Photobooks

Japan’s Unparalleled History of Photography in Print

An expansive new book shows how the magazine format was a major, genre-defining space for Japanese photographers.

Not long ago, Daido Moriyama told me that his favorite way of encountering photographs is in a book or magazine. Nobuyoshi Araki has emphasized that “the photobook—not too big—is still the best way to show photographs.” And Tomoko Sawada has proclaimed that her photobooks are “works of art in their own right.” Indeed, many Japanese photographers understand books, as well as magazine features, as the ideal means of presenting their artistic output, often putting them on par with framed photographs on a wall. The importance of the printed page to Japanese photography cannot be overemphasized.

Over the last twenty years, images by a growing number of Japanese photographers have been shown in exhibitions worldwide. Simultaneously, the international photography community has begun to accept the photobook as a valid form of artistic expression, discovering, in the process, the innovativeness and significance of Japanese publishing. Yet there are still few comprehensive English-language books that consider the history of and specific sociocultural context for Japanese photography. Publications such as the 2003 exhibition catalog The History of Japanese Photography, by Anne Wilkes Tucker, Dana Friis-Hansen, Ryūichi Kaneko, and Joe Takeba, and my own book Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography since 1945 (2018) include select photobooks and periodicals but do not focus on them. The short-lived but influential 1960s journal Provoke was examined in a 2016–17 touring exhibition and related catalog. Even so, the history of Japanese photography magazines has remained largely underexplored.

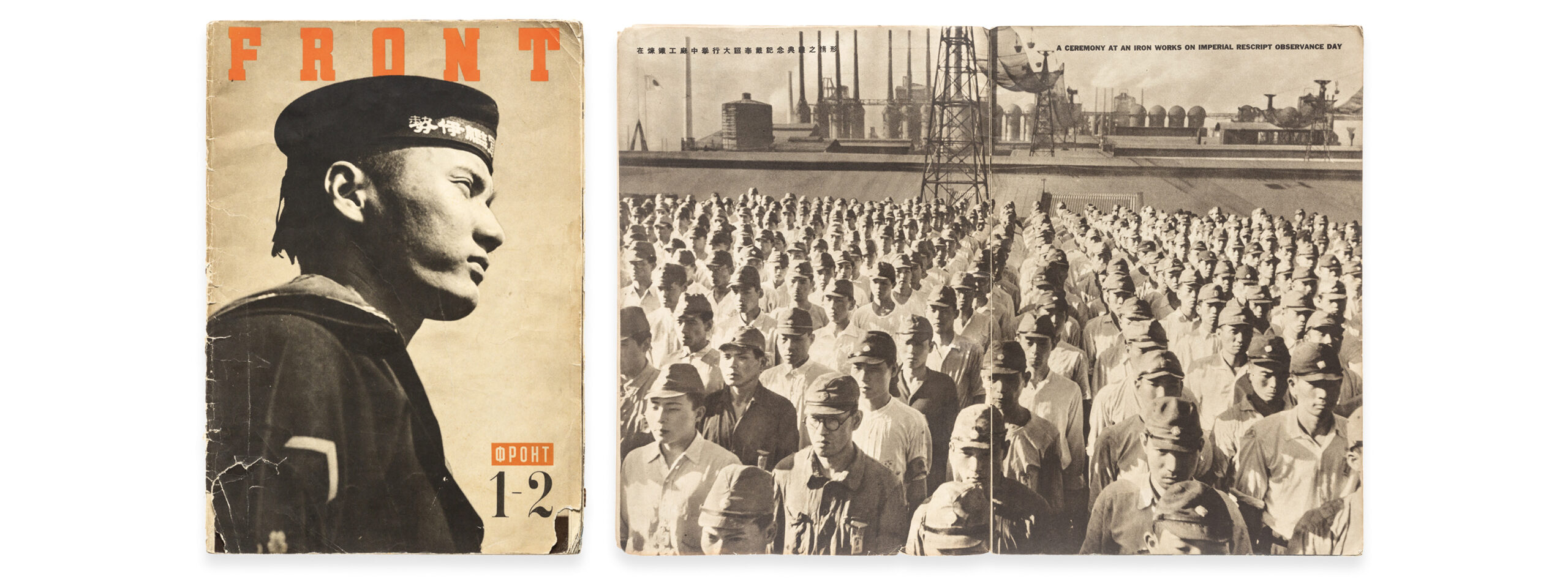

Cover of Front, Volumes 1 and 2, 1942, and spread from Front, Volumes 10 and 11, 1944, with photographs by Ihei Kimura

Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s–1980s (Goliga, 2022; 500 pages, $100), by Ryūichi Kaneko, Masako Toda, and Ivan Vartanian, sets out to change this by investigating one hundred years of photographic history in Japan, told through carefully chosen issues of camera and photography magazines. The book unfolds with an introduction describing the authors’ approach and objectives. As an exhaustive overview is impossible, they aim to convey “one story of Japanese photography through the printed pages of periodicals . . . intentionally avoiding a western-oriented approach to ideas of photography, authorship, reading, and the relationship of images.” It offers readers a chance to “see Japanese magazines within a Japanese context.” Some selection criteria are explained. The stories and features highlight significant moments within the history of Japan and its photography scene, shedding light on the connection between magazines and photobooks as well as the roles of photographers and editors. Nude photographs—apart from those of women who were active participants in the creation of their photographs—were excluded, whereas camera advertisements that provide an indication of how technology developed over the years were deliberately left in. Linguistic and design challenges, such as having Japanese spreads, which are read top to bottom and right to left, reproduced in an English book, are addressed in an honest way, conveying the authors’ awareness of their role in presenting Japanese photographic culture to “Western” readers.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

This comprehensive volume is divided into three parts, eight chapters, and twenty- four thematic subsections in roughly chronological order. Starting with the first camera-related publications of the nineteenth century through to those released at the end of the golden age of Japan’s camera industry in the 1980s, the book immerses the reader in the work of internationally famous photographers, along with figures such as Shōji Ueda and Hiromi Tsuchida, who remain overlooked outside of Japan. The selection makes visible the diversity of Japanese imagery and approaches while also showing how magazines were a male domain that mostly excluded female photographers.

The authors have also compiled photographers’ writings that accompanied their images in the magazines, ranging from the realist master Ihei Kimura’s descriptions of his documentary approach toward photographing farming villages in Akita to an imagined, humorous dialogue, with erotic undertones, between a photographer and his subject by Araki. Often translated into English for the first time, these texts reveal how words were often significant components of the visual layouts.

The book immerses the reader in the work of internationally famous photographers, along with figures such as Shōji Ueda and Hiromi Tsuchida, who remain overlooked outside of Japan.

