Photobooks

Roï Saade Is Building a New Photobook World

The designer and roving archivist creates networks for artists and photobook publishers across the Middle East and North Africa.

In 2022, the Lebanese-born photographer and designer Roï Saade founded Bound Narratives, a roving archive, workshop, and exhibition program conceived to promote photobooks by Middle Eastern and North African artists. Packing his library into several suitcases, Saade has brought Bound Narratives to Beirut, Florence, Montreal, and Sarajevo, and plans to soon take it to Tunis and Egypt. Here, he discusses the struggle against Eurocentric publishing norms, his process-driven approach, and how photobooks can redraw lines of belonging.

Dalia Al-Dujaili: Tell me about your journey into bookmaking, curation, and design.

Roï Saade: After a few years in the corporate world, I felt the need to get out of it and work toward something more creatively fulfilling. While studying graphic design at USEK University, in Lebanon, I had taken some photography courses. I found that photography was a means to access communities that I don’t belong to, to break these religious and social barriers and just explore Beirut.

And photobooks allowed me to work at the intersection of design and photography. As an editor, I want to recognize work that is not being acknowledged by the industry’s gatekeepers, and to counter stereotypical depictions of West Asia and the Arab world. My practice is very research-driven and relies on close collaboration with other artists. I’m attracted to the process rather than the end result.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Al-Dujaili: Can you tell me about the motivations behind Bound Narratives?

Saade: Bound Narratives is a growing archive of photobooks from and about the MENA [Middle East and North Africa] region. It strives to build a broad and open repository of visual materials to stimulate education and critical discourse through photography and digital narrative. In doing so, the archive seeks to remedy an imbalance of cultural knowledge between the Global South and North. The MENA region is very familiar with the American and Eurocentric canon of photography. Our bookstores, libraries, and homes are filled with Western photobooks. Yet it’s rare to find photobooks from the region itself in these collections. It was first an internal critique.

We have no shortage of artists or storytellers. In fact, it’s the opposite. We have an overwhelming amount. It is the economic and political realities—and the lack of resources and publishers—that disconnect us from each other and from the world. We depend heavily on the West to acknowledge us first and publish our work. And that’s why my initiative is to try to create exposure, however minimal it is. Whatever the problems are, try to solve some of them yourself. So, I started a public inventory and started asking my network of artists to share photobooks by artists in the region.

Al-Dujaili: I’m wondering what the challenges are. I know you live and work in Canada, but you also do work in Lebanon and in the region as well.

Saade: Yeah, I work and live between Lebanon and Canada. The challenges are economic, no doubt. We can’t underestimate how the lack of resources and money control what is being seen and how it’s being seen. Most of the artists I collaborated with are self-published. Everyone is struggling, fighting for crumbs from Western institutions. And so, you have to try to be creative. You’re very limited, and in these limitations, you have to dance and find ways. By contrast, when foreigners parachute to our region to work, they get easily published by someone in the West. It’s very interesting to see that struggle for locals to amplify their voices while foreigners are easily published. At the same time, you can also see a pattern where most of the published artists from the region get to be published in the West by either immigrating, or by living for a period of time or creating these networks in, let’s say, France or New York. When it’s not foreigners, it’s mostly diasporic artists who get wider visibility.

I’m interested in showing these books to local Middle Eastern and North African communities—for them to see what has been produced and what are these cultures around them that are so disconnected and so disrupted by regional politics. I also want to share them with the Global North to say: These narratives exist. There’s more than one modernity and contemporary. There are so many worlds in one world, and they can all fit together.

I see this project as helping to mitigate the construction of otherness.

Al-Dujaili: I love that, many worlds in one world.

Saade: With Bound Narratives, I focus on the book’s journey after its production. It’s a correspondence of the past and the present. It’s an exchange between the artist and the viewer. People sit on the carpets and focus on the book and consume it as a ritual. At Bound Narratives, you don’t have to buy a book. You can come to this gathering and look at the books and experience these books without the need of a financial transaction. What’s important is people being together, studying, playing together.

