Essays

Fashion Photography’s AI Reckoning

When a J.Crew campaign was revealed to be made with AI, fans of the brand felt betrayed. But the fashion industry has always had an elastic relationship with the truth.

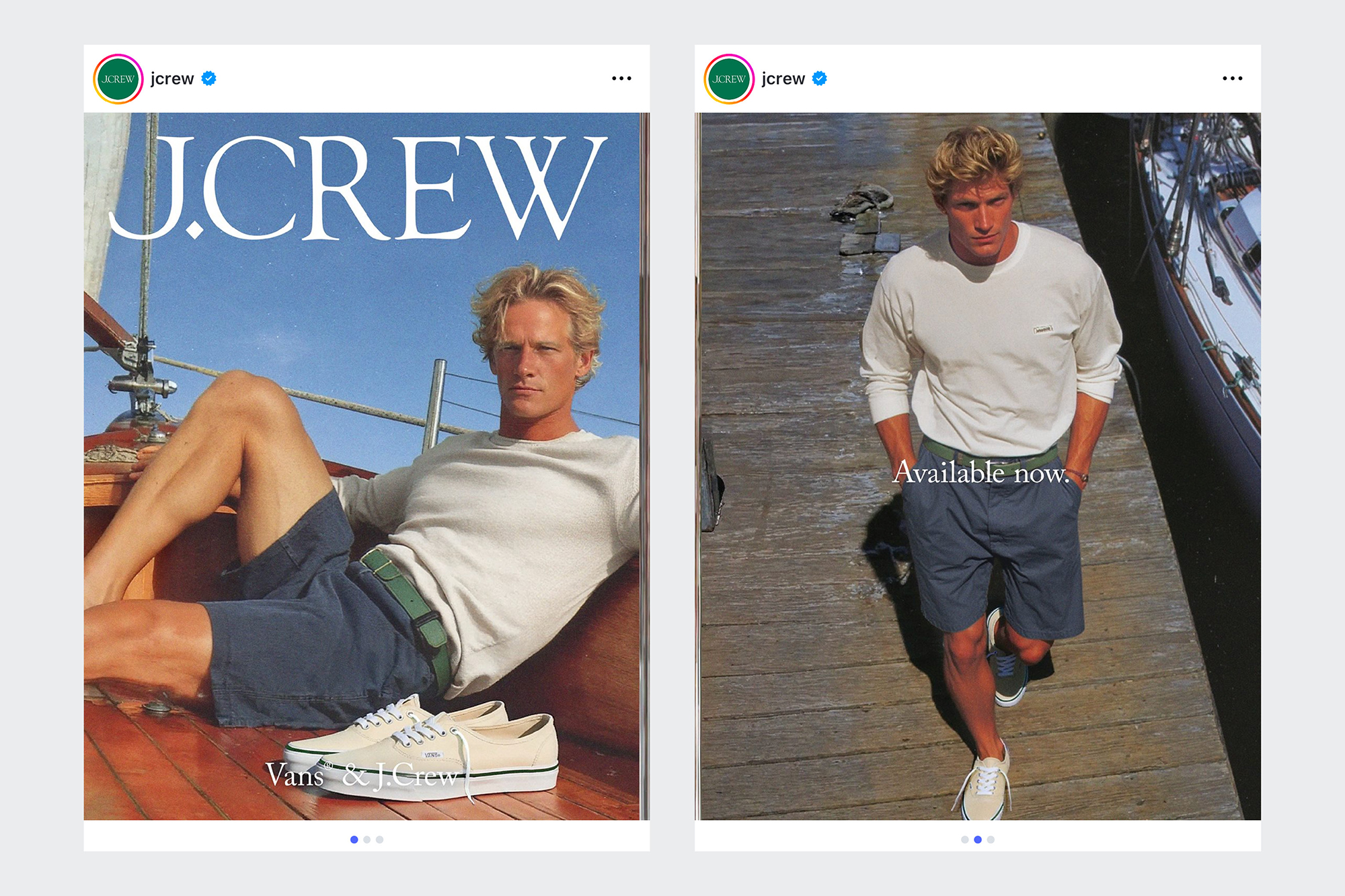

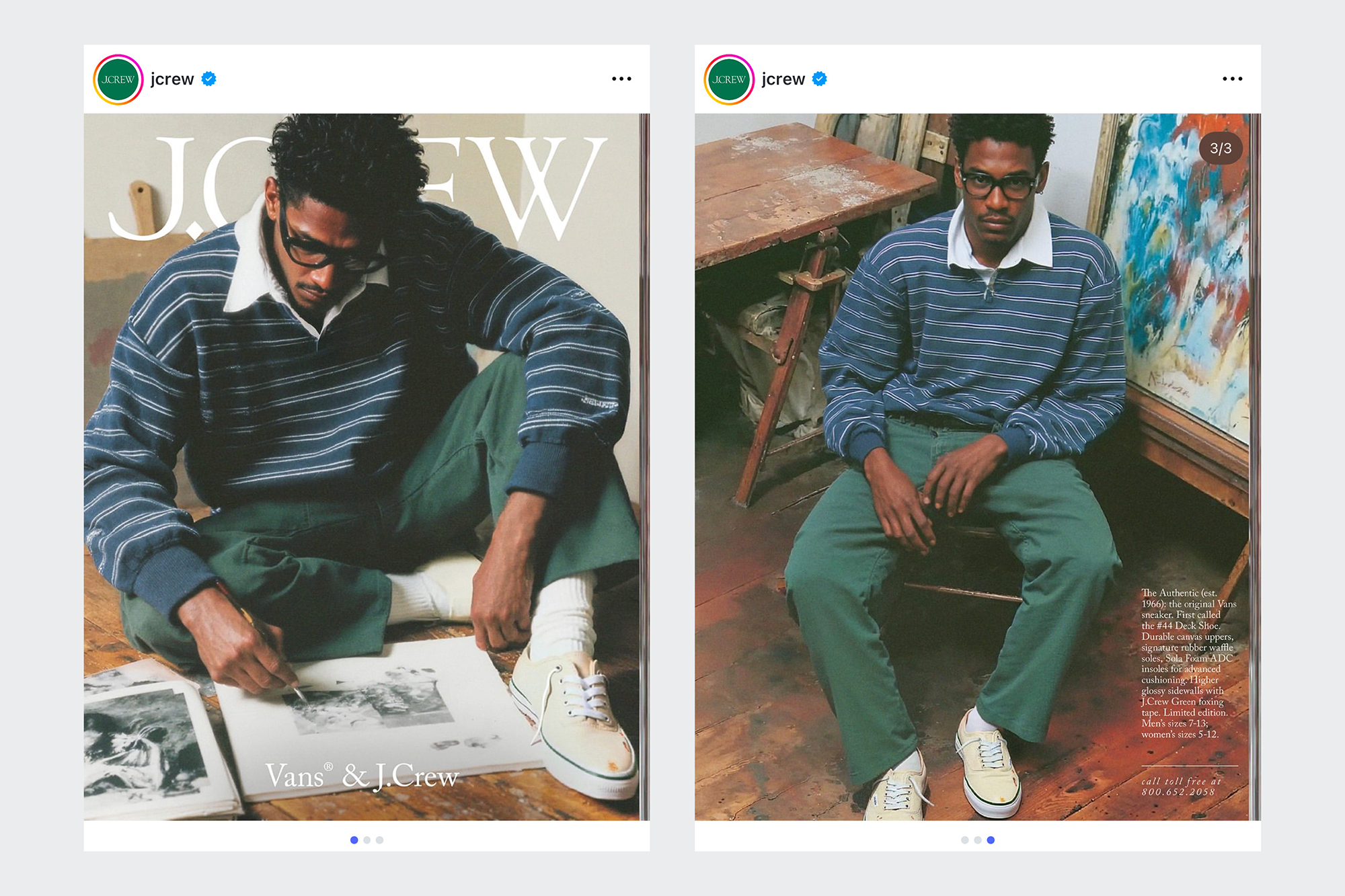

Last year, a J.Crew campaign promoting the company’s collaboration with Vans roiled certain corners of the internet concerned with the sanctity of menswear. The images seemed at home for a brand built on the signifiers of blue-blooded Americana: a barrel-chested WASP lolling on his daysailer, his flaxen hair swept back in perfect dishevelment, his jawline cutting perfect Harvard crew-team symmetries. Except there were some peculiarities. The contours of that jawline had dramatically realigned themselves in the time it took for him to dock. Other conspicuous glitches: the stripes of a rugby polo fuzzed into static, a foot implausibly torqued. The initially uncredited campaign was judged to be AI-generated. J.Crew eventually admitted it was the work of Sam Finn, a London-based AI image maker who, with presumably little irony, goes by “AI.S.A.M.”

