Interviews

Reagan Louie on Surviving the American Dream

The photographer once believed that he had to turn his back on his Chinese culture. Today, his images show what it means to embrace authenticity.

In the 1970s Reagan Louie moved to San Francisco to take a teaching job. The city still had a countercultural flair, and Louie, who at the time considered himself something of a rebel, began documenting the streets and vibrant businesses of its Chinatown. He later traveled to China, connecting to his family’s history and capturing the country’s rapid pace of change. By now, he has spent more than fifty years exploring issues of migration, cultural transformation, and intergenerational dialogue through photography.

As the son of immigrant parents, Louie’s decision to take an art path was a bold one. He studied with such major figures as Robert Heinecken and Walker Evans, and considers Chauncey Hare, the photographer-activist who famously abandoned the art world to focus on the plight of workers, a mentor, even though technically Hare was Louie’s own student. Louie also often felt estranged from the art world. After graduate school at Yale, he almost gave up on art, taking odd jobs digging sewers before pushing himself to return to photography so that he could pursue his original “intent to understand and discover the world.”

In 2022, Louie’s work was included in one of three inaugural exhibitions related to the Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI) at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, an ongoing initiative dedicated to the study of Asian American art. Here, Louie speaks with Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, codirector of AAAI, about his artistic journey and the stakes today for Asian American visibility.

Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander: Let’s talk about this particular moment we’re in, which is both difficult and celebratory for Asian Americans.

Reagan Louie: Yes. Our talk is taking place at the beginning of the Lunar New Year and a few days after two mass shootings by Asian American men. For me, it represents the kind of ultimate American assimilation—these two men shot and killed as Americans, not as Asians. The tragedy illustrates a lot of things that I felt. They were unseen and isolated. That reveals to me this irony of the promise of the American dream, which can never be fully realized by people of color. They can never become white. For Asians, that foreclosure is double, because we’re still perceived as being quite exotic and inscrutable, and, therefore, forever alien.

This is, I think, what my work is about—being both Asian and American. It’s kind of like a Venn diagram, where the Asian circle and the American circle overlap. That union between the two circles of identity is what matters. Perseverance is the hallmark of my life, a quality I share with all Asian American artists, if not all artists. I’m not really sure where it comes from. But surely it has to do with survival, this profound need we have, or I have as an artist, and the success, if I’ve had any successes—I’ve had some—has been accompanied by many moments of feeling unseen and marginalized. In fact, I first believed that I had to turn my back on my Chinese culture to achieve the American dream, to be successful.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Alexander: You’re reflecting on your more than fifty-year-long career from a certain vantage point. In the early phases of your career, how much do you feel these factors of identity, both from your position as an Asian American and from how you and your work were seen, impacted the way that you moved through school or the art world? I’m thinking, of course, of your early experiences with Robert Heinecken and, later, Walker Evans, both of whom you studied with. To what extent did these questions come up then for you?

Louie: Almost never. Because at that time, it was all about formalism, and any other conversation was irrelevant. In the 1970s, there was no interest, like there is now, in any of the other questions, particularly around identity. There was always this struggle going on between my Asian side, which was almost the opposite sometimes of American behavior and values, which had privilege over your Eastern ideas or values or culture. You had to be extroverted, boisterous in America, not stoic. Hubris always triumphs over humility, and individualism over the collective. So these were all dynamics that were internal in the work I did.

Until college, I was a pretty indifferent student. I wasn’t your typical model Asian American student. I nearly flunked all my math and science classes. But somehow, in my first year, I took an art class as a gut course. But I was enchanted. It opened me up to new ways of looking and being and understanding the world, a new way of communicating, and I developed a curiosity that has remained to this day. This was a moment when the world was changing. I’m a child of the 1960s, and there was a bit of a rebel in me. I was seeking truth and light and beauty and all that. I was a romantic. I still am in a lot of ways.

This fusion in using the camera to find my Chinese, non-Western self comes with many obstacles, including adopting its logic and its values.

Alexander: That also makes me think about going back even further into your life—your mother and your father, and their roots, and how you came to be.

Louie: There was no precedent for becoming an artist. Growing up, I recall going to a museum only once. My family didn’t have time or interest in cultural matters, really. They were too busy making a living, like most people in that generation. So when I decided to become an artist, and not become a lawyer or a doctor, or at least a pharmacist, and studied art instead, I really knew deep down I had to abandon my family for the moment. Abandon those obligations, familial obligations of being the oldest son, and all those expectations that come along with it. I had to turn away from my Chinese self. I mean, literally, physically. I just didn’t see them for a while.

