Essays

Richard Misrach on the Eerie Grandeur of Global Trade

Rebecca Solnit considers the photographer’s recent work tracing histories of shipping routes and their impact on the natural environment.

Phenomena that appear blue at one time will at others look orange or golden or gray or black as light and weather shift, because color is not inherent in land or water or sky, but an interaction between light and surface, because change is the one constant, because there is a rhythm of light that, like the tides, comes and goes daily. Ships that appear on the water may themselves be coming or going, may be carrying products for import or export, may belong to global conglomerates or oil corporations, may have been on the open ocean for weeks before they came into the San Francisco Bay. Some are fossil fuel tankers, more are cargo ships. The word cargo, meaning burden or load, was itself exported from Spanish to English in the seventeenth century.

Cargo as in burden, horizon as in horizontal. This is a place divided by the horizon line between water and sky, a world drawn together by the enchantments of light, a world of moods made by time of day and weather, by clouds and sun and wind and fog, a world that if you ignore the ships is primordial, sublime, spacious, serene on clear days, other days battered by wind or smothered in fog or dull with smog that gives the sky brown edges. Or maybe two horizons of sorts, two horizontals, waterline and skyline. Horizon as the meeting place of water and air, or sky and earth, lends a kind of stability in a landscape—seascape—skyscape—made of the eternal instability of the cycles of light and darkness, seasons, tides, weather, and human histories.

But the ships are not easy to ignore. Sometimes, they appear as a kind of transgression against the aesthetic grandeur, a disturbance in the space, an industrialization of what still seems natural. At other times, in their monumental size, the way their hulls catch the light, their own lights in the gloaming, they are beautiful themselves. They are reminders that the world comes into this bay again and again as commerce, the way it came in as military might in the decades when the Bay Area’s ports and bases were strongholds meant to defend the West Coast against invaders who never came1, or to launch troops and armadas into the Pacific theater of war. They are easy to see, but it’s less easy to perceive the immense environmental harm of the shipping industry, of mass consumption, of the fossil fuel that fills the hulls of the tankers come to load and unload the foul stuff on which our world runs. These ships carry specific burdens, but they also transport the burden of the industrial age’s consumption and production and its impacts. They carry a burden, a cargo, of meanings.