To devotees of the mall brand’s “vintage” 1980s aesthetic (Ivy League, Nantucket, Caucasian) referenced by these images, the choice felt like a betrayal. Here was a brand cannibalizing its own history, sloppily regurgitating it and feeding it back to consumers like some malformed lunch meat. Worse, it was a machine making a mockery of their nostalgia. Their self-styled taste was revealed to be so flat as to be replicable by algorithm.

“I think the thing that mostly annoys people about AI is it’s sometimes really good and sometimes really bad,” Charlie Engman, a photographer whose engagement with AI straddles commercial and art practices, told me. “It fails a lot, and I think the failures are actually very instructive and tell you what we care about. And then when it succeeds people get upset because then they feel manipulated.”

The debacle was similar to one a month earlier involving a Guess ad in the August edition of Vogue, a two-page spread featuring a lissome model dressed in two looks from the brand’s summer collection. Here, too, there were inconsistencies: The model’s face subtly morphed across the images, her skin giving off the plasticized matte finish native to residents of the uncanny valley. This time, though, Guess wasn’t trying to fool anyone. In small print at the top of the page appeared the words “Produced by Seraphinne Vallora on AI.”

In both these cases, the images were realistic, that is, they spoke in the language of photography—naturalistic lighting, figures that credibly read as human. Objectors (there were plenty) noted the bitter irony of billion-dollar companies undercutting skilled labor to produce something that looked like what they normally do anyway. In fact, that was less ironic than the entire point.

The idea that advertising is unscrupulous is by now well understood. Fashion advertising in particular has a well-recorded history of emotional and technical deception. More than a decade ago, Photoshop caused an epistemological crisis—suddenly the waistlines of models in advertising and consumer magazines shrank to unnatural degrees, and cheek fat dissolved with the swipe of a cursor, leaving so much body dysmorphia in the wake of the healing brush tool. Even celebrities—the already beautiful—were not immune to the retoucher’s gaze. The boundaries of visual reality were compromised. The public learned that photographs could now lie, and probably were lying.

Courtesy Whitney Museum of Art and Scala/Art Resource, NY

The fashion image’s elastic relationship with truth stretches further back than the advent of Adobe software. Artifice was part of the deal from the beginning. Edward Steichen, the godfather of commercial fashion photography, introduced tricks of lighting, focus, and long exposure to manipulate the texture of fabric or flatter a face. As technology has become more sophisticated in pursuit of the same goal, AI’s total artificiality is, in many ways, more honest. Andrea Petrescu, the twenty-five-year-old cofounder of Seraphinne Vallora—the marketing agency behind the Guess ad—articulated, perhaps inadvertently, a philosophical loophole. “We don’t create unattainable looks,” she told the BBC. “Ultimately, all adverts are created to look perfect and usually have supermodels in, so what we are doing is no different.” The fashion industry, long maligned for promoting unattainable standards of beauty, would seem to reach its logical endpoint in AI: a standard of beauty that cannot be accused of being unattainable, because the beautiful people don’t exist.

The idea that advertising is unscrupulous is by now well understood. Fashion advertising in particular has a well-recorded history of emotional and technical deception.

