Interviews

Ari Marcopoulos on the Essential Art of Zines

The inveterate zine-maker speaks about his artistic practice, learning under Andy Warhol and Irving Penn, and why “everything is worth photographing.”

Ari Marcopoulos is an inveterate maker of zines. Often self-published or created in collaboration with independent publishers, his DIY-aesthetic creations function as sketchbooks, diaries, installation spaces, and means of processing daily life. Marcopoulos’s latest volume, Zines, is the first overview of his publications. Beginning in 2015 and presented chronologically by year, the book features key zines—including previously unpublished works and some made during the pandemic, when Marcopoulos worked primarily on the screen to make PDF zines. Marcopoulos recently spoke with Hamza Walker about the role of zines as an essential part of his artistic practice.

Hamza Walker: Could you speak about the difference between the printed zine and the PDFs? What’s their relationship? Don’t the PDFs go through the same process of making them, whether they’re printed or not?

Ari Marcopoulos: Yes. The PDFs really started because of thinking about the vertical or landscape book. Usually when you make a zine, you have an 8.5-by-11-inch paper, and you fold it in half, and then you have 8.5-by-5.5-inch. It’s a vertical format. I wanted to work against that. I started by creating the container for the images, and that container was a 9-by-11-inch landscape format, sideways. So, I made a PDF, which I thought I could print myself, but the 9-by-11-inch format was too big to print at home. And the copy shops were all closed. After I made the first one on my computer, which was too big to print, I was like, Okay, so, what do I do with it now? I decided to email it to a few friends, because everything had ended once the pandemic began. You weren’t seeing other people anymore. I figured, Well, instead of writing a letter, why don’t I just send them these images, this PDF that I put together? I got really beautiful responses. I sent some to Pierre Huyghe, who had moved to Chile. He had been living in Brooklyn, and they moved right before the pandemic, he and his wife and child. He replied, “Oh, I really miss Brooklyn. Thank you for sending this. It makes me think about my walks in town.” Actually, a lot of the zines featured in this book are made as a gift, like the ones I sent to Pierre. Usually, it’s people around the neighborhood that I photograph, like at the barber shop, or my neighbors, and then I give them a print. One weekend, there were two men that I didn’t recognize sitting on the steps down the street, but they looked related.

My neighbor Gary had told me it was his brother’s birthday party. I asked, “Are you guys here for the birthday party?” And they said yeah. I asked, “Do you mind if I take your picture? I’m a friend of Gary’s.” And they’re like, Yeah, take our picture. I took it, and then went on my way. When I came back, there was a third guy, so I stopped again and said, Oh, there’s another person, I should take another picture. All through the weekend, as I passed by, there were different people, different characters. I photographed them whenever I saw someone different. When I got the film back, I looked at the faces, and there were fourteen different people. So, I put together a zine. I printed something like twenty copies, and slipped fourteen of them into the mailbox for Gary. When I went to the barbershop next to get my hair cut—this is pre-pandemic—they said, “Gary brought in the book that you made for him.” He had brought it in to show to them. Now all the guys, when I see them, they’re like, Oh, you made that book for us! That exchange is part of my practice.

Walker: Which is a very beautiful ethos, to think of the relationship to the sitter, however casual. The sitter as recipient—the sitter as the audience for the work. It completes a full circuit. If you take the picture and put it on the wall of a gallery, it’s a very different means of distribution or circulation.

Marcopoulos: You make the work, you have your ideas about it, and it can live like that, but it’s really only finished if it’s circulating outside of yourself and there’s a viewer involved. Because the viewer finishes the work. Just recently, I bumped into Gary, and I hadn’t seen him for a while. I said hi to him, and I took his photograph, because whenever I bump into him, I take his photograph. Then he told me, “Oh, I have to go to the funeral of my brother.” I said, “Oh, your brother? I’m sorry. I’m glad I took his picture.” And he says, “Yeah, I am too.” Every relative that was on the stoop that day has a copy of that zine.

I always believe that the images that I work with are shared experiences, where the viewer might recognize something in their own life.

Walker: It’s a zine, but …

Marcopoulos: It is a book. And it can be a very beautiful book.

Walker: The nature in which a zine is a book, in terms of how it is handled and its reception and how it is held, formally, is interesting. Photography’s always had this promise of being able to make multiple prints and then distribute them. It seems like you’re fulfilling that process through the zine rather than the print itself. You could give somebody a photographic print, which perhaps goes in an album or could be framed and put on a wall. But that’s something different. The book or a zine is cinematic, is in sequence. It’s another kind of intimacy. The wall is public, the book is private.

