Essays

How Ghana Became a Homeland for the African Diaspora

From Maya Angelou to Todd Gray, writers and artists from around the world have returned to Ghana in the decades since the country’s independence. What were they looking for?

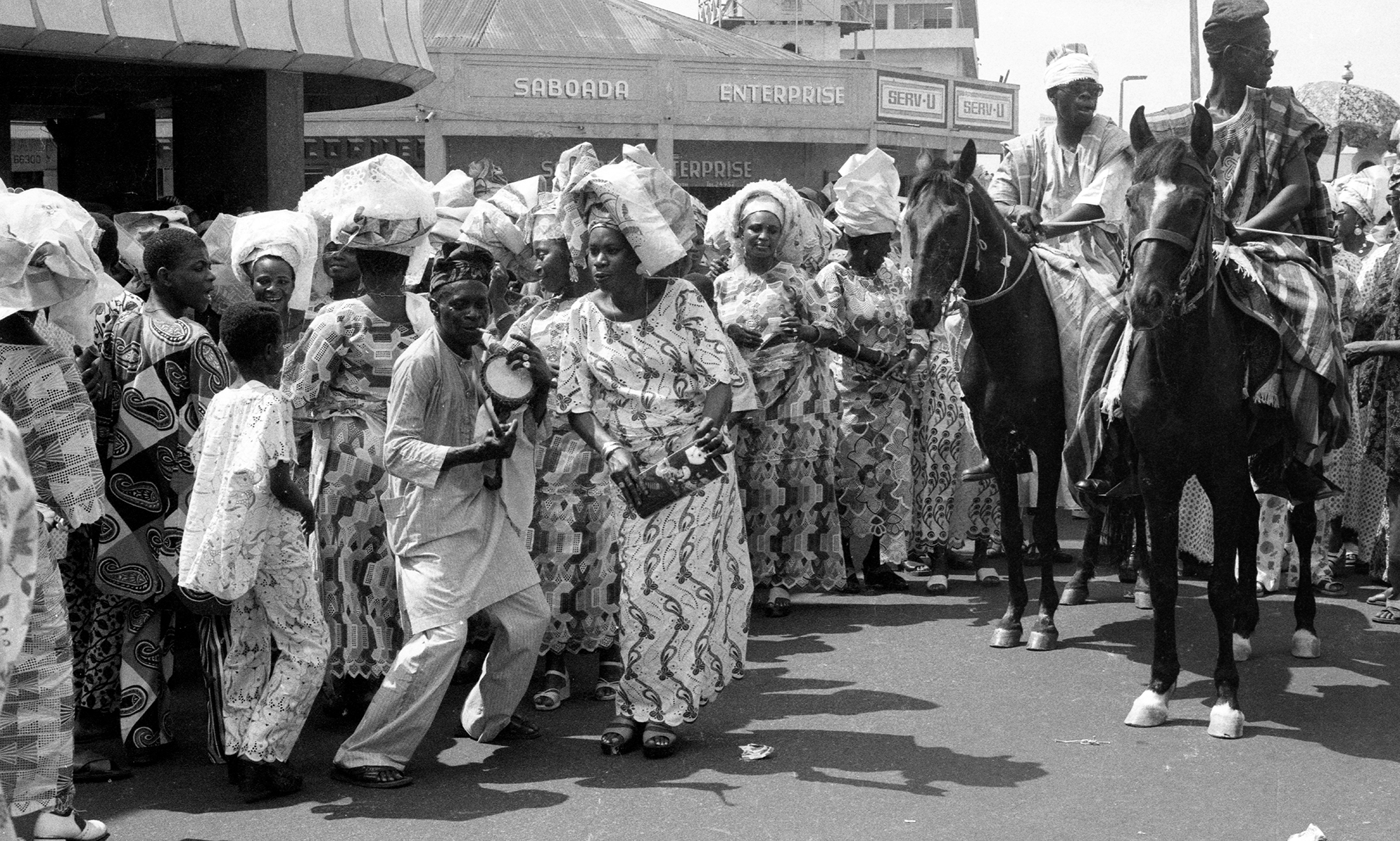

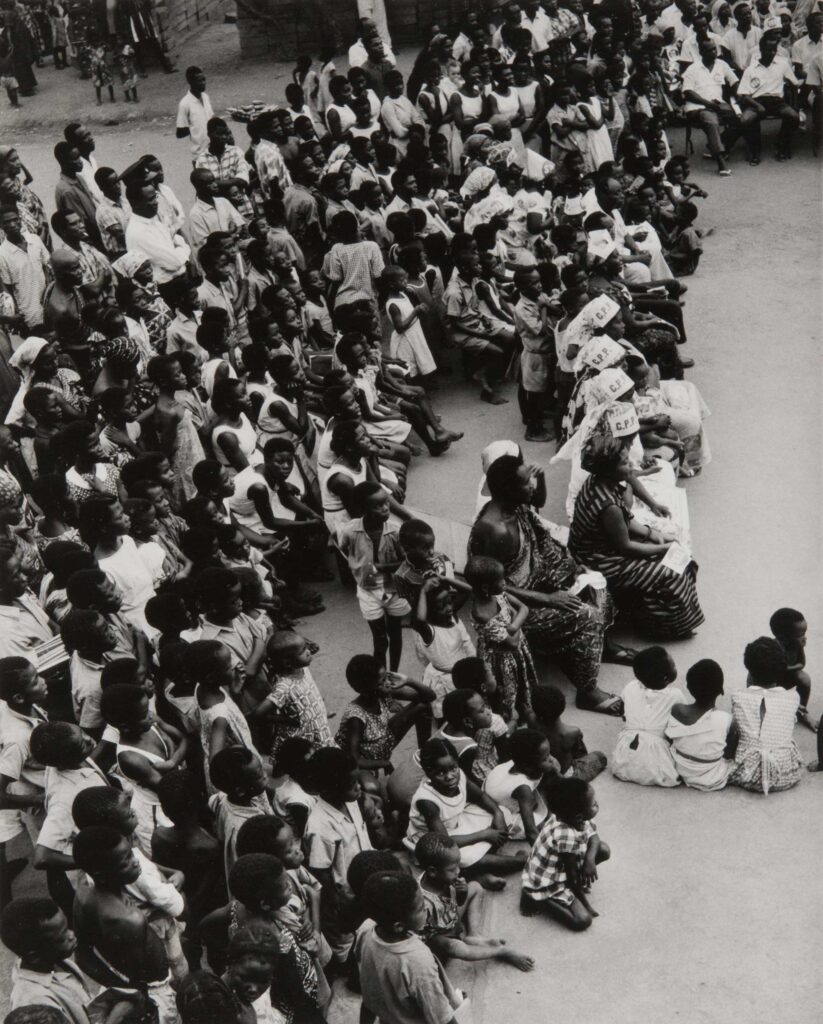

“Small Rally, Accra.” 1964. Townspeople, watching and listening with rapt attention, sit in a semicircle, oriented toward a speaker just outside the frame. It’s a mixed group: uniformed high-school girls in sleeveless white dresses, men in traditional woven cotton cloth worn toga style, others in long sleeves and slacks with a cigarette clasped between their lips. Children of all ages sit, squat, and crouch on the swept-dust floor. A juvenile rebel stares at the photographer—Paul Strand. A group of women sit on a bench in front. Signs pinned to their headscarves say “C.P.P.”: Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party.

The scene is an early glimpse at Nkrumah’s ongoing project of building a modern Ghana, a new country that piqued the attention of seemingly the whole world. Where the Cold War thinking held countries hostage to the narrow interest of Western white powers, Nkrumah and his peers in the so-called third world were putting forward an alternative global vision. Where Western leaders and their security details were cracking down on political protest and minority rights, Nkrumah himself embodied a continuation of the Pan-African struggle forged in the streets of Harlem, Philadelphia, and London.

© Aperture Foundation, Inc., and courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

