Interviews

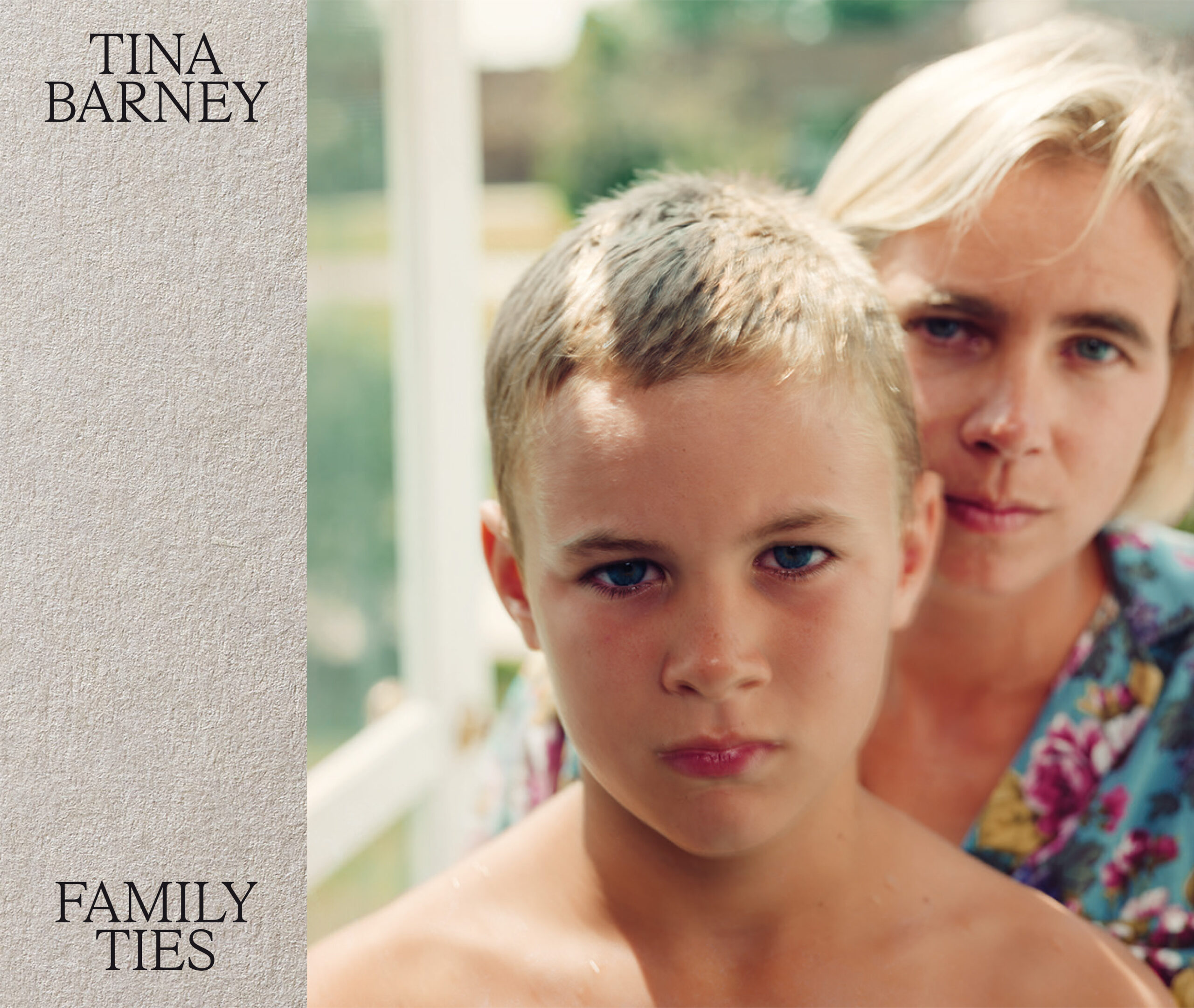

How Tina Barney Became an Astute Observer of the Upper Class

The photographer’s signature large-scale portraits show the secret world of the haute bourgeoisie—and the way certain poses are handed down across generations.

