Essays

A Mother’s Relentless Quest to Find her Missing Son

After her son disappeared from Hong Kong into China, Yu Lai Wai-ling embarked on a lifelong search to bring him home. The photographer Billy H.C. Kwok convinced Ms. Yu to tell her story, assembling images of grief and resolve.

The mother’s quest began on August 24, 2000. Her name was Yu Lai Wai-ling, a housewife who lived in a public-housing estate with her husband, a civil servant, and her son, an autistic teenager. Outside the walls of their small flat, a typhoon breached Hong Kong and calmed into a storm. The unsettling weather disturbed her son, so her husband suggested a diversion: lunch. After leaving a dim sum restaurant, the three huddled through the Yau Ma Tei underground station—and this was when the boy let go of her hand, sprinted into the crowd, and disappeared.

Ms. Yu was frantic. Her son, named Yu Man-hon, was a two-year-old in a fifteen-year-old’s lanky body. He couldn’t speak. How could he manage the packed underground station alone? She went to the police, whose website still displays a missing person photograph of her son: a thin boy, his eyes set slightly apart, his mouth drooping. Man-hon began a journey whose mysterious sequence we can reconstruct from a Hong Kong Immigration Department report released after his disappearance. After somehow traveling twelve miles north, he inexplicably appeared behind the Chinese border at 1:47 PM, despite lacking the permit needed to cross. At the Lo Wu border checkpoint in Shenzhen, Chinese immigration officials found the boy answered to Cantonese, not Mandarin, and returned him to Hong Kong.

Immigration officials there noted the boy’s disheveled state. He wore shoes from a Chinese brand. He didn’t respond when they asked him about Andy Lau, one of Hong Kong’s most famous celebrities. Panicking, the boy flailed his arms and spat at the officers, who handcuffed him to a chair. To them, he was clearly an “illegal” migrant. His poverty, the officers inferred, suggested a Chinese, rather than Hong Kong, origin, so they dragged him back into Shenzhen. That fateful last act separated Ms. Yu from her son.

In the coming days, Ms. Yu’s tearful, inconsolable cries circulated across the newspapers and TV news. A massive force of Hong Kong police officers flooded the city. Search teams scoured Shenzhen and Guangdong. Was Man-hon still alive? Had gangsters captured him? Did he become another unhoused migrant in China? The boy came to represent Hong Kong itself—a phantom languishing inside the foreign motherland that had absorbed the former British colony only three years prior.

Billy H.C. Kwok heard about Ms. Yu and her son when he was a secondary-school student in Hong Kong. Be careful at the border, his mother had told him. Now a boy not much older than him had vanished into China. Living today between Hong Kong and Taiwan, Kwok works as a photojournalist; his images for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal depict the contentious new Sinophone century: a Hong Kong protestor raises a flaming stick at riot police, steelworkers protest in Guangzhou, and a man fixes a flagpole outside a Taiwanese temple he’s taken over with Chinese flags. In the National Archives of Taiwan, Kwok uncovered letters written by those captured and later executed during the White Terror, the authoritarian wave of oppression that began in 1947. The letters were never delivered, until Kwok intervened to complete the correspondence. For his project Last Letters (2017–ongoing), he approached their authors’ families and photographed those who agreed to read them. The most fascinating part, Kwok told me, was observing the children of these victims kowtowing before statues of Chiang Kai-shek, the right-wing leader who presided over the persecution, only to gradually realize he had authored their own family tragedies. Kwok appreciated how these statues, whose removal he also documents, constituted both objects and manifestations of political ideology. Having made this archival interrogation into one alternative China, a project oriented less around visuality than the failure and persistence of ideological narratives within objects, Kwok wondered how he could investigate the story of Hong Kong.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

He recalled that lost boy he’d heard about growing up, whose story hinted at a surreptitious way to interrogate Hong Kong’s vexed status without triggering Chinese censorship. In June 2022, Kwok cold-called Ms. Yu, whose number he found in one of the many classified advertisements she’d placed looking for her son decades earlier. When he introduced himself as someone researching Man-hon, Ms. Yu told him to read the internet and the newspapers. I’ve read all the newspapers and the internet, he told her. You’re the only source. He plied Ms. Yu to meet him at a restaurant, where he encountered a woman he described as deeply saddened and driven by love and discipline. By their third meeting, she invited him to her apartment.

