Essays

Seydou Keïta’s Revelatory Portraits of Malian Life

In midcentury Bamako, sitting for a portrait in Keïta’s studio was a defining assertion of identity.

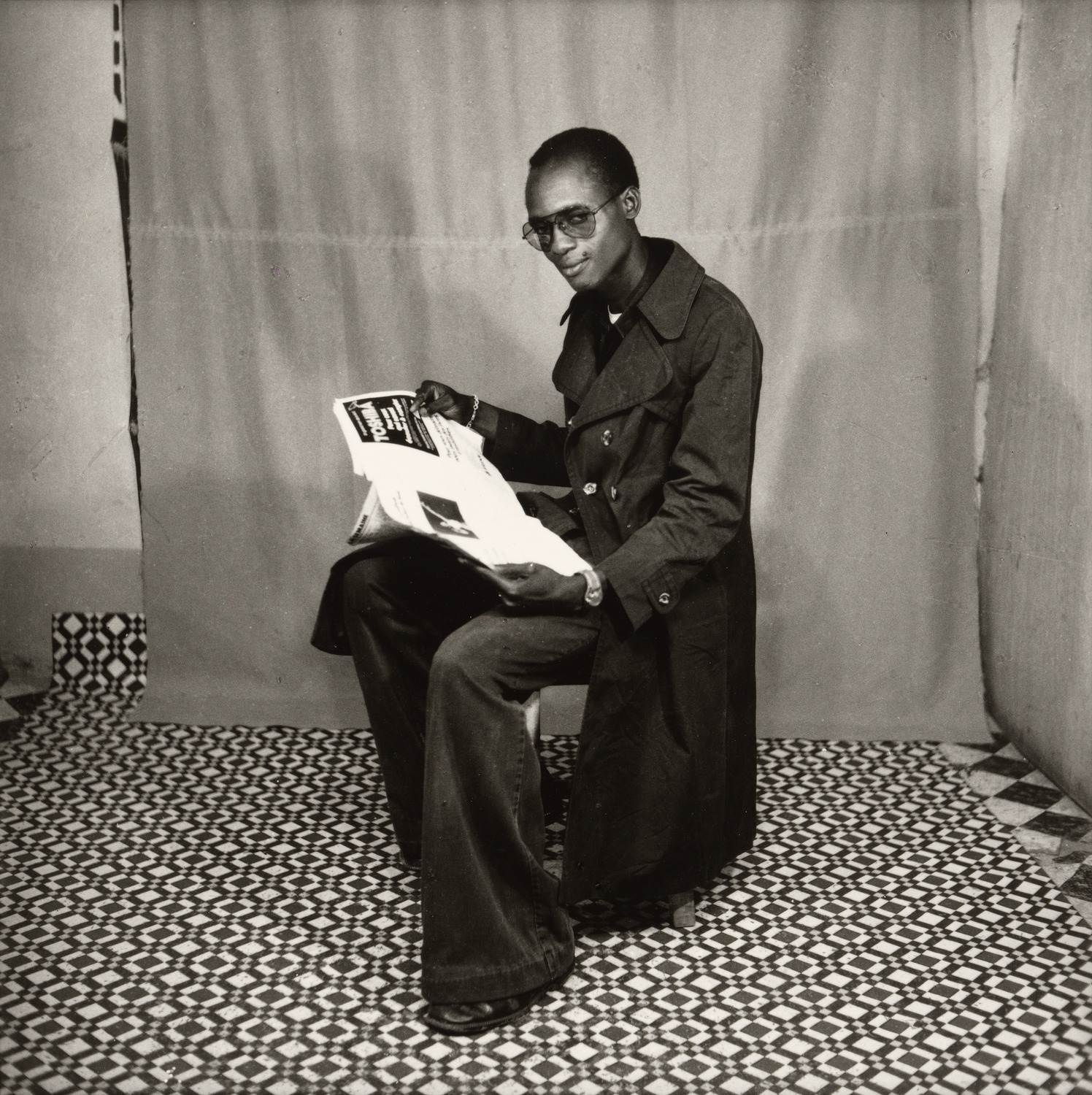

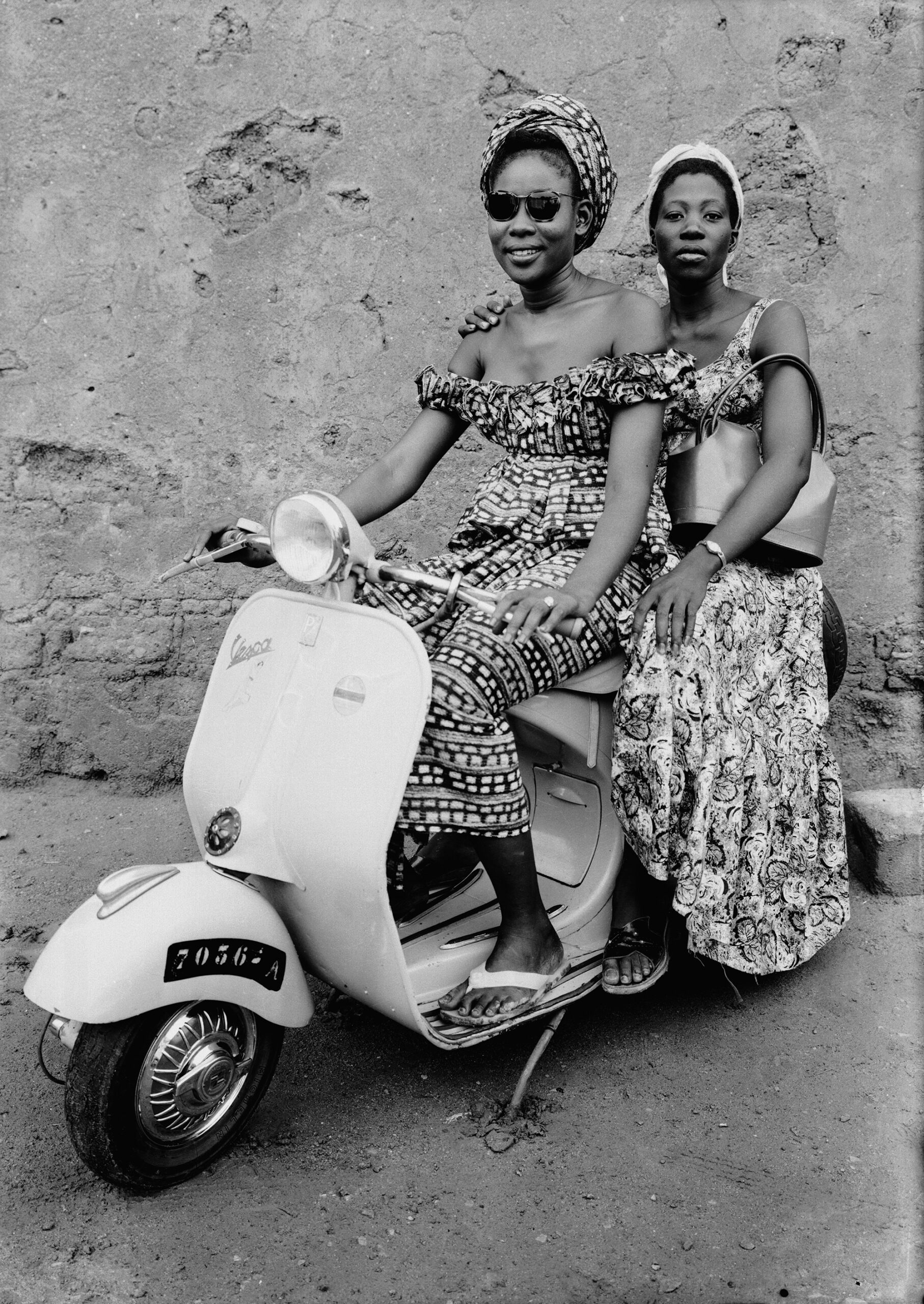

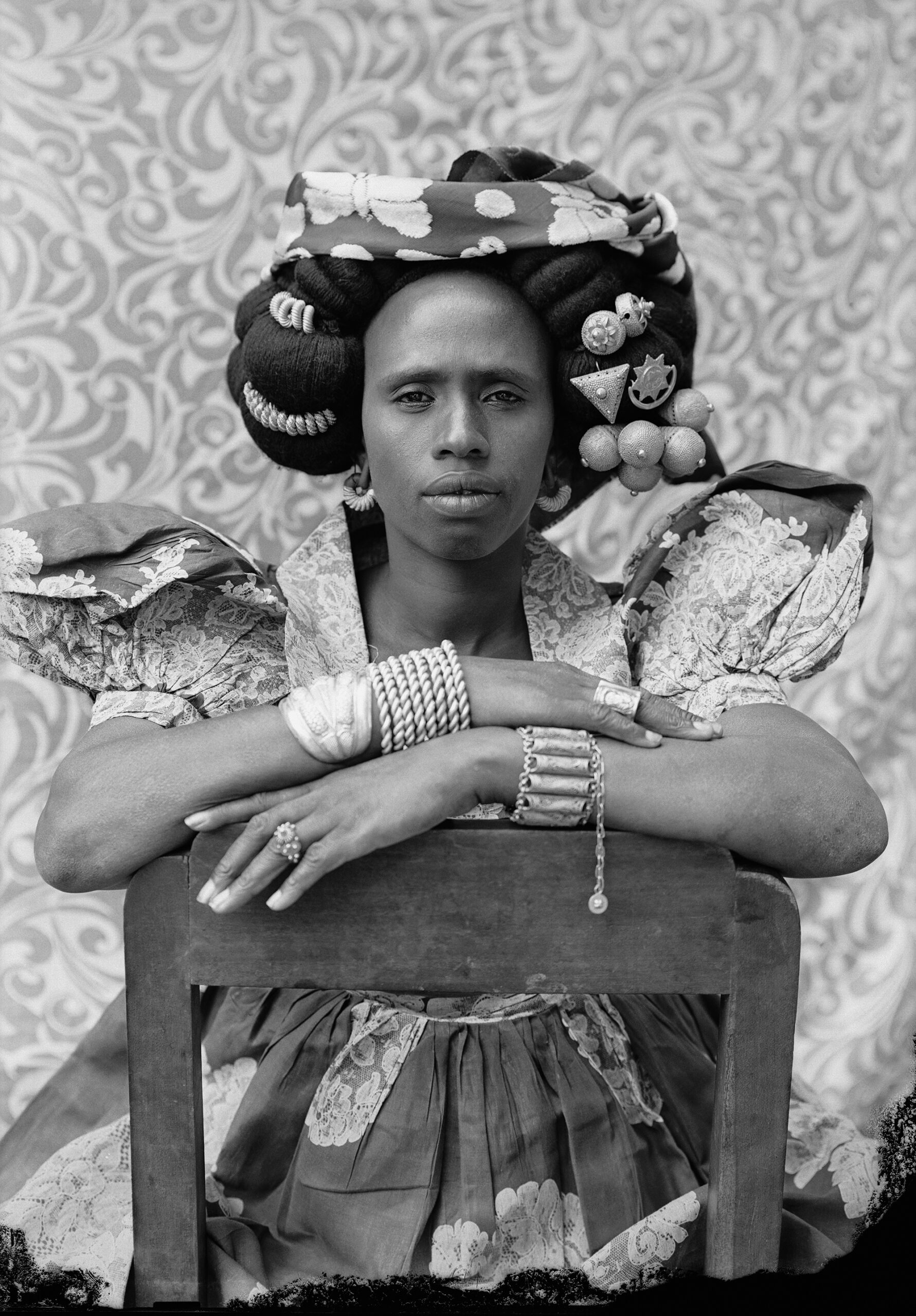

