Portfolios

How Can Synthetic Images Render Blackness?

When the artist Minne Atairu began using AI to make glossy, Afrofuturist images, she discovered a dataset biased toward white women, unveiling the myth of the neutral algorithm.

In today’s humanities classrooms, the gravest anxiety stems not from the relentless corporatization of universities, or even the end of the English major, but rather from students’ nefarious use of artificial intelligence. The kids are liars, cheaters, and dumber than ever, my professorial colleagues shout, if not in so many words. AI is often polarizing: all good or all bad. In everyday life, though, many of us use AI without even knowing it: navigation, fraud-detection services, social media feeds.

To demonstrate Silicon Valley’s ironclad control over these technologies, many artists have been using AI to disrupt this kind of Manichaean thinking, looking deeply into the mirror that algorithmic hegemony holds up to our unequal society. The New York–based artist and researcher Minne Atairu came to her AI work in 2020 while studying art education, generative AI, and policy in a PhD program at Columbia University’s Teachers College. “I became interested in AI in the classroom, specifically how we can address the needs of Black students, because we learn in spaces that are very distinct,” she tells me.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

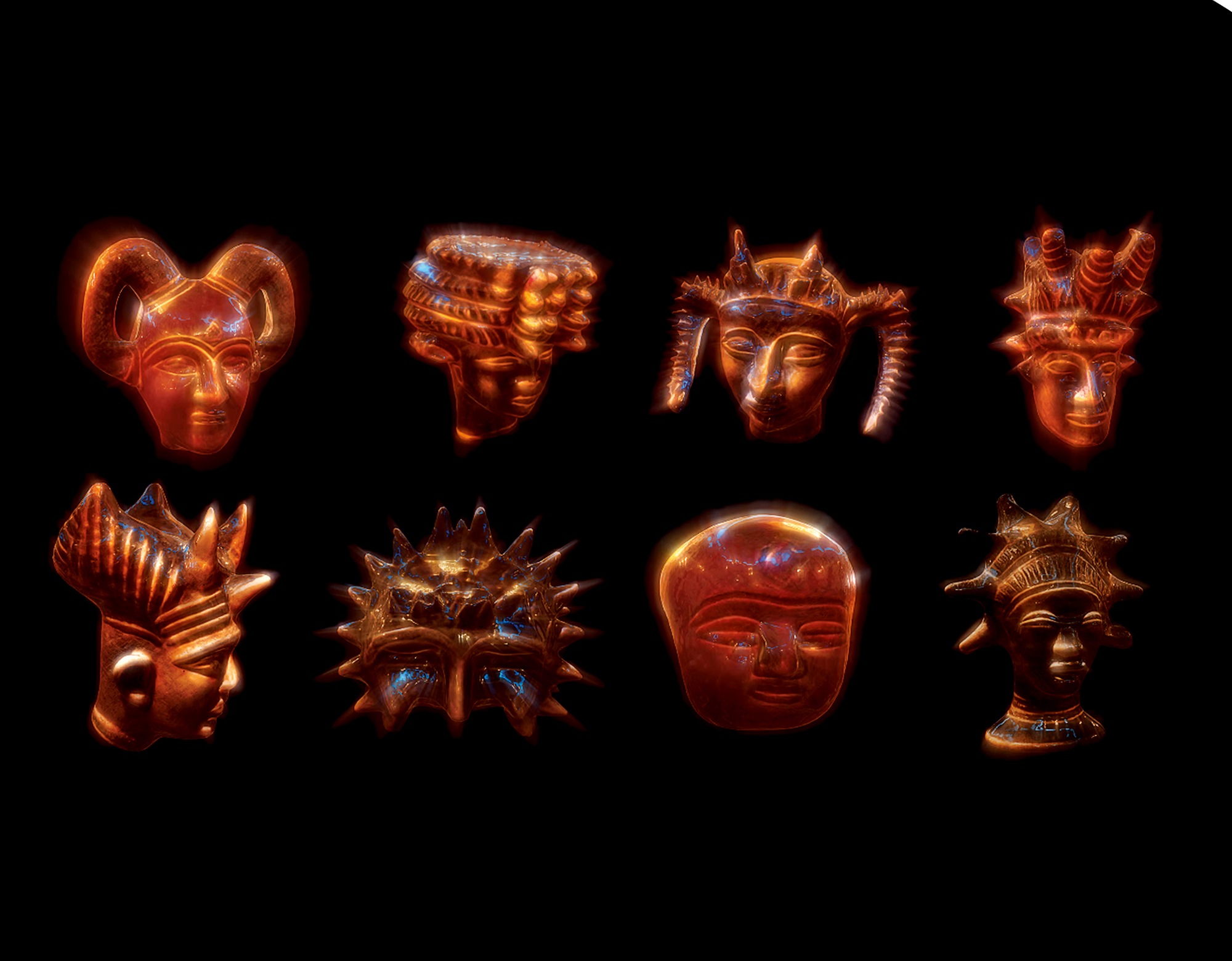

What goes by simply “AI” is, in fact, a broad spectrum of different and diverging programs, developers, materials, datasets, frameworks, and processes. Over the years, Atairu has explored a few, including an early machine learning framework called a generative adversarial network (GAN); StyleGAN2; text-to-image, text-to-3D, and text-to-video models; DALL·E 2; augmented reality; and various other flavors of machine learning. Beginning in 2020 with her Igùn series, she’s consistently scrutinized and scrambled the assumptive logic of computer vision while drawing attention to the silences and absences in Black archives.

