Photobooks

How Can Photobooks Expand the Canon?

The team behind a British publisher speaks about the bookmaking process—and how a sequence of photographs can create an emotional experience.

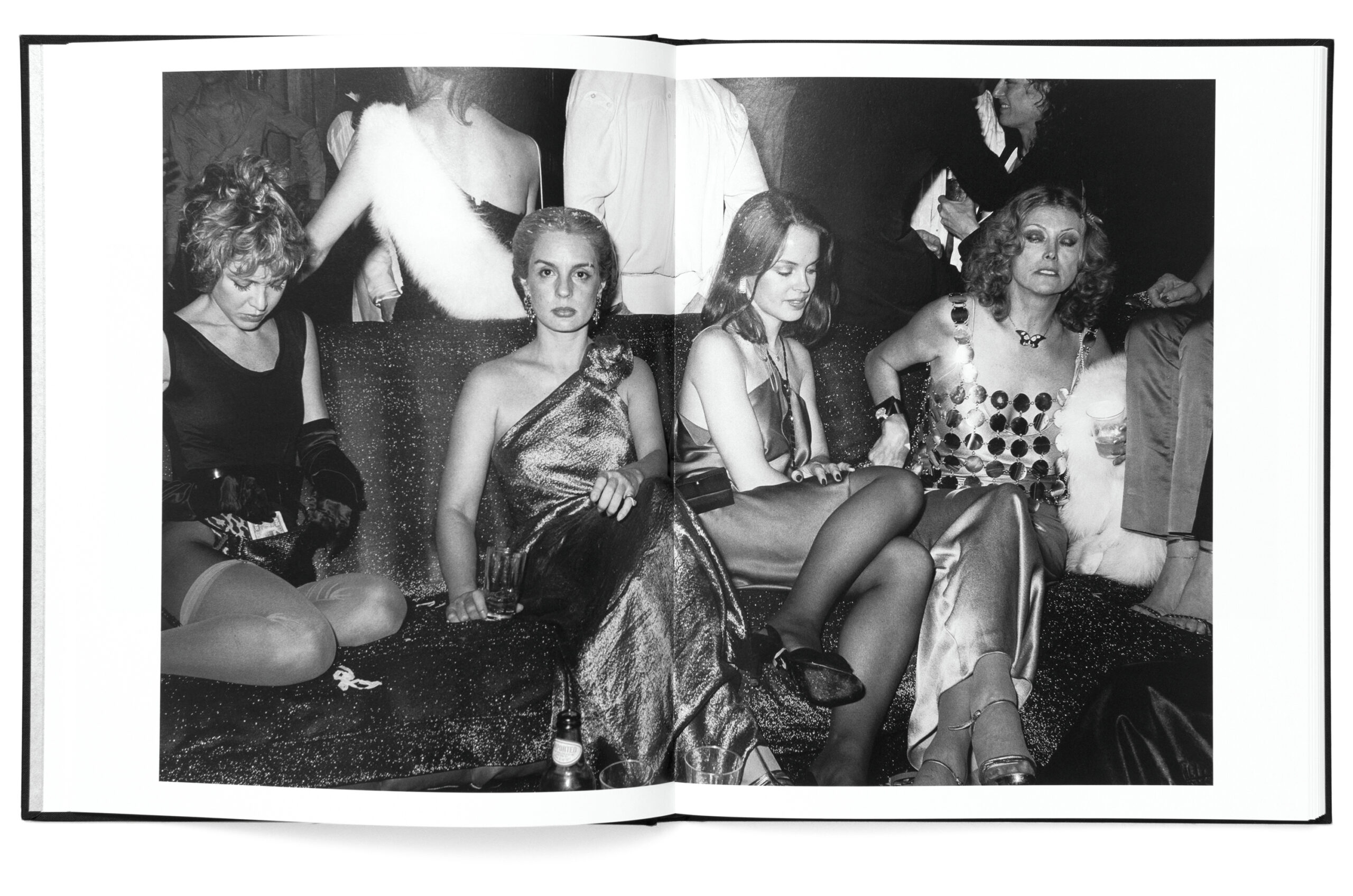

Gregory and Rachel Barker founded their photobook publishing house, Stanley/Barker, based in Shropshire in the West Midlands of England, in 2014. Their first publication, Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 (2014), sequenced the photographer’s unpublished portfolio as a one-night journey into the depths of perhaps the most mythical nightclub ever. Stanley and Barker, who studied photography and art in London, and who are now both in their midthirties, have since published monographs by lesser-known but nonetheless formidable photographers, reviving interest in Mimi Plumb, Judith Black, and Jack Lueders-Booth. Superb black-and-white reproductions and narrative structure have become hallmarks of the Stanley/Barker approach, as well as a sensitivity to the look and feel of a publication held in the hand.