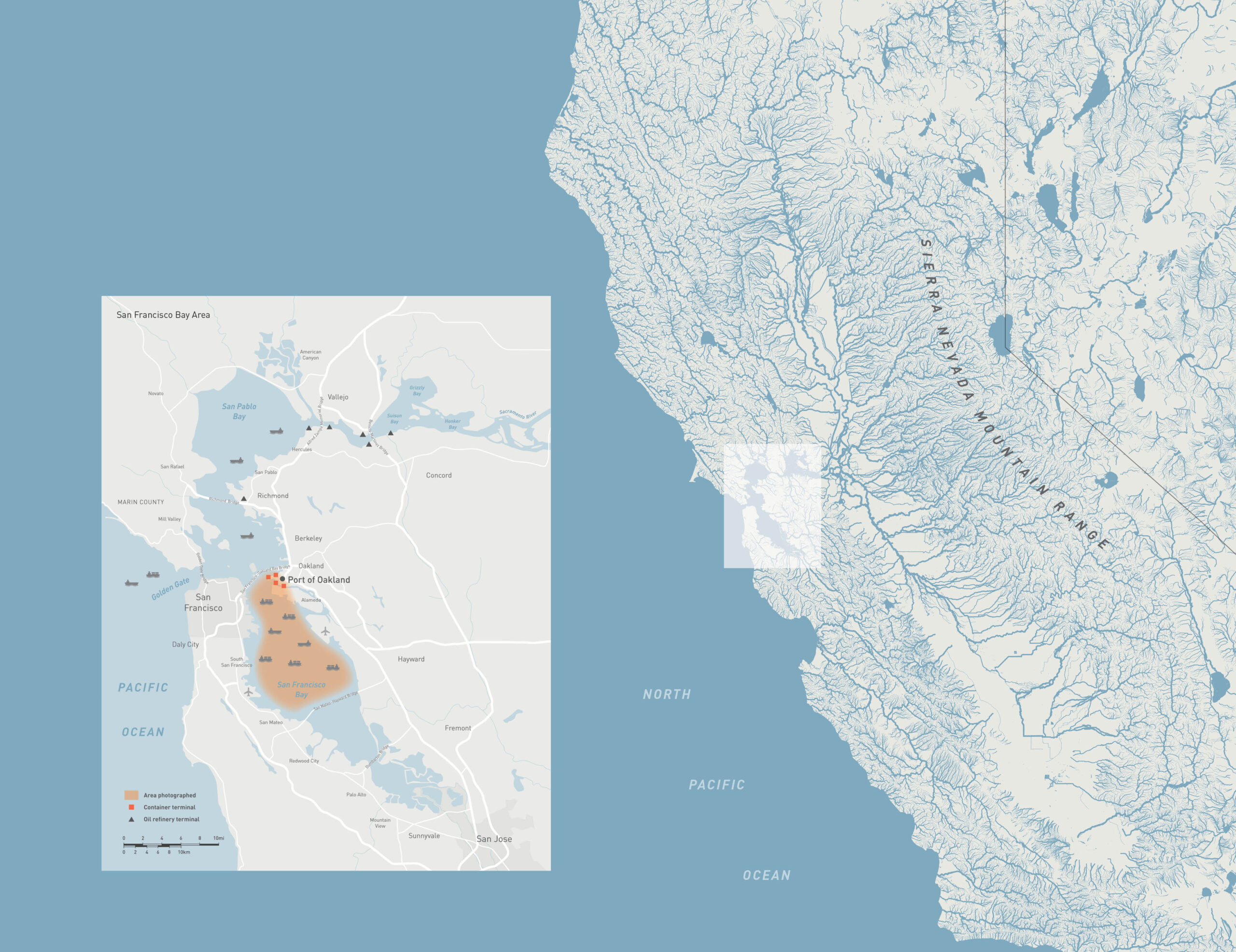

The Golden Gate is a breach in the great wall of the coast range, the one place for hundreds of miles where major waterways exit the continent and enter the Pacific Ocean. It’s a place for ships, for sea creatures, and for weather to enter. The low-lying clouds we call fog often stream through the gap in a long snaking column heading east, though other times the fog spreads more widely across land and water like a gray blanket. I say “a place” and “it,” as if it is singular, but the San Francisco Bay is many things, even by name: the Delta and Suisun Bay up where the rivers draining the Sierra Nevada meet tidal water, San Pablo Bay to the north, San Francisco Bay otherwise, with Richardson Bay tucked between Sausalito and Tiburon.

Technically, it’s not just a bay, which is merely an inlet on a body of water, but also an estuary, a liminal space where waters join, a realm between fresh water and salt water, between water following gravity downhill and tidal water undulating according to the pull of the moon. The fresh water is the result of rainfall and high-altitude snowmelt from clouds that arose over the Pacific and moved east on ocean winds, so that all these forces—the sea, the clouds, the precipitation, the snowpack and spring thaw, the bay—are one great annual pulse of water.

The bay is the terminus of this western slope’s water system and the beginning of the Pacific, which covers one-third of the globe. It mediates between the rivers and the ocean, a meeting place, a gateway. Though the term gate has been appended only to the San Francisco and Marin Headlands through which the bay meets the sea, it’s all a transition zone. US Army Lieutenant John C. Frémont gave the Golden Gate its name in 1846, as part of his campaign of American expansion, when California still nominally belonged to Mexico but was largely inhabited by the some two hundred Indigenous nations that had been here for millennia. In the Bay Area, those included the Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Pomo, Patwin, and Wappo, all of whom are still here.

To live here is to stand at the far end of what was once called Western Civilization and to know that the solid land on the other side of that largest of all wildernesses is what was once called the Far East. The Golden Gate (the subject of another Richard Misrach book) is a threshold. It is a deep gulch through which enormous quantities of water surge inward and ebb outward, by one estimate about three and a half times the volume of the Mississippi River at its mouth, on average, but sometimes twice that figure. The dangerous power of that tide is well known to those who venture into the waters.

I have spent more than half a century on the shores of San Francisco Bay, gradually learning its inexhaustible meanings and fluctuating spaces and watching the endless change of light and weather and tide, sunrises and sunsets, sunny days when the water is the color of the sky when seen from afar, even if it is green up close. On gray days, when the light breaks through but the water reflects the clouds, the bay sometimes looks like beaten silver, solid and utterly opaque. When I cross the Bay Bridge I often glance south, to where the huge cargo ships seem monumental and still, as if the arrangement were permanent, as if the vessels were knights and bishops resting on water as solid and stable as a chessboard. As if the players had left the room midgame.

These ships carry specific burdens, but they also transport the burden of the industrial age’s consumption and production and its impacts.

In another sense, the players had never been in the room but beyond it, as the multinationals that owned the ships or the products they carried, as the hands moving these pieces across the larger chessboard of the seven-tenths of the earth’s surface that is liquid, as the invisible forces behind these eminently visible large objects, as the laborers at every stage of producing and loading and transporting and unloading the goods and getting them to consumers. From the shore, the workers managing the ships are rarely seen, and nothing much discloses the content of the containers, stacked up like colossal bricks. Every once in a while a news story includes the crews and captains of vessels like these, offering brief glimpses into their lives and labor and the law of the sea and the ports.

Cargo (January 2, 2024, 7:06 a.m.)

