Portfolios

John Chiara Illuminates the World’s Simple Mysteries

Building large-scale camera obscuras, Chiara makes wistful photographs that recall the medium’s origins—and our own.

Some three hundred years ago, the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico came to a humble conclusion that still startles today—that one can understand only what one makes. Perhaps it’s true to say that the claim grows only more astonishing as the centuries accrue and technology evolves at such a breakneck pace that very few, if any of us, make anything for ourselves anymore. The paradox baffles the mind (or does so if we take Vico at his word): in the twenty-first century, when any one of us has in the palm of our hand all the knowledge the world possesses, we are secretly immersed in a new dark age. We know it all, but we understand none of it. The “cloud” memorizes the images we take, a strange archive of experiences we ourselves have lived, edited, and filtered, accessible when we want to remember what it is we’ve lived—a life, or a kind of life. Proof we were there, wherever there is, digitized and stored away and shareable. . . . But I’m haunted by the suspicion that not one image of it all is a thing we’ve made, truly made, ourselves.

It’s a bleak thought, but one that must be confessed, that our own life is something we don’t understand—one that must be addressed, to see an art such as John Chiara makes. Since the age of sixteen, Chiara has maintained a darkroom, a way of developing for himself the images he’s taken, but a process ornate enough that he began to suspect it interfered with the direct experience of vision and memory driving his artistic inquiry.