Marcopoulos: Oh, it’s definitely a private experience. A book is basically just held at arm’s length. It’s why I often believe some books are too big. To have a photobook that holds and reads like a novel is really quite intimate, you know? Of course, I do exhibitions. I put things on the wall—large things on the wall. Although most of the installations that I’ve done in the last ten years or so have been often lots of photographs, quite small and also sequenced quite tightly together. But it’s still very different. When you have a sequence of photographs on the wall, you have an overview right away. With a book, you can look at it backwards, start in the middle, anywhere. But still, you’re always dealing with the page—where the page is open, that’s what you’re dealing with.

Walker: Right, one spread at a time.

Marcopoulos: And to share it with someone, you actually have to sit quite close together. So often in photography, one thinks about the single image. I started to think more cinematically, about how a sequence of images becomes a more layered way of looking at something.

Walker: I guess the bigger question is, how much does the zine structure inform your photographic output? In other words, when you work and you’re taking pictures, are zines the logical destination for your work?

Marcopoulos: I believe that any image I make can potentially end up in a zine. There are certain images in this book which might not have ever made it into print otherwise. The content might be a bit more personal, but I always believe that the images that I work with are shared experiences, where the viewer might recognize something in their own life. And then maybe, in the zines, there are things that might shed new light on something that is very particular. I have very particular interests that weave through. For forty years, these things come back through the work. When am I going to stop photographing ’70s muscle cars? Probably never. Or when am I going to stop photographing trees? When am I going to stop photographing people? Those are my recurring themes. And then there’s also the struggle to get away from that. Opening up new roads for yourself. I’m just saying, Look, here. Not because every photograph I’ve published is a masterwork. They’re just things that I saw.

Walker: I like what you were saying about how your interests are woven throughout. At any given instant, a muscle car could appear. You’re always making pictures. That’s a given. So, you wouldn’t make a zine of ’70s muscle cars. But they will recur.