In the late 1970s, Tina Barney began a decades-long exploration of the everyday but often hidden life of the New England upper class, of which she and her family belonged. Photographing close relatives and friends, she became an astute observer of the rituals common to the intergenerational summer gatherings held in picturesque homes along the East Coast. Developing her portraiture further in the 1980s, she began directing her subjects, giving an intimate scale to her large-format photographs. These personal, often surreal, scenes present a secret world of the haute bourgeoisie—a landscape of hidden tension found in microexpressions and in, what Barney calls, the subtle gestures of “disruption” that belie the dreamlike worlds of patrician tableaux.

This year, Aperture published Family Ties, which collects sixty large-format portraits from the three decades that defined Barney’s career. The volume accompanies the first retrospective exhibition of the artist in Europe at the Jeu de Paume, Paris. Here, in an interview from the book, Aperture’s executive director Sarah Meister speaks with Barney on her beginnings with the medium, the transition to working in color, and her approach to large-format photography and working on assignment.

Sarah Hermanson Meister: I thought we could begin by exploring some of your earliest connections with photography, including the fact that your grandfather was an amateur photographer.

Tina Barney: He photographed us whenever he came over with all different kinds of cameras. I have his 4-by-5 glass-plate negatives from the First World War and some of his photographs.

Meister: Your mother was a model. Do you remember seeing her modeling photographs around the house?

Barney: No, she only showed them to us when we were adults. I think she was kind of hiding them. She stopped modeling when she married my father.

Meister: Did you know she was a model?

Barney: Oh yes. She was incredibly stylish. She brought me to see the collections in Paris where I saw memorable shows, including Yves Saint Laurent’s first fashion show when I was sixteen. So, fashion has really been a part of my life.

Meister: In 1972 you joined the Junior Associates at MoMA and started volunteering there in the Department of Photography. Do you remember when you were first aware of someone who approached photography as an artist, unlike your grandfather for whom it was a hobby?

Barney: When my friend Ali Anderson suggested I become a volunteer, I had barely heard of any fine-art photographers. I knew nothing. My first memory of being at MoMA was when I saw a man showing another man a photograph: It was John Szarkowski showing someone a Ken Josephson photograph. There was a woman there that I befriended and she mentioned Ansel Adams, but I had never heard of him. She started talking about the two photo galleries in New York at the time and that’s how it all began. I went to Witkin Gallery and to Light Gallery. Marvin Heiferman was at Light. Jain Kelly, who worked at Witkin, basically started teaching me the history of photography. That is when I started buying photographs.

Meister: Do you remember what you were buying?

Barney: Imogen Cunningham, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank. Just the greatest hits. I have the bills—$150 was the most I spent.

Meister: Pretty good investments. Do you still have the pictures?

Barney: Yes. I also saw the great Friedlander, Arbus, Winogrand exhibition at MoMA in 1967 [New Documents]. It was like seeing God, let’s put it that way. I think it had a great deal to do with the subject matter of Diane Arbus, but also the way these three people were photographing in such different ways. I started looking at photographs more and more, and then I went to Sun Valley and started making my own pictures.

Meister: When you moved to Sun Valley, Idaho, in 1974, you started taking classes at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities [now Sun Valley Museum of Art]. What was that experience like?

Barney: The director of the photo department, Cherie Hiser, who came from Aspen, was a sort of goddess—the heroine of photography at that time. She was a combination of Marilyn Monroe and Nan Goldin: a great character. Peter de Lory was my first teacher. And after Peter left, Mark Klett came in to teach color and Ellen Manchester became the director. That is when JoAnn Verburg, Ellen Manchester, and Mark Klett were making their Rephotographic Survey Project. That was very important to me, both because Mark was working with a 4-by-5 camera and because of their commitment to returning to the same place multiple times. They were great teachers.

The setup was quite primitive: you would walk in, in your shorts or ski boots, and famous photographers would come there and teach. It was an incredible environment. Not only did they talk about photography, but about literature, philosophy, and books that I had never even heard of before. So, basically, I was educating myself. I didn’t finish college. I read a lot and learned a great deal besides printing and doing my own work. My own work didn’t really develop there because there was nothing to photograph. It came very slowly after I left.

Tina Barney: Family Ties

65.00

$65.00Add to cart

Meister: Like most photographers in the 1970s, you began working in black and white. Why was that, and how did you decide to shift to color?