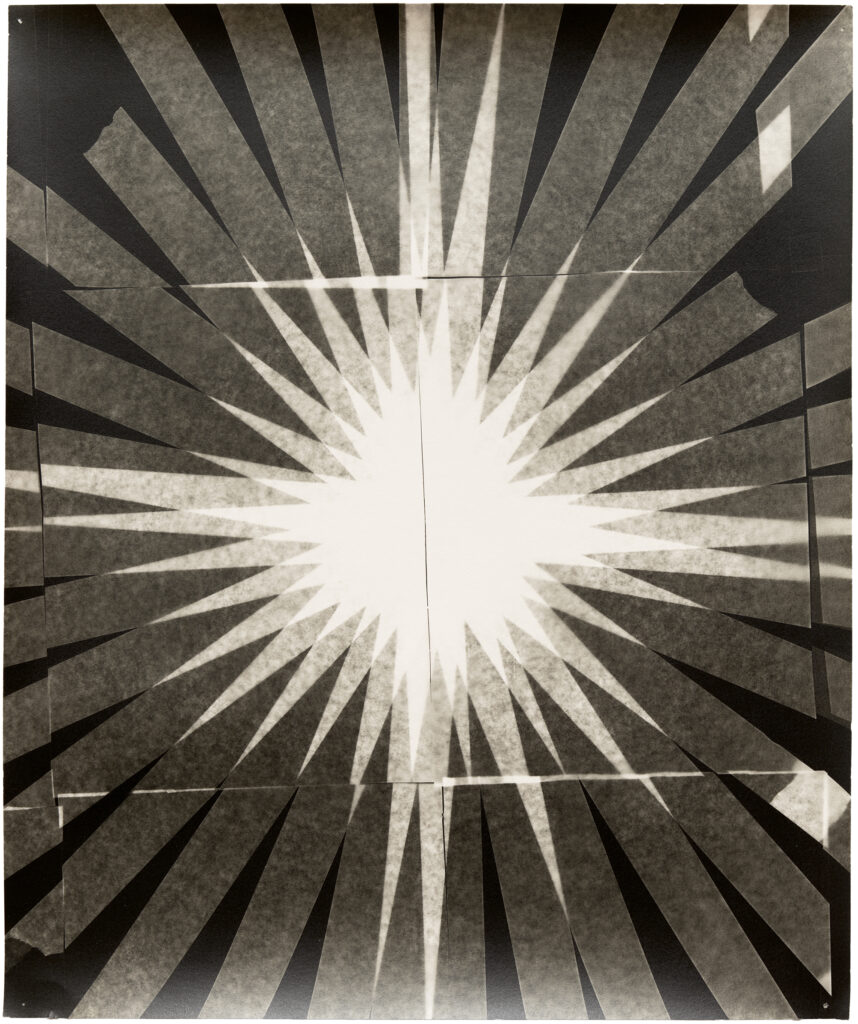

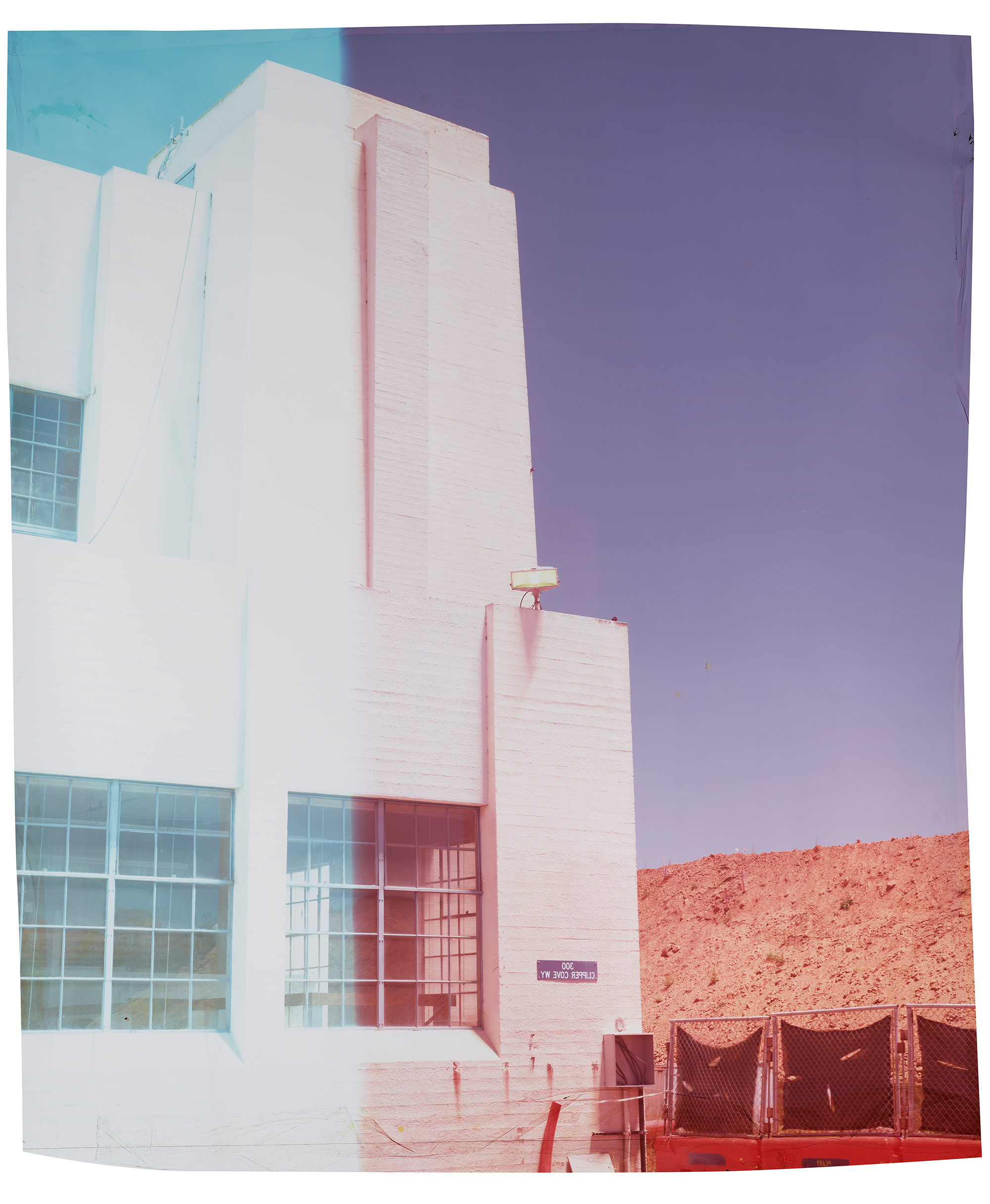

He sought another way, one that is extraordinarily labor-intensive: Chiara builds the cameras he uses, and they’re large. Imagine a Hasselblad box magnified to the size of a small house, towed on a trailer behind a truck and in which the photosensitive paper on which the image is made is put in the camera by stepping inside the camera itself. These cameras reach back through time to the beginnings of the art form itself, the camera obscura, light inverted through a lens and the upside-down image cast back onto the paper for hours. The handmade camera invites in leaks of light and breeze as an inherent part of a process that seeks anything but to be merely in control.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Not simply a framer of a scene, Chiara is an experimenter in time, calling into question vision’s instantaneousness, showing us the eye entangled with light by which it sees, light that the photograph puts on miraculous delay—a delay that feels to me nearly philosophic, almost metaphysical, attuning us to awe and error, making seeing itself something we can no longer take for granted, a reinitiation into the mystery in which we live the hours of our wakeful lives. In photographs larger than our own bodies, a perspective that quietly quickens the child within us, is that fear and marvel of feeling how small one is in relation to all that’s in the world, a fact the adult too easily forgets.

A gift initiated Chiara into his work, a camera his father gave him when he was eight years old—a Nikon the family couldn’t really afford. Rather than promoting a separation from the world, the camera became for Chiara a tool of intimate entanglement with it, as if the lens with its auto shutter taught the child the nature of his own eye. Chiara goes back to those earliest photographs, “the ones of birds far distant in trees or cats rolling on garden hoses and close-ups of grass,” and feels a worthy pride. His work has taken him across the nation and abroad, from his native California, where his love for his art first was fostered, to a recent residency in Georgia.

