Interviews

How John Akomfrah’s Videos Tell a Story of Migration and Belonging

The acclaimed filmmaker, who will represent the United Kingdom in the 2024 Venice Biennale, speaks about the restless ghosts of Ghana’s history.

Photograph by Liz Johnson Artur for Aperture

For more than four decades, John Akomfrah has sought to tell myriad tales of migration and belonging. Akomfrah left Ghana for the UK as a young child after the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, was overthrown in the 1966 coup, which put his activist mother’s life in danger. In a 2012 interview for The Guardian, Akomfrah stated that his father’s death was due in part to the turmoil and “struggle leading up to the coup.” In 1982, he and a group of peers cofounded the organization Black Audio Film Collective. Inspired and energized by the work of theorists such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall, the collective addressed landmark moments in British history with an astute critical gaze, connecting the discrimination that migrants to England faced to the malaise and postindustrial decline of the country.

After the collective dissolved in 1998, Akomfrah continued to write and direct films and video essays, including the three-screen installation The Unfinished Conversation (2012) and The Stuart Hall Project (2013), both based on the life and work of the pioneering postcolonial scholar. In 2019, Akomfrah was one of six artists invited to show at Ghana’s first-ever pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and in 2024 he will represent Great Britain at the international event. Akomfrah’s practice and oeuvre is testament to the notion of hybridity: his project is to name the political ghosts and specters that haunt the present day, to confront complex histories—no matter how violent or gruesome—and tackle the bad spirits. Last spring, Akomfrah spoke from London with the writer Vanessa Peterson and the artist Lyle Ashton Harris about the dialogues between Ghana and its diaspora.

Vanessa Peterson: An interesting place to start would be to talk about your first narrative feature film, Testament (1988), which was shot in Ghana and England. The film follows Abena, a political exile who returns to Ghana after the overthrow of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, to interview the German director Werner Herzog, who is also in the country, shooting Cobra Verde. Abena also seeks to reunite with her former political colleagues. I’d be curious to know what led you to making Testament, and the origins of the film.