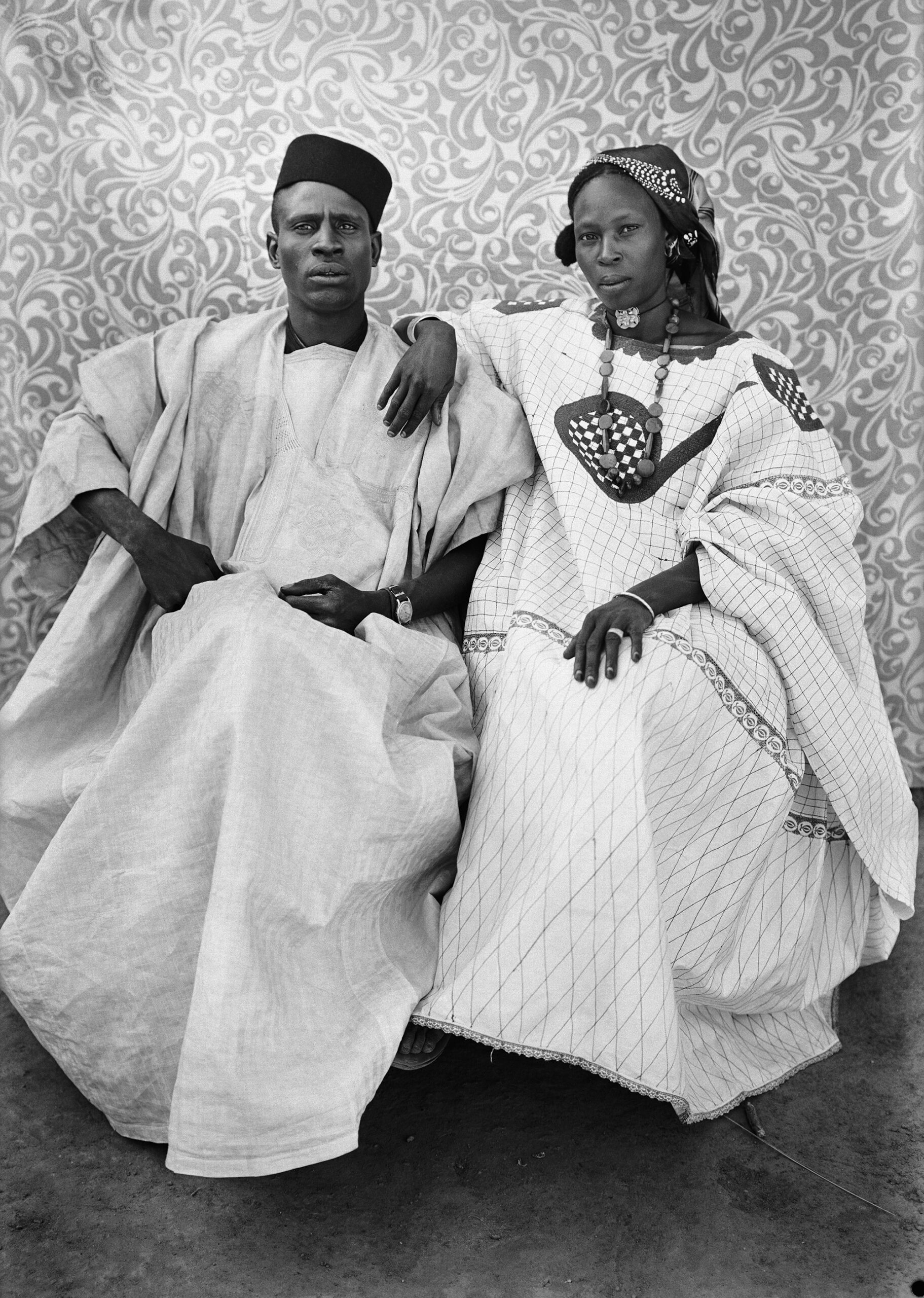

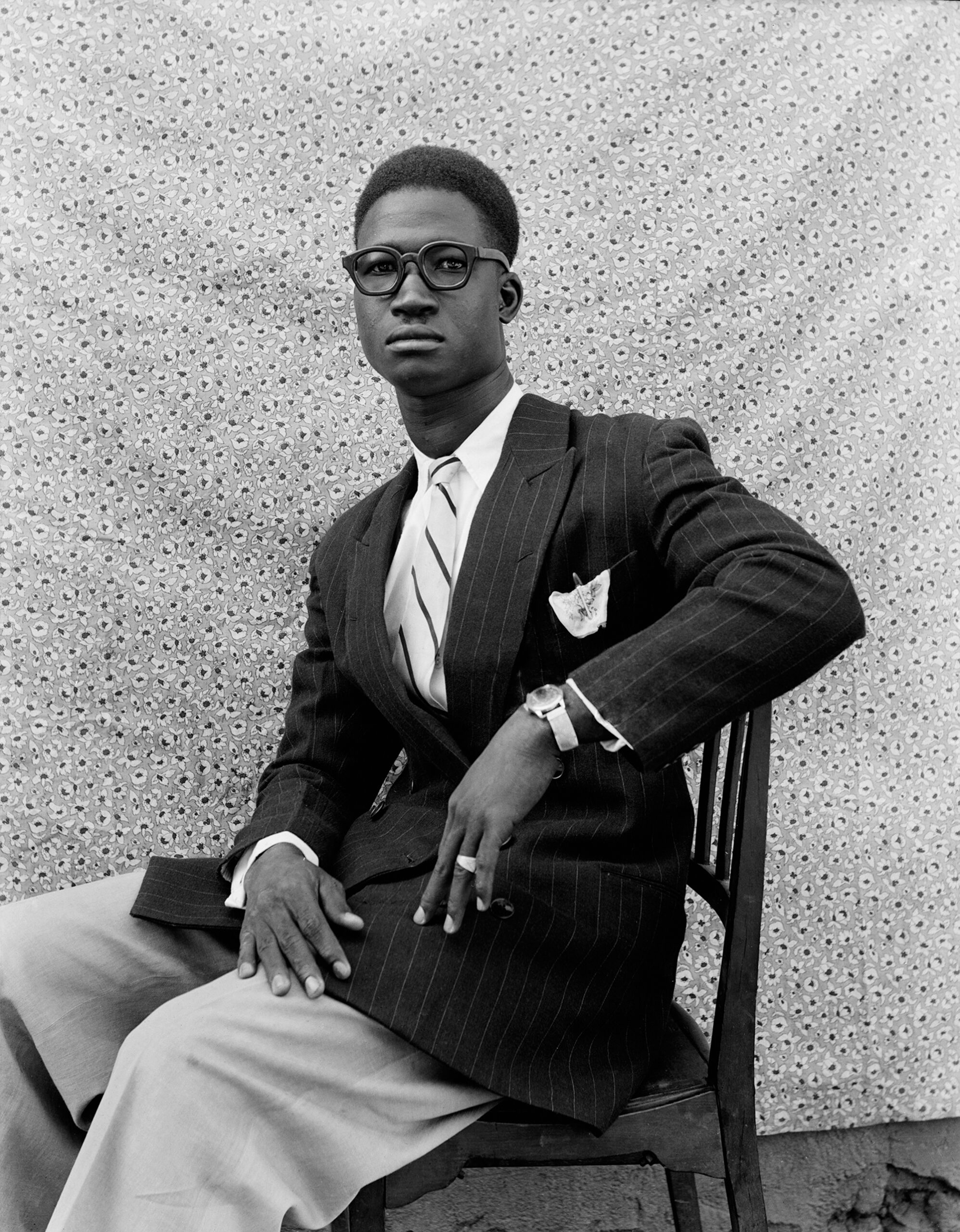

A young woman gazes confidently at the camera, her black hair adorned with white cowrie shells; a man poses in a sharply tailored suit and glasses, embodying an elegance that is at once African and European. The act of sitting for a portrait in Seydou Keïta’s studio was a quiet but deliberate assertion of identity in a heady age of self-determination.