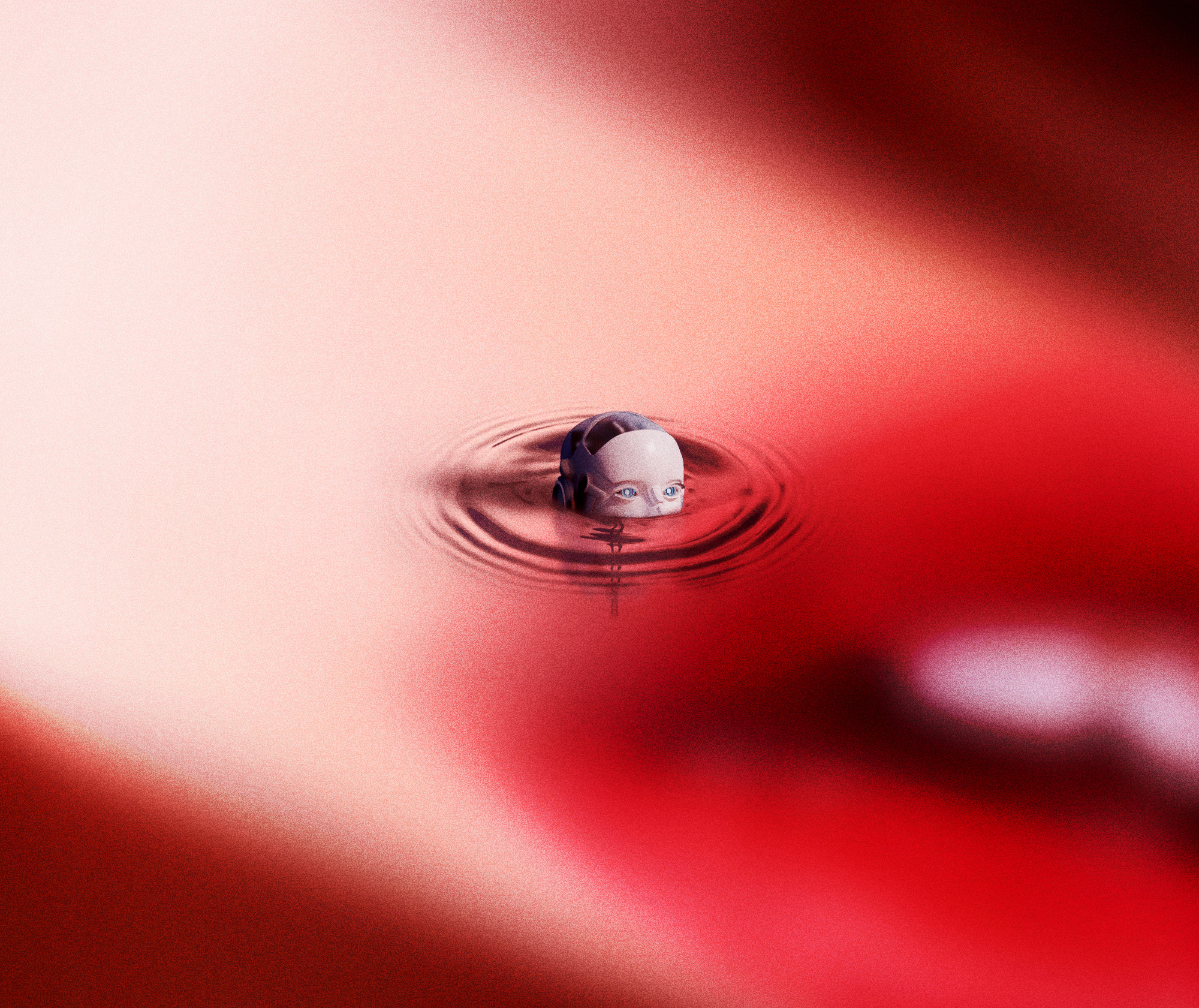

From a world-historical view, AI is simply the latest entry in industrialized automation. The increasing accessibility of AI tools means what once took dozens of specialized roles can now be achieved (or approximated) by one person clicking around in Midjourney. Some of the most conspicuous uses of AI in advertising have been commissioned by multimillion-dollar companies, which by their nature must adhere to capital’s ruthless logic. Finn, for instance, is credited with AI imagery for mass-market apparel brands like Ugg and Skims that is, like his J.Crew work, relatively tame compared to the nightmarish stuff he’s cooked up for Alexander McQueen (gargantuan beetles) and Gucci (a psilocybin-soaked AI sequence shoehorned into last year’s The Tiger, a bizarre fever-dream-as-brand-showcase directed by Spike Jonze and Halina Reijn and starring Demi Moore). For brands that wish to telegraph an edgy persona, AI reads like shorthand, if not compulsory.

