Essays

Inside the New Photography Center Energizing Accra’s Art Scene

Home to a gallery and thousands of books, the Dikan Center is the latest in a growing number of creative hubs across Ghana.

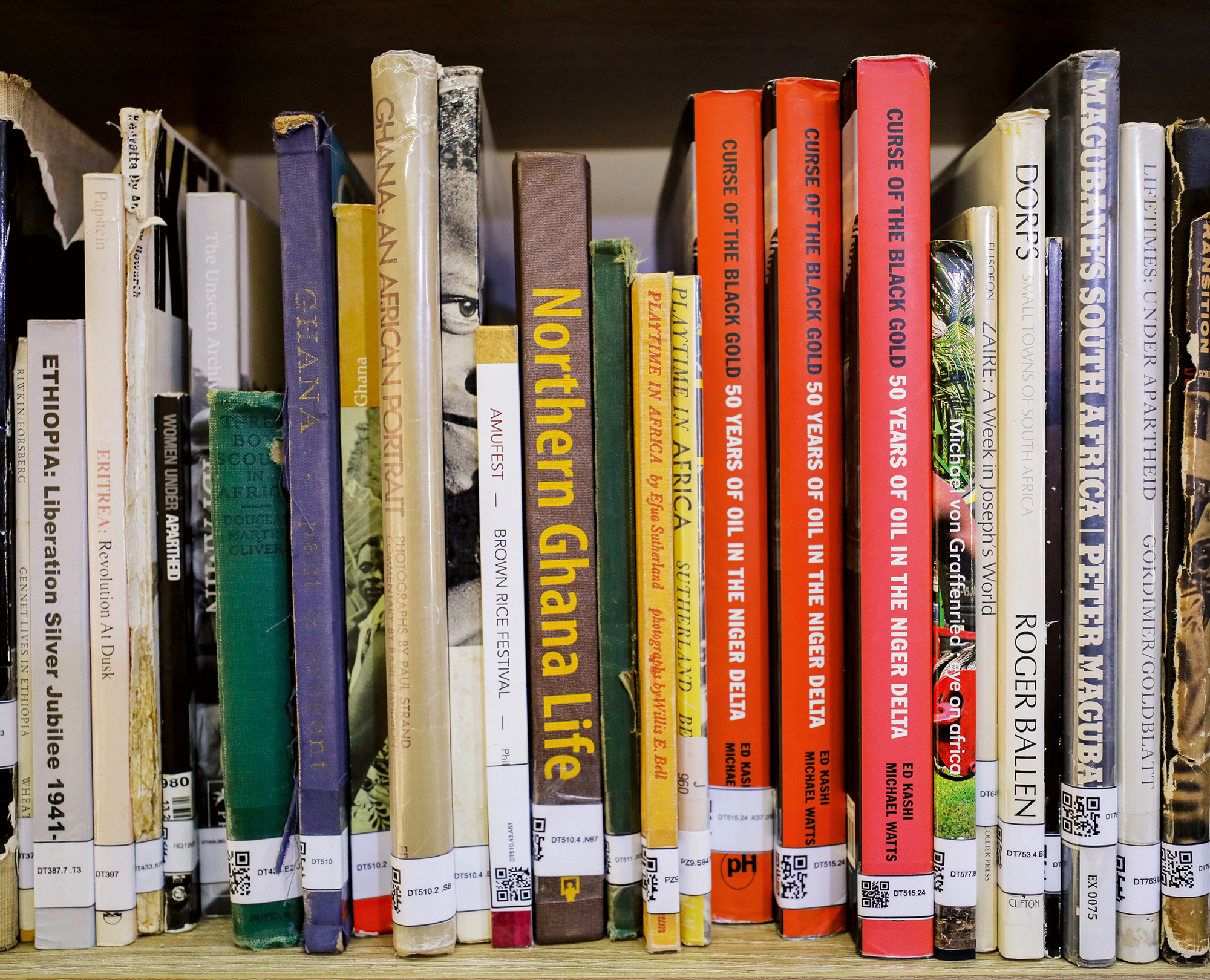

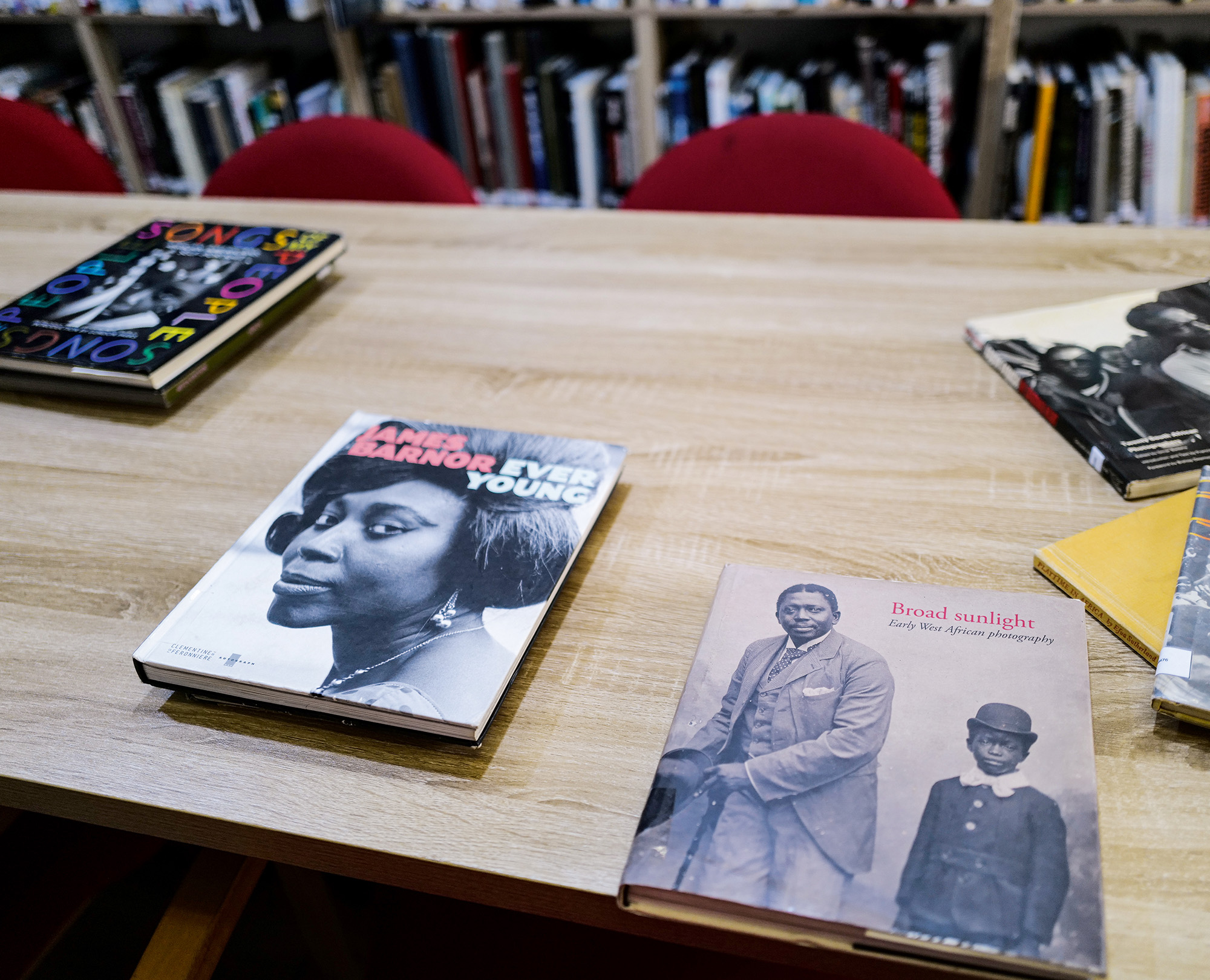

One recent Friday morning, in the library at the Dikan Center, Nana Asomani and his friend and colleague Tiana switched from looking at their computer screens to conversations about some work on which they are collaborating. Both had traveled from different parts of Accra to experience the newly opened photography center. At least once a week, they visit to flip through the thousands of books organized floor to ceiling in the center’s impressive library. It is an oasis in a city as fast-paced and noisy as Accra—not long ago, this institution existed only as an idea.

In the last few years, the cultural scene in Ghana has witnessed enormous growth thanks to initiatives by individuals, collectives, and the government. The contemporary art world has expanded with the emergence of spaces such as the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art; its sister institutions, Red Clay and Nkrumah Voli-ni, in the northern town of Tamale; Artemartis, an Accra-based contemporary art collective and agency; and Accra’s artist-run Compound House Gallery, which supports and promotes contemporary art practices in Ghana. Recently, in December 2022, the internationally known painter Amoako Boafo opened dot.ateliers in Accra. This multipurpose three-story structure, down the road from the Dikan Center, houses a studio, gallery, café, and library, as well as a space for art residencies.

