Portfolios

Charlie Engman Transforms the Internet’s Murk into Art

Engman’s experiments with AI offer an indelible collection of “cursed images” inspired by a feeling of being nostalgic for the present.

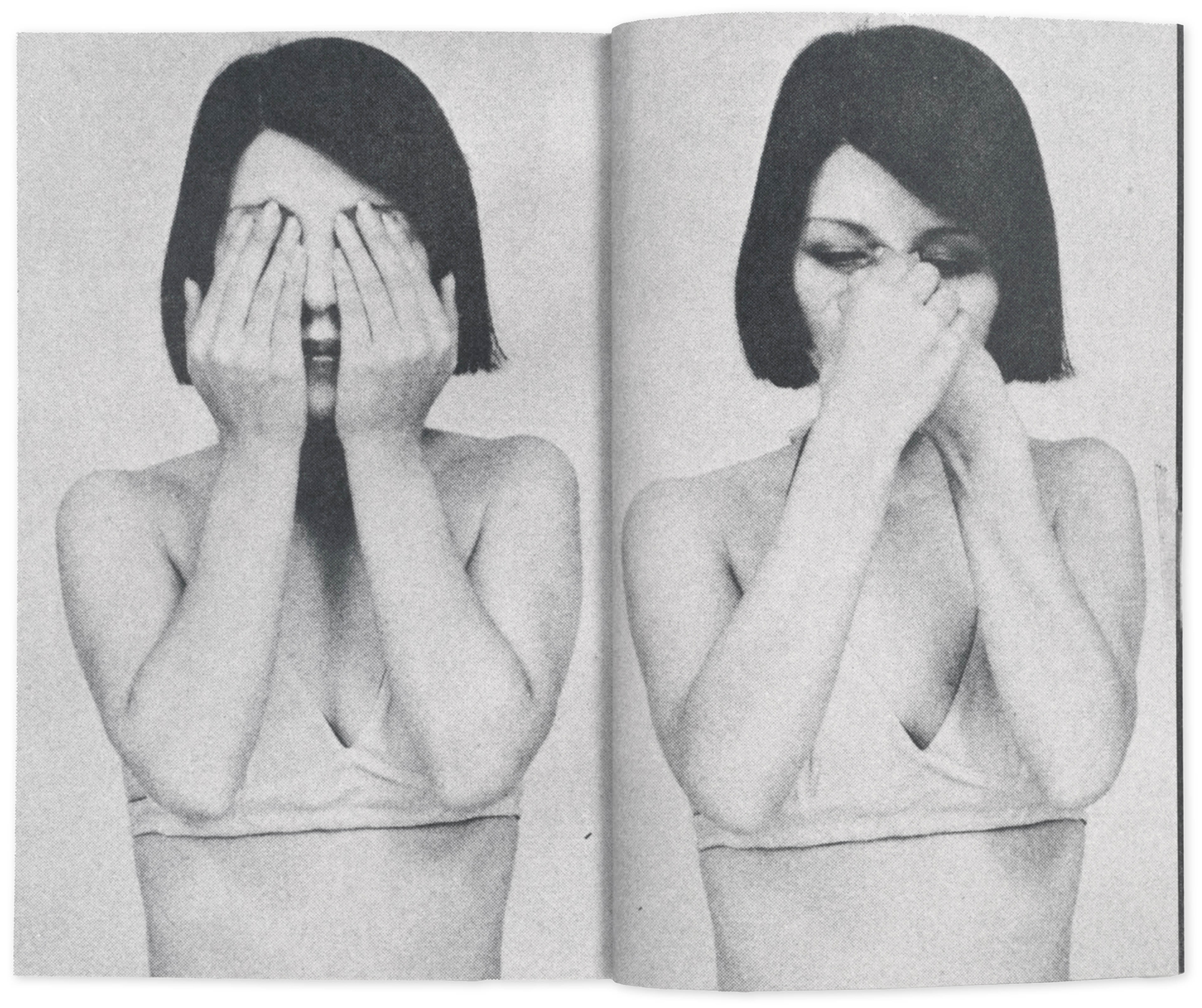

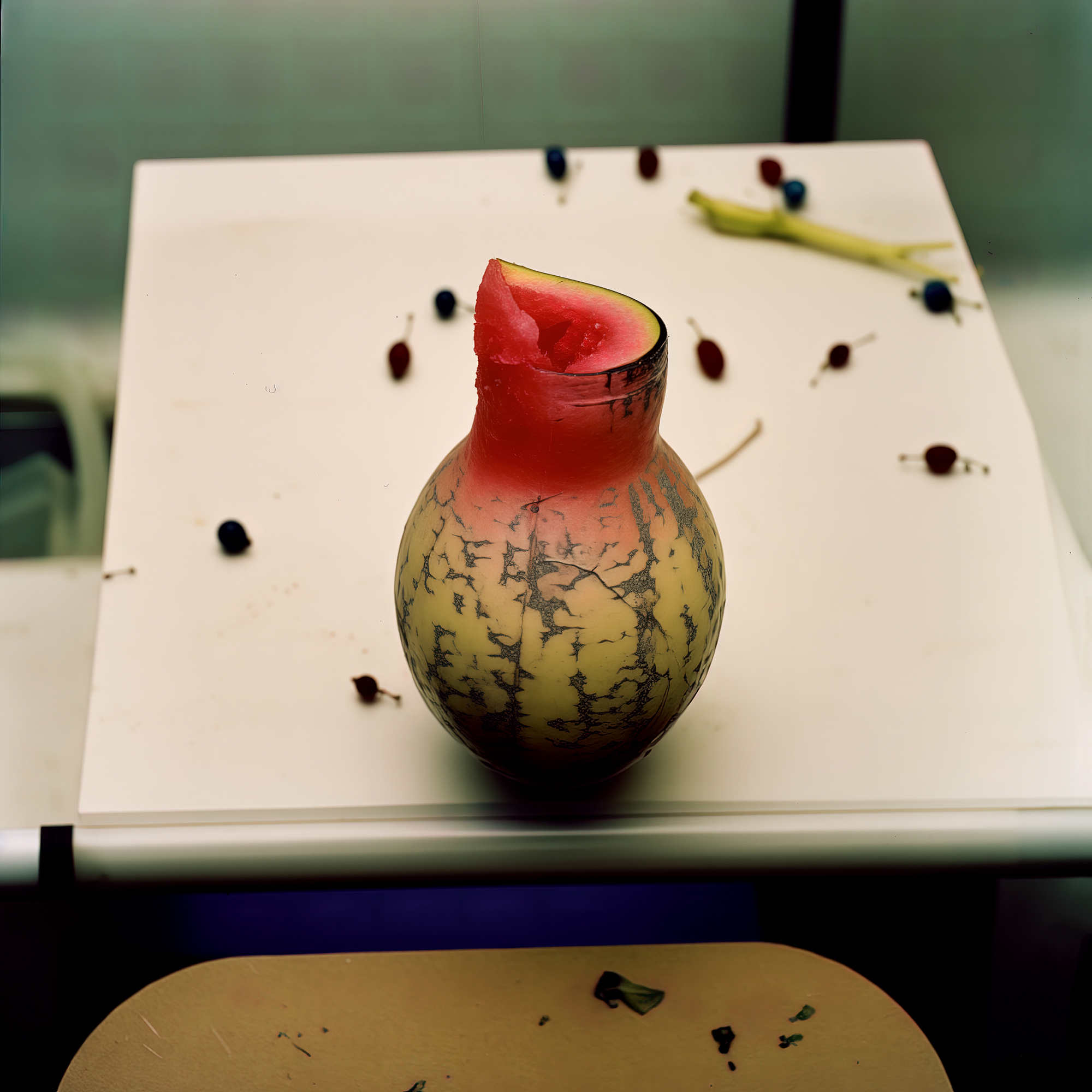

All photographs come from somewhere—are of something. At least that’s still the premise, even as AI-generated pictures suffuse the world. A cursed image, then, is one without context: someone slicing sausage with a bootleg Windows XP disc, a motorcycle tucked into a bed, so much wayward spaghetti. From nowhere, going nowhere; a scratch in the feed.

