Portfolios

James Welling Recasts the Ancient World

In two recent series, the photographer references fragments of antiquity, pulling the past into the present.

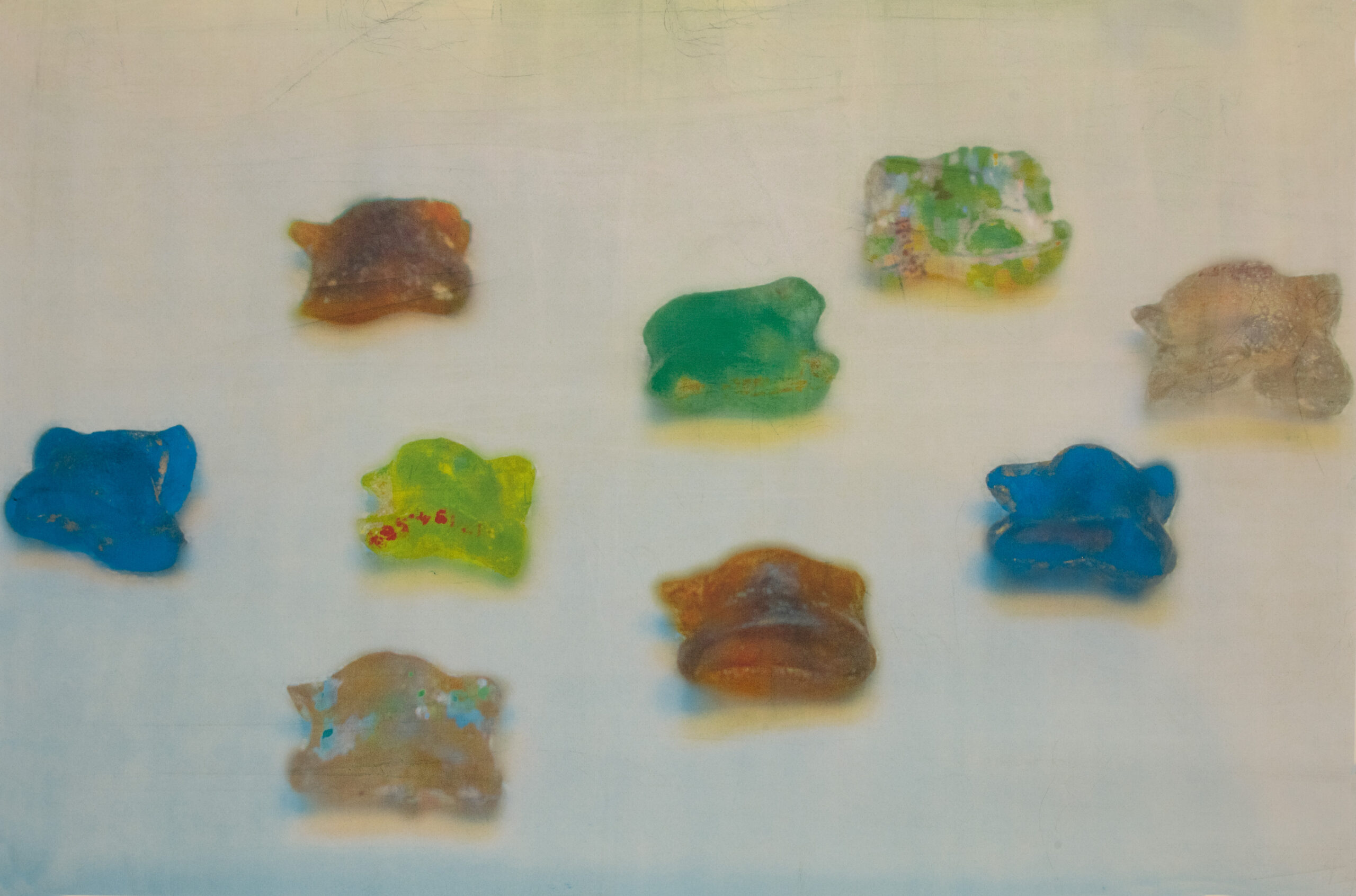

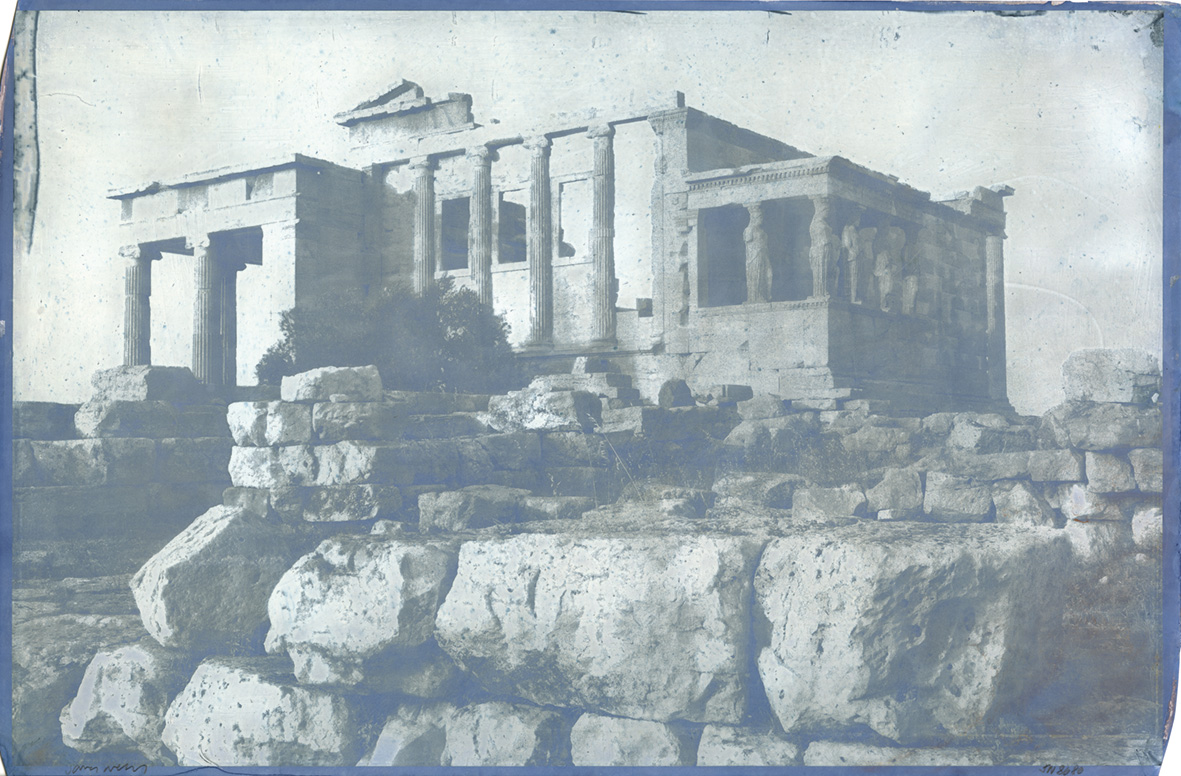

In 2018, the artist James Welling became fascinated with an ancient bust he photographed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that depicted a Roman noblewoman of Syrian origin, Julia Mamaea. The next year, he traveled to Athens and further immersed himself in the architecture, sculpture, and fragmentary remains of the ancient Greek world. Welling photographed extensively, from the facades of temples to small glass game pieces, fragments of tile, and personal adornments. He focused on the gestures and expressiveness of hands carved in stone: a boy holding a luscious bunch of grapes, or Venus demurely covering her nude body.

Much of this work would become the series Cento (2019–21), whose title gestures toward Welling’s method and aims. Typically referring to a work of poetry or music, a cento is made from accumulated fragments of the work of other, earlier artists. Through its form, a cento pulls the past into the present and suggests an inherent curiosity about how those fragments might communicate over time, from one culture and place to another. From Cento, Welling extended his interest in human expressiveness to Personae, works from 2021 to 2022 that begin with sculptural busts of individuals of ancient Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Syrian, and North African origin. Throughout, Welling’s deeply experimental and unique color process incorporates elements of photography, printmaking, digital production, and hand painting.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