Alistair: First off, could you tell me how you both got into publishing?

Rachel Barker: Greg studied photography, and I studied fine art. Then we met at Blurb, the print-on-demand book company.

Gregory Barker: It was quite fortuitous. We had both graduated and gone to work at probably the worst place to work when you’re interested in publishing. But it was 2009, the very start of the golden age of photobooks. We ran a book fair together called Photo Book London, which was the first photobook event in London. But we did it only once. Then, we spent the next three years looking for our first project, because we had a very clear idea of what we thought a photobook could be.

In 2013, we went to Paris Photo and saw Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 images as a wall at Galerie Thomas Zander, and then we spent the next six months convincing Tod and Thomas to let two twenty-five-year-olds who had no prior experience publish a book about it.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Alistair: And now, a decade later, following the pandemic and other changes, how would you describe the photobook market in 2023?

Gregory: It’s returning.

Rachel: It can change rapidly, and we keep our eye on it constantly. With the decisions we make and the books we choose to publish, we have to be sure that in the current market there is an audience for a book and that we are going to be able to sell it. We’re just gearing up for the spring 2023 release of Trent Parke’s new book, Monument, and it’s one of our biggest presellers ever. People are really excited about it. So, that’s a signifier that there is still a real energy around photography and photobooks and buying them and printing them.

Gregory: We’ve always seen our role in the publishing community as righting the wrongs of our forebears in terms of finding these projects that should have been books, but they didn’t quite get the attention they deserved. We’ve always thought that we need to make books that people actually want to buy and are important books that need to exist.

Alistair: So as much as they are reassessments, they are also contributions to the canon?

Gregory: Yes, finding where those holes are that shouldn’t exist. We do a lot of work with people who were in Massachusetts and the surrounding states in the 1970s, such as Sage Sohier, Mark Steinmetz, Sergio Purtell, Susan Kandel, Paul McDonough, Mike Smith, Joan Albert, Henry Horenstein, Jack Lueders-Booth, and Katherine Turczan. There was such a movement of female artists making incredible images. And for some reason, it didn’t quite take off at that time. It’s really bizarre. We’ve been quite fortunate to be able, as you say, to reassess the canon and put that important moment back in place.

Alistair: How do you conceive a photobook?

Gregory: For us, the bookmaking process is always about being as collaborative as possible. It’s definitely a three-way collaboration between the artist, us, and the designer. We’re always trying to take the artist’s work and present it in a way that allows the viewer to have the greatest depth of understanding. We don’t want the book to be our taste. We want it to be an extension of the content.

Photographers spent so long making these bodies of photographs—they devoted twenty to thirty years of their lives. So, it’s important that the physical object have as much attention to craft and design as possible. But having said that, we keep the insides of our books very simple. Once you get past the title page, what follows are clear, beautifully rendered prints of the photographer’s work, because at that point, we’re in their headspace. Everything coming before is trying to put the reader in the space where they can appreciate the photographs to the best, fullest extent.

Alistair: You mentioned that you’re very motivated by the principle of narrative.

Rachel: Yeah. Probably the book that really inspired what we do was Watabe Yukichi’s A Criminal Investigation from 2011. When we both looked through it, we were just so blown away—it is so elegant and simply done. But the detail in it is just amazing, in terms of the points at which it makes you think about the journey you’re going on, and the references, such as the typewriter font and the band around it, make the book feel like a criminal dossier.

Gregory: The sequencing.

Rachel: The sequencing, yes. You’re following this sort of investigation. It’s a story. It’s like a novel but visual.