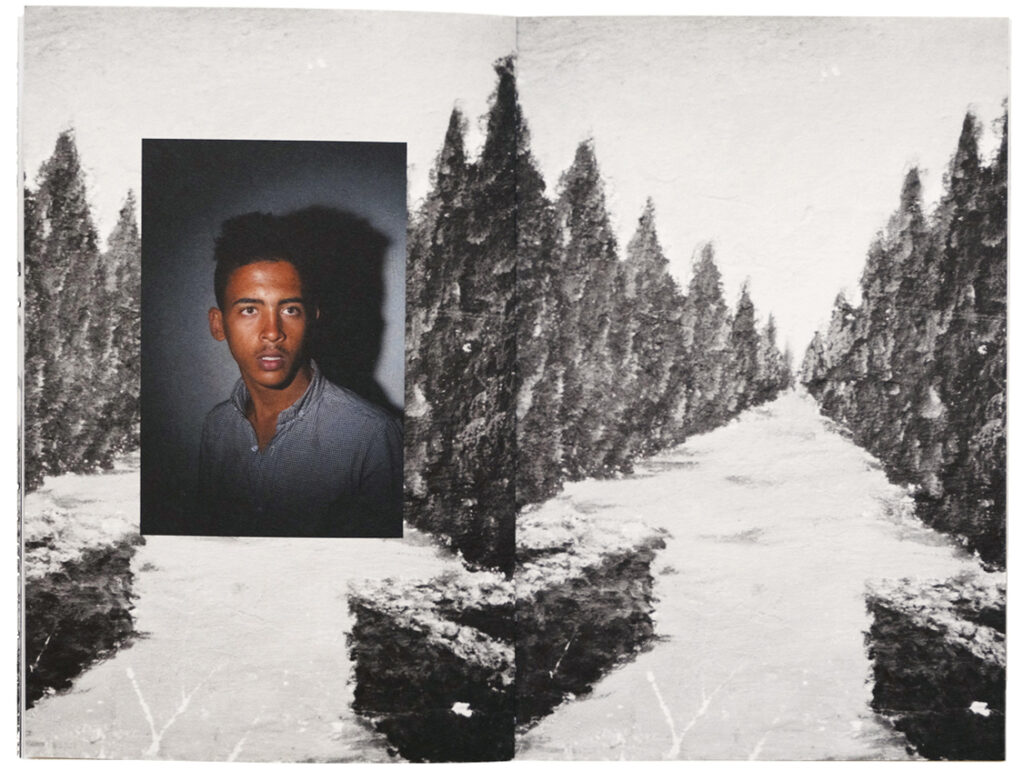

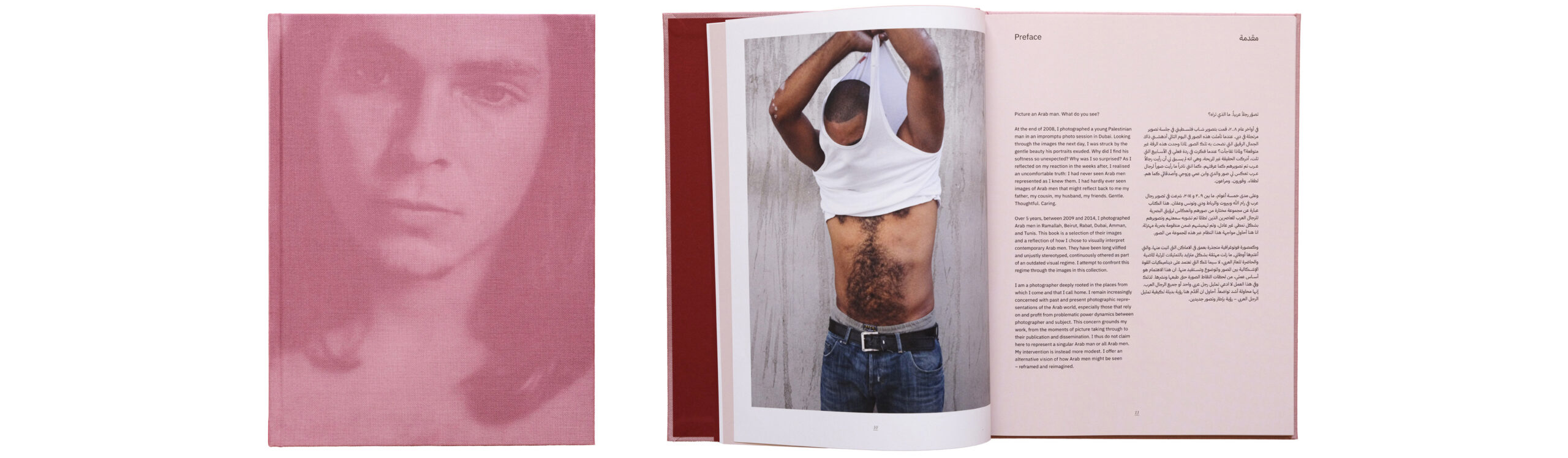

Cover and interior spread of Tamara Abdul Hadi’s Picture an Arab Man (We Are the Medium, 2022)

Al-Dujaili: In 2022, you designed Tamara Abdul Hadi’s Picture an Arab Man.