Barney: I have a feeling that the change might have come from color being a fad at that time. When I was making black-and-white work, it really was like speaking another language. I would actually think about the transfer into black and white, I would imagine it in my mind. With black-and-white photography you’re dealing with tones and shadow, or light and dark, as opposed to color. I feel like color is a more natural translation of reality.

Meister: So you don’t make that translation when you’re working in color?

Barney: No. Actually, it’s something I don’t think about. This is what it might be like: English is my native language and when I speak it, I don’t do a translation. But if I speak French or Italian, there’s a translation going on in this section of my brain, which fascinates me. I think that is what happens when I’m photographing in black and white.

Meister: Let’s turn to the question of format. What camera do you use?

Barney: Well, for almost as long as I can remember, I have photographed with a large-format camera. Those earliest pictures were 35mm, and I don’t think that I’ve gone back since 1982, except in moving imagery, which is a whole other topic. Large format is really my native tongue. It’s so much a part of me, it’s automatic for me now. One of the best parts about it is that it slows me down. I have a very fast- moving personality, which might sound great, but it’s not: I badly need to slow down. Those view cameras really do slow you down, which means thinking. I love the 8-by-10 because when I go under that dark cloth, it’s like a meditative process, which is just not part of my personality. Even though there might be other people around me, I concentrate when I’m under that dark cloth.

Meister: How did you learn to work with a 4-by-5 camera?

Barney: I must have gone out and bought one right as I was leaving Sun Valley. When I left, I knew nothing about that format, and I had no teachers and nobody to ask. I don’t even know how I learned to use it—the same Toyo camera I have today—when I got to New York. In the beginning, I had the rail of the camera showing in the picture because I didn’t even know how to open it up. I really did it by trial and error. I don’t remember how I got the film developed or where it was printed or any of those things.

Meister: You have spoken about learning to make larger prints in Sun Valley . . .

Barney: Peter de Lory taught us how to do that in black and white and Wanda Hammerbeck came in and talked about a lab in Berkeley that Richard Misrach used to make 30-by-40-inch color prints. Around that time, I went to Houston and met Anne Tucker [then photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts]. She told me about a place where they could make an even bigger print—48-by-60 inches. It was a really big deal to do that. Before that I don’t think the paper had been invented. That’s when everything started happening.

Meister: Tell me more about meeting Anne Tucker.

Barney: I went to Houston [from Sun Valley] with another friend who was a painter. She wanted to become famous, too. When we saw Anne, we rolled the prints out on the floor. She said, “Wait a minute,” and then ran out in the hallway and started getting everybody in the department to come in and said, “You’ve got to see these pictures.” Then she phoned her friend Marti Mayo who was working at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston and said, “Marti, you’ve got to come over and see these.” I sat there and said, “OK, I think I’m dreaming,” because that is what every artist in the universe dreams of.

Anne said, “You’ve got to call this guy John Pultz at MoMA. He’s having a show about big pictures.” I called MoMA and said, “Hi, I have a picture I’d like to show to you.” I don’t know how I even found the phone number. While I was on vacation with my kids, the phone rang and it was John Pultz. He said, “We’d like to show your picture [Sunday New York Times] at the Museum of Modern Art.”

I didn’t even go to the opening because I was in Sun Valley. I never saw it hanging there. That’s how it happened.

Tina Barney, Sunday New York Times, 1982

Meister: Let’s talk about Sunday New York Times, which you made less than a year before it appeared in that exhibition.

Barney: You know, when I look at that picture—I just looked at it the other day, I don’t see it often—the resolution is so incredible. That’s what is amazing. I don’t know how I did it because there are ten people in the picture and they’re all running around like crazy idiots. I asked the father to sit at the head of the table, I counted one thousand, two thousand, three thousand . . . and he held still. That was just enough. I had no idea what I was doing counting those seconds. I was so untechnical: I just guessed.

Meister: About the gallerist Janet Borden . . .

Barney: I have to mention Janet because she is definitely the most important person in my career. You know how people say someone made them? She made me. She had the imagination and the personality to put me in a context I think I could have totally missed. She knew the most far-out people. She went to Smith College, she was friends with actors that worked in The Wooster Group, she went to Rochester Institute of Technology. Every person she introduced me to was cool and happening. I think that was very important because I could have been put in this category of “nice little portraiture,” you know?

Meister: How did you meet her?