“They feel like products of the deep internet that have this authorless, golem-like quality,” Charlie Engman says of his recent work. “Images that have taken on a life of their own, that seem to have been created from the murk of the internet rather than by any one real scenario.” His new photobook is duly titled Cursed (2024).

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Engman is typically a camera-using, straight-ahead photographer, perhaps best known for a lengthy series of revealing, bare portraits of his photogenic mother. In the last two years, though, he’s become something of an AI whisperer, employing Midjourney, DALL·E, and their ilk of generative AI programs to dredge the internet. He plumbs the mushy, statistically average but practically unreal quality that makes AI-generated pictures derivative and bad until he finds something compelling: Body horror. Misbegotten hugs. Ceramic or part-human swans wading knee-deep in impossibly shallow parking lot puddles. Waxen human-approximates crumpled on bedcovers. The interface—where people touch objects and one another, where light touches an object—is the place in which AI miscarries.

Drawing on reservoirs of sleazy hard flash, incidental still lifes, and pickling Polaroids, Engman leans into these pictures being photographs, assembled from whatever clots of photographic data float through the internet’s sewer. “I feel like, weirdly, this work is the most photographic work that I’ve ever made,” he states. In his previous output, he was trying to push and bend photography’s conventions, its history. With the AI images, “I actually felt like I was running toward photography to see how close I could get,” he says, “and what that kind of closeness would mean in this new context.”

Are his pictures technically photographs? It’s hard to say, but their source images are, or, somewhere down the line, were. Engman’s pictures draw on a latent, ghostly indexicality, the sense that light touched something, a piece of something, bounced into a lens, and now the software is doing its best impression of that light.

The images in Cursed derive primarily from Midjourney, although a few incorporate Engman’s custom models or photographs he made. It was important to him to use accessible technology. In the spirit of the “cursed” genre—popularized on Tumblr in 2015 to describe certain lo-fi photographs with an unintentional creep factor—you don’t need special training (though maybe a taste for the uncanny) to pull the most haunted accidents. This sifting is part of Engman’s process. From a slough of trawled pictures, the software replies to each prompt with four composites. He’ll feed in his own images, add both language and image prompts, and process the pictures again and again until they eke that cursed look.

The square format, the nostalgic default of Instagram via the Polaroid instant camera, is also the standard for text-to-image models. Photobook aficionados, perhaps allergic to social media’s rigid conventions, “really balked at the fact that I was making a square book,” Engman tells me. The square is too basic, too accessible—which, he continued, illuminates a tacit line of critique of AI: that it is undermining the rarefied conventions of fine art (as well as scraping images without permission). The availability of cursed images is part of their threat: Simply by dipping into the mainline, you can find something that surpasses the most studied fine-art photograph for punchy strangeness.

Engman grants that there’s something a bit perverse to having made a photobook out of this material. A binding elevates and fixes the content it contains, marking a particular state of the art even as technology rushes on. It is all the more contrarian to pause images that might have had no destiny. Engman is standing in rushing waters. He described perusing images he’d generated not two years ago and finding them outdated, the quirks of early AI (extra fingers, mismatched eyes) already digested by pop culture.

“I became excited by this idea that you could be nostalgic for the present,” he says. “There’s an experience of things moving at such a scale that you couldn’t even be present with what you were making because you are already anticipating it becoming valueless or irrelevant.” The project, of course, also pokes at the notion that AI itself is a cursed invention, rushing to the world’s end. “Does interaction with the technology curse the user?” he muses. “Does it curse the author? Does it curse the viewer?” Engman’s recent pictures ooze from our AI-crazed moment but also float free of it. Consider yourself cursed.

All images courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257, “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”