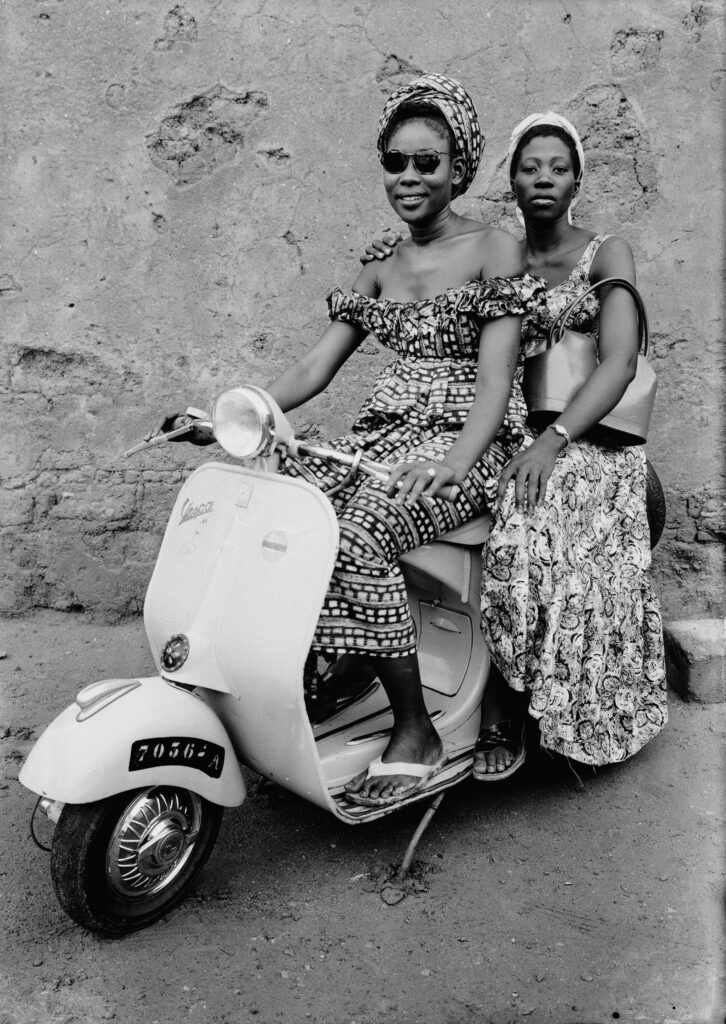

The Ga people of Greater Accra say “loo pii fiteee wonu,” which translates as “too much meat does not spoil the soup.” This idea explains why the creation of the Dikan Center is exciting—the institution adds variety to the growing number of artistic spaces the country’s creative community needs. It expands on existing projects outside of Accra, such as the Nuku Studio’s Center for Photographic Research and Practice, established in 2015 by the photographer Nii Obodai and formally opened in Tamale in 2018. The studio is famous for the Nuku Photo Festival Ghana, which gathers both local and international image makers and visual artists of all levels. A recent photography exhibition there focused on life in northern Ghana and presented a range of photographers.

Dikan means “take the lead,” which is something the center’s founder, Paul Ninson, appears keen to do.