Barney: She worked for Robert Freidus, and I must have heard about his gallery somehow. I bought a couple of pictures from her. Then, when I had the big pictures, I think I called her and said, “Would you like to look at these?” It took her a long time to get her own gallery, so at first she showed them out of her little apartment. One show was in a restaurant of a friend of hers, tacked up on the wall. Another was in a gallery, and you had to walk through another show that was so terrible to get to my show. I went to the opening and thought, Oh my God, I’m going to die. She introduced me to everyone. She knew all the curators and everybody in the photo world.

Meister: So, when your work was included in the Whitney Biennial in 1987, you had been working with Janet for a while?

Barney: I was very lucky because I was in quite a few shows in the 1980s, but the Whitney Museum was a big deal. My best friend in Sun Valley, Mary Rolland, who ran a gallery there, said, “You’ve got to show your work at the Boise Gallery of Art” [now Boise Art Museum]. I replied, “Oh, don’t be ridiculous,” but I sent Beverly, Jill and Polly and Sunday New York Times and they took them both. Patterson Sims was the judge and he gave me first prize. He was then a curator at the Whitney, and Lisa Phillips was also there. They took three of my pictures for that Whitney Biennial. The Starn twins [Doug and Mike] were in it too; it was an interesting show.

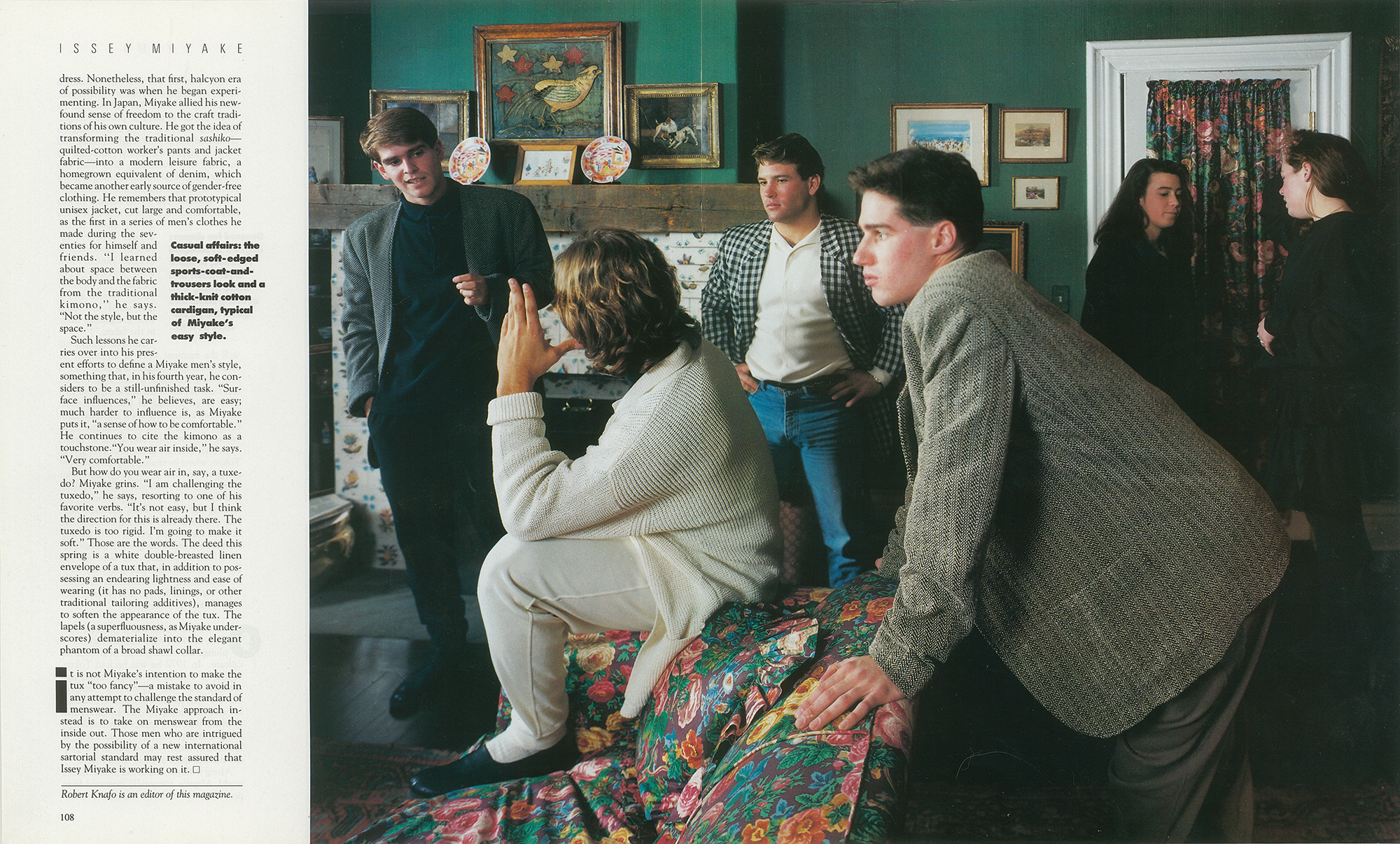

Meister: Shortly after the Biennial you did your first editorial assignment.

Barney: I think that was with Connoisseur magazine, which was fantastic. That came from Janet too. She knew the guy who was on the cover of it with Polly, my niece. The photograph was taken in my sister’s apartment. It was terrific. Issey Miyake clothes. I used my son in another picture. We had a blast. That was the first shoot I ever did and I was really nervous, but I loved it. In 1990 Michael Collins, one of my dearest friends who is now a photographer, was the picture editor of the Daily Telegraph magazine. He hired Larry Sultan, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, me, and many others to do editorial jobs all over the United States. I worked for him for a long time and it branched out into many more things. That was when I really started doing editorial work and I loved it. He sent me on the weirdest jobs you could ever imagine.

Meister: Bill Brandt once observed: “I hardly ever take photographs except on an assignment. It’s not that I do not get pleasure from the actual taking of photographs, but rather that the necessity of fulfilling a contract—the sheer having to do a job—supplies an incentive, without which the taking of photographs just for fun seems to leave the fun rather flat.” I feel as if I’ve heard you say something similar.

