From the Archive

An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory

For the past three decades, An-My Lê has used photography to examine her personal history and the legacies of US military power, probing the tension between experience and storytelling.

This interview was originally published in An-My Lê: Small Wars (2005), newly released in a twentieth anniversary edition.

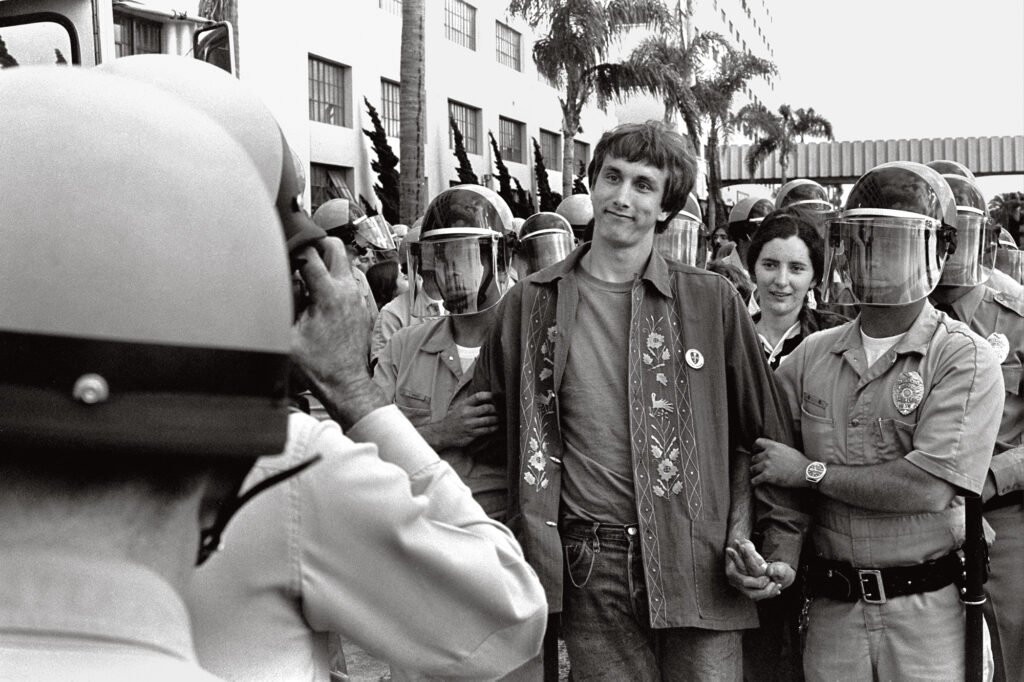

An-My Lê was born in Vietnam in 1960 and came to the United States as a political refugee at age fifteen. She received a grant to return to her homeland just after US Vietnamese relations were formally restored. Lê went back several times between 1994 and 1997, creating stunning large-format, black-and-white photographs, expertly printed in a middle-gray scale reminiscent of Robert Adams. These images do not address the war specifically, but rather represent Lê’s attempt to reconcile memories of her childhood home with the contemporary landscape that now confronted her. The war haunts the images in eerie metaphors: dozens of kites double as dive-bombing planes; crop fires and construction sites recall napalm and mass graves.