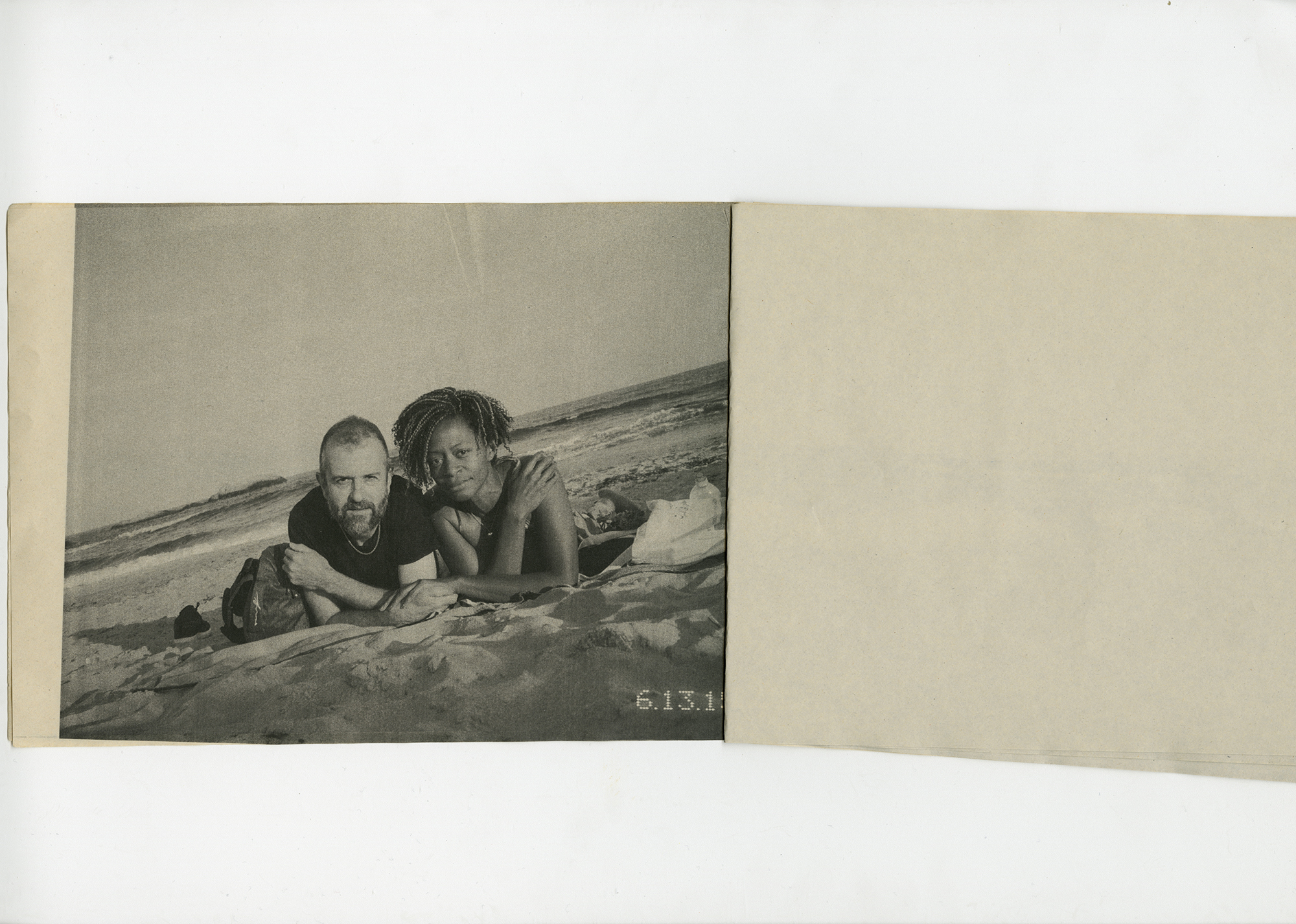

Marcopoulos: I would have to go through my archive and look for every muscle car picture and then start putting them all in a row. That’s just not how I work. The way I work is more about, if I go for a walk today, am I going to see a muscle car? Possibly not. Now, what I might do is maybe I would go now and photograph the car and I would make a zine of that. There’s a zine in the book called September/October/November, and it’s just pictures I took in that period of time. And it happens to be that in those months, I went to Paris and to Beirut. And I was in New York in between. I don’t take a lot of pictures every day, so all of those cities might be on one roll. That is kind of how zines are. I don’t very often work chronologically. But the zines are marked by a start date and an end date. I started using a camera that has a date stamp that you see in a lot of these photos.

Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (“Closed” zine/launch edition)

65.00

Walker: What’s beautiful is that the few thematic zines that are very discrete do not feel anomalous. They feel like, Oh, yeah, it’s a possibility. But they’re not the drive. I like that you brought up the issue of the personal. It’s personal but it’s not personal. There needs to be something to which the viewer can relate. The viewer can relate to a picture, not necessarily because of what it discloses, but because of their own experiences. There are also some individuals in the photographs that are recurring. And those pictures come out of friendship and love.

I’m also curious about the role of Robert Frank and June Leaf, for you. Could you talk a little bit, maybe, about that relationship and those pictures?

Marcopoulos: I met Robert a long time ago, but I always felt that going up to ring the doorbell or hanging out wasn’t something I could do, because he’s this icon, of course. But one day a friend of mine went over to drop a sandwich off for them. And said, “Come with me.” And I said, “No, it’s okay. I’m not coming.” He said, “No, Robert knows you.” That was in 2018 or something.

Walker: So, you struck up a friendship with Robert Frank rather late.

Marcopoulos: Well, I’d met him before, but didn’t really hang out. I went to his opening at the National Gallery in Washington, but the reconnection happened much later. I took a picture of June’s arm and showed it to her. She loved it. And then Kara came up, and June said she admired Kara’s work. And so I told Kara, “Come by and meet June and Robert.” And Kara was a little bit [sighs] “Okay.” But June and Kara hit it off pretty well, as you can imagine. Both are unique, out-there thinkers. So, we started seeing them more often. We had a ritual that we would go every Sunday evening and we would have dinner. Sometimes I’d talk to Robert about photography, but more about his life. His memory was somewhat fading. I would ask him questions about his youth. He would tell me some good stories. Robert and I both moved to New York around the same age. That was something that we had in common that we sometimes talked about, leaving the comfort of a country where you know everything, to a place where you’re new and that is distinctly more exciting than where you came from [laughs]. New York City, you know.

Walker: When you first came to New York, you spent two years printing for Andy Warhol. How did you get that job?

Marcopoulos: I moved to New York in 1980. I thought that in order to make money with photography you had to be a fashion photographer. I had to find a job as an assistant or something. I did some freelance assisting, but the first job I landed was printing 8-by- 10-inch photographs for Warhol, black-and-white prints. I worked in a darkroom off-site, not at the Factory. I printed, on average, seventy 8-by-10-inch pictures a day, 350 prints a week of his pictures. He was incessantly taking pictures. He would mark the contact sheets, and I would print those. Thousands of them. I did that for almost two years. I saw all the pictures that he took. I saw all that he saw when he was traveling. I would see pictures of Joseph Beuys, of Berlin, of Beijing, of whatever. Wherever the fuck he went, I saw pictures of it. You know, he would go to some rich person’s house and he would photograph the table with the family photos on there. It was like a diary. He just photographed everything. He loved celebrities and got to hang with them. Signs, people, people’s houses. Before I moved to New York, I had worked at a camera store, where people would bring their film to be developed. So, I also had the experience of seeing everybody’s pictures from the town I grew up in every morning when they came in. And that was kind of like Warhol’s pictures. I saw all the pictures.