10000.00

$10,000.00Add to cart

With the water flowing in from the heights and out through the gate, with the swelling and shrinking of the tides that mean the water’s height fluctuates dramatically twice a day, with the waves and the currents, what we call the bay is an oscillation, a nonstop process, beating like a heart and morphing like a jellyfish. A lot of its liminal edges, the former wetlands and old shoreline, have been lost to landfill, beginning with the filling in of the cove that was once downtown San Francisco’s waterline. A little monument on the pavement marks where the old shoreline was, several blocks inland from the current one, but sea level rise, driven by climate change, will take back much of what we have taken from the bay. Turning liquid into solid places began during the Gold Rush, when “water lots”—parts of the bay abutting San Francisco’s downtown—were sold off to be infilled and developed.

Huge amounts of soil and gravel from hydraulic mining (turning powerful jets of water onto the slopes of the Sierra Nevada to get at the gold) washed into the bay before the practice was banned, further diminishing its size. By one estimate, one and a half billion cubic yards of sediment were deposited thanks to this practice, along with tons of mercury, widely used in that era to refine gold, meaning that whatever profit was extracted incurred an ecological debt we are still paying. Signs around the bay in English, Spanish, Tagalog, and Chinese have long cautioned anglers about mercury poisoning if they eat their catch, but miners from the nineteenth century are still poisoning children born in the twenty-first. The same could be said of the fossil fuels moved in such alarming abundance in and out of the Bay, to and from the refineries in Richmond and the Carquinez Straits: the profit will burn up as fast as the gasoline, but the consequences will be with us for millennia.

Richard Misrach, Cargo (January 17, 2022, 5:33 p.m.)

In the postwar era, many plans were made to fill in more or most of the bay, with the logic that liquid spaces are useless and should be turned into solid land for development. Sylvia McLaughlin, a wealthy Berkeley resident, helped found Save the Bay in 1961 to push back at these land grabs, and part of the East Bay shoreline that was preserved now bears her name. In her oral history, she remembers seeing dump trucks going down to the shore to deposit their loads. She remembers the stench of raw sewage, the shoreline heaped with discarded junk. The bay was imagined then as a sewer to dump things into, as a void to be filled. That it was an ecosystem, a beautiful and valuable part of nature, at the heart of all this human development was largely ignored in that era. Now it is seen more clearly as a wilderness as well as an industrialized space and is more widely protected. Along some stretches wetland restoration has taken place. But the ships still come.

There are so many kinds of invisibility here. The opacity of the water in all but the shallowest, calmest stretches means the vast underwater world is easy to ignore, though seaweed and shellfish are visible at low tide and dead creatures wash ashore along with debris. After storms, twigs, branches, and sometimes trees ride the waters. After a major storm, soil washes into the creeks, rivers, and bay itself, forming a tongue of brown water that extends far beyond the Golden Gate. The bay is treacherous in many ways—much of it is too shallow for large vessels, obstacles stud it, the force of tides and storms can be colossal. Pilot boats and tug boats are required to guide oceangoing vessels into the bay. Among the other things underwater around the mouth of the Golden Gate are shipwrecks from the days before GPS, radar, and other navigational technology. The foghorns are relics of that era, when sound served ships whose crew could no longer see any distance.

Wildlife still abounds: fish—sometimes in astonishing if fading abundance as herring runs and salmon migrations—seals and sea lions, crustaceans and shellfish, shorebirds and seabirds. But even the whales that occasionally swim under the Golden Gate Bridge are dwarfed by the ships. The ships are troublesome reminders of industrial civilization at its most aggressive, behemoths that cross the Pacific to feed American appetites for fuel and manufactured goods. The goods are now mostly unloaded in the Port of Oakland. The oil tankers go to the Port of Richmond, where oil from California, Alaska, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and Ecuador is piped to the Chevron Richmond Refinery and other fossil fuel companies in the vicinity. Half of the oil extracted from the Amazon goes to California, where it is turned into jet fuel, diesel for delivery vehicles, and gasoline. The ghosts of the rainforest are part of what haunts the Bay.

The ships are protagonists in the drama of the changing climate, though that too is among the things that can be understood but not seen directly. Four tenths of the global shipping industry’s activity is moving fossil fuel around, because the stuff is so unevenly distributed across the earth and the appetite for it so voracious. When we transition away from fossil fuel, the comparatively even distribution of sun and wind across the globe means that much of this traffic will become obsolete. In that context, you can look at these ships as a threat and trouble as part of their cargo. And you can see sunlight as another protagonist visible in all these pictures, see wind discernable in the rough surface of the waters.

Time itself is invisible when it operates on scales longer than our attention spans, when we fall prey to thinking that what looks stable on the scale of a day or a decade is stable, when we fail to gather the sources that let us know that stability is just a snapshot decontextualizing instability. Understanding this place requires an imagination that reaches beyond the visible to scales of time and space the eyes cannot take in but the imagination can. A photograph is a moment, a fraction of a second to a few seconds, of time; but the Bay in its current size and shape is also a finite era in time that is coming to an end. This knowledge is cargo we all carry.

All photographs © Richard Misrach

This essay originally appeared in Richard Misrach: Cargo (Aperture, 2025).