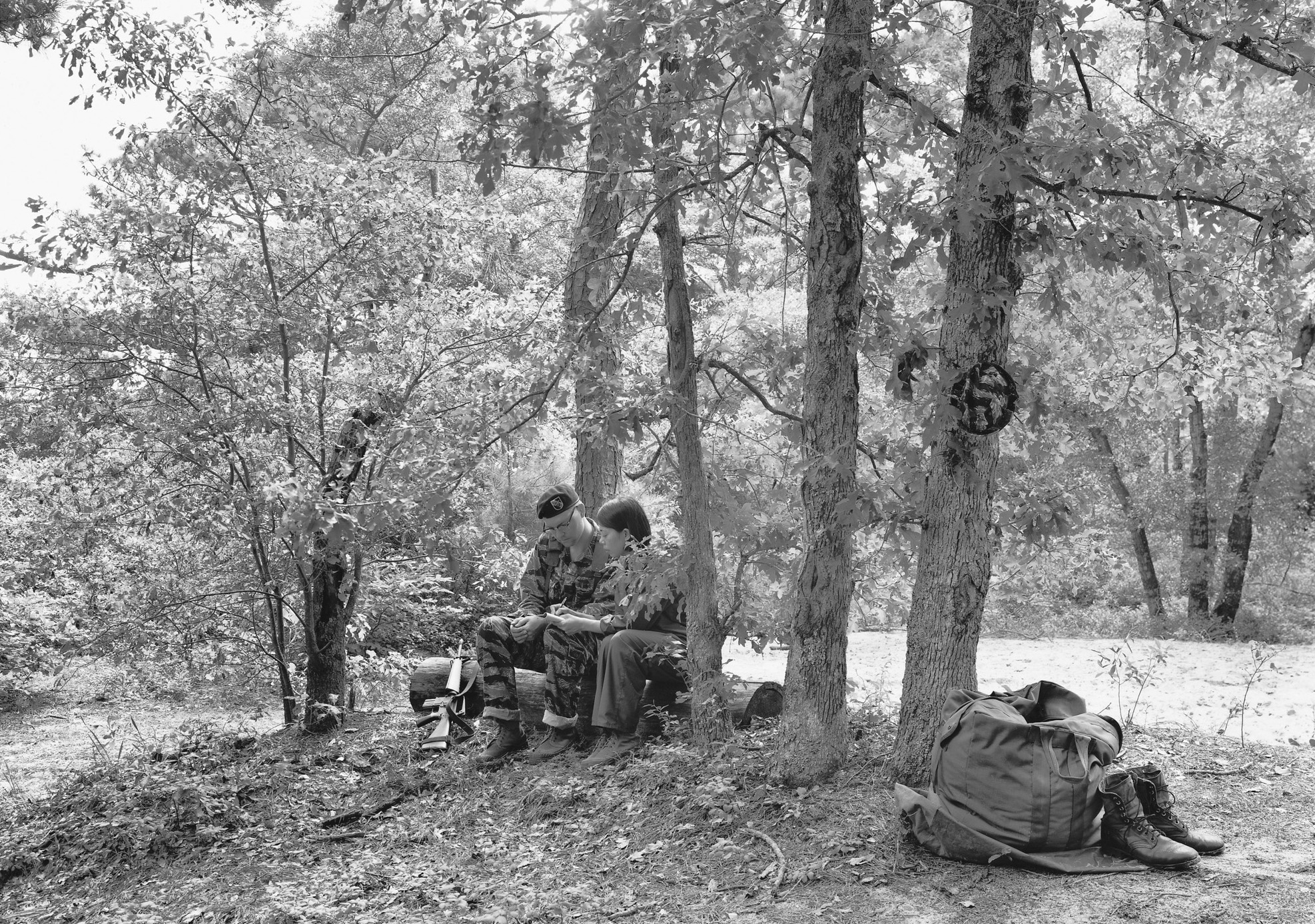

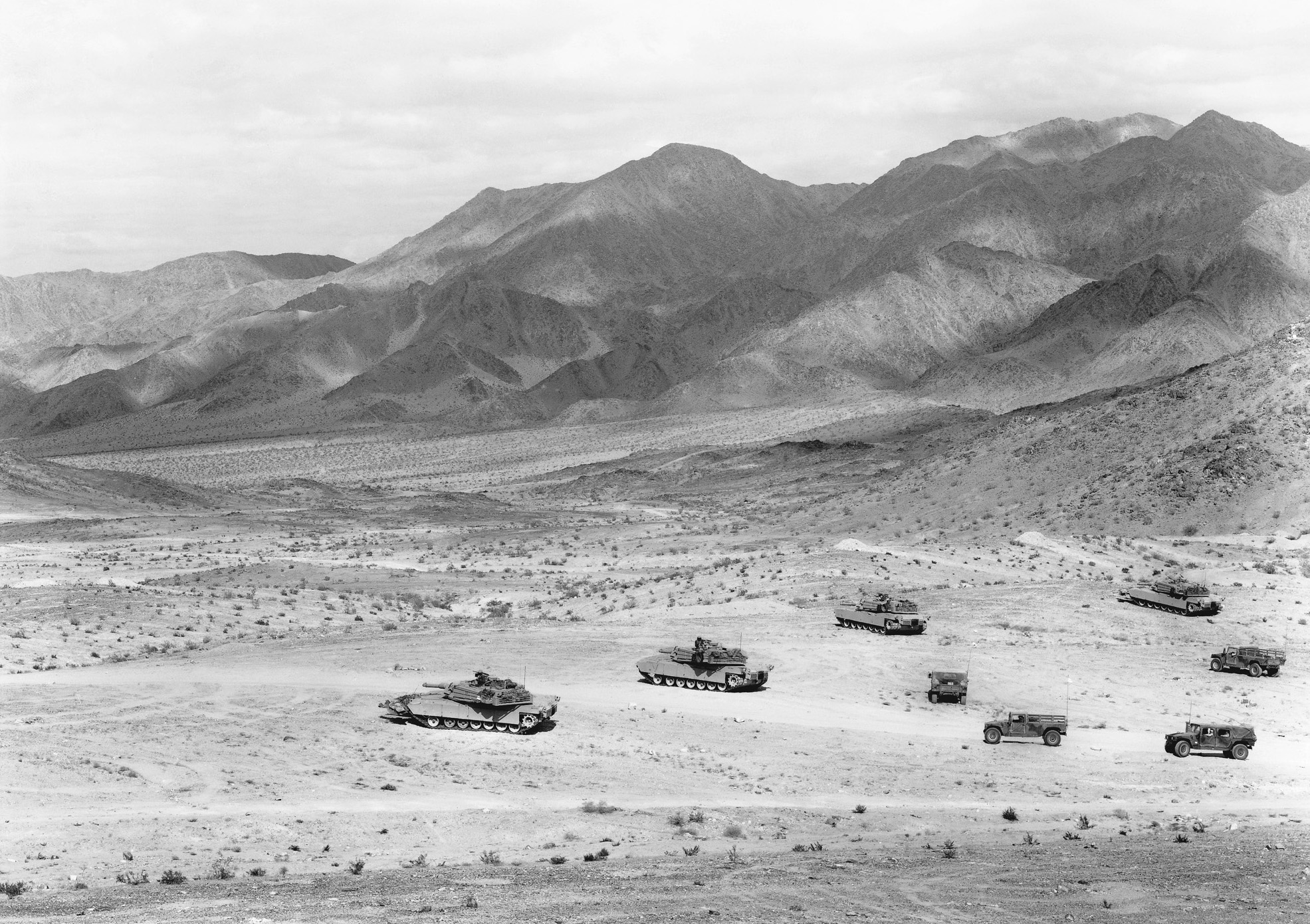

In 1999 Lê began working with Vietnam War reenactors in North Carolina who restage battles as well as the training and daily life of soldiers—both Viet Cong and American GIs. For four summers, she not only photographed but also participated in battles of the Vietnam War restaged on her adopted American soil. Relating to both documentary and staged photography, the work is aesthetically rigorous and conceptually challenging. Soldiers at rest give themselves up to portraiture, while battle compositions recognizable from classic war photojournalism possess the qualities of a dream. Most recently, Lê has photographed exercises performed by the US military in the American desert in preparation for maneuvers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Lê’s works elucidate the complicated nature of the aesthetics and spectacle of war. But perhaps the most intriguing conceptual component is Lê’s own relationship to the subjects and the landscapes she presents. —The Editors, from Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018)

Hilton Als: For Americans born in the 1960s, Vietnam, or, rather, the “issue” of Vietnam—the “problem” of Vietnam—was something that we always lived with: on television, in newspapers, and the rest. But we did not necessarily understand what “the war” in Vietnam was about. Can you provide a thumbnail sketch of the historical and political background of your country, and the effect its invasions—by the French, by Americans—had on you, your family, and your environs?