I chose this tool, photography, which is the quintessential Western invention, a paradox that both estranged me from my Chinese self and my family but also gave me a way back to discover and to integrate those two selves. This fusion in using the camera to find my Chinese, non-Western self comes with many obstacles, including adopting its logic and its values, the machine logic, which you kind of resist.

There’s a critical divide that needs to be recognized, or reckoned: immigration to America before 1965, and after. I’m a boomer. My generation’s experiences are more connected to that first wave of Chinese immigration that began in the nineteenth century. But I’m somewhere in the middle if we consider that the Chinese American experience is a continuum from the 1800s until now. My father was born in China. Even though I’m fourth generation on my mother’s side, which is very unusual, I identify as a second-generation citizen because my mother’s family really grew up in isolation, away from the surrounding communities. My first language is Cantonese. We lived in a pretty enclosed world. Both waves of Chinese immigrants came for the same reasons—for a better life for their families, for themselves. But we faced very different kinds of receptions. The pre-1965 immigrants faced open hostilities, physical violence, whereas the post-1965 generation was welcomed, albeit with more subtle forms of racism and suspicion.

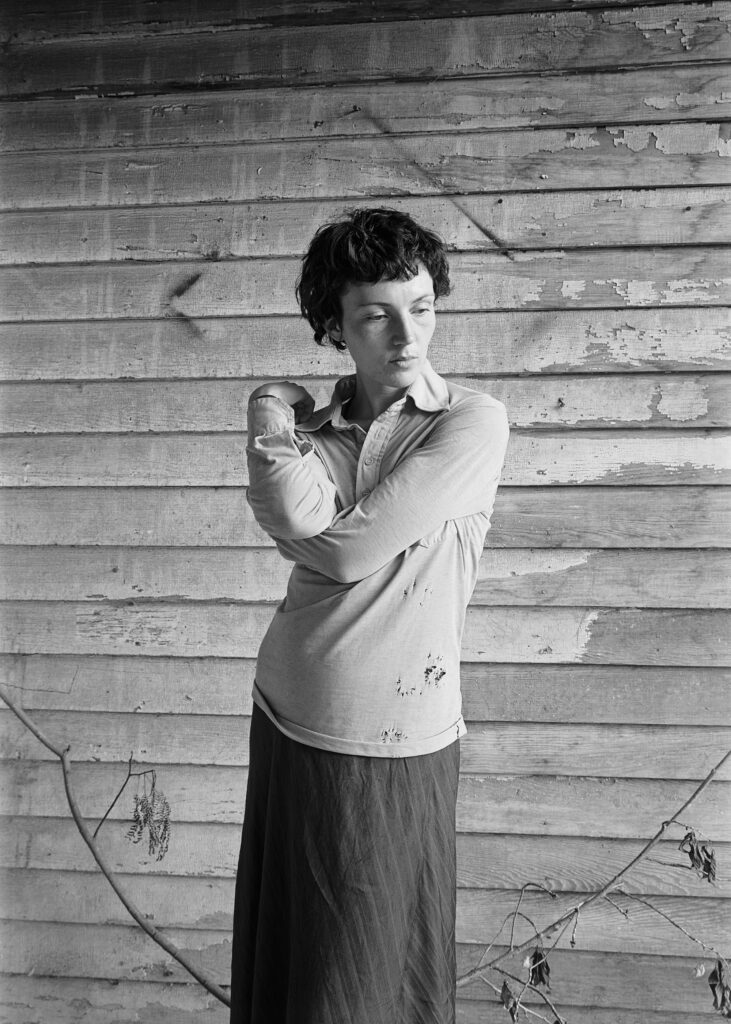

Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Golden Dragon Restaurant, 1979

Alexander: We see that continuing through today, especially during the pandemic. So, in order to pursue photography, you essentially had to turn away from your family. But then, it comes back around that your work is, in many respects, largely about your family—and family in general. I wonder if you might share a little about that process, from arriving at your subject matter in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the earlier part of your career to how you ended up in China.

Louie: There was no way I could explain, even to myself, why I wanted to be an artist—and especially to my family. They took comfort that I went to good schools, and then later on, I became a professor—so that’s how they saw me. Art? They just couldn’t figure it out.