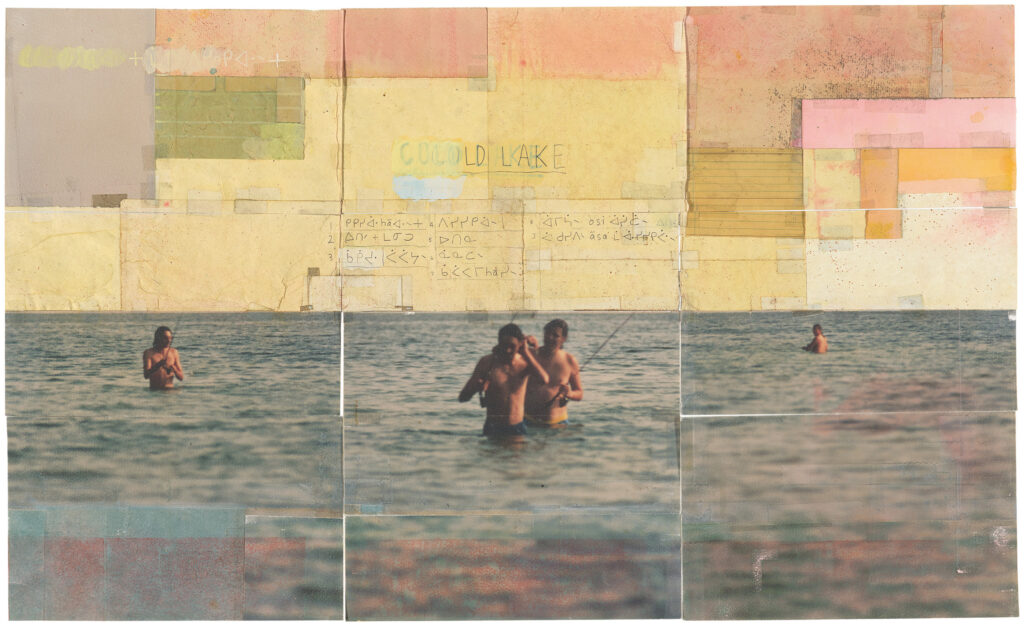

Kwok lived only two stations away, and he visited her every week for nine months, each time carrying his camera to acclimate her to the idea of perhaps one day being photographed. However, the photographs they focused on were not his, but hers. For one astonishing consequence of Ms. Yu’s son’s disappearance is how her search led her to deploy many of the techniques of art practice, such as object making, photography, and performance. Kwok’s ongoing project has been to curate and present her archive related to her son’s disappearance, and his initial instantiation, For So Many Years When I Close My Eyes (2022–23), combines elements of her images and records with his own maps and photographs created in locations related to her story.

Few forces in the universe are as powerful as a mother’s grief. Supported by donations from people who’d heard about her loss, Ms. Yu began creating notices asking if anyone had seen Man-hon. This media project included newspaper classified ads, text-based spots aired on TV and Hong Kong trains, and, remarkably, playing cards featuring Man-hon’s portrait. This collision of public memory and a simple deck of cards reminded Kwok of how the US military trained the soldiers invading Iraq to identify Saddam Hussein’s leadership circle by printing their faces on playing cards. Ms. Yu also posted missing person flyers in Shenzhen and elsewhere in southern China. A few of the flyers resemble zines or print art. Monochromatic enigmas, they show her son’s missing person photograph, an embellished image of him with long hair, and only the Chinese words missing person.

