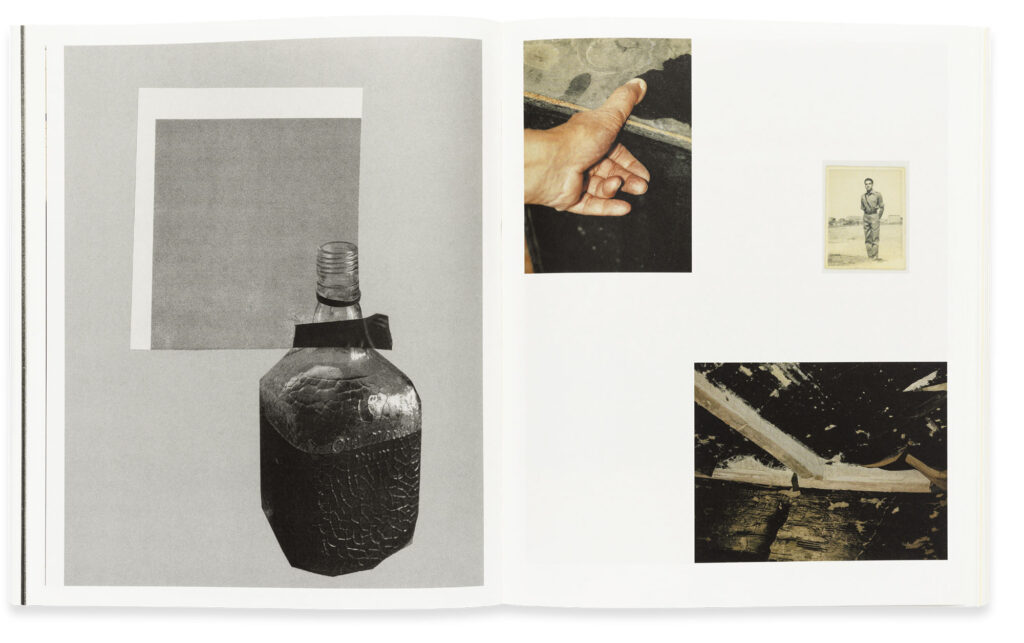

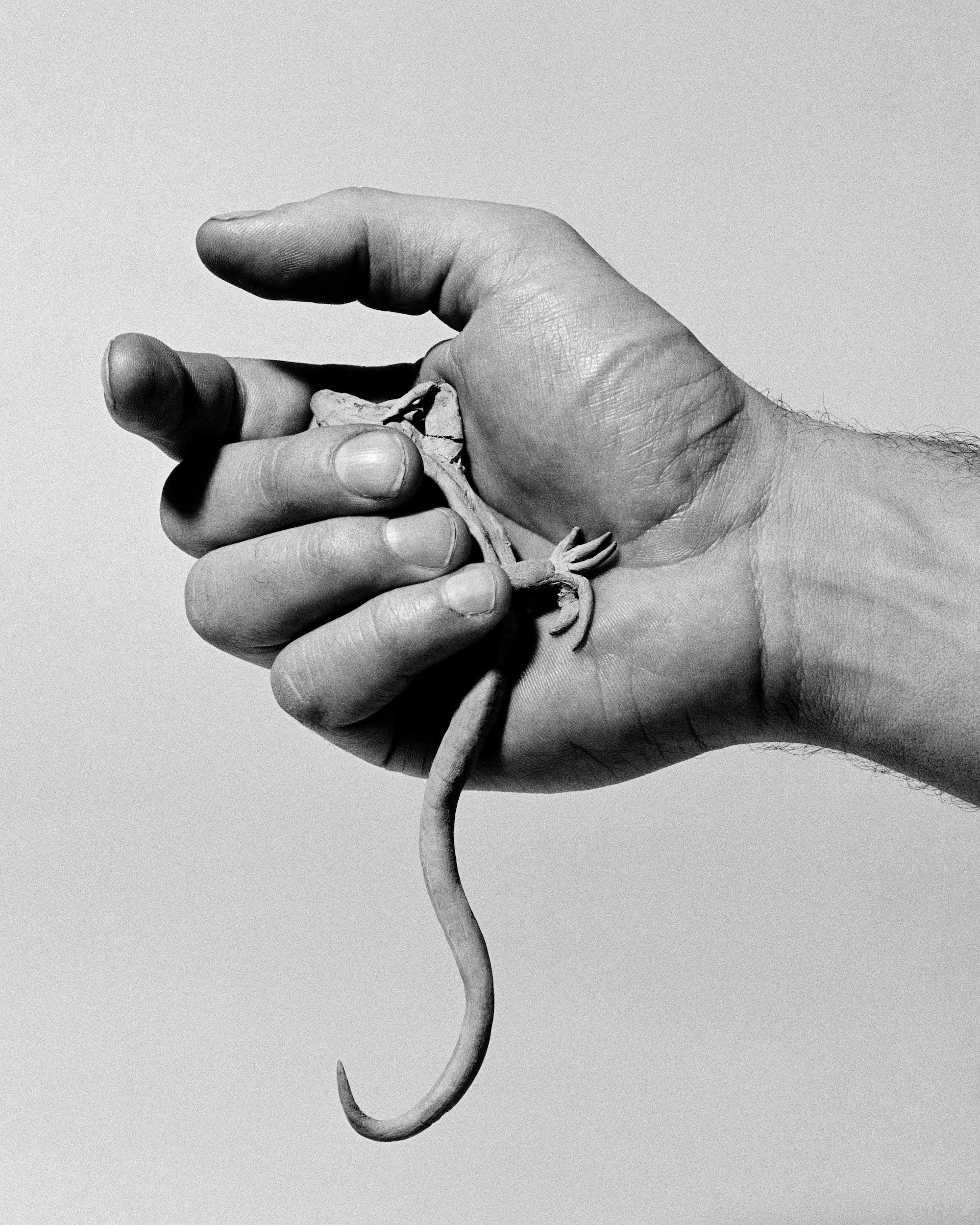

Bharat Sikka

Bharat Sikka’s long-term project about his father in The Sapper (Fw:Books, 2022; 192 pages, €40) is composed of fragments: a still life of his father’s tools glinting in the sun; a portrait of his desk left unattended. Other images depict the impression of the elastic of his socks on his calves and shins, the constellation of age spots on his back. These oblique but telling observations leaven a series of studies of his father’s face, of his figure in the landscape or caught up close in the burst of an off-camera flash. In The Sapper, Sikka’s approach to portraiture resonates with The Great Unreal (Patrick Frey, 2015), the Swiss photographers Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs’s American road-trip book.

Sikka was born in New Delhi and studied photography at Parsons School of Design in New York. He has frequently focused on the subject of masculinity, and his intervention with the artifacts of his father’s career as a member of the Indian Army Corps of Engineers pays tribute to a man’s life outside of traditional familial roles—in the book’s evocative presentation of sharply observed elements there is a puzzle to be worked out. His construction and deconstruction of photographs as a means of teasing answers out of these otherwise mute details is effectively underwritten by the book’s deft pairing and sequencing of images—patterns emerge and subside, only to return again. We remember, or think we do, but each moment of recall has been slightly altered from the last.

One segment in particular—an eight-page suite of full-bleed, black-and-white images reproduced to emulate cheap, Xerox-style copies—creates an enigmatic rupture in the otherwise gentle flow of images, confirming that something has been knocked asunder. An easy summation of Sikka’s subject of consideration lies tantalizingly just beyond reach. Instead, The Sapper offers an affecting negotiation of meaning and understanding of a father by his son, and a bittersweet confirmation of the fragility of memory. —Lesley A. Martin