We took a lot from that book and put those ideas into our publications. Looking at the Mark Steinmetz books that we publish; Carnival (2019) follows a day at the carnival. When you’re looking through its sequence, we take you right from the start, arriving at the carnival, through enjoying the carnival, to the end, when the daylight fades, and the lights of the carnival come on. It’s really simple, but it’s a pleasurable experience, hopefully, for whoever buys the book and looks through it. They’re taken on that journey.

Gregory: There’s nothing more boring than “this looks like that.” In sequencing, people so often think, Oh, there’s a picture of a ball. And then on the next page, There’s a picture of a moon. That really takes you out of experiencing the pictures. Instead, it puts you into a space of trying to find how someone has linked things visually. Whereas we’re always trying to get back to—no one talks about it in reviews or anything anymore—the emotional experience of looking through a body of work. We’re trying to get people away from looking at pictures and toward experiencing looking at pictures. If we can give them something very direct, like a journey that they’re going to go on, once the brain cops on to this very simple idea, you’re no longer looking at the sequence. You’re experiencing the pictures and the flow of pictures. That’s not to say we don’t do conceptual editing. We’ve just edited a Mimi Plumb book, and it’s sequenced to the Zen story of the ten ox-herding pictures, like the journey to enlightenment. It was a really interesting way for us to edit a book.

Alistair: Journey is a really good word to describe it, because it’s almost as if the journey you take the reader on is slightly different from, perhaps, the journey that the photographer’s portfolio established. Do you think that’s a fair distinction?

Rachel: Yeah, I guess. Sometimes the photographer trusts us with their work, and the sequence we put together perhaps isn’t what they brought to us in the first place. I mean, even looking at Studio 54, I’m not sure Tod Papageorge ever thought about those images in that sequence—of coming to the nightclub, and then in the middle of the book, you’ve got the buildup to the real crescendo of the party in full swing, and then you see, as it kind of peters out in the last pages, people lying around on the floor, they’ve had too much to drink, they’re too tired, and then it ends.

Gregory: He didn’t have the idea, but he did do forty PDFs of the sequence. We were incredibly fortunate that with the early photographers we published—Tod Papageorge, Bill Henson, Larry Fink, Karen Knorr—it’s like having a master class every time you work with one of these people.

Alistair: Why do you think sequencing is not up for discussion in the critique of photobooks? What do you think the critique is more attentive to?

Gregory: I think it’s because it’s harder to talk about your emotional response to art. It’s a really difficult thing to do well in any way that means anything to anyone else. Ten people can look at a book and have ten different emotional responses.