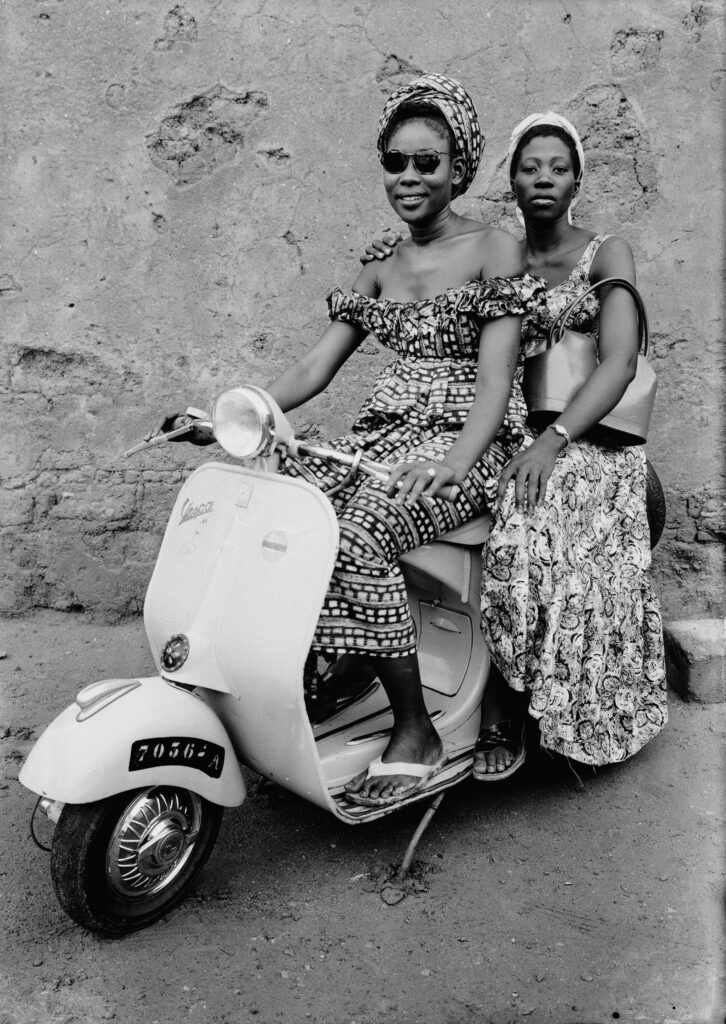

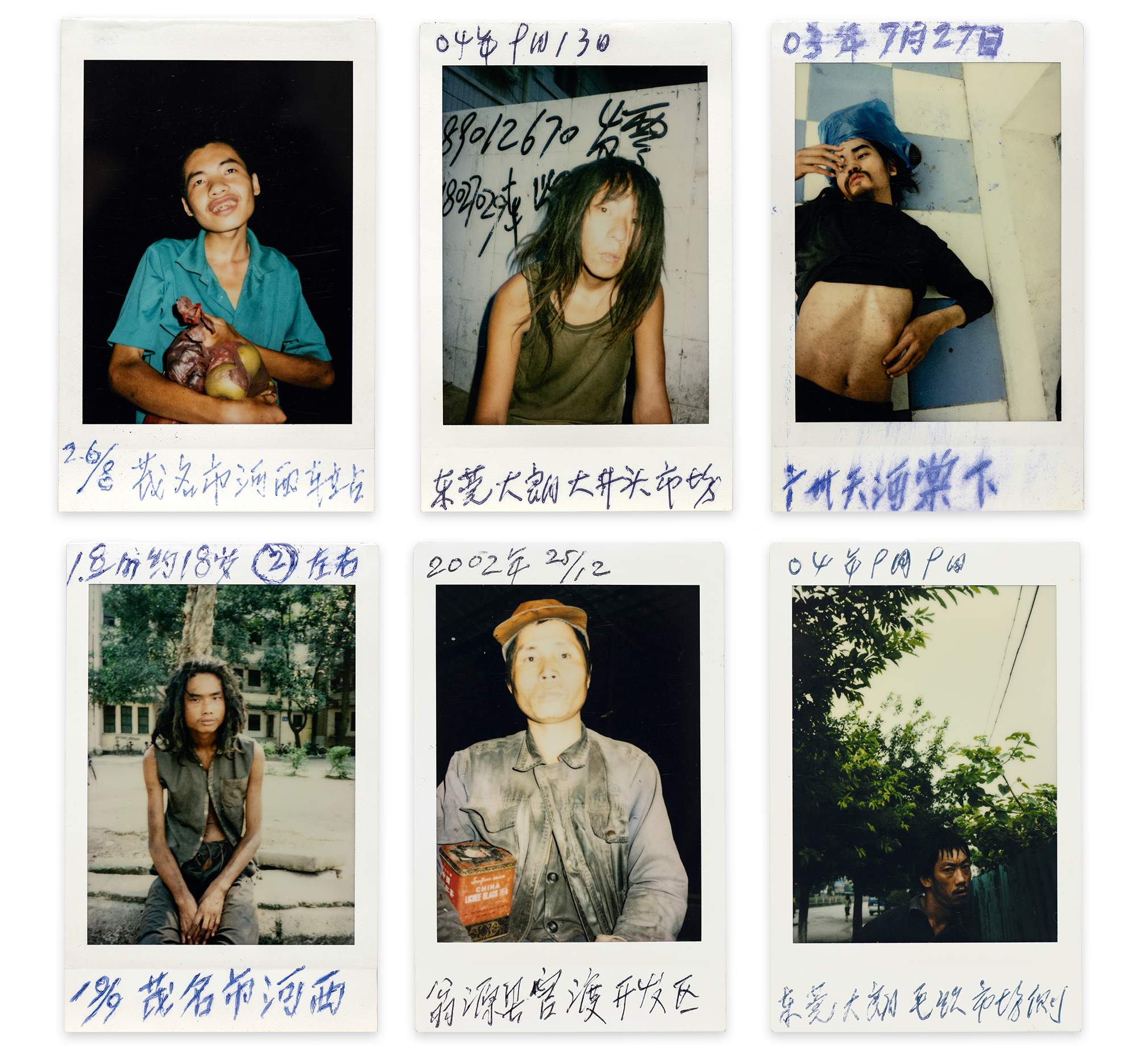

During these visits, she searched for Man-hon among the transient and disabled men she encountered. As Kwok explained to me, she would see an unhoused man, approach him, and, like some early Christian saint, brush the hair from his face. After verifying the man wasn’t Han’er (her son Han, in Chinese), she would take his portrait. The resulting Polaroids include, in her handwriting, the man’s name, the location, and the date. Your eyes fall upon the men’s shoulders, shrunken from hunger. Their necks seem too slender, their heads and often matted, overgrown hair loom over their torsos, grown tiny from want. Another man, smiling, looks comparatively nourished. His shirt and trousers are blemished with stains. His toes jut from his right boot.

“By photographing individuals who were not Man-hon, she was able to indirectly prove his existence through some method of elimination,” Kwok writes. However, these portraits did not prove he was living. They transferred his identity onto a substitute object, another man who might temporarily have contained the possibility of being Man-hon. Each portrait depicts someone not there, a vicarious memento mori. Her portraiture resembles few others because of her almost random relationship to those she photographed. Unlike a social reformer such as Jacob Riis, Ms. Yu had no investment in uplifting their plight. Their identities were almost incidental to her project, yet she documented them compulsively. Her unstudied repetition, obsessive seriality, and endless male subjects all recall efforts to index a specific population, but her portraits are not mug shots, ID cards, or a form of surveillance. She does not seek to exercise power over the “long hairs,” as Kwok called these men. Her figures look the