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

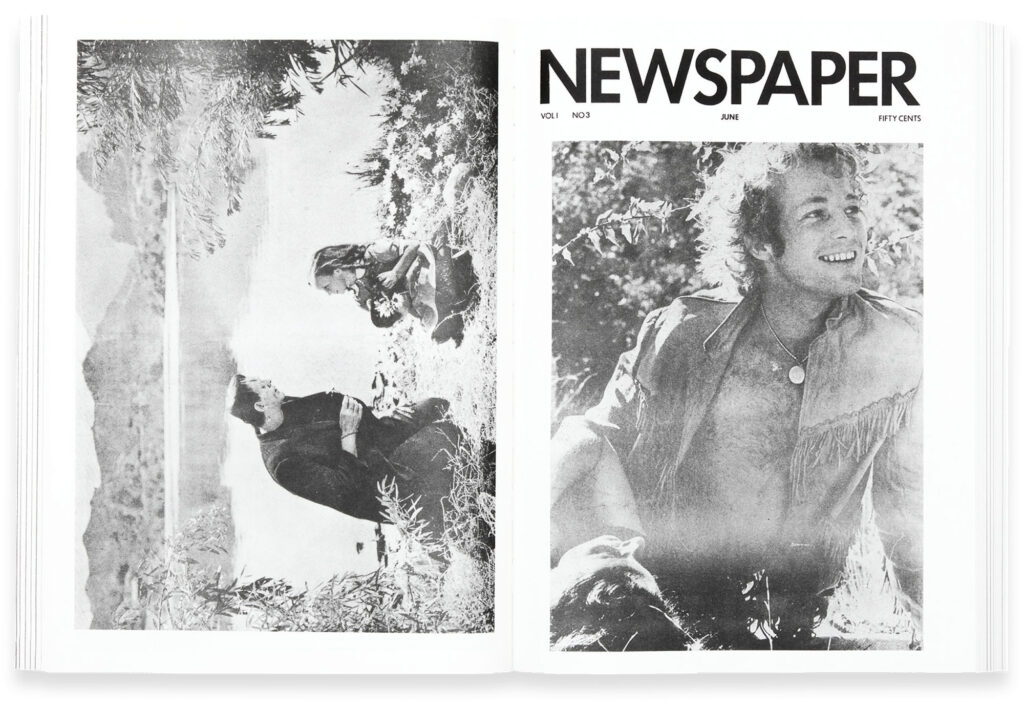

Newspaper

In 1968, Peter Hujar, Steve Lawrence, and Andrew Ullrick began printing and distributing Newspaper, a short-form, image-only, black-and-white newsprint publication. Over its brief three-year lifespan, Newspaper compiled a star-studded list of contributors—Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Andy Warhol, among many others—and provided a platform for artists to exhibit different kinds of work from what was shown at galleries at the time. Unfortunately, scholarship about and recognition of Newspaper has been limited; the ephemeral nature of newsprint (which resists archiving) and the original publication’s limited distribution and print run meant that after its end in 1971 it quickly faded into obscurity.

More than fifty years later, the Brooklyn-based publisher Primary Information has compiled the complete fourteen-issue set of Newspaper for the first time. While, for practical considerations, Primary Information’s publication doesn’t replicate the original’s format and material, the issues are presented in their entirety, giving light to the boundary-pushing publication that Hujar, Lawrence, and Ullrick smartly edited. The content of Newspaper (Primary Information, 2023; 416 pages, $40), edited by Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez, is kaleidoscopic. The book forces the reader to consider connections between and create meaning across multiple visual registers. Photographs, drawings, collages, imagery from high and low culture—all chaotically coexist within the pages. The effect is befuddling, cerebral, and provocative. Reproduced in Primary Information’s volume, the content of Newspaper can at times feel dense and indecipherable.

However, once primed to imagine the work within its earlier form and context, one can sense the underlying dynamism between the riotous arrangement of imagery, the casual and disposable form of the original tabloid, and the larger ecosystem of artist publications and queer periodicals of the late 1960s and early ’70s. In his preface to a detailed timeline of Newspaper’s history included in the back of the book, Yáñez clearly states his intentions: “to make the periodical accessible as a document. My hope is that by doing so, further information and scholarship about Steve Lawrence and Newspaper will arise.” —Noa Lin

Giulia Parlato

Giulia Parlato is drawn to false accounts and fictional retellings, to the tension between museums and cultural objects—particularly how each endows the other with historical meaning. The Italian photographer conceived of her debut photobook, Diachronicles (Witty Books, 2023; 120 pages, €35), while researching forgeries and counterfeits at the Warburg Institute in London, and she argues that this meaning is first and foremost a construct, unstable and often the result of numerous interventions. Photographs play a split role in this equation, sometimes as displayed object and other times as document. For Parlato, they also offer a clever form of investigation and play as she appropriates the visual language of archaeological excavations, forensics, dioramas, and museum archives and displays to stage her own constructions, which are somewhere between evidence and fiction. Parlato’s photographs—which she made between her London studio, Sicily, and several European museums—appear stark and direct, almost instructional. A gap in the painted ceiling of an eighteenth-century palace in Palermo reveals innards of wood, stone, and rubber piping. Gloved hands confer archaeological meaning to an object concealed in tarp, seemingly exhumed from a dig. “Indeed, it is almost as if the more straightforward the imagery seems, the less straightforward it really is,” writes David Campany in his introduction. A curious reader might equally wonder whether the lack of context, and the book’s rather austere layout, limits its overall effect. One must invariably work backward and reconstruct the story; must look, and look again. By developing fictional histories from fragments and fakes, Diachronicles is both about what is said and what is withheld, positioning the photographer as both chronicler and unreliable narrator. —Varun Nayar