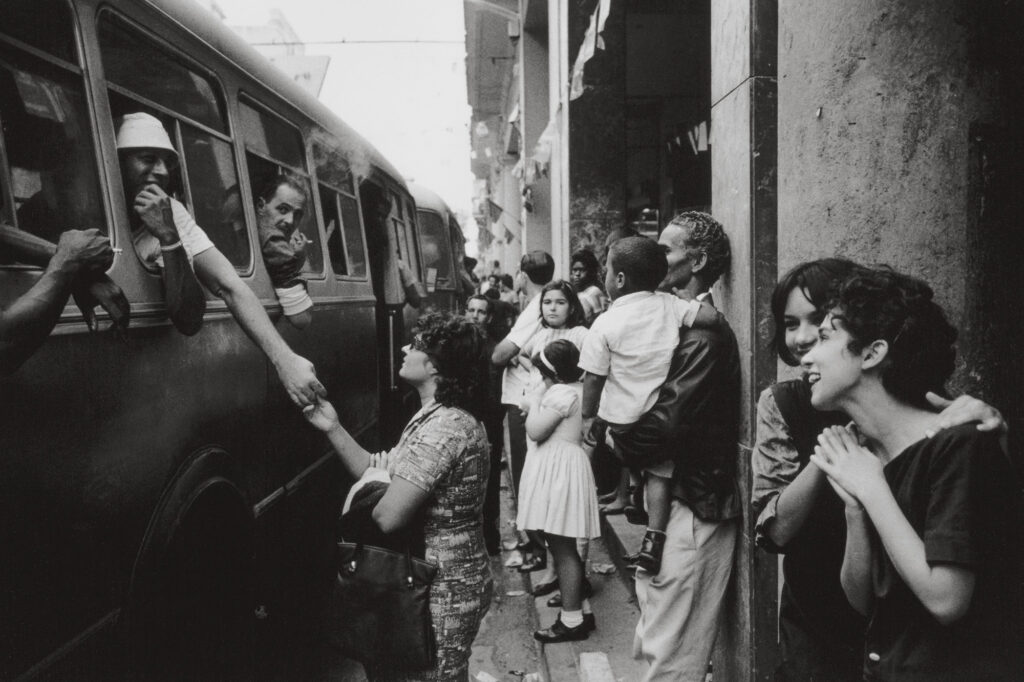

An-My Lê: My mother’s family—much more dominant in my life than my father’s—was from Thai Binh, a small town near Hanoi. They lived through the Japanese occupation and under Communist rule. My mother grew up in Hanoi but for higher education traveled to Paris in the 1950s. In 1954, while she was still in Paris, my grandmother moved to Saigon when the country was divided at the 17th parallel and the Communists took over the North. My mother met my father and married him in Paris, where my older brother was born. They eventually returned to Saigon, where I was born.

We lived through many political coups, years of fear and uncertainty, as the Viet Cong would shell the city randomly every night. War became a routine, something we accepted as part of our lives, until 1968 when the Communists attacked Saigon during the Tet celebrations. They took over the American embassy and the radio station behind our house. This offensive sent shock waves through the community. We all felt vulnerable. My parents decided we had to leave Vietnam to find shelter, even if it was for a short while. Fortunately my mother received a scholarship to work on a Ph.D. at the Sorbonne. We were able to move to Paris (my father stayed behind) and lived there for five years while she completed her Ph.D. We returned to Saigon in 1973, only to see the country fall to the Communists in 1975. We were fortunate to be evacuated by the Americans that April. In spite of our ties to France, my parents decided to remain in the United States because it seemed to offer more opportunities at that time. For better or for worse, my life and those of the last three generations of my family have been underscored by the complicated political history of Vietnam.

Als: Your photographs deal so specifically with ideas of landscape; do you work from your memory of the Vietnamese landscape to examine your feelings about it, or to imagine what its colonizers might have felt about it?

Lê: Over the years, disconnected from the place and with only a handful of family pictures available, I had come to construct my own notions of a Vietnam drawn mostly from memories, but also from photojournalism and Hollywood films. In 1994 when I returned for the first time, I realized that I was not particularly interested in reexamining contemporary Vietnam. Instead of seeking the real, I began

making photographs that use the real to ground the imaginary. The landscape genre or the description of people’s activities in the landscape lent itself well to this way of thinking.

My attachment to the idea of landscape is a direct extension of a life in exile. The sense of home has to do with the importance of food and location, and it is all connected to the land. Vietnam has always been (and still is somewhat) an agricultural society. Its culture and history are deeply rooted in its land. Growing up I did not know much of the country, actually not much outside of the capital and a few other large cities in the South, since it was difficult and unsafe to travel to the countryside during wartime. Especially when we lived in Paris and later in the U.S., I came to fantasize about this traditional agricultural way of life. Through folktales, legends, and many stories I heard from my mother and grandmother, I imagined a life that was truly magical but at the same time real and grounded—a life of hardship, working the land, with threats of war and disease but also the joys of living close to nature in a large, close-knit family.

Vietnamese society and in a way its people (especially in the North but partly in the South as well) have also been deeply scarred by years of immobilization and deprivation during the war and during the earlier part of the reunification. In the meantime, in spite of the destruction, the landscape seems to have recovered and, to someone living in exile, has managed to retain and exude that sense of culture and history that can signal that one has arrived home.

The idea of the landscape and its climate was also such an important topic when the Vietnam War was covered in military analyses, news reports, and Hollywood films. The word terrain was often mentioned: how treacherous it was, how the enemy was better prepared for it and had a greater advantage. Working with the Vietnam War reenactors I became fascinated by the significance of the landscape in terms of its strategic meaning. Every hilltop, bend in the road, group of trees, and open field became a possibility for an ambush, an escape route, a landing zone, or a campsite.

In spite of the influence of Vietnamese culture on my life, I am also a product of colonial attitude, having grown up in a Francophile home and then later having lived in France. Eugène Atget has been a great inspiration—not only his work, which brilliantly captures the notions of change and transition in a place and a culture, but his entire life and working process.

An-My Lê, Untitled, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam

Als: When did you begin your career in photography? And why?

Lê: It began by chance. I never felt I had a calling for anything in particular but was fairly good in the sciences, so I chose to study biology in college in preparation for a career in medicine. I was not accepted to any of the medical schools I applied to in my senior year, and it was suggested that I do biomedical research, publish, pursue a master’s degree in biology, and reapply. While completing a master’s at Stanford University, I wanted to take a drawing class to fulfill a nonscience requirement. It was full, so I chose photography instead. To my surprise, the class completely took over my life. If I was not photographing, I was in the darkroom printing until late. I loved every minute of it.