Barney: Well, that’s exactly how I feel. It’s almost like having an assignment in school that you enjoy and really want to do. Anyone who’s not an artist does not realize what it’s like to be an artist. You don’t jump out of bed every day and think, Oh boy, I have a lot of great ideas and I can’t wait to get out there. I always think you have to make inspiration come. You really sit around and start to think, What should I do every day?—which is not the most fun part of making art. The longer you keep doing it, the harder it gets to reinvent yourself each time. I’ve been lucky enough to do what I want and I really do enjoy it. Some of the pictures have ended up being really strong and some haven’t. But most of the time, because I’ve had such good choices, I’ve really enjoyed them.

Meister: Is it important to you that someone can tell whether a photograph was made on an editorial assignment?

Barney: No. To me they fit right in. The fact that they are from an assignment is like having an extra-spicy sauce on top of dinner. They’re a fun added attraction.

Meister: I’d like to ask you about the decision to shoot analog or digital.

Barney: When I first started using a digital camera in 2014, I did it because I thought, OK, this is what’s happening in the world and I sure don’t want to be out of it. I’d better damn well figure out what this is all about. I struggled with it. I made pictures, most of which were not successful at all. Now, when I do a fashion or commercial job, I struggle with my assistants, my agent, and the clients because they all want me to use film! This just started happening four or five years ago. I thought everybody was crazy: They don’t know the difference. Now it’s the first thing people ask, “Will she use film?” They don’t know the pain in the neck it is—let alone the cost—all the other equipment, plus a lot of other things, including finding an assistant who knows about view cameras.

I love the 8-by-10 because when I go under that dark cloth, it’s like a meditative process.

Meister: What do you think they’re after?

Barney: The main thing is they want my pictures that I’m doing for them to look like my own work. They think what defines my own work is the camera and film I’m using. I still think they’re crazy, but sometimes, I think they’re right. There are a couple of things you’re not going to get if you digitize that 4-by-5 or 8-by-10 negative. You’re not going to get that sort of edge—edges that are so sharp and fine and sort of false-looking. The other thing is that I think people don’t realize how much is out of focus in my view-camera work—and has been for the last forty years.

Meister: When you’re working with a digital camera, that kind of thing is not possible?

Barney: Right. There’s a softness to it. There’s also a color difference. There’s a pastel look to analog film. But it’s very hard to explain without actually looking at the image in front of you.