It was easy, then, for many Black people in the diaspora to imagine Ghana as a home. Its name harkens back to the idea of a great African empire; its invitation to create a new African presence was compelling. This was the chance for people to go “back” to the motherland, roll up their sleeves, and help build the future. From Richard Wright’s Black Power (1954) and Maya Angelou’s All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes (1986) to Ekow Eshun’s Black Gold of the Sun (2005) and Saidiya Hartman’s Lose Your Mother (2007), writers and artists from the diaspora, having made journeys to Ghana, have composed distinctive travelogues about this possibility of a different world. They came to explore and see where they might fit in. This place of ideal perfection would provide a familial embrace. “We had come to Africa from our varying starting places and with myriad motives, gaping with hungers, some more ravenous than others,” Angelou writes in All God’s Children, “and we had little tolerance for understanding being ignored.”

The potential of a shared political and spiritual struggle stoked the impulse for homecoming, for healing and renewal. This was a society in transition. A society that brought together elements of the traditional and the contemporary, the old and the young, the spiritual and the scientific—all to fashion a modern technological behemoth. This is what Strand would spend four months and ten thousand miles attempting to capture in Ghana: An African Portrait (1976). It’s there in the cold power of the overwhelming metal structures, pipes, and concrete of the Tema Oil Refinery. And in the massive ships docked at the Tema harbor, promising the possibility of benefiting from a coastal proximity that had been a curse not long ago. Deeper inland, Strand preserves the mystery and majesty of ritual dance and incantations in Larteh, and with it, the timeless connection to the ancestors, land, and life force the people have always subsisted on.