Laura Dawes, a director at the London office of Webber Represents, a creative agency that manages photographers as well as stylists, set designers, and art directors, told me that navigating demand for AI is an evolution of what she’s always done as an agent, which is to manage expectations. “The thing about artists is that everyone is so unique,” she said. “I’ve had some really embrace it, and that’s usually in a controlled studio setting, something that’s more, say, constructed. But then in an uncontrolled environment, with natural light, that can be quite hazardous.” Dawes said she has seen clients use AI to build mockups for campaigns, which invites an intolerable level of risk: “You’re making an artificial image and using that as a guide and selling that to stakeholders on set when it’s not physically possible.”

Commercial adopters of AI are seduced less by the technology’s supposed mystique than by its labor efficiencies. It’s a short leap from fast fashion’s already algorithmic enterprise to AI’s promise of cost optimization. A recent report from the International Advertising Bureau projects that generative-AI creative will reach 40 percent of all ads beginning this year, confirming what anyone who watches YouTube videos or regularly rides the subway could already predict. It’s easy to see why AI would appeal to J.Crew, a company that filed for bankruptcy in 2020 and seems to be working through a prolonged identity crisis. “In a way, you can’t fault companies like Guess or J.Crew for doing this, because it’s just following profit models that have always existed,” Engman said. “Having worked in a lot of these jobs, you know, the creativity is very marginal. From a conceptual standpoint, it’s like, yeah, sure, make the J.Crew catalog.”

“Like it or not, this technology is here,” said Kalpesh Lathigra, who teaches in the MA commercial-photography course at London College of Communication. Lathigra, an artist and documentary photographer who also works commercially, believes that the industry will see what AI can do, but more importantly, what it cannot. “Personally, I’m not interested in AI. I would much rather get out into the world. A machine can give you millions of possibilities, but it can’t give you that elusive, intangible thing that draws us in and holds us, which has remained the same since the dawn of photography.”

Photographers and models, the image-industry jobs with the largest cults of personality, may be at less risk than less visible technical roles. “The people that I’m most worried about are the set designers,” Engman told me. “That’s the job that I feel is already disappearing.” Those roles are being supplanted by the elevated presence of retouchers, some of whom have cannily rebranded themselves into what Engman refers to as AI consultants, “which is a very interesting thing, because historically, retouchers were not seen as a particularly creative part of the process.”

There’s general resignation to the idea that AI is hastening entropy in a certain part of the medium. “The race to the bottom I feel will only apply to the basics of image-making—what was once referred to as ‘pack photography,’ home catalogs, basically, but today is product imagery for e-commerce,” Lathigra told me.

Dawes agrees. “When friends of mine were entering the industry, there were a lot of entry-level gigs mainly based around e-commerce, where people could do those kinds of jobs and have the ability to shoot their personal work on the side,” she said. That was only a decade ago. “Now there are brands producing all of their e-com in AI. That for me is quite scary, because that’s such a large section of the industry.” Dawes said she now routinely deals with clients whose entire catalog of product photography is AI-generated.

Engman, who has shot for Prada and Gucci, was an early AI adopter, starting to play around with AI models in 2022. He has an openness toward its possibilities that other photographers might not. It’s an openness that has made him sought-after in the fashion world as an AI oracle; he seems to talk about AI as much as he uses it. A couple of years ago, he estimated that 80 percent of his work engaged AI in some way, like a campaign for Acne that featured statues of vaguely humanoid figures who had seemed to ossify into seashells while shopping. He puts his current AI output vis-à-vis commissions much lower. Did he get bored, or is the flawlessly formed surface of AI’s bubble already deflating?

“I felt like I was participating in the bubble a few years ago, and now I think we’re in the awkward growing pains of moving out of the bubble,” he told me. Engman recalled a recent shoot with Coach, which had commissioned him based on his AI work but then realized that wasn’t actually what it was interested in. “What they wanted to do was much easier and more effective to do in CGI,” he said.