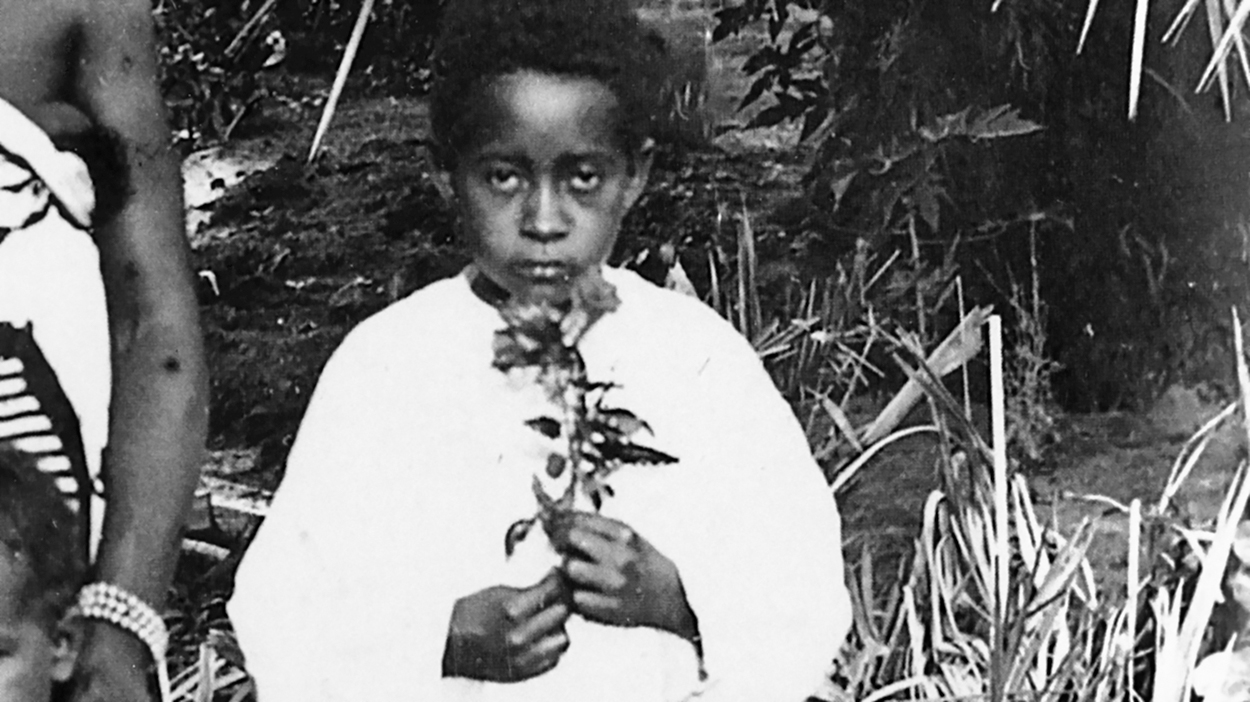

John Akomfrah: The paradox of the film was that even though I am the most Ghanaian of Ghanaians—born in the year of independence, parents were anticolonial activists completely committed to that project of the transfer of power, both political and cultural—even though all of that was me, and continues to be me, I hadn’t really thought about making that film. I, like the character, was in flight from that subject, for all kinds of emotional and psychic reasons. But it was inescapable at a certain point. Even though you might suppose that the reluctance to engage with Ghana was a reluctance to engage with Africa in general, that was the very opposite of the case. I had been tracking and following African cinema and its histories for many years.

I was in Ouagadougou for the Pan African Film Festival when a number of other filmmakers, Haile Gerima being one of them, said to me: “Did you know that Werner Herzog is in Ghana making a film? What are you doing sitting here? Why don’t you go and make one, rather than allowing that guy to do your story?” I was like, “Okay. I’m not sure he’s going to do my story, but I get the point.” It was really via Pan-Africanism that I returned to the nation, and very specifically, it was the urgings of other filmmakers who were all part of that Pan-African movement that took me there.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Lyle Ashton Harris: I saw Testament when you showed it at CalArts. It seems prescient, if you think about the book White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa (2021) by Susan Williams, who writes about the Cold War–era involvement of the United States in assassinations and coups in newly independent African states. You address a lot of similar themes.

Akomfrah: One of the reasons for avoiding the subject was precisely to do with the terrain that White Malice covers. There were a number of living rooms in that African revolution, and I happened to be in probably the epicenter of the living rooms, because both my parents were involved with it, working for the Convention People’s Party, founded by Nkrumah in 1944. My mother was at the university, the ideological institute that the film deals with. Many of the subjects later covered by Susan Williams were ones I was intimately familiar with. For instance, I remember having a conversation with my mom in the ’70s when I first read Malcolm X’s autobiography. She must have seen it on my desk. She said, “Oh, you’re reading Malcolm X?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “Oh, I knew him.” That blew me away.

Since the ’70s, I had known that there were these forces at play on our continent, and specifically in Ghana. I didn’t want to go there.

Peterson: Testament makes me think of autofiction—it’s fictional, but it’s also playing on deeply biographical elements. Sometimes it’s the only way to tell a story, especially one filled with pain and dislocation. To me, that is what writing and directing Testament was for you. Did you feel it was a way for you to reckon with your familial circumstances, as well as the legacies of Ghana’s turbulent politics? To guard against a sense of amnesia that comes with the passing of time?

Akomfrah: Yes, of course. What’s been odd for me since we made it in 1987 is that it became a kind of subgenre of African filmmaking. This “returning” film. There were so many films afterward of people returning for one reason or another.

Ashton Harris: Such as Sankofa by Haile Gerima. In actuality, you anticipated his film.

Akomfrah: Yes. That’s very odd. I hadn’t even thought about that. But it is true. Including the grandmaster Haile himself. Basically, this primal scene of African suffering with its tragedies and its accidents. It was almost Greek in profile, in the sense that there were forces at play that seemed bigger than individuals. One of the ways in which I think many of us exilic kids came to deal with this was via fiction and filmmaking. Many people seemed committed to the idea that there was this hidden country that they felt—a country of ghosts, if you like—where they felt brave enough to go only through cinema or the moving image. That was an extraordinary thing.

Ashton Harris: With regard to returning-to-Ghana narratives in literature, we can also look at travelogues by Richard Wright, Saidiya Hartman, and Ekow Eshun.

Akomfrah: Certainly. There was a period when very many people who had either left as children or came of age and were old enough to begin to chart their connections with the continent—for them the moving image was a very good source, as well as literature. I think in the “war zone of memories” here, as Testament very clearly says. And in that war zone, the politics of location and identities is crucial. Malcolm was prophetic in all kinds of ways, not just for himself but for my mother and our institute. A year after he died, the military coup happened in Ghana, on March 6, 1966. Everything that that moment stood for was wiped away. You can say that, had Malcolm been alive in ’66, and had he wanted to be in Ghana, none of the conditions that made it possible for him to be there would have existed. He wouldn’t have been allowed in because the military would have seen him as a troublemaker. Many Pan-African institutions had been shut down for being communist and Marxist. He was prophetic in a way that he hadn’t anticipated, because when he spoke about his end, he was actually speaking about the end of a lot more than that.