© Aperture Foundation, Inc., and courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

© Aperture Foundation, Inc., and courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

Strand, with the blessing of the president, showed the world what Africa looked like. Ghana, he decided, was the best case study. I imagine the project as the first half of a before-and-after comparison, which meant to serve as evidence for awe-inspiring transformation to come. The country’s diversity, economic patterns, and environmental resources at the time adequately reflected conditions in other parts of the continent. But its more recent history—its complicity in the slave trade, supply of materials for the Industrial Revolution, and invaluable role in both world wars—linked it to the modern world. The people in Strand’s photographs appear determined to be exemplars of the “African personality,” demonstrating autochthonous values and characteristics in all their complexities, which would counter long-held racist ideas of the continent’s being a backward place.

“I was black and they were black,” Wright wrote of his experience in Ghana, “but my blackness did not help me.” Many returnees do not know the specific location of their roots on the continent, and their choice of Ghana is often attributable to a sense of ease: the use of English, and the relatively high quality of infrastructure and amenities. Rather than Ghanaians ready to welcome long-lost siblings, seekers met locals who knew little of their plight. The years apart and differing histories had made lasting marks. Culturally, Ghanaians found little in common with the goals of the Black American and British arrivals. Where children of the diaspora sought remnants and an understanding of their historical roots—hopefully untouched by Western elements—they discovered a Ghana detached from a meaningful engagement with the darker elements of its own history, betraying a narrower conception of what connected them. The wound of belonging festered, and as Angelou points out, the disappointed returnees “didn’t want to know that they had not come home, but had left one familiar place of painful memory for another strange place.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

What made the place strange was the apparent amnesia on the part of Ghanaians about the slave trade. The elephant in the room was the human in the barracoon. At the peak of the slave trade, in the eighteenth century, nearly a million slaves were shipped to the New World from Ghana alone. To Ghanaians like me, the slave trade is often thought of as a tragedy from outside that happened to us. Ghanaian schoolchildren took excursions to the castles at Cape Coast and Elmina to learn about how the white man tricked our ancestors. But, as Hartman points out, the largest slave market feeding the ravenous appetite of the trans-Saharan, transatlantic, and African slave trades was located not in the castles (the domain of Europeans, where returnees and tourists are shepherded to reflect) but, instead, in the town of Salaga, some 250 miles from the coast.

Ghanaian history has always felt to me like a black box. My elementary-school curriculum focused on how Ghana got its colonial name, the Gold Coast (skirting the fact that it exported far more slaves than gold), and extolled the achievements of select individuals, then covered the arrival of Europeans, debating the pros and cons of colonialism. Despite Ghanaians’ repeated citing of the Sankofa ethic to remember the past, it seems our desire has been to look forward, and to silence the sordid history. It is in the work of our artists, and Black artists from the diaspora, that a fuller sense of who we are, and who we have been, remains preserved.

In this vein, thinking “early Ghana” brings up images of Accra in the 1960s and 1970s. Of bell bottoms, high-heeled shoes, and Afros. The smell of Ghanaian printed cloth and heat. No one quite captured the feeling of optimism lighting up Ghanaians like the photographer James Barnor. Beginning in the 1950s, Barnor pictured the sense that everyone had a role to play in building not just the country of Ghana but a free, self-sufficient, and productive Black society. The era is, perhaps, embodied best by the dashing, modern women who stopped by his Ever Young studio, located in the Jamestown area of Accra, adorned in their Sunday finery—hair curled out or flattened and swept into a bun with perfect sheen, opera gloves caressing their arms, their most prized earrings dangling over their shoulders. Following a sojourn in the United Kingdom, where he made fashion portraits and covers for South Africa’s Drum magazine, Barnor returned to Ghana in the late 1960s and set up the country’s first color photography lab.

Barnor’s scenes from his return to Ghana portray the breadth of urban experiences.

Where Barnor’s previous work had been in the studio, the scenes from his return to Ghana portray the breadth of urban experiences. The aspirational images with fanciful, extravagant backdrops are replaced with energetic, unvarnished landscapes of a young nation: the loneliness of an empty bus stop illuminated by a trenchant sun, the vibrancy of a troupe of traditional dancers and drummers performing for a mesmerized crowd, the overjoyed demeanor and gaiety of revelers.