These days, Atairu uses mostly Midjourney, a generative AI program created in 2022 that produces images based on text prompts. Recently, she began making Cornrow Studies (2024)—close-up portraits of dark-skinned Black women wearing blue and pink sculptural cornrows. Some of the pictures are so tightly framed that certain facial features are cropped out—lips, eyes, chins, foreheads. A closer look reveals that something is askew. The hair sits a little too deep on the forehead. Or the cornrows rest atop the head instead of being braided into hair strands. In one image, a Black woman has a shaved head with sea-blue braids swirling atop it, like an atomic wig or glued-on hairpiece. Bulbous sweat drips from a forehead, counterposed with tears dried on the face, tears that have funky turquoise residue. Such secretions, rather than humanizing the models, only nudge us further into the uncanny valley.

For all its allure, Atairu’s art resists the temptations of the technocapitalist aura.

Atairu’s unheimlich headshots suggest how Midjourney as a technology understands itself and its capabilities. “What I’ve tried to do as a researcher is use Midjourney as a tool to investigate the ways in which developers have paid attention to Blackness, particularly as it relates to hair and the ways that Black people present themselves,” Atairu explains. “That’s sometimes inconsistent with what the algorithm has been trained on in terms of the dataset but also how the developers themselves are thinking about Black representation in their tools.” (Many generative AI systems are trained on not simply normative images but on uncompensated labor.)