Saade: Tamara’s book is an attempt to reframe the visual representation of contemporary Arab men. The design choices were informed by how she sees her father, how she sees her cousin, her nephew. So much of the effort was put into small, subtle details—the texture of the cover, the weight of the paper, the bouncing of reflective colors, the empty pages, the repetition of cropped images. I love this cover and the burgundy color of its endpaper. Her father is included. He was an amateur photographer, and she’s very inspired by him. The linen texture—how the image almost fades inside it—contributes to an ambiguity we were trying to communicate, as well as the softness and beauty that is very absent in mass-media representations of Arab men.

Al-Dujaili: That year, you also designed Dry, the second photobook by the Algerian photographer Abdo Shanan.

Saade: Abdo was very generous and trusting from the start, which is key to any collaboration. He gave me full access not only to his body of work but to his ideas, to his history. It’s about struggling to belong to a place that you feel doesn’t want you. I can relate to that in a way, given Algeria and Lebanon’s history of colonization. During the making of the book, I looked at the history behind these uprooted feelings to better understand the experience of postcolonial struggle. I read Frantz Fanon for the first time. I read The Wretched of the Earth (1961) and Black Skin, White Masks (1952), which informed my editorial and design decisions. Later, I read Colonial Trauma (2021) by Karima Lazali, which ended up being part of the book.

Al-Dujaili: That’s an insert in the book?

Saade: Yes. It’s a beautifully written insight into the psychopolitical effects of colonialism in Algeria. It fits very well in Dry because there are the personal stories and the collective reckoning with inherited trauma. Both Shanan, who is Algerian Black with mixed ethnic parentage, and the people he photographed are confronting their conflict with belonging. The book opens with a kind of descent. We see his window. Then, we go downstairs into a cemetery, and it’s silver ink on black paper. Then, his hand and his imaginative world. And then you start the book.

Al-Dujaili: You’ve named Samer Mohdad, the Lebanese Belgian photojournalist, visual artist, and writer, as an important influence.

Saade: Mohdad’s Mes Arabies was essential to my beginnings. It was a revelation seeing Arabs portrayed outside of an anthropological and orientalist framework. When I saw the work, I was just beginning photography. It was published in 1999. It’s one of the oldest books in my collection, actually. It’s a very ambitious, rare document of a specific time in the Arab world. He journeyed around twelve countries and documented humble people he met along the way. I find that everyone in his book has pride and respect. He doesn’t fetishize or glorify his subjects.

Al-Dujaili: I’m curious about other books that have inspired you.

Saade: I love Nadhim Ramzi’s Iraq: The Land and the People (1977). I relate to him a lot because he was a graphic designer and photographer, like me. He’s one of the rare photographers we know about from the older generation, other than Latif Al Ani from Iraq. Many photographers existed and still exist, a huge variety, but it can be a challenge to find and access their work.

And there’s Maen Hammad’s book Landing, which layers journal entries, poetry, and images to talk about Palestinian resistance through the eyes of young skateboarders, framing the act of skating as a purposeful escape. Landing is one of the projects that continued to evolve way after I began working on it. Maen came to me with a group of images to create a standard photobook, but after I read some of his very eloquent writing, I suggested he write more. A month or two later, he came back to me with so many insights about Palestine. He shared facts; he shared stories, including his personal stories; he shared poems he wrote.

When you’re dealing with a subject such as Palestine, you want to inform people about the geopolitical context of the place and not just rely on their interpretation of things. When I exhibited this work in Italy, I emphasized to Maen that some images need captions. For example, a refugee camp that is the most tear-gassed place in the world. The museum fought to remove these captions. They wanted to remove information about who inflicted this pain—the Israel Defense Forces—but they had no problem with presenting the Palestinians as victims.

Al-Dujaili: What’s next for Bound Narratives?

Saade: Bound Narratives is expanding. This includes digitization, exhibitions of photobooks and images in galleries and pop-up spaces—like Takeover, in Beirut—along with talks and workshops around the book form. I’m hoping to find funds to create an online repository and commission artists, writers, and academics to engage with the library. I prefer this localization of situated knowledge. I think universalism, more often than evoking all of us, imposes one narrative and determines its value. I see this project as helping to mitigate the construction of otherness—how we’re always creating barriers and categorizing others.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture no. 256, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” in The PhotoBook Review.