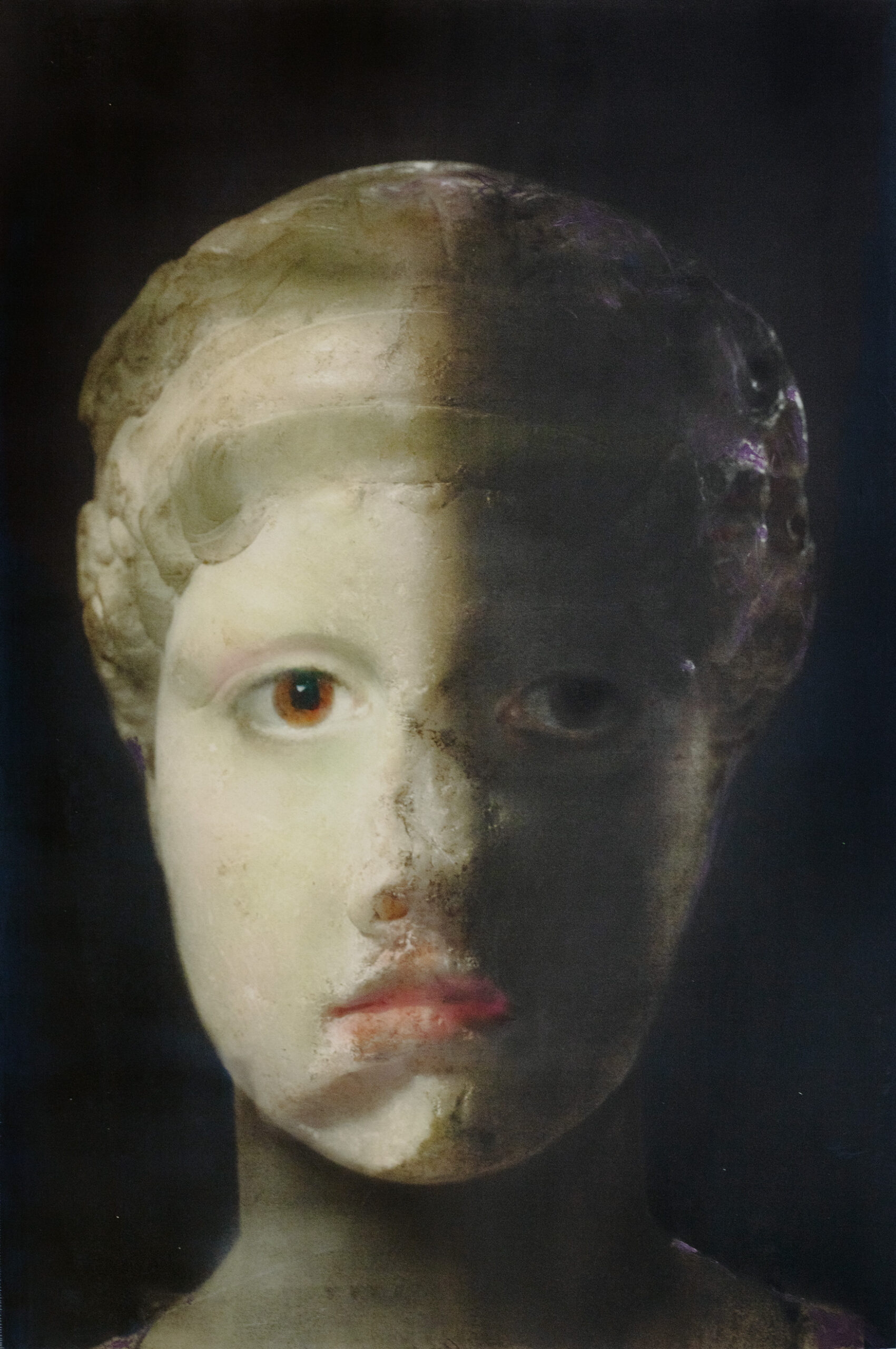

His most recent portraits of busts further the complexity of the cento: Welling began to add new eyes—eyes previously rendered by Renaissance and modern painters and that Welling photographed at museums—to the busts. To this unlikely pairing, Welling adds skin tone, hair color, jewelry, and other responses to the busts’ original hairstyles and fashions, sometimes updating them with contemporary looks. This depth and range of source material manages—seemingly against the odds—to coalesce into an animated moment of recognition, the sense of seeing another human, from another time, conjured before us.

In one such portrait, a young woman looks out from behind the partial veil of a dark shadow cast across her face. Her brown eyes, illuminated with light captured by an unknown painter from an unknown time, show her to be lost in thought. A smudge of warm pink enlivens her lip, the edge of her eye, and a blush on her cheek, and a touch of purple at her shoulder, indicating her dress, carries through highlights in her styled hair. Logically, the image is incongruous, built over time by at least three artists (the sculptor of the bust, the painter of the eyes, and now Welling). But intuitively, it is seamless. As a viewer, I know this mood, this transitory and yet timeless feeling of being lost in thought. Aphrodite has never appeared more relatable, even as she is absorbed in her world, unconcerned with ours.

In the year 2022, there is no shortage of means with which to construct apparently human images, many drawing on the machine learning of artificial intelligence to create unnervingly convincing forms. Faces can be generated endlessly from vast assortments of previously photographed ones, mined from image banks, and scraped from online sources in a feedback loop that easily drains a sense of earlier place, time, and context. Those constructed faces ask something about what it means to be, and to picture, a human. Welling’s images also ask this question, but very differently, with a process that points to their own conclusion about human individuality and its representation. But this conclusion is more of an offer: Welling’s renderings describe not just a world unto themselves but an invitation to connect with those worlds—to recognize them—from the ever-shifting vantage point of this one.

All photographs courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Marian Goodman Gallery, and David Zwirner

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”