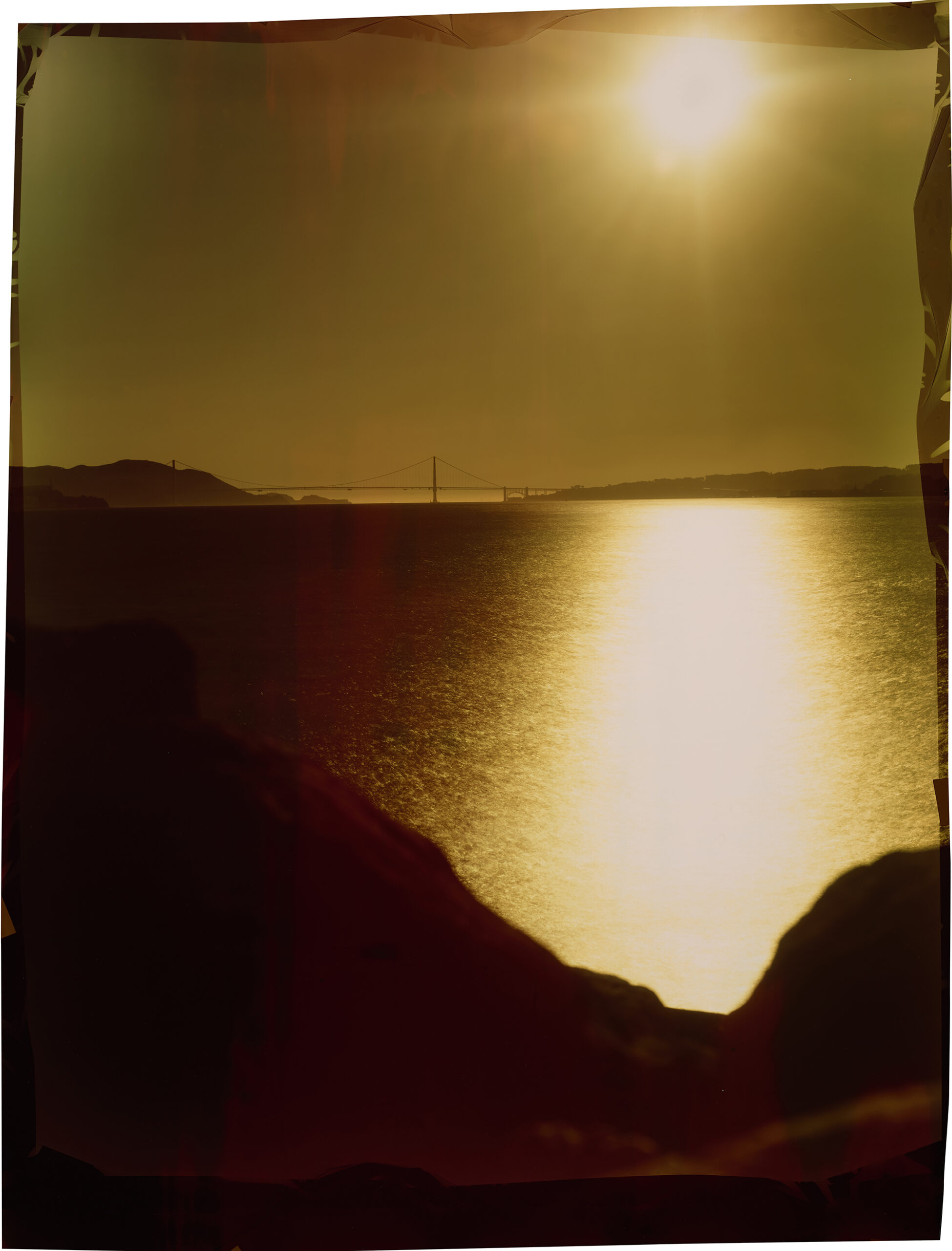

But it’s Northern California, where he trained his eye to see the world around him, that continues to exert a touchstone fascination, as if he hasn’t yet seen what he means most to see. I find myself returning to the series Treasure Island (2020–24), sepia in tone but more golden, full of ancient honey, of the bay and San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge. The sun’s light tunnels through the water. The water gleams with a gathered glow the foreground stones of the shore can’t claim. And in haunted silhouette, the cityscape and the lacework bridge, temporary witness to a process of light and substance that has existed as long as light and substance themselves have existed, and will outlast any witness to them. This series focuses on Treasure Island, a landmass as handmade, in a certain sense, as Chiara’s cameras, and sharing their exceptional scale. Built from 1936 to 1937 to host the Golden Gate International Exposition, Treasure Island has gone from world’s fair site to World War II naval base to residential, shifting from monthly rentals to million-dollar condos. What shade is there is cast by nonnative trees: palms, eucalyptus, Italian cypress. It’s a strange thing—how place teaches us how to see.