viewer in the eye without any sense of shame, but also lack the inverted grandeur that suffuses, say, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936). Her Polaroids sometimes present young men roaming the nocturnal city, a genre whose closest Western correlative might be bohemian nightlife photographs, though the men here seem trapped in far more destitute straits.

The boy came to represent Hong Kong—a phantom languishing inside the foreign motherland.

Having systematically “cleared” one area, as Kwok put it, Ms. Yu went to the next. She began in Shenzhen with her husband, then gradually traveled alone through the provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, and Hunan, miles inland. One Polaroid isolates Mao’s famous slogan on a public building: “Serve the people.” The phrase can’t help but come off as charged, but Kwok describes Ms. Yu as “not really into political things.” Her portraits of the poor are only a by-product of her quest—but they hint at the underbelly of the Chinese economic paradox. No other country has lifted more people from poverty, yet China’s manufacturing boom relied on rural workers’ moving to urban factories and forfeiting their “iron rice bowl” of social benefits for a precarious life of contract labor. Tens of millions lost their jobs when state-owned enterprises in places such as Shenzhen conducted mass layoffs so that China could enter the World Trade Organization in 2001. Left behind was a generation of lost men—the Chinese lumpenproletariat profiled in Ms. Yu’s accidental visual ethnography. While unmotivated by anything as idealistic as transnational solidarity, she bridged the two Chinas—the declining former British financial center from which she ventured and the rising superpower that absorbed it—and created a point of contact between the lower classes of both.