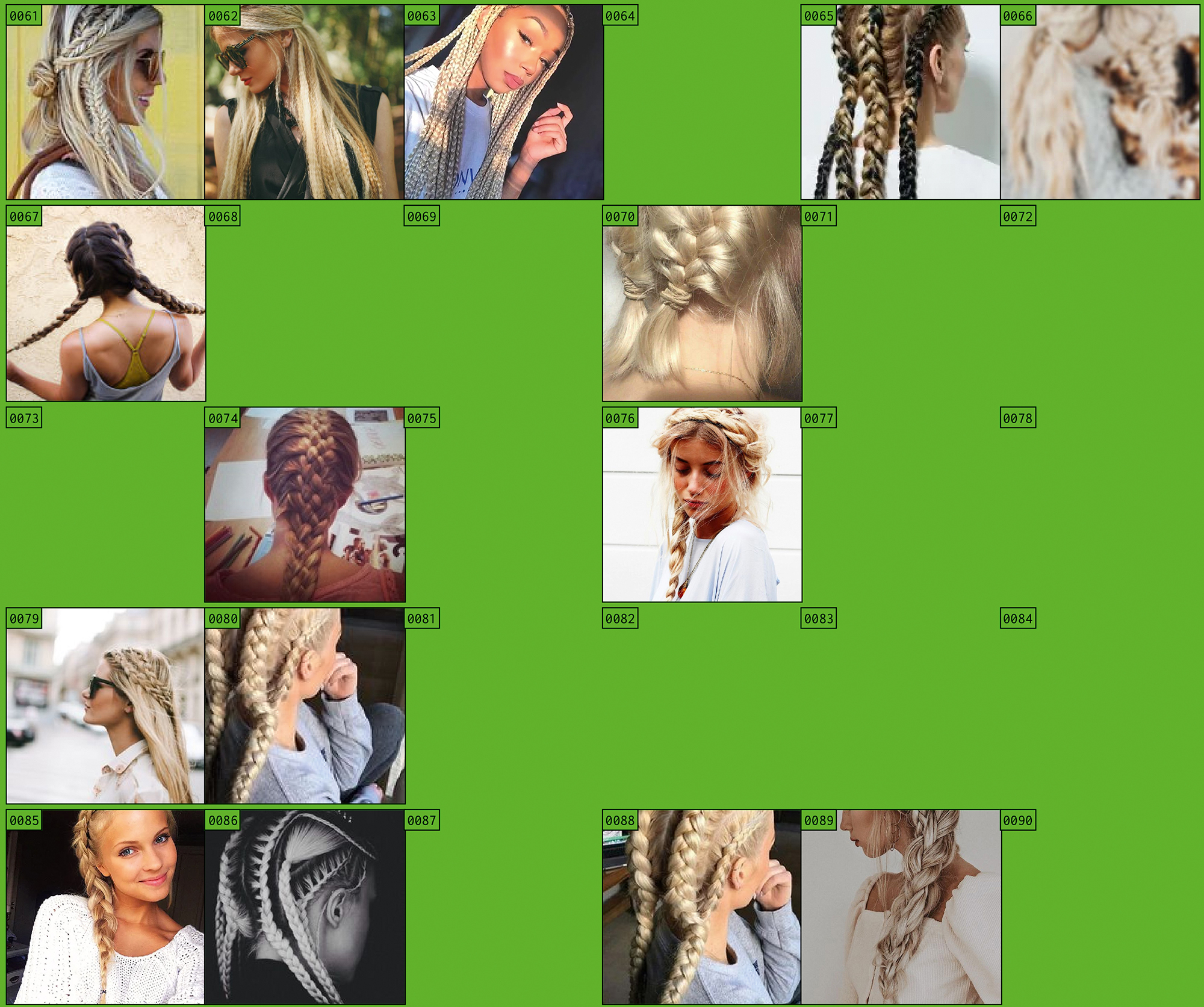

Hair and skin color—both intense signifiers of racialization—serve as leitmotifs in Atairu’s body of AI-generated portraiture, beginning with S-T-R-E-T-C-H Wigs (2021), which portrays a glitchy face and shape-shifting orbicular wig. The ongoing Blondes Braid Study started in 2023 with the following question: Can Midjourney (V4) accurately generate studio portraits of twins with “blue-black” or “plum-black” complexions and blond braids?

The algorithm did not provide. The Midjourney outputs had neither blue-black skin nor braids but mostly light-brown complexions and wavy, chemically straightened hair. When the artist conducted a search for “Blonde Box Braids” and “Blonde Braids” within LAION-5B—the open-source dataset of five billion internet-scraped images that Midjourney is trained on—she found that the index overrepresented caramel-complexioned Black women and white women. On the one hand, Atairu’s ongoing braids series examines the distinction between the description and the image, calling attention to the anti-Blackness, racism, and bias in generative systems. On the other, it sheds light on phenotypical obsessions, a white-supremacist insistence that we can see race.

A number of Atairu’s images appear as beautiful aesthetic objects in their own right. Tumblr-coded, they look at first glance like Afrofuturist posters, glossy magazine photoshoots, or cosmetic advertising campaigns. In the text-to-image Portrait of Mami Wata (2023), which was inspired by Nigerian folklore, a Black, thalassic goddess seems to have just emerged from the ocean, her head crowned by a frothing net of scaly platinum braids.

All this beauty is dripping with ambivalence. “It’s not just a pretty image of a Black girl made using an algorithm,” she says. “It’s more critical.” In other words, Atairu seizes on some viewers’ desire for “Black girl” beauty without complication. Her project situates the digital ethereality of AI against the grisly realities of the commodification of Black people, subverting the histories of colonialism and capitalism that made the technology possible (and profitable).