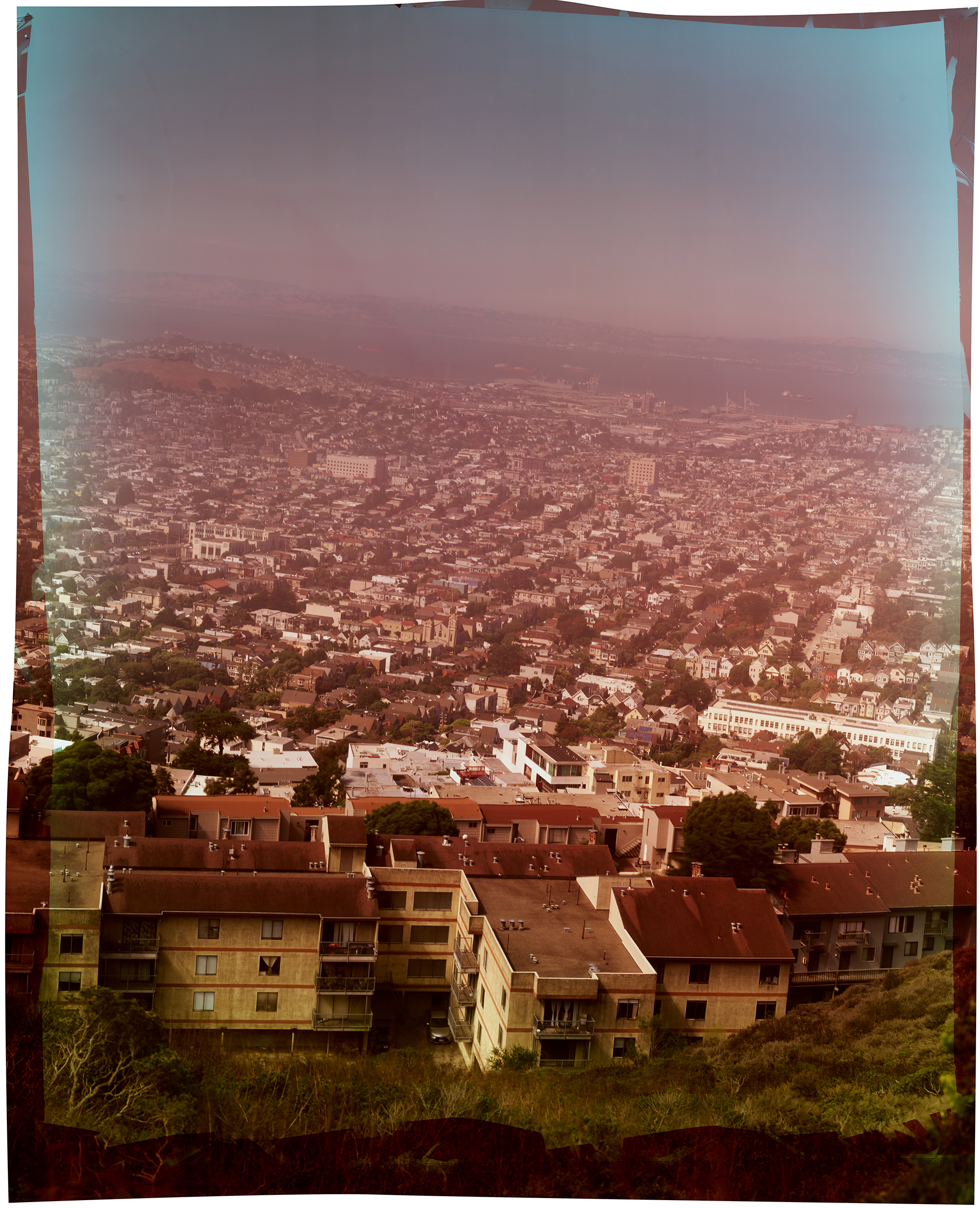

Chiara teaches us to see through the handmade humility that returns to the world its proper wonder. He attunes us to the made-ness of made things—the chromed phantasmagoric spectacle of the metal stands that hold the ropes that mark the lines we wait in; a mooring block of concrete; homes and buildings and the wires and poles that send the electricity that lights the lights within them. Chiara also enlivens us toward the facts of all it is we can’t make ourselves: sunlight, water, land; eyes, mind, life. It puts in my heart a feeling I want to call azure—which doesn’t assure, but describes some instant of the evening sky. Or is it the early morning sky? Either way, Chiara has given us a craft to navigate the terrain: a way of making, and a making that transports us through.

Courtesy the artist

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”