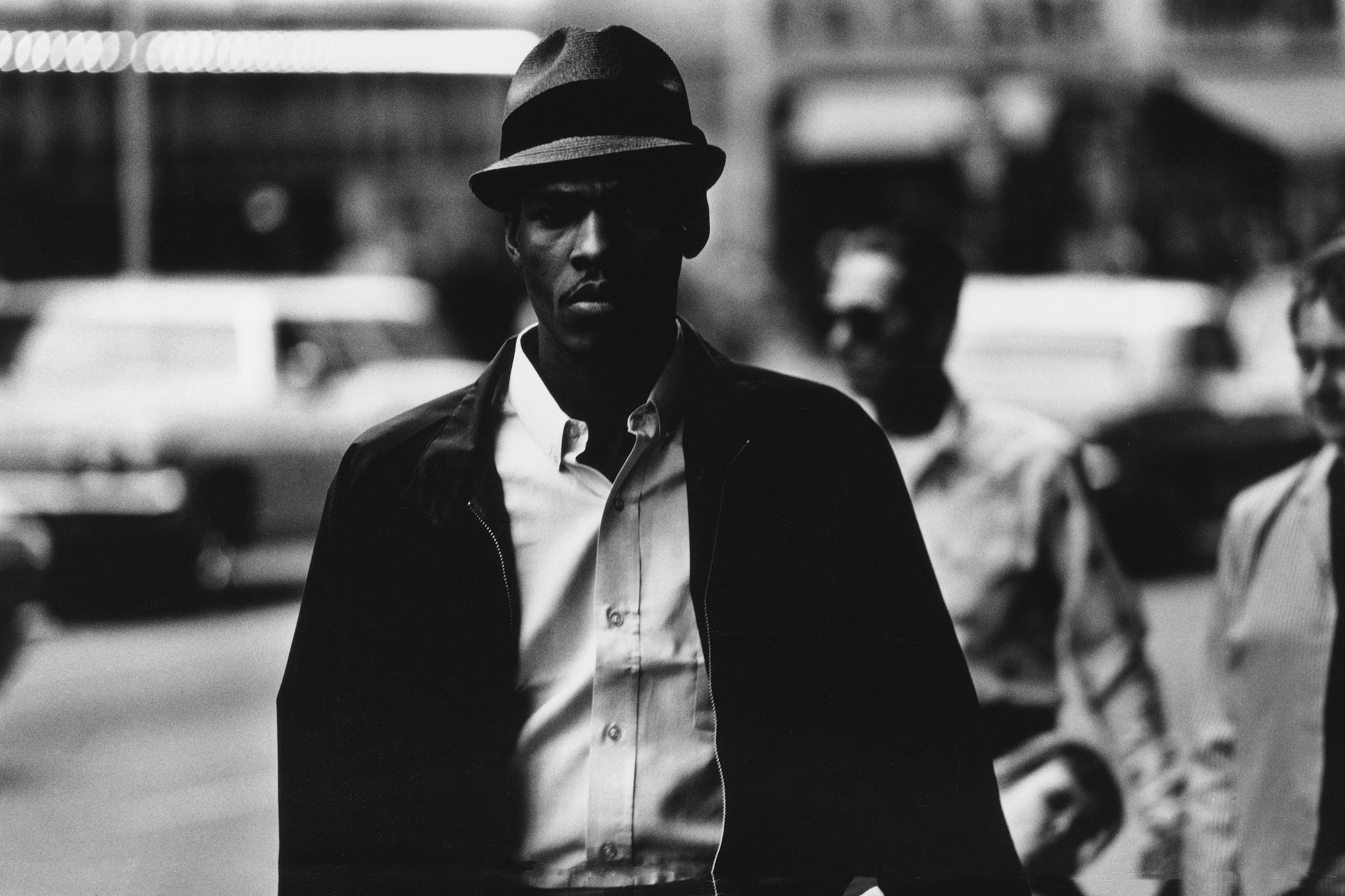

Dave Heath’s work—we’ve published two of his books, One Brief Moment (2022) and Washington Square (2016)—is people walking along a street, and there’s nothing inherently emotionally driven about a street scene. But the way he captures skin and light has such an emotional resonance; it’s almost impossible to say how that works. It’s like the Minor White quote about looking at photographs to see what else they are, which is difficult and kind of nonsensical at the same time. But that’s what’s special about it. We always look for books that are two things. So, to one extent, Dave Heath’s books show street scenes; someone who’s not interested in photography can totally understand these are pictures on the East Coast in 1967. But someone who’s interested in our world can look at them and see unfathomable depths of beauty and sadness.

All photographs courtesy Stanley/Barker

Alistair: It’s also about a kind of metropolitan life, a kind of interaction with other human beings that doesn’t really exist anymore. It’s gone. Washington Square is not like that anymore. As we see in some of these portfolios, there is a sense of loss articulated in the act of looking back and trying to reappraise the canon.

One last question. You’ve got a lot of books piled behind you, and I don’t think they’re all published by you. So, you enjoy collecting books yourself, I presume? How do you buy books today?

Gregory: More often than not, the books we buy now are bad books of good photography. Because the type of photography that we love generally wasn’t made into beautiful books, since it’s from an earlier time period. We tend to buy a lot, just because you see one picture by someone, maybe scrolling through a museum’s archive pages, and you think, I bet there’s more there, there’s got to be more, there’s a whole series there. So you buy the book to see, and then you realize there is just that one picture. But then, you’ve got the book.

Rachel: We come back with a lot of books from events as well. We’ll always go in and have a look at other book stands and end up buying more than we need.

Gregory: Yeah, and the bookshelves fill up, and then other rooms get filled with books.

Alistair: It’s a terrible problem of modern life. It’s not the bookcases you have, it’s the book towers at the side of them.

Gregory: If a fire marshal came in, they’d just say, “Oh, what are you doing? There’s kindling everywhere.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra,” in The PhotoBook Review.