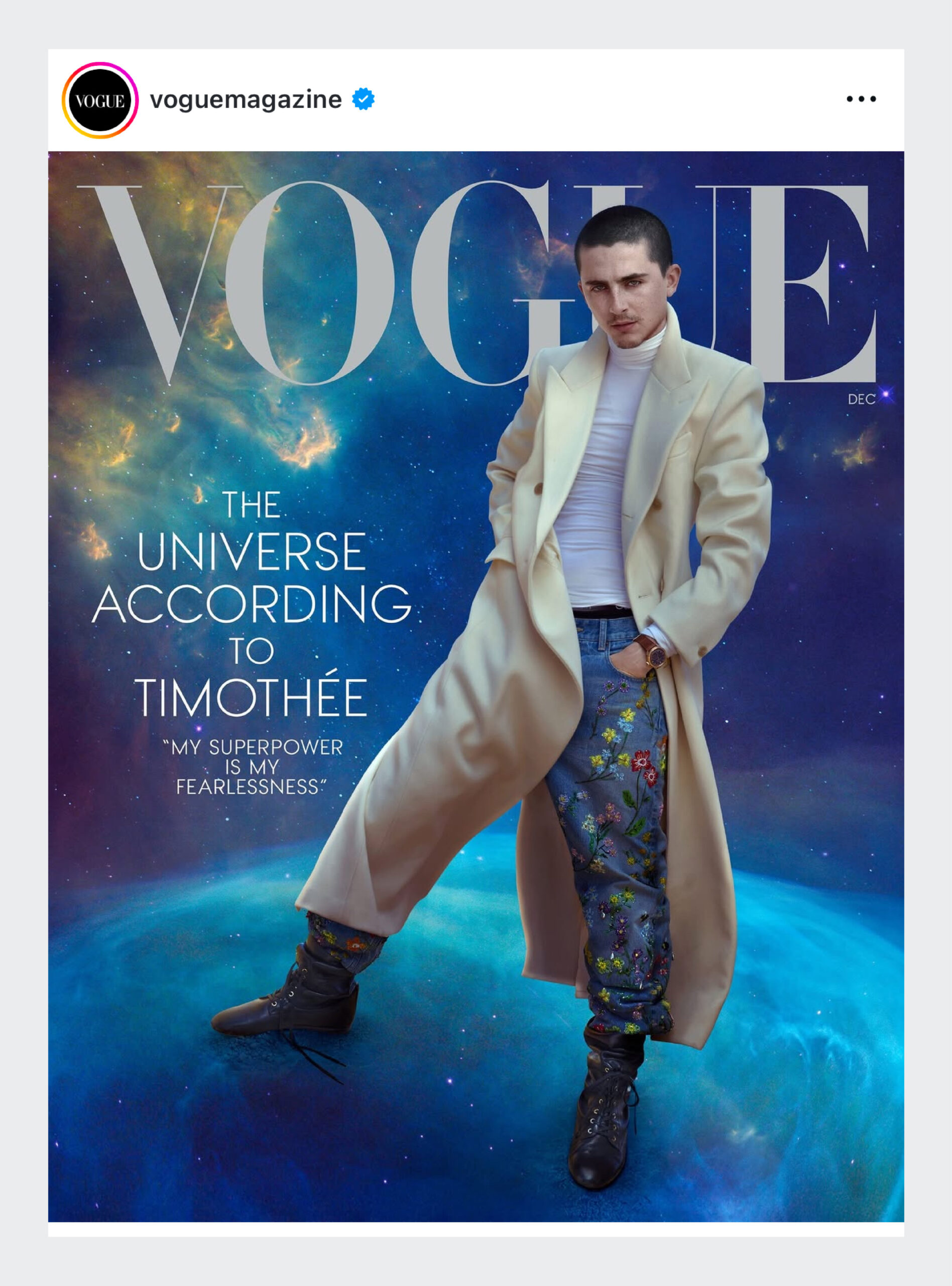

The taste of AI has already coated our mouths enough that it may not matter if it’s actually present at all. Vogue’s December 2025 cover features an image of the actor Timothée Chalamet dressed in Celine jeans, cream topcoat, and untied motorcycle boots, inexplicably posed on top of a swirling nebula. It calls to mind the kitschy roll-down backdrops of school picture day. The portrait, shot by the perennial Vogue contributor Annie Leibovitz, is not AI, but with its disproportionate scaling and goofy premise, has the same acrid aftertaste. In many ways, that’s worse. If we’ve reached the point where humans are aping machines aping humans, especially unconsciously, we’re further down the valley than we realize.