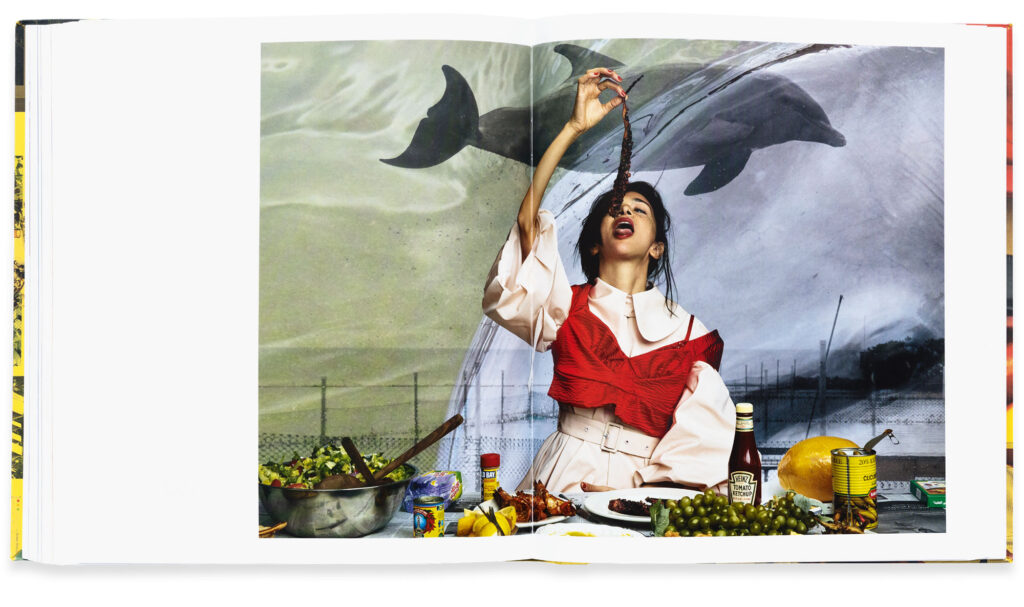

Roe Ethridge

A refrigerator, a black eye, a tennis player, a highway. Chloë Sevigny, Willem Dafoe, Weebleville, and then—wait, an ad? For Hermès? Oh, this is a Roe Ethridge book! Ethridge being the American photographer who has unlocked that little velvet rope between art and commerce to delirious and delightful effect, who has compiled four hundred “and something” images into a massive book, American Polychronic (MACK, 2022; 480 pages, $70), “some of which were for art exhibitions and some which were made for magazines and advertising,” as he notes in an addendum. “A healthy portion are both and a lesser portion neither.” So, anything goes, from a babe in a bikini to Telfar Clemens naked on a sofa to a screenshot of a conversation about a twenty-year-old Lexus. It all feels like a decadent European magazine (there’s even a French-fold dust jacket protecting the paperback covers), the kind you buy when you’re hungover and dreaming of a life in fashion. You certainly wouldn’t throw American Polychronic in the recycling bin, but is it a masterpiece for the bookshelf? Maybe! Jamieson Webster compares Ethridge’s photography to psychoanalysis—“symptom and repression are attacked through evoking an assemblage of fantasy, memory, and reality that shakes the frame”—in an essay printed in small type at the end of our photographer’s elliptical journey through his archive, from 1999 to 2022. (At first glance, the text appears quite literally like an afterthought.) Still, you didn’t come to American Polychronic, a production of staggering charm and shrewd editing, a monument to one of the most successful image makers of our era, to learn something new about fugue states or “hysterical flowers.” You came for the Chanel tennis balls, the beach umbrellas, the winsome smiles, the paper towels. You came for Anna, Karl, Hans Ulrich, Thanksgiving, laughter, tears, birds, sunsets, and “pure beauty” (as one chic cannabis brand would have it), beauty so pure and sweet you might need to take an aspirin and turn on Cat Power’s Moon Pix. —Brendan Embser

These reviews originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America,” in The PhotoBook Review.