Meister: Could we talk about moving images for a moment?

Barney: Super 8 films are my really great love; they are very close to my heart. I always feel like a beginner and I’ll never get past that. If I had my way, I would just take the film and say, “Here, take it. This is what I love. We don’t need to make any sense out of it. There doesn’t have to be a story. I just love the way this looks.” This kind of vintage look is what I really love. I’ve tried to make many little films and I don’t think they’re successful or important, but I love the fact that they might be shown. Actually, one film that’s going to be shown at the Jeu de Paume is a VHS. So much time has gone by that it actually looks great. I mean, it’s just a mess. Forget about focus. I had this prehistoric sound system. I had no idea what I was doing, but I did it.

Meister: What did working with a moving image offer?

Barney: Because I just love looking at film. It’s like when you see something you like you say, “I want that too. I want to have that dress or make a cake that tastes like that.” It was basically that I wanted to try it. I also thought about recording the people I was photographing: imagine if you could hear what they were saying—not only because I’m so in love with anthropology and sociology—their accents, the intonation, the way they treat each other. That is all part of it.

Meister: You’ve also made digital videos. What interests you about those?

Barney: I have one film called Youth [2016–18] in which I filmed the same identical twin boys, following them year after year. That film is a combination of digital, Super 8, and some stills, even an 8-by-10. When you look at the same subject matter with a different medium, do you feel differently about that subject? That’s what interests me.

Meister: In 1990, seven years after you showed your first picture at MoMA, Catherine Evans did a solo exhibition of your work there. Do you remember how that came about?

Barney: I don’t, but it was pretty unusual. I felt like it was pretty early to give me a show. It was very much the greatest hits of what I had done up to that point. After that, other museums in the United States gave me shows. This all has to do with Janet and her connections because she knew so many people in all those museums: Columbus, Cleveland, Denver. They all bought my work and gave me shows, mostly Theater of Manners work.

Meister: I love capturing what a great dealer can do for an artist’s career.

Barney: This was it, especially at that time. A lot was happening, very, very, quickly.

Meister: Were you there for that MoMA opening?

Barney: Oh yes, I was. I remember getting my hair done and the hairdresser did the worst kind of Toulouse-Lautrec [updo]. I remember Janet’s face when I walked in. When I look at the snapshots, I think, Why didn’t I take it down? Luckily, I was so young and thin and I had a beautiful dress on. But I don’t know why I didn’t just tear it down.

Meister: Let’s jump forward a bit, to your next major body of work. What made you decide to go to the American Academy in Rome?

Barney: That’s very simple: Chuck Close and Dorothea Rockburne. Both said, “Tina, you’ve got to go and apply.” I kept thinking about it but thought it was too crazy. Then, by chance, a friend of mine, who is also from Sun Valley, had an Italian friend who lived in Rome. I met her as she also lived on the East Coast here and traveled back and forth. It was love at first sight. I knew that I had a friend there that was going to help—that woman really was the beginning, the creator. I couldn’t have done The Europeans without her. Bob [Liebreich, Tina’s partner] and I went together and lived at the Academy. We went three different falls [1996, 1997, 1998], but she supplied the friends. What I had not realized is that sometimes Italians marry different nationalities. They would say, “Oh, I have a cousin in this country, I have a nephew in that country,” and that is how it dominoes into other countries.

Meister: Will you talk a little bit about The Europeans?

Barney: As with all my projects, at first I never thought something would come of it. Bob was my assistant. When I got to the first location, it was so beyond anything I could have ever imagined in fifty-thousand million years, I thought, Oh my God. For the picture Father and Sons, it was really like central casting had come in and done a set for me. Every time I met another person, they introduced me to another person, and it would just get better and better. It was eight years of bliss. In some countries, it was more difficult finding people—I don’t speak German, for instance. It makes a big difference to speak the language.

Meister: Do you think that that would have been different if you had been approaching American strangers?