Walker: What influence do you think that had on you?

Marcopoulos: Andy Warhol had an influence on me even before that, via his films and his artwork. But yes, working and printing Warhol’s pictures had a profound influence on me, although my camera shop job was maybe equally profound. I learned that everything is worth photographing. I learned that you should never say, Why would I take a picture of this? After I stopped working for Warhol, I worked for Irving Penn for two years. Then, I worked for the most restricted, anal-retentive photographer that you can imagine. Everything was controlled.

There’s no spontaneity in Irving Penn’s photographs. It was very technical. The influence of working with Penn was that I started to understand how light works, what you can do with light—what you can do with artificial light, but also what you can do with daylight. I started understanding how composition can emphasize a shape or can steer the eye. When I look at my work, I can see that even when I take a quick image of something, I’ve placed myself so that the subject stands out; it’s well delineated. It’s not blending into the background. But it’s all very intuitive.

Walker: But with Warhol, it wasn’t just the experience of printing his photos that impacted you, right? It was an entrée to the art world.

Marcopoulos: Oh yeah. It plugged me in. Warhol’s painting assistant became one of my best friends. He and I would go see all these rap and hip-hop shows that started coming downtown. I knew I wanted to do something. I wanted to also make work. I just started taking pictures in the street, walking around. I started taking portraits of artists, because I had a certain amount of access. I photographed Andy. I photographed Richard Serra. You know, different artists from that time. Ashley Bickerton. And the way I photographed them is very casual. I was working Monday to Friday, nine to six, you know? Every day. But I found time to go take these pictures. At that time, you had people like Annie Leibovitz putting Whoopi Goldberg in a bath of milk and I was like, What the fuck? That’s the photography you would see in the magazines, so that’s how you start to think you have to shoot to make money, because for sure, I wasn’t going to make money in the art world with my prints on the wall.

But I could never do that. I would go meet Poor Righteous Teachers to take a picture, and I just took them just standing in the street somewhere. When I got the pictures back, I always thought, God, these are so boring. But now when I look at them, I think, Wow, these pictures are incredible because it’s just them and me, and we’re not trying to be anything other than that. I’m not lying on my knees. I’m not climbing on a ladder. My camera is up in my eye, and I click the shutter, and that’s it. And that’s the picture.

Courtesy the artist

Walker: You have a healthy bibliography of traditional, offset books, but obviously it doesn’t compare to zines. How do you think people know your work, primarily? Is there a singular way that people get to know the work? What place do the zines hold in getting your work out in the world?

Marcopoulos: The zines have been a huge aspect of getting it out into the world. The funny thing about zines is that when you make 150 zines with Nieves—Nieves might sell ten, five, eight copies to a bookstore in Berlin; a bookstore in Frankfurt, in Amsterdam, in London, in Tokyo, in Rio, in LA. So maybe five people in Berlin have this Nieves zine. But because there’s only five people that have it, they go to their friends and say, Check it out, I got this Ari Marcopoulos zine. And they go, Oh yeah. I think that’s how people have come to know me.

Walker: So are zines an integral aspect of your identity as a photographer?

Marcopoulos: Oh, yeah. I think they are, for sure.

Walker: I like that you’re making a distinction between the five people in Berlin who bought the zine, who are different than the five people who buy your book, don’t you think?

Marcopoulos: Yeah. Well, yeah, for sure. Because I think the zine is cheaper, one, and they’re also—

Walker: It’s more accessible, but at the same time, rarer.

Marcopoulos: Yeah. You have to be a bit more of a connoisseur, in a weird way. You’ve got to want to chase down all the zines; and you gotta be on top of it. You’ve got to have your finger on the pulse to know that it’s coming, and that you’re getting it.

Walker: So that appeals to you, in terms of the notion of the zine being more for the fans only.

Marcopoulos: The fact that it’s rarefied doesn’t really appeal to me. What appeals to me mostly is that the zine will find its way into the hands of somebody that will never buy a book. Maybe because it’s too expensive, or maybe because they’re really not into books.

But what happened, I think, through zines—and not just my own—is that some kids became book collectors. It’s like how the Printed Matter Art Book Fair has become like the hippest thing to go to for kids? I’m like, who are all these people? [laughs] I worked at the table at Roma Publications, because the publisher, Roger, is my friend, and people come up to the table, and they talk to you, and while they talk to you, they flip through a book, and they don’t even look up. It’s like a scene. It’s like a club. They have the whole zine section. When I go there, people come up to me and say, I want you to have my zine, my book, my records, my this, my that.

Walker: And that’s very nice in terms of the ethos of distribution, accessibility, and sharing.

Marcopoulos: A zine you can give away very easily. You make it, you give it.

This interview is an excerpt from Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (Aperture, 2023).