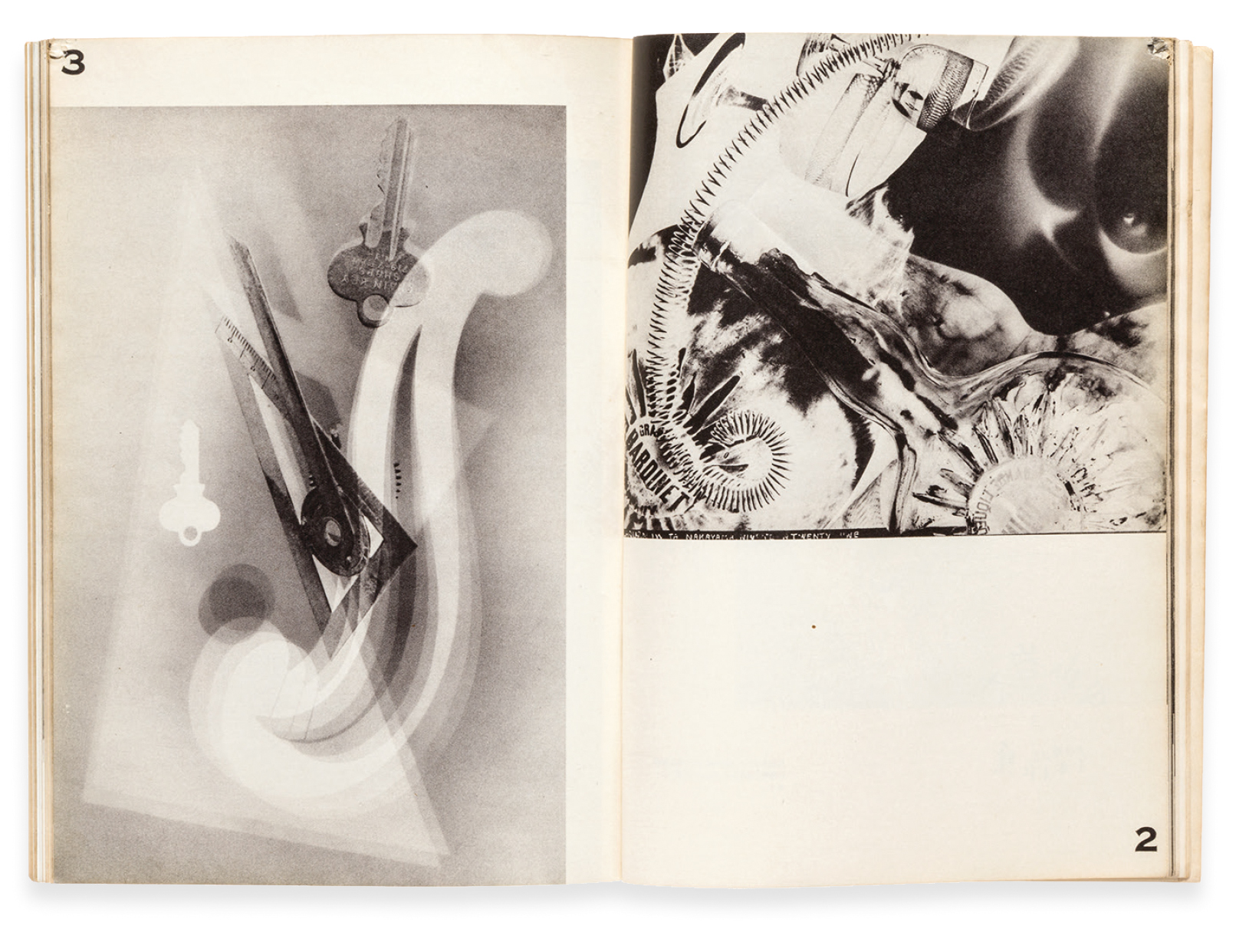

Reproductions from difficult-to-access early magazines that appear in the book are particularly valuable. Hanzai Kagaku, from 1932, features captivating montages that were created collaboratively. An editor provided photographers with a theme: for example, “evoke the atmosphere of the train terminal” using specific motifs, such as a “bustling train platform.” The resulting photographs were published as artistic collages with the editor’s original prompts, creating a fascinating interplay of image and text, of assignment and photographic interpretation. The 1940s war propaganda magazine Front contains striking photographs by Kimura and designs by Hiromu Hara. It is also refreshing to see iconic photographs from the 1960s to 1980s in their original context, including Araki’s first major work, Sacchin, from 1964, Takuma Nakahira’s Fūkei (1970), Masahisa Fukase’s Ravens (1976–82), and Kikuji Kawada’s series Los Caprichos (1972).

All photographs from Ryūichi Kaneko, Masako Toda, and Ivan Vartanian, Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s–1980s (Goliga, 2022)

The idea for Japanese Photography Magazines was born when Kaneko and Vartanian collaborated on an earlier project about 1960s-to-1970s Japanese photobooks. Vartanian realized that “a discussion of photobooks required a considerable understanding of photography magazines, because that culture was the context and system through which the photobooks from Japan were greatly informed.” Japanese Photography Magazines, a seven-year undertaking, is a well-researched, balanced, and sensitively designed book that provides a compelling story and convincingly presents the magazine format as a major, genre-defining space.

Japanese Photography Magazines is also the last major contribution by the legendary Kaneko, whose death in 2021 shocked the Japanese photography community. In addition to being thirty-second in the lineage of monks in charge of the Tokyo Buddhist temple Shogyo-in, he was a pioneering historian, teacher, and curator of Japanese photography, and an avid collector of magazines and books. Without Kaneko’s expertise and collection, this impressive publication would not have taken shape. It will, hopefully, contribute to more in-depth research on overlooked Japanese photographers and Japan’s unparalleled photography culture, beyond the “fetishizing” of vintage prints and photobooks as collectors’ items.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America,” in The PhotoBook Review.