Not long after, the country would fall on hard times. Following a succession of coups and countercoups, Ghana’s economy crashed. The party ended. The state’s attention would turn from the dream of building a Black global capital. Some claim that Ghana was broke because Nkrumah spent all its money trying to help other African countries fight for their independence. Yet a connection to Black culture in the arts worldwide, particularly music and the resilient blues ethos, would in times of desperation serve as a balm for many Ghanaians. Jazz and reggae would inform highlife and hiplife, and Black comedies would inspire the concert parties staged in towns and villages across the country.

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

Throughout difficult economic times and military dictatorships, the natural charisma of the country and this sense of hope and possibility remained. This atmosphere creates for a mysterious, organic feeling that has continued to draw the children of Ghana to itself, over and over again. This is the experience the British Ghanaian writer and curator Ekow Eshun describes in Black Gold of the Sun. In 2002, he decides to visit Ghana, in the hope that it might help him “become whole again.” In London, at the age of thirty-three, he has been experiencing nightmares of lynch mobs chasing him. He wonders if it is the separation from Ghana—the land of his parents, and a place where he lived for part of his childhood—that is causing this pain.

Wherever he looks in Ghana, however, he finds the world from which he is ostensibly escaping. At the cool bars, the songs he hears are the same ones topping the pop charts in London and the United States. The way hip young people dress mirrors the images they see of hip-hop acts and vixens in Western music videos. Far from being a reprieve from the vagaries of the West, he finds that Ghana is actually an integral and key hub in the global exchange of materials and culture. And also history. Eshun’s trip to Ghana is soured when he learns that his great-great great-great-great-grandfather had, around the 1750s, arrived from the Netherlands as a slaver. Worse still, the man’s son, whose mother was a Black local, also became a slave trader when his father returned to Europe. What is this discovery like? “The disgust is overpowering,” he writes. “You wonder what kind of temperament it took to be a slave trader. And whether the responsibility for his actions runs through your blood.”

The loss and the survival, the mourning and the celebration, the local and the global—how can it all be held together? This is one of the central questions posed by the American artist Todd Gray. For the last seventeen years, Gray has lived between Ghana and the United States, meditating on the painful but strong poetic connection that exists between these places. Gray first visited Ghana as a photographer working with Stevie Wonder. When Wonder suggested that Ghana was their shared homeland, Gray responded that he didn’t even know who his great-grandfather was, so he couldn’t say. And yet, he told me recently, “Stevie made a strong case in the poetic sense that because of the Atlantic passage, and the route from the Gold Coast to the Americas, this was the point of departure for many of us.” He returned on his own and enjoyed the tranquility of being “invisible” in a Black-majority culture. “The vibe and the relationships were different,” Gray says. “When you walk into a place, you are just who you are. I felt at ease.”

Today, as in the late 1960s, there are initiatives from the Ghanaian state promoting return and efforts to encourage people in the diaspora to engage with the country’s history once again. Unfortunately, it all feels like a gimmick—a McKinsey consulting deck estimating how much money the state of Ghana could generate from its “heritage” rather than a meaningful attempt to rebuild and strengthen relationships. Wright or Angelou might be discouraged from making it past the fancy bars and restaurants of contemporary Accra’s Osu neighborhood, where photographs of encounters with celebrities go viral.