It was only when I came with my father to China in 1981, into his village that he had left when he was nine years old, that my photography made sense to them. That’s when the circle closed, and I really understood for the first time what my work meant to me, what I was trying to do. Eventually, I reconnected with my family.

I moved to San Francisco to accept a teaching job at the San Francisco Art Institute in the 1970s. San Francisco was a beautiful place then. It was still basking in the afterglow of the ’60s. I began photographing in San Francisco’s Chinatown really out of convenience. I lived there, and it looked exotic. I lived around the outskirts, the border of Chinatown and North Beach, in this alleyway called Fresno Alley. Its claim to fame was that my building was the location of a Woody Allen film. It was still really boho life there. You saw the North Beach poets still wandering around, trying to channel Ginsberg.

While I began photographing there out of convenience, it was also a place of my ancestors and memories. Many of my family members, including my grandfather and father, lived and worked in Chinatown initially. I deployed a nineteenth-century stand camera, 4-by-5. I wanted to contrast the incredible detail that camera renders with the motion blurs of people’s movements. I saw them as my ancestors, as ghosts.

Chinatown led to China. In 1980, I answered an ad in a Chinese newspaper to study in China. That’s when I began my forty-year odyssey. Unbeknownst to me, what I was doing was attempting to find another way, a truer life. Again, finding your cultural roots, or even thinking about that as a source for your art, wasn’t heard of then in high-art circles. That was taboo, really. I thought that’s what I was doing, but I didn’t tell myself that was the goal. In fact, I said the opposite: I was taking my educated eyes to picture this new exotic world. I couldn’t really acknowledge the real reason for going to China, my need for some kind of authenticity.

Alexander: Why do you think it is that it took both you and your father going to China for him to understand your practice more fully?

Louie: It was less what we spoke about than our actions. Toisanese especially, and my family in particular, are very laconic. My dad, me, my son, we’re all men of few words. So what spoke to me was watching him become a nine-year-old again. He had tears in his eyes most of the time. I saw his gentleness, which I had never seen, because to survive as an Asian male at that time, when I was growing up (and still, maybe), you had to be a tough guy.

With the two eras of Chinese immigrants, the work that’s produced by the artists of those eras really manifests their time, the conditions they faced. The art made in internment camps, photographically—like the pictures made by Toyo Miyatake—is a declaration that they were here. Right? They weren’t going away. I feel really strongly about that. Whereas the work being made now, which is wonderful and celebratory, it’s about living life out loud.

Alexander: Why do you think it was difficult for you to acknowledge that the need for authenticity was a primary driving force for you to go back to China?

Louie: Again, I drank the Kool-Aid. It was all about formalism and nothing else.

Alexander: Many of the early Chinese immigrants to the United States came from a specific province, Guangdong. This is to say, there are many distinct provinces in China with their own dialects, mores, and histories. Yet here, sometimes, there’s a tendency to view China, this massive country, as a kind of monolith.

Louie: Before I began working in China, I vaguely knew that China was vast and diverse, filled with different dialects and cultural practices. But I didn’t realize to what extent until I got there. I really detest anything pan-Asian right now. I don’t even like the word Asian American.

Alexander: Speaking of the term Asian American, we got to know each other through the Asian American Art Initiative, a project I codirect. Your work was included last year in the exhibition At Home/On Stage: Asian American Representation in Photography and Film, curated by my colleague Maggie Dethloff at the Cantor. I recall that you wrote beautifully in a private note to Maggie and me about what it means to be included in an exhibition like that, even when you don’t love the term Asian American.

Louie: I was struck by how much art in the exhibition came from suffering pain and grief, which I could identify with. We know the pain and suffering caused by internment, or the history of violence directed at Asian Americans, which continues to this day. But equally important for me was the daily pushing against grief and loss that we face, that’s faced by every Asian American every day—racism and discrimination, not being fully seen, just those daily microaggressions against people of color. But in the exhibition, we see Asian American artists pushing back against all that discrimination and hate; from their pain and hardship they made tremendous meaning. Art that gave them solace. Which is why all the work for me is filled with healing joy. It was never bitter. The art in the show reminded us that beauty and grace can arise from pain and loss. It’s that irrepressible human spirit.