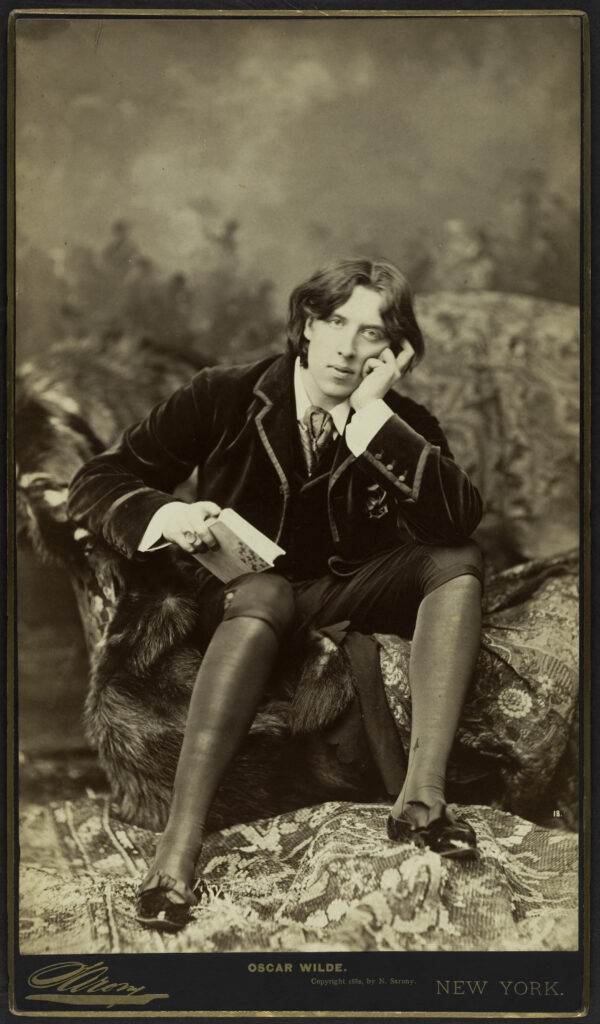

Dikan, an expression from Twi, one of many Ghanaian languages, means “take the lead,” which is something the center’s founder, Paul Ninson, appears keen to do. In 2019, while studying at the school of the International Center of Photography, New York, Ninson decided to set up Dikan. At that time, he was collecting photography books in the United States, an endeavor that grew into a vision of building a photography library in Ghana to share with young people carving their own paths as image makers. The library project, funded via a crowdfunding campaign organized by Brandon Stanton, founder of the popular Instagram account Humans of New York, required the shipping of thousands of books from the United States to Accra. (There are an estimated thirty thousand books owned by the center.)

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

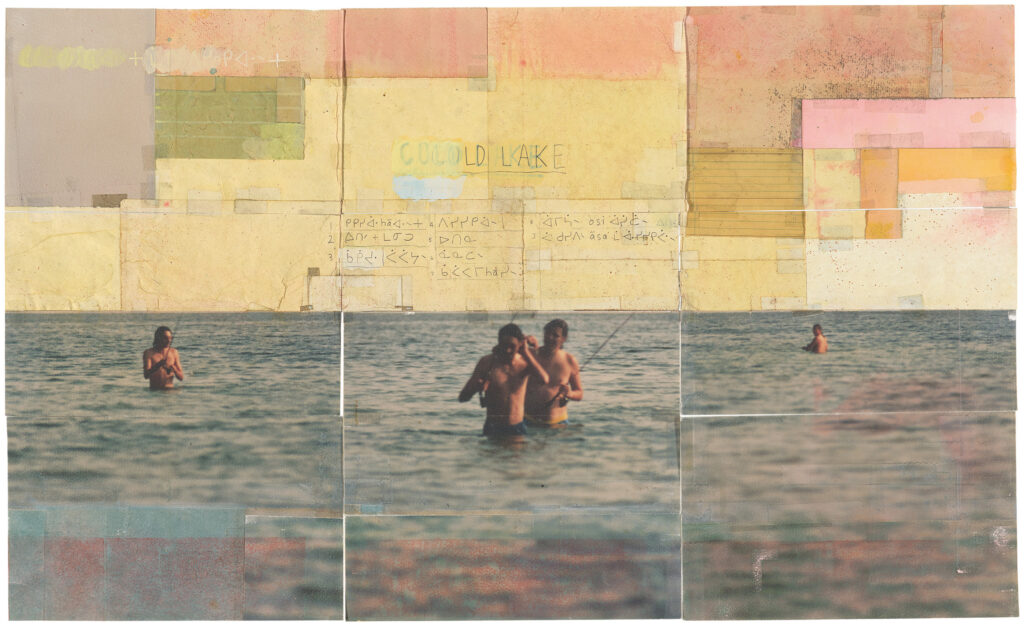

The Dikan Center, which in addition to its library also functions as a studio, a classroom for photography workshops, and an exhibition space, officially opened in December 2022 with Ahennie, a photography exhibition featuring images by Ninson and Emmanuel Bobbie, affectionately known as Bob Pixel. Two months prior, the center soft-launched with Bob Pixel’s first solo exhibition, a retrospective titled Wo Nim Biribi? (Asante Twi for “Do you know something?”), which celebrated the life and work of the affable photographer, who passed away in 2021. Last March, the center opened 1957: Freedom & Justice, an exhibition commemorating sixty-six years of Ghana’s independence from British rule, where visitors heard E. T. Mensah’s “Ghana Freedom” and the famous “At long last, Ghana is free forever” portion of Kwame Nkrumah’s independence declaration speech playing on a loop through the speakers connected to a video piece. On the white walls were framed photographs from the 1957 Independence Day celebrations in different parts of the country.

Photographs by Francis Kokoroko for Aperture

The center’s work seems to just be getting started, and photographers are taking advantage of the opportunities offered for education, exhibitions, and research. There are hardly any places like Dikan in Accra. The photographer Ernest Ankomah imagines that the space, beyond exhibiting work by members of Ghana’s creative community, might someday serve as a repository for his works, “preserving them for future generations to enjoy.” He reckons that as Africa’s biggest photography library, Dikan is a “vital resource to gauge the extent to which the African story has been told.”

Soon, Dikan will host film screenings and social events aimed at gathering the city’s visual-arts community together. The organization will also roll out programs and workshops. The first of them, Women Picturing Africa, a women-only workshop with the photographer Jessica Sarkodie, was held last spring. Ninson hopes that through such collaborations, with artists both in Ghana and beyond, young people can gain a visual education and take charge of telling African stories.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”