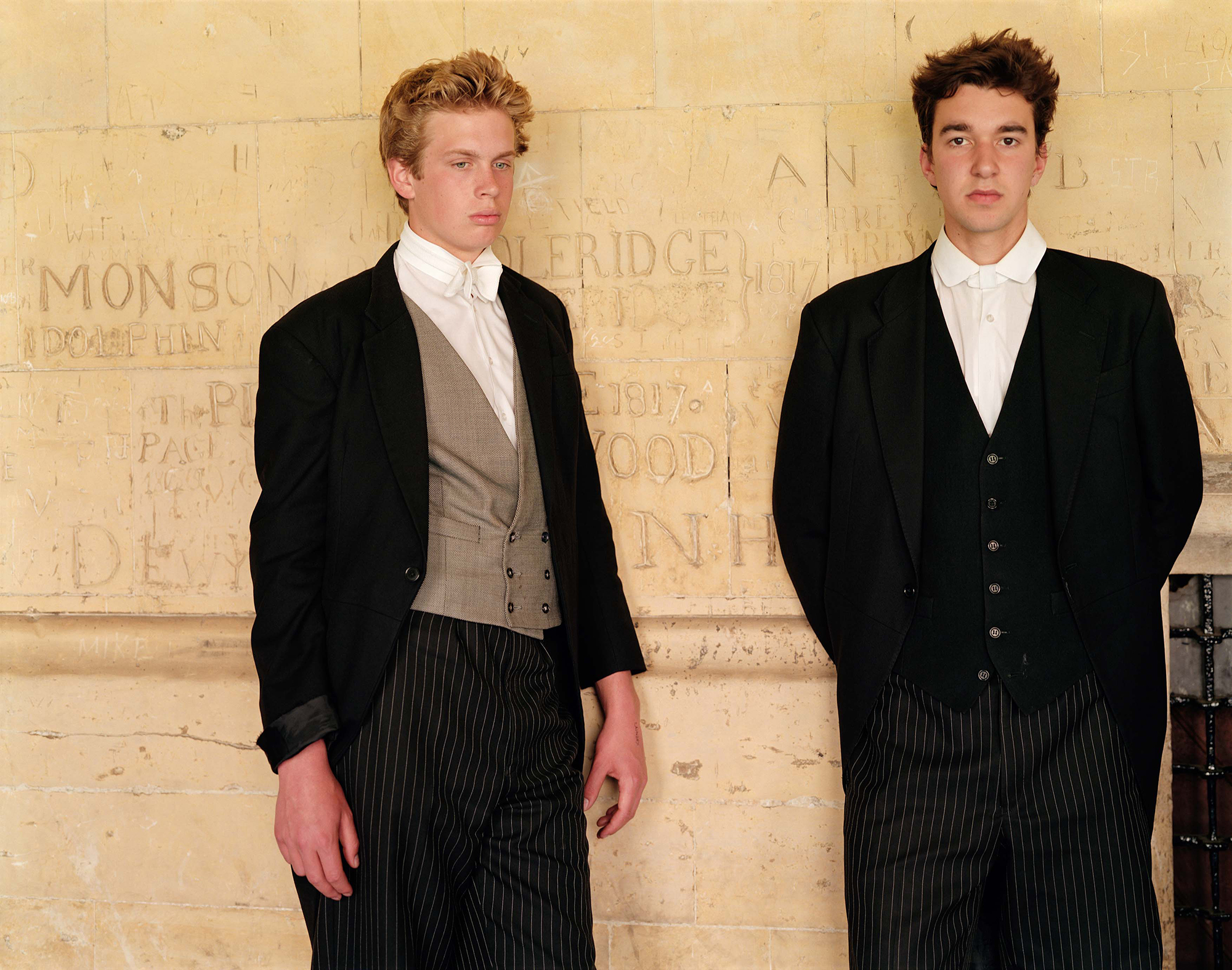

Barney: Gosh, I never thought of that. But, you know, you can’t even compare because quite a few of these people were nobility. Some Americans think they’re nobility but boy, there’s a difference. I’ll tell you what it is. The act of having your portrait made was so much a part of their culture and their heritage that it was a very normal thing for someone to come in and make their portrait without knowing them. The beautiful part—and I noticed this on that first picture—was that I could not direct these people or tell them what to do. Not because of the language, but just because of the way they were. They held poses that I think are subconsciously handed down from generation to generation, for the sake of the portrait. I don’t know if I’m making that up, but I felt it, and right away the pictures became more formal, or static. The resolution was so beautiful, because for once people weren’t moving around, out of the plane of focus. When I started printing, they were better than any picture I’d ever made in the sense of quality of focus and color and eventually lighting—the lighting was just like a joke in the beginning.