Alexander: Recently there’s been a lot of critique of the racially specific exhibition model. From your perspective, working all these decades both within and on the perimeter of the art world, what’s your thought on this kind of model of inclusion in the museum space?

Louie: Super complicated question. I refuse to do this, to perform our Asian-ness. Right? I think it’s great that museums and institutions are recognizing that we’re coming from a different place than just formalism. But I am skeptical sometimes about putting in one or two pictures of an Asian American artist, or whatever. How much difference does that really make? Is it really transformative? I’ve seen too many instances where it’s not. In fact, it’s reductive. It diminishes the work of that artist, seen in that context. If you truly want to make a statement, you’ve got to make the big move. Turn the entire museum inside out. Not just one or two pictures but an entire show. That’s what’s going to pull in new audiences.

Maybe this is a good moment to give you an example of an experience I had with all this in the ’70s. I was a photographer during the very beginning of photography as a fine art. At the top was MoMA, in New York. The museum had a generous portfolio-review policy. The drill was you’d drop off your portfolio and return to pick up the work a few days later. The first time I dropped off the work, it was a tray of color slides I’d made while I was in California that year after I’d returned. They were of places around Sacramento, where I grew up, and they were very formal, beautiful pictures—and I was surprised when I was invited to come in and speak with the curators. They thought the pictures had a sweet quality and asked me to keep them updated. But the reception for my work made in China was much chillier. I couldn’t articulate what it meant.

I’m embracing values that I once rejected. Inclusion, not exclusion. Authenticity, not artificiality.

As I’ve talked about, I didn’t know why I had gone back to China. And there were awkward silences with the curator when the conversation veered away from formal aesthetic issues. At one point, I remember I was trying to talk about my feelings, to try to communicate what was at stake for me. The curator was dismissive. He said he didn’t care about my feelings, only his. It just shut down that conversation. I was really pondering whether I had what it took to be an artist. I was really dejected after that encounter. I tried to step away from art and tried to quit. I applied to business school. I was convinced I didn’t measure up. And I was also tired of always being in debt.

Fortunately, no business school accepted me. But I didn’t know what else to do. Art was the only thing I knew. So, I rolled the dice again. I went into more debt and moved to Beijing, a decision that wreaked havoc on my marriage. I photographed with crazy, wild abandon. Every day, I would wake up as early as I could and stay out as late as I could, taking as many pictures as I could. I shot over three thousand rolls of film that year, 1987. I tried to find aspects of my Chinese self in them, especially the men. I was unknowingly trying to find my Chinese soul that could coexist with my American self. That year something had shifted. I really felt I had broken new ground.

I returned to MoMA with my portfolio, having no expectations. This time, it was even worse—the receptionist just returned the portfolio with no comment. But then, one of the curators at MoMA left a message that said, “We returned your portfolio by mistake. Could you please come back tomorrow with the portfolio?” Which led to, the following year, in 1988, the show at MoMA—New Photography 4: Patrick Faigenbaum, Reagan Louie, and Michael Schmidt.

Reagan Louie, Olympic Park, Beijing, 2008

All photographs courtesy the artist

Alexander: So, in the end, the result was positive. But it still gives me tremendous unease, as I’m sure it gives you—this unstable and unproductive ground of constantly thinking about or relying on forms of validation from predominantly white institutions. And yet, we want to forge careers in the arts. What do we do? What should we do to not be beholden to these types of external forms of validation when that is the most obvious path to mainstream success?

Louie: We have to take nonobvious paths. We’re in a much better place than when I was coming up. Back then, there was so much power concentrated in one institution, almost in one person. It kind of was mimicking, maybe, the time of Abstract Expressionism, when you had Clement Greenberg or Harold Rosenberg creating a school of painting.

Alexander: When we first came into contact, I know you were at a difficult moment in your life, and you were feeling like that was the end of your artistic career, essentially. And yet, here you are in a moment when there has been increased interest in your work. What does it mean for you to step into that reception rather than recede from it?

Louie: It’s been a struggle. I’ve found new allies, new communities. It really pulled me back from the brink. When we first met, I was just realizing the price I had paid, the price we have to pay to succeed in this country, to be a Chinese American. I was in a very dark void. I really thought I was finished and would disappear. But now, I’m embracing values that I once rejected. Inclusion, not exclusion. Authenticity, not artificiality. Heart values, not head values. And joy, not suffering. I’m not fully there yet. But I can see that these are options. And I’m trying to get back to work.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”