Installation view of The Unfinished Conversation, 2012, Museum of Modern Art, NewYork. Video,

45 minutes, color, sound

Courtesy Art Resource, NY

Peterson: And then your life suddenly changed.

Akomfrah: Yes. Following my father’s death, we were quite literally in flight, and through a circuitous route via the US, we arrived in this country, begging for shelter, which is so bizarre to me, then and now. The thing that was bizarre to me was the fear of being in Ghana. The fear that something terrible was about to happen to us was palpable. I was very young, but I knew it. I could feel it. Let no one tell you fear does not have a personality, an ontology. It really does. Ghosts do fucking exist, and they do stuff. I was aware, palpably, that we were being stalked by something. I mean, phantom is too innocent a word. A kind of ogre. And nothing but flight would save us. I was absolutely relieved when we arrived here, in a way that I think people who now go on boats to leave, to come to this country, would know, would understand. The palpable sense of relief was extraordinary for me.

We arrived here in the late ’60s and continued to try to make this place a home. At the time, we consciously tried to create an Accra in London, in our house, which would stand for the Accra that I left. In this weird Faustian bargain that I think most exilic figures make with the historical, you slice a piece of it, a manageable piece, you construct a tableau either in your bedroom or your house or your new town, and that becomes your version of where you’ve left.

Having been brought up in a Pan-African environment, a lot of things were easier for me to navigate than they might appear at first.

Peterson: Did you speak about Ghana?

Akomfrah: We spoke about narratives. I remember my mother being obsessed with the narratives of betrayal—who did what, when; how this happened; who was responsible. And it wasn’t just a regional thing. It wasn’t just a local thing. It was a continental thing. We were in the space of every defeated, every vanquished, every political uprising that didn’t happen. I’m including in this all of the ones that were to be, whether it’s Angola or South Africa or Zimbabwe—it was just all these places of defeat and the vanquished, which became our country and our continent. In London, you met other people who’d lost their home and were running from violence. There is this incredible, ironic reversal in that period, where you meet all of these folks who had left to go and throw out the British, coming, begging, cap in hand to the British to take them on.

Ashton Harris: I’ve used a quote of yours many times, and it has been a guiding force to me: “The problem with the Black avant-garde is that we’re constantly having to reproduce itself, because we don’t actually protect it. We don’t give a citation. We don’t acknowledge it.” Starting with Testament, there’s a thread through all of your work in terms of its radical project of, to Vanessa’s point, anti-amnesia. How did you emerge? Why were you chosen by Stuart to be the architect of The Unfinished Conversation or The Stuart Hall Project?

Akomfrah: Growing up in a house of the vanquished, of the dismissed, I am aware of what I would call the thing to come, which is the thing that stalks all powerless lives. It’s the coming of the disaster, really. All of that made me comfortable with the unpopular. I never had a problem with the avant-garde because many of its conceits had organized my life: asymmetry, bricolage, nonlinearity.

Stuart was one of the few who made generational sense to us. I think it’s to do with his purchase on this place, because he got here when he was young and had worked his way into many institutions. He became a product of all of those. When he spoke, we could feel that he inhabited several living rooms at the same time. I wasn’t born here, but I always felt more connected with people of my generation here. I didn’t see what I was doing as being something from a Ghanaian kid. I knew that I had to make the transition from a Ghanaian kid to a Black British one. But at the same time (and this is the important thing that the people who usually call me Ghanaian are not aware of ), most of my generation were doing exactly the same thing. Because their parents had come from somewhere else. It fell on them, as the children, to deliver on the promise of post-migrancy. Sometimes people say to me, “Oh, it’s so interesting that you understood Caribbean culture so well that you’d make Handsworth Songs.” What do you mean? It became clear that Black Britishness was going to be arrived at by a mélange of Caribbean and West African culture.

Having been husbanded, schooled, brought up, and nurtured in a Pan-African environment, a lot of things were easier for me to navigate than they might appear at first. And the navigation wasn’t at the expense of being Ghanaian, because no one could remove that. Even as a seven- year-old, I knew that I was forever marked by that place. I knew things that everyone who lives abroad has to contend with. It’s typical to meet somebody from the Caribbean who goes back to where they grew up and realizes that they embody everything that that place has lost. The place itself has moved on and doesn’t cherish anymore the kinds of fruit that were there that you liked. All that’s gone. You have, in a very real sense, become a custodian for that lost life.