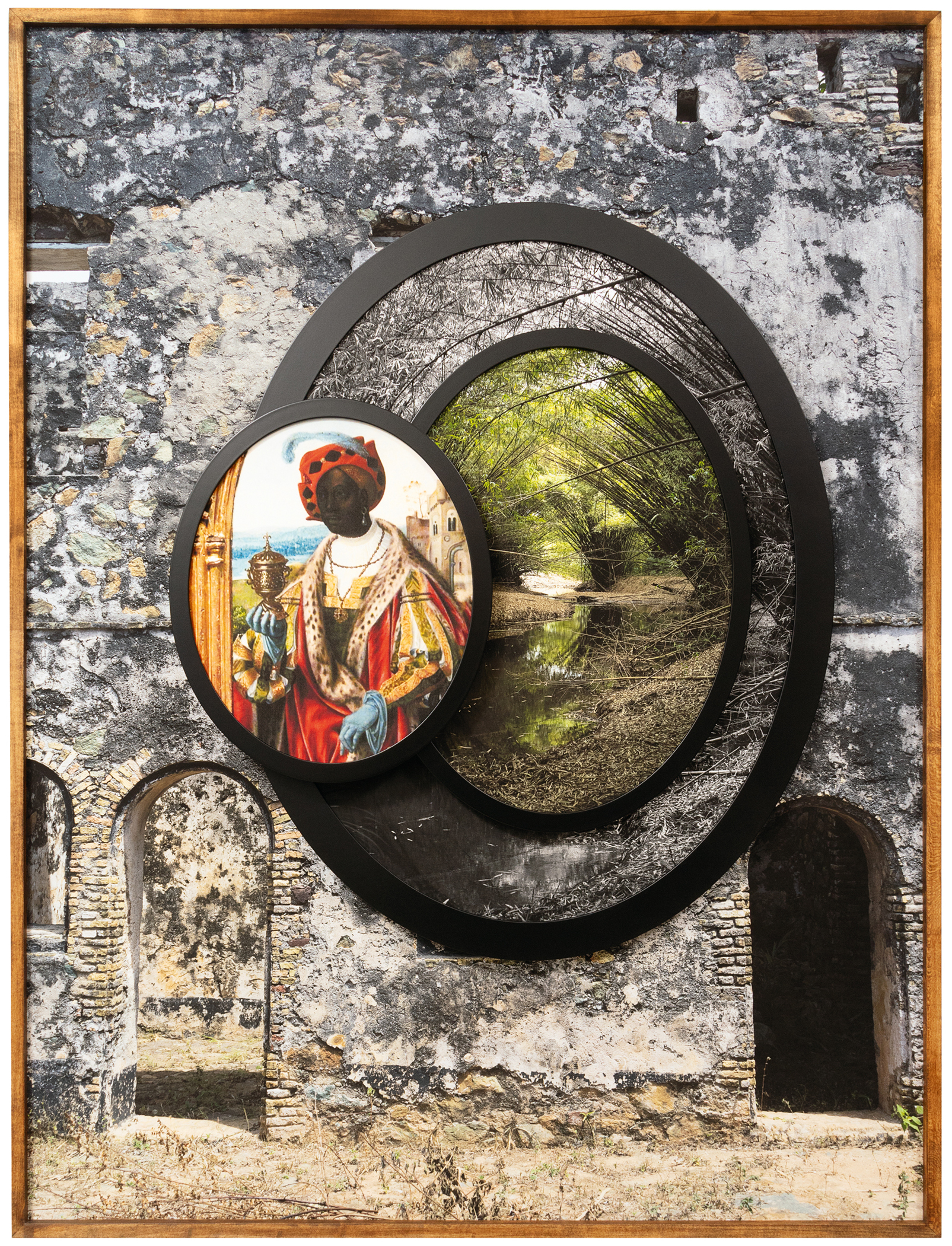

Todd Gray, Green Green, 2023

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York

Projects such as the new Pan African Heritage Museum are thriving. The long-standing Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, and other academic spaces that welcome thinkers from the larger Black world, continues to churn out thought-provoking scholarship on Black futures. Starry-eyed students from historically Black colleges and universities, Black Peace Corps volunteers, and Fulbright participants arrive at Kotoka Airport in steady supply. Courageous and idealistic individuals land on the shores of the country each day with little but the embers of that moment of promise—of an escape from a racist world that holds no hope for them; of a land still entwined with ancient African ways and practices that can nourish the soul. Many have set up charities, schools, or other beneficial initiatives and go on with their quiet presence and enduring work.

From the inside looking out, it’s the return to this vision of what can be that is most important. It’s the reminder from Wright and Angelou, Eshun and Hartman of the dream and what could be possible if we are open to new perspectives. Todd Gray’s photographic sculpture Green Green (2023) provokes such wonderings about envisioning that future with the turbulent present as a starting point. In it, an image on the left of marshy waterways abuts one on the right showing a segment of a wall. The first is along a slave trail leading down to a slave castle. The second is from Elmina Castle. Nevertheless, there is a calming, meditative beauty to the waterway. You imagine the water gliding along in tranquility, and the multitude of creatures put at ease by serene birdsong. In the scene, illuminated as it is by the sun, one senses the fecundity of life, the possibility of a welcome, an Edenic embrace, an opportunity for new beginnings.

You can’t get a sense of Gray’s work if you see it from only one place. “I do that to make the viewer always have to move, to always be making meaning, and to constantly have to appraise,” he says. What does it mean to leave and to return? To change and to see change? At the center of Green Green is a man on a boat, rowing into a grove. He’s going into the past. He’s going into the future. He recalls the ancient African idea of a ferryman taking the dead across to the other side. In Green Green, is this other side a point of arrival or departure? No matter. The vision and hope of the Black Atlantic Future is an undying one. And as Ekow Eshun realizes toward the end of his travels in Ghana, “You never truly leave home. It stays with you even in the worst of times.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”