What drew me at first was simply how the camera gave me license to go out and discover more of the world; it taught me about people and places and about myself as well. The immediacy of responding to a situation when you snap your photo, the opportunity to be more analytical later when you edit the pictures, and the blend of the intuitive and the cerebral was very satisfying. Whatever a calling could be, it seemed to me that this was it.

In 1986 I moved back to Paris, where I floundered for a few months until Laura Volkerding, my teacher from Stanford, arrived. She came to document the casting of Rodin’s Gates of Hell that had been donated to Stanford by Gerald Cantor. It was to be cast using the lost wax method at a foundry that belongs to a guild of craftsmen called the Compagnons du Devoir du Tour de France. The guild dates back to the Middle Ages and is comprised of various métiers: metalwork, masonry, stone-cutting, and carpentry/woodwork. These craftsmen were responsible for the construction of most churches and cathedrals in France. Now they do a lot of restoration work.

It turned out that the guild needed a staff photographer, and Laura referred me. I spent the next four years touring France and working for them. I was completely unprepared for the demands of this job; I quickly learned how to use a view camera on my own, how to use color film, how to light a space. I underwent a lot of trial and error. It was a great opportunity for me to travel and learn about the art and architecture of France, but more importantly, working for the guild deeply affected the way I saw things and represented them photographically. It was always about seeing clearly: showing the curve of a stairwell in an unencumbered way, the texture of this marble or that wood, drawing the volume of a vault in the most readable way. I also learned to respect the materiality of things (the nobility of stone, metal, and wood). I developed an appreciation of all things well made and a love for everything about the tradition of the craftsman and his work.

I moved back to the U.S., to New York City, in 1990. I finally realized that I did not want to be a commercial photographer and applied to graduate school. I then went to the Yale School of Art for my MFA. That’s when I began to grapple with the scope of a possible life as a visual artist.

An-My Lê: Small Wars

60.00

$60.00Add to cart

Als: After you began photographing, did you immediately establish long-range plans in terms of what you wanted to accomplish with it, such as your studies of the reenactors in “their” recreated Vietnam, or is it all a process of discovery?

Lê: It was all subconscious. I am rather amazed at how the three projects have come together as a sort of trilogy. Going into a project, I never know the photographs I will end up making. It is a process of discovery, and I try to stay as open-minded as possible. For me it is first about learning something about the world, about myself. It is a little frightening starting a project in such a way and not feeling prepared, but so much of it is about problem solving. I am always asking myself what it is I am trying to find out about the situation, about the people: What does it all mean in terms of a cultural and historical context? What are my personal issues here? What is the point? Is it worthwhile? What kind of photographs could attempt to broach and perhaps begin to answer those questions?

The Vietnam project happened in 1993 after graduation from Yale, where I had been encouraged to do work that was more personal and autobiographical. The U.S. was loosening its diplomatic and economic relations with Vietnam. I saw the opportunity to return to Vietnam, which is something we never thought we could do when we left in 1975. The question of war was not central to the photographs I made in Vietnam. Only at the conclusion of this project did I feel ready to tackle that issue head-on. I had to also ask myself: how do you address something that has happened so long ago? I felt stumped; other than working with press images or trying to memorialize the event, what could I do?

Some of what I did in Vietnam, where I learned how to place people in the landscape, prepared me for the subsequent series. I learned that it is all about scale. How far back can you go to get a great drawing of the land, while still being able to suggest the activity of the people?

Als: How did you find out about the “reenactments”? And what was your first response to them? Did you have to go through a great deal of bureaucratic rigmarole to gain access to photograph?

Lê: I had heard about these small, low-key groups of men who reenact the Vietnam War. After some research on the Internet, I found one group based in Virginia and contacted them. It was smaller and more exclusive when I first worked with them than it is now. Gaining an invitation to the first event involved a lot of back and forth emailing with the founder. Once I was there, it became a lot easier because it was clear I wanted to help contribute to the event as best as I could while making my photographs.

Als: Did you actually become involved in any of the war games that you documented?

Lê: Yes, that’s the requirement for attending the events, which last three days. The reenactors are obsessed with re-creating a situation that is seamless. So it is crucial that everything—from the erection of Viet Cong villages and GI firebases to a haircut and the smallest details in a uniform—be of the period. To fit in I often played a VC guerilla or North Vietnamese army soldier. I did what I needed to do to find the right VC uniform, sandals, rucksacks, and hammock. To go on the GI side, I would become a “Kit Carson” scout, a turncoat who would inform the Americans.