Peterson: In relation to being a custodian, there are specific references to being Ga—an ethnic group from the Greater Accra region—throughout Testament. You reference rivers in relation to memory, for instance. Can you speak more to your relationship with your Ga heritage, and how memory and legacy appear in your work?

Akomfrah: I am aware of huge strands of Ghanaian life that only people like me embody, because it’s gone. I remember a time when it was common knowledge that as Ga people, people of the rivers, that our gods were the rivers. I realized that once you lose your memories, everything else will be gone. One of the things I was certain about as a grandson of a Ga elder was what those things mean—what it is to be the high priest of a river, what it means to be an herbalist in a certain kind of tradition. Testament was trying to make an oblique reference to a familial past that may not make sense to everybody else. I think there was all kinds of what would now be called ecological consciousness that being Ga entailed. There was an ascetic, frugal relationship with our environment. Quite a lot of it disappears, because the frugality of it was one of the reasons people wanted independence—they were sick of living these frugal lives.

Peterson: I’m also Ga. My family are from La and Jamestown, where various colonial administrations, such as the British, were based. We’ve been speaking about anti-amnesia, and now initiatives, such as Year of the Return—when in 2019 Ghana invited African diasporans to return to the country and commemorate four centuries since the beginning of transatlantic slavery—have been put in place to regather and bring those in the United States back to the continent.

Akomfrah: One of my relations with the country at the moment is via a morbid symptom, which is that I go to Ghana frequently, usually to bury someone or to attend memorials. My father had six sisters, five of whom have now passed away in the last fifteen years. I’ve returned to La every two years or so to bury someone. I flew into Accra a few years ago, and it happened to coincide with the Year of the Return project. The airport was full of hundreds of people—it was the most extraordinary thing. It reminded me of something that I’ve always felt. We talk about ghosting, phantoms, and unseen guests. There’s a real sense in which these figures and apparitions have a right to that landscape. Many generations of people may not necessarily be from Accra but passed through Accra on their journey elsewhere. We’re one of these strange spaces where I think our sense of sovereignty needs to be a postmodern one. Our sovereignty cannot simply lie with the living any more than it can lie with just the dead of that place—we have several millions of dead elsewhere who are of that place.

Akufo-Addo, Ghana’s president, may have just had economic logic with Year of the Return. Whatever reasons they have, cynical or otherwise, fine. The important thing was that it happened, because someone needed to swing that door of no return the other way. It reduced me to tears because I knew that there would be a day when it wasn’t just Maya Angelou and a few friends or Malcolm X who visited—there’d be thousands of people of African origin who feel connected to the place and feel it is indebted to them. And that’s right. Because it is. It’s indebted to them, in a sense that it has to open the door of memory.

All works courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

Peterson: On a granular note, I’d like to think about hybridity. This is a term that is often used to describe your work and practice. With your relative distance to the country, alongside your project of anti-amnesia, I would love to know what representing Ghana in 2019 at the Venice Biennale brought forth for you.

Akomfrah: The strange thing is that by 2019, a lot had been ironed out for me. Some of the creases of discomfort are gone. One is also aware of this question of temporality. Just about everybody who was involved in my being turfed out is gone. There’s no one alive who was an architect of the 1966 coup. So you’re aware of being slowly moved to the front of the queue. That seems to me to come with certain obligations. If you’ve known Nana Oforiatta Ayim, who curated the pavilion; David Adjaye, who designed it; or Okwui Enwezor, an advisor on the project, for as long as I had, and they ask, then you’re not just saying yes to a country; you’re also saying yes to an ambition of theirs to do something.

Nana made it clear that she was interested in this conversation between Ghana and its diaspora, the old and the young, midcareer and emerging artists. I am, too. I might not live in Ghana, but I am Ghanaian in one very important sense, which is that its future matters to me. I’ve got relatives who still live there, cousins and aunties. I have very real connections that are ongoing, which make demands on me. For those reasons alone, when someone decides to pull me into a space called the Ghana Pavilion, I thought, Well, I’m not officially, but I’m sort of already there.

If you’d told the younger me that there would be a time when I’d be happy with this, I would have shot you. There was just no way that I wanted to be owned by that place, because it had disowned us in a very violent way, and for me, that was the end of the story. I was quite happy for it to be that. The disavowal of the place or people, it was a disavowal of the connection—the presumed connection between me and it. Providing it didn’t try to acknowledge or claim me, I was quite happy for it to be there, doing its own thing. I’d even go there, but when I left, that was it. It’s like, Okay, you’re there and I’m here. Finished. It’s only recently that I’ve started to understand it. That places don’t let you go so easily.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”