Studio photographs sent to Ms. Yu by strangers claiming the young men pictured were Man-hon, ca. 2000–2010

From either side of this border came grifters, hustlers, and con men. Fortune tellers claimed they could reveal her son’s location, for a price. As Ms. Yu posted more flyers, she started receiving letters from mainland Chinese people who claimed they had found her son. “Seeing is believing,” as one of them wrote, so her correspondents often sent a picture—a studio portrait of someone they claimed was Man-hon. None resemble him at all. The men possess too much reality, their setting too little. In one portrait, a man wearing a camouflage jacket, his hair unkempt, his feet filthy, sits inside a brightly ersatz setting: a pot of plastic flowers beside him, a painted backdrop of an enormous cartoon candle. Does he exist in reality or in a cartoon universe of exuberant kitsch? His mouth hangs open, as if he doesn’t know.

In another portrait (featured on the cover of this issue), a man wears a three-piece suit and black loafers, an immaculate part in his hair. He crosses his legs next to a statue of a panting dog. Behind him stands a green Bob Ross–like painting of a European hamlet. While these portraits served as “evidence” of her son’s existence, they look aggressively, haphazardly constructed, as if someone condensed the elaborate staging and dramatized backgrounds of the photographer Wang Qingsong into a tacky prom photograph starring the poorest of the poor. Man-hon’s face, taken from that original missing person photo, sometimes appears photoshopped onto the male figure, creating a portrait of a half-fictional person and a “loop,” Kwok called it, back in time.

The letters asked for money. Others offered something else: speculative biographies of Man-hon’s future life. “I am doing well in Northeast China, and these two kind people brought me to a doctor specializing in neurology in Harbin City, who cured my mental illness,” writes one faux Man-hon in a 2005 letter. Ms. Yu tore up at least one letter. Then her innate sense of organization took over, and she taped it back together. “You never know who is in the photos,” Kwok told me, but he had a guess. He noticed certain figures reappeared despite the letters’ coming from different addresses, and concluded Ms. Yu’s pen pals were human traffickers.

“I won’t beat around the bush. I just want to help you find a brand-new son,” begins another. “His name is Tang Xiaolong, born on April 13, 1986. . . . He will make you love him like an object.” If Ms. Yu wanted to be introduced to her replacement son, another correspondent told her, she could meet him on October 20, 2003, beneath the dragon statue at Longcheng Plaza in Shenzhen, which was the first Chinese Special Economic Zone designed to attract foreign investment. When Man-hon disappeared, the city’s GDP was dwarfed by its Hong Kong neighbor ($22 billion versus $171 billion), but as Shenzhen became the so-called Silicon Valley of China, the two cities swapped places economically. Ms. Yu did not show up for the meeting. Kwok himself trekked to Longcheng Plaza recently, and his gleaming but somber photograph of the dragon statue seems to evoke the city’s intense gentrification and China’s own triumphant self-image—a perhaps too-glossy counterpoint to Ms. Yu’s raw, street-level eye. This photograph appeared in his 2023 installation at Hong Kong’s Para Site art center, accompanied by his deployment of geolocation to pin down Ms. Yu’s portraits of unhoused men and the studio portraits. His mapping suggested that she and her correspondents worked not far from each other, each photographing Chinese men who were not her son.

Courtesy the artist

Ms. Yu created more than three hundred Polaroids and received around one hundred letters, but later made more portraits, using other cameras and her phone, not included in Kwok’s project. She also says that four-fifths of the total material was stolen by a Chinese businessman who claimed he wanted to make a documentary about her. Kwok sees himself as a “researcher” or “investigator” behind a photographic practice “mostly driven by her intentions.” As he told me in his Cantonese-inflected English, “She really think what photography is.” Inverting the usual gendered division of art, she captured men living on the streets, while he photographed the domestic space of her apartment, her five rooster figurines peering out her window, their cries meant to scare off ominous spirits during Chinese funerals.