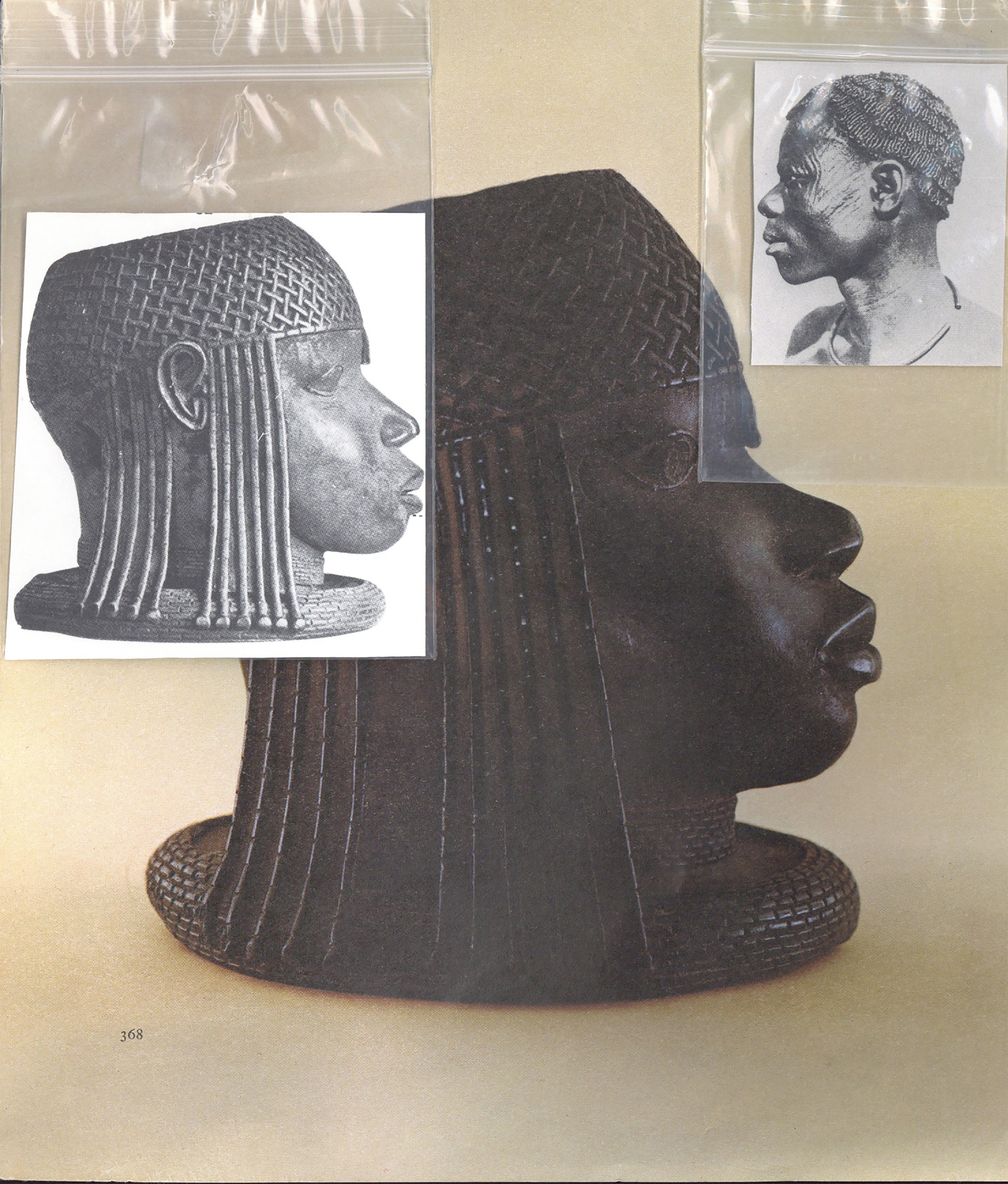

Atairu’s work goes beyond the realm of photography. For To the Hand (2023), a recent commissioned installation at the Shed, in New York, Atairu used 3D printing metal, bronzeFill, clay, and StyleGAN2 to pursue her ongoing series Igùn, which imagines a continuation of the Benin Bronzes, speculating about what could have been if the British military had not invaded present-day Edo State, Nigeria, in 1897 and looted thousands of plaques and sculptures. The resulting deposition of the oba, or king, instigated decades of artistic decline in Atairu’s homeland through a lack of royal support for artists. “The Igùn project is much more related to colonialism and how museums have held on to these objects that are considered colonial loot—for over a century,” she says. While Atairu’s research-based art often comes with ancillary materials, including her own academic articles, the subjunctive is at the heart of her practice.

For all its allure, Atairu’s art resists the temptations of the technocapitalist aura, resists the myth of neutrality. Her beguiling pictures emerge tentatively from an algorithmic sea of racism, sexism, environmental degradation, surveillance, unfair labor practices, and other conditions we live with—but might one day live without.

All images courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257, “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”