Meister: You resist characterizing the subjects of your portraits in your titles, yet you once said, “I know now that before I take a picture, I have to be sure how I feel about the subjects.” Do you still feel this way today?

Barney: That depends so much on the situation. It has to do with whether it’s a job and because I don’t really photograph people I know well anymore. Youth is probably the last time I photographed people I knew well, although not as well as the pictures in Theater of Manners, because they weren’t my children, brothers, or sisters.

Meister: Did photographing The Europeans change the way you would approach that statement?

Barney: Absolutely. That project was so very different. It was people I didn’t know at all. Sometimes I didn’t speak their language. I was in a foreign place, thinking about portraiture in a different way than ever before. Most of the time it was formal or visual in The Europeans.

Meister: To the question of artistic communities, do you feel that you’re a part of one?

Barney: I don’t ever feel like I was part of a photo or art group. I was in Sun Valley because we were all stuck in that little place, but since I came back here [to the East Coast] I’ve really been on my own. Larry Sultan was a really, really good friend. I met him through Janet Borden because we both showed there. We had the most in common of any photographer I’ll ever meet. We just knew that what we were doing was deep down the same thing, and we were tortured by the difficulty of what we were doing. But most of the time, I didn’t really hang out with other photographers.

Meister: What about Mitch Epstein? How did you become friends?

Barney: My friend Judith Freeman said, “You should meet Mitch Epstein,” and I called him up and said, “Let’s meet.” I actually introduced him to his wife, so yes, we’re very good friends. He is the kindest, most generous person you could ever find. Some artists are very protective of what they do in many different ways, and Mitch just isn’t. He’s always the person I call.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Kasmin, New York

Meister: You are not a big self-promoter. You are, dare I say, a little shy. And yet for Theater of Manners, you appear in more than twenty photographs. That was a pretty big chunk of your first book.

Barney: I can’t remember why I thought that was important. You’re right, because that was sort of unlike me. But I think that book had a lot to do with the editor Walter Keller, who kept on saying, “More, more, more.” He was brilliant, absolutely brilliant. I’m so glad I did it.

Meister: You and I got to know each other better through August Sander: you were the first person to speak at the five-year research initiative Noam Elcott and I convened. You set the tone in such an unexpected and moving way because you mused about August Sander as a human, noting that “every word you say, every move you make, reflects on that photograph.” I’d like to ask you to think about August Sander in the context of this exhibition of your portraits.

Barney: I love his work: the purity of it, the simplicity. Really, portraiture is my great love. When I say portraiture, I mean someone just standing there with nothing around, doing nothing, just looking straight into the camera. About as simple a picture as you could take. The complexity of that, the investigation into a human being by using that machine—those two things together, to me, are the ultimate, and the most difficult.

Meister: Hearing this brings to mind some of your self-portraits, where it’s just you and the camera, almost wrestling with one another.

Barney: I think if we look through the history of art, self-portraits are probably the most important works an artist makes. Probably because you know yourself the best. I think photography is the most difficult medium to use to do this. Of course, others that use other mediums would probably say their medium is the most difficult. The camera has the problem of focusing. How do you focus on yourself? Well, there are different tricks, but it’s damn hard to do. Also, what you’re thinking about when you take the picture. To me, that’s probably the most important thing of all, what you decide to think about.

Meister: Because you think you can see that?

Barney: Well, you should be able to. You hope you can. And then can you answer that question yourself, too? Who am I? What am I?

Meister: I’m curious to hear what you think of “environmental” portraits, which I consider an important piece of your oeuvre. I’m surprised to hear you say that somebody without anything around them is the purest form of portraiture.

Barney: That is because it’s the most difficult.

Meister: But it doesn’t seem to me like you’re taking the easy way out with the other ones . . .

Barney: The more stuff in a space or a room for me, the easier it is. The more minimalistic a space is, the more difficult it is, because then you have to work harder. You’ve got to think about that figure and what to do with it.

Meister: I’d like to conclude by asking how you feel about being an artist, despite your not-so-bohemian upbringing?

Barney: I actually really struggle to say that I’m an artist. Well, first of all, I feel like that’s such a phony thing to say. Then again, it’s just so much a part of me that I don’t feel like it’s a separate thing.

This interview originally appeared in Tina Barney: Family Ties (Aperture/Atelier EXB, 2024).