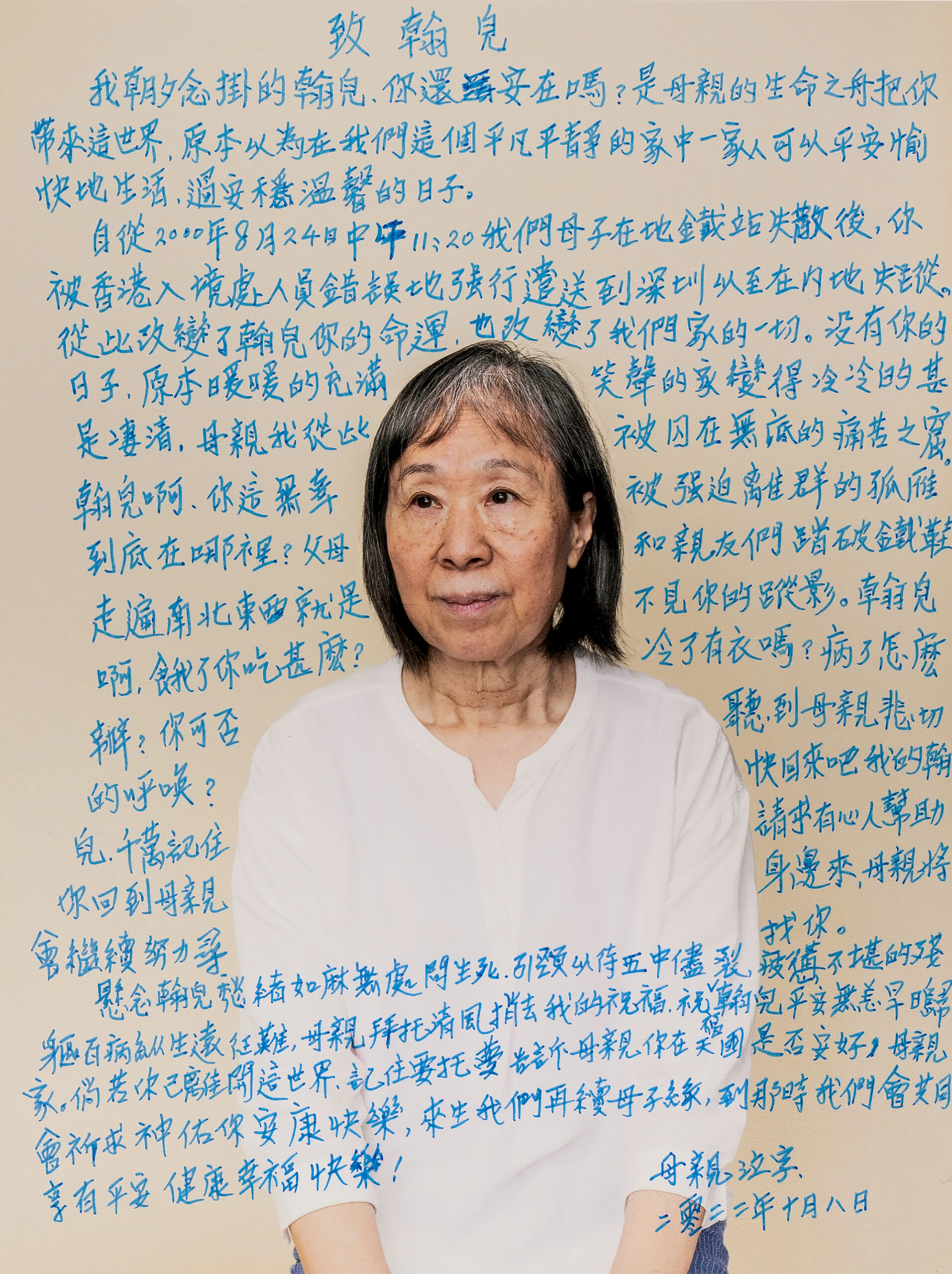

One day, Ms. Yu asked Kwok if he would create her portrait. She told him where to set up the camera and where she would sit. Just before Kwok clicked the shutter, she closed her eyes. When he asked why, Ms. Yu responded, “Photography is capturing a happiness moment.” Every day, she explained, she closes her eyes and dreams of her son. After he made a print, Kwok asked her to inscribe a message for Man-hon in the negative space of the background. To his surprise, she wrote out her statement immediately, as if it was some text she already knew. These are the words I say every morning, she told him, when I gaze out the window and look for my son. The first sentence reads, “Han’er, whom I miss day and night, are you still safe?”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories.”