The reenactors truly enjoyed having me there. I added to the authenticity of the event, and they would often concoct elaborate scenarios around my character. I have played the sniper girl (my favorite—it felt perversely empowering to control something that I never had any say in). I have been the lone guerilla left over in a booby-trapped village to spring out of a hut and ambush the GI platoon. I have played the captured prisoner.

Initially I was terrified at the prospect of spending three days with these unknown men on a hundred- acre private property ten hours from New York City. My friend Lois Connor accompanied me. It turns out the reenactors are straightforward, conservative men who are so dedicated to this hobby. It’s an obsession for many of them—an obsession with collecting and trading all the paraphernalia, meshed with an interest in military history. Reenacting events are an opportunity for them to put their stuff to use, meet other men who share their interest, and live in a kind of virtual reality or travel back in time, all while having an adventure with their buddies.

From many conversations, I also learned that their interest in the military and in Vietnam stemmed from complicated personal histories. These men came from all sorts of professions. A few had been in the military, but rarely did they have experience in a combat situation. Some had missed their calling for the military and were steered by their parents toward law school or business school; some had

lost a brother in Vietnam. I met at least two men whose fathers had distinguished themselves in combat in Vietnam. It seemed that many of them had complicated personal issues they were trying to resolve, but then I was also trying to resolve mine. In a way, we were all artists trying to make sense of our own personal baggage.

Als: How did you develop the topic of the third series?

Lê: In 2002 and 2003 the U.S. was gearing up for the war in Iraq and Afghanistan just as I finished working with the reenactors. I was extremely distressed the day the war began in March 2003. Strangely enough, my heart did not go out immediately to the Iraqi civilians, but to our troops. I first thought of the scope and impact of war on them and their extended families. I am not categorically against war, but I feel the decision makers and policy makers have no idea how devastating the effects of war can be. Remembering my own experience, I also felt completely vulnerable. War just seemed unreasonable and unjustified in this case.

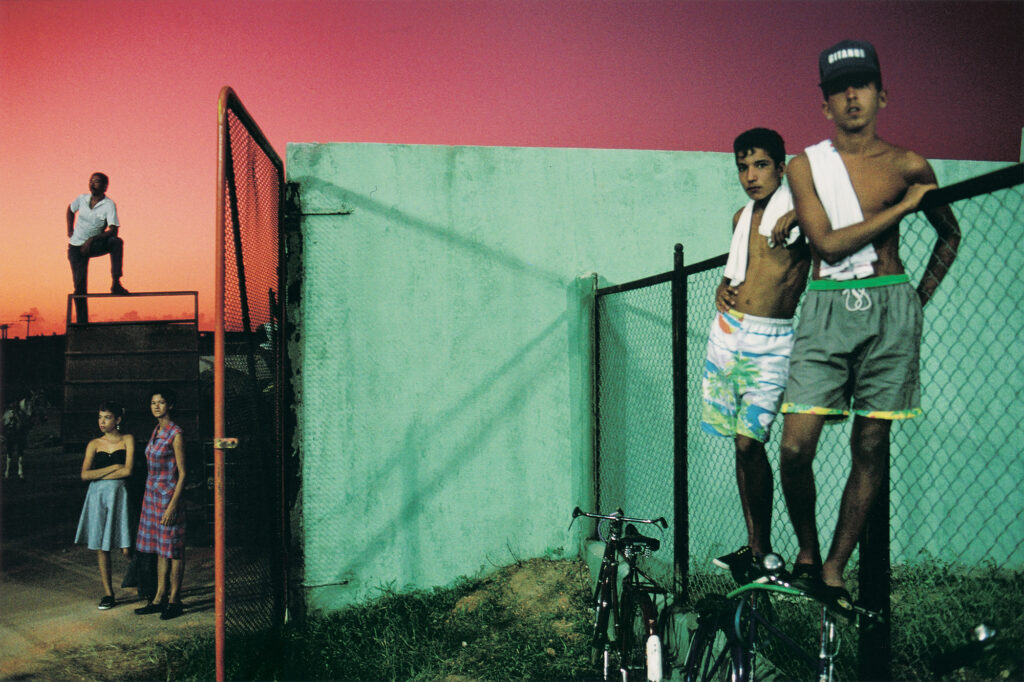

Trying to make sense of all this, I decided I had to find a way to go to Iraq. It was, unfortunately, too late to become embedded. I came across a photograph of the Marines training in the California desert in 29 Palms that looked just like parts of Afghanistan and Iraq. I immediately knew this place held great potential for a new project. Working there would follow with the idea of the reenactment and training for something. I was also drawn by the concept of simulations that are once removed but allow one to see and understand the real thing with clarity and perhaps more objectivity.

Once I began photographing at the Marine Air Ground Combat Center in 29 Palms, it became obvious that my pictures stand in complete opposition to combat photography. We are dealing with parallel subjects, but the outcome—the meaning—is completely different. In the case of combat photography, the die is cast. The photographer is thrown into a conflict where his work is about capturing the action or the aftermath. Chaos, he horrific violence of the moment, and the obvious risk incurred by the photographer in this situation all play into producing an image with a brutal if not blinding immediacy. Conversely, working with the military in training allows for breathing room. What jumps out for me is the way in which the magnitude of the firepower used—from artillery weapons to mortars, C-4 explosives, and air-delivered bombs—and its destructive potential, becomes muted and transformed as it is photographed in these exercises in the middle of a tranquil desert. One can then step back and ponder the larger issues of war. For me the question is not only are we militarily ready, but also are we politically, morally, and philosophically prepared? No, we are not. This project is an impassioned plea for a much-needed consideration of the consequences of war.

Als: Have you looked at a great many war photographs? And do you agree with many photography critics when they say that photographs of war “depersonalize” pain? By working with “staged” coups and so on, does that distance Vietnam for you?

Lê: I am a great admirer of the nineteenth-century war photographers, but I also respect the more contemporary ones: Robert Capa, Larry Burrows, James Nachtwey, Gilles Peress, Tyler Hicks. I have studied the work of many North Vietnamese combat photographers. In a way I feel closer to them and the nineteenth-century European photographers because of the importance they give the landscape in their work.

I do think the current photos of war from Iraq and Afghanistan (except for the Abu Ghraib pictures, which were not made by professional photographers) are a lot more tame and feel more glossy than anything ever made in Vietnam, but it’s also true that our hearts are colder these days from having been bombarded with one agonizing and horrific picture after another. In the end I think it is the cumulative effect of the images over time that will have as much effect on us as the single image of the young Vietnamese girl burned by a napalm bomb.

What are the effects of war on the landscape, on people’s lives? How is war imprinted in our collective memory and in our culture?

The more contemporary photographs that capture the immediate moment certainly convey the devastation and pain, but they are usually so horrific one has to turn away in shock—they go more to your gut than to your head. In the end these photographs certainly remind us we are at war, but how thought provoking are they?

I am more interested in the precursor to war and its psychic aftermath. There is something about addressing the preparation for war or the memory of war itself that allows one to think about the larger issues of war and devastation. Again, how prepared are we? And what are the effects of war on the landscape, on people’s lives? How is war imprinted in our collective memory and in our culture? How does it become enmeshed with romance and myth over time (i.e., for Hollywood and for the reenactors)? My concern is to make photographs that are provocative in response to the reality of war while challenging its context.

Als: Of course, all photographs lie. I consider pictures to be metaphors for actual events and the people in them. For me, photographs capture something—an essence—of an event or a person, but selectively. Given the pictorial and emotional scope of your work, how do you set about capturing such a large portion of our collective political history?

Lê: Great landscape photography has a literal but also a metaphorical scope to it (Atget, Robert Adams, etc.). There is something about seeing people’s lives (or the suggestion of it) splayed across a landscape that can be breathtaking and unforgettable. There is no escaping the specificity of photography, but I aspire to achieve a certain lyrical objectivity. It is more about patterns of behavior than the specificity of it, which perhaps allows for a larger understanding of history and culture. August Sander and Judith Joy Ross manage to do this through portraiture. Here it is landscape photography that gives me that opportunity. It allows for descriptive possibilities. You can ascribe character to a landscape; you can suggest its usage. It is like a stage and, most importantly, I try to not let the people and their activities completely take over.

Als: Why do you shoot in black and white? And what kind of camera do you use?

Lê: I always consider all possible tools at the beginning of a project (color or black-and-white film; small-, medium-, or large-format cameras). But so far, the 5-by-7-view camera has been my tool of choice, in spite of its inconveniences. It provides a great large negative full of details. It allows for a certain clarity and descriptive sharpness. Above all, in an image from 5-by-7 negatives or larger, one can sense the volumes of air moving between things and inside spaces. I tend to prefer black and white because I am very interested in the way things are “drawn.” This is much more apparent in black and white, where the palette is reduced simply to black, white, and various shades of gray. The world as seen in black and white also feels one step removed from its reality, so it seems fitting as a way to conjure up memory or to blur fact and fiction. Most of my memories of the Vietnam War, aside from what I witnessed firsthand, derive from black-and-white television news footage and black-and-white newspaper images.

The 5-by-7 view camera is very clunky because of its size, weight, numerous accessories, and the need for a tripod. You can’t work that spontaneously. All shots have to be somewhat premeditated and directed, especially those involving people, because of slow shutter speeds and delay between framing the image and closing the shutter/cocking the lens/exposing the film. A lot of this accounts for the pictures in all my projects seeming staged. There were situations where I had to photograph what was in front of me, but there were also times when I had an idea and went about constructing the scene from scratch (using the setting and prop of choice, choosing the people, and directing them). Working this way—either planning something from scratch or anticipating something before it happens—feels much more cerebral. We often say that photographers hide behind their cameras. In a way the view camera has provided me with multiple shields from the painful memory of war, while allowing me to come as close as possible to try to understand it.

Als: Some of your pictures look like film stills; have you looked at a lot of narrative and documentary films about Vietnam in preparation for your work?

Lê: If they resemble film stills, most are more in the vein of the establishing shots—those that situate everything. I have always looked at Vietnam War films. (Well, only starting in the mid-eighties—it was too soon and still somewhat too traumatic before then.) I was interested in seeing how something that I knew so well, something that affected me so deeply, was portrayed on screen. Watching these movies was also the only opportunity to get a glimpse of “Vietnam.” Even when another country or Chinese actors were used as stand-ins, any suggestion of the country, its life, and its people satisfied my curiosity (and tempered my homesickness and yearning). The Anderson Platoon, a documentary by Pierre Schoendorffer, and of course Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Casualties of War, Platoon—the first three are my favorites. More recently, I have seen these movies with a completely different interest in mind. I am interested in the Vietnam of the mind. It’s fascinating to me how all these other countries (Thailand and the Philippines mostly) are stand-ins for Vietnam and how the landscape has become a character.

I have been paying attention to how the cinematography is used to conjure up the past. The idea of the period piece is an interesting conceit. Many people find the activities of the Vietnam War reenactors very disturbing. Comparatively, Hollywood’s obsession with the Vietnam War and its numerous, painstaking “reenactments” on film seem completely reasonable. For me the fascination lies in the dialogue these two worlds establish between experience and chaos versus memory and storytelling.

These days, young Americans are first introduced to the subject of Vietnam, the Holocaust, or World War II by movies like Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, or Apocalypse Now, and only later (or maybe never) will they learn the hard historical facts in textbooks in a classroom situation. From the start, there is a blurring of fact and fiction that’s fascinating.

I draw my motivations for these projects from personal memories and from both a fascination and an aversion for anything that has to do with war and destruction, for the military, paramilitary fringe groups. Mix into that an interest in mediated images in popular culture—all of these influence the way my pictures look: they could be as much about my memory of GIs walking down Tu Do street in Saigon as an echo of the depiction of the Air Cavalry machos in Apocalypse Now. I consider my work an inquiry into the literal representation of things vs. depictions that live in popular imagination.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Als: How did you feel at the end of these various projects? Did you feel as if you had “come home” in a sense? Has this work helped you deal with your origins?

Lê: It’s interesting that you ask about “coming home.” I’ve been obsessed with that idea because it applies to the type of fieldwork I do as a photographer as much as it is relevant to the experiences of the refugee and the soldier. Ambiguity and contradictions—the conflict between expectations and memories—these are all built into the experience of coming home for a refugee, for a soldier (whether from a real or virtual battle), or even for a photographer. Whether it is a childhood abruptly ended or a violently murderous week-long siege during the battle of Khe Sanh, some of us are confronted with these intense life experiences. They’re defining experiences that echo throughout one’s life. Whether coming home, returning to the country of origin for the refugee, going back to civilian life for the soldier, one is compelled to construct a story for oneself and hopefully come to terms with what happened. In attempting to construct a coherent narrative, one must negotiate a contentious and sometimes contradictory terrain, reconciling one’s own experience with other people’s ideas of it and against general expectations. It’s about understanding how one’s experience fits into the larger scheme of things and finding a personal equilibrium within that.

And as a photographer, there’s another layer—I have a different relationship to memories than the refugee or the soldier because through the work, there is potential for tangibility. I am the type of photographer who is interested in the way things look and in letting that be my major story-telling device. In that pointed moment it allows one to raise pertinent questions and to ponder the larger issues involved.

Crudely, my work is about reconciling what I thought I was getting myself into and what is actually revealed to me in the field. It’s not about taking a specific stand, or dignifying something that is important to me—nor is it about exalting a specific cause I’m committed to or exploring a subculture in depth. I’m satisfied in simply addressing these subjects: Vietnam, the military and the glamour of war, cultural and political history, and small subcultures. Photography becomes the perfect medium for conjuring up a sense of clarity (if not necessarily the truth) in the midst of chaotic and polarizing subjects.

This interview was originally published in An-My Lê: Small Wars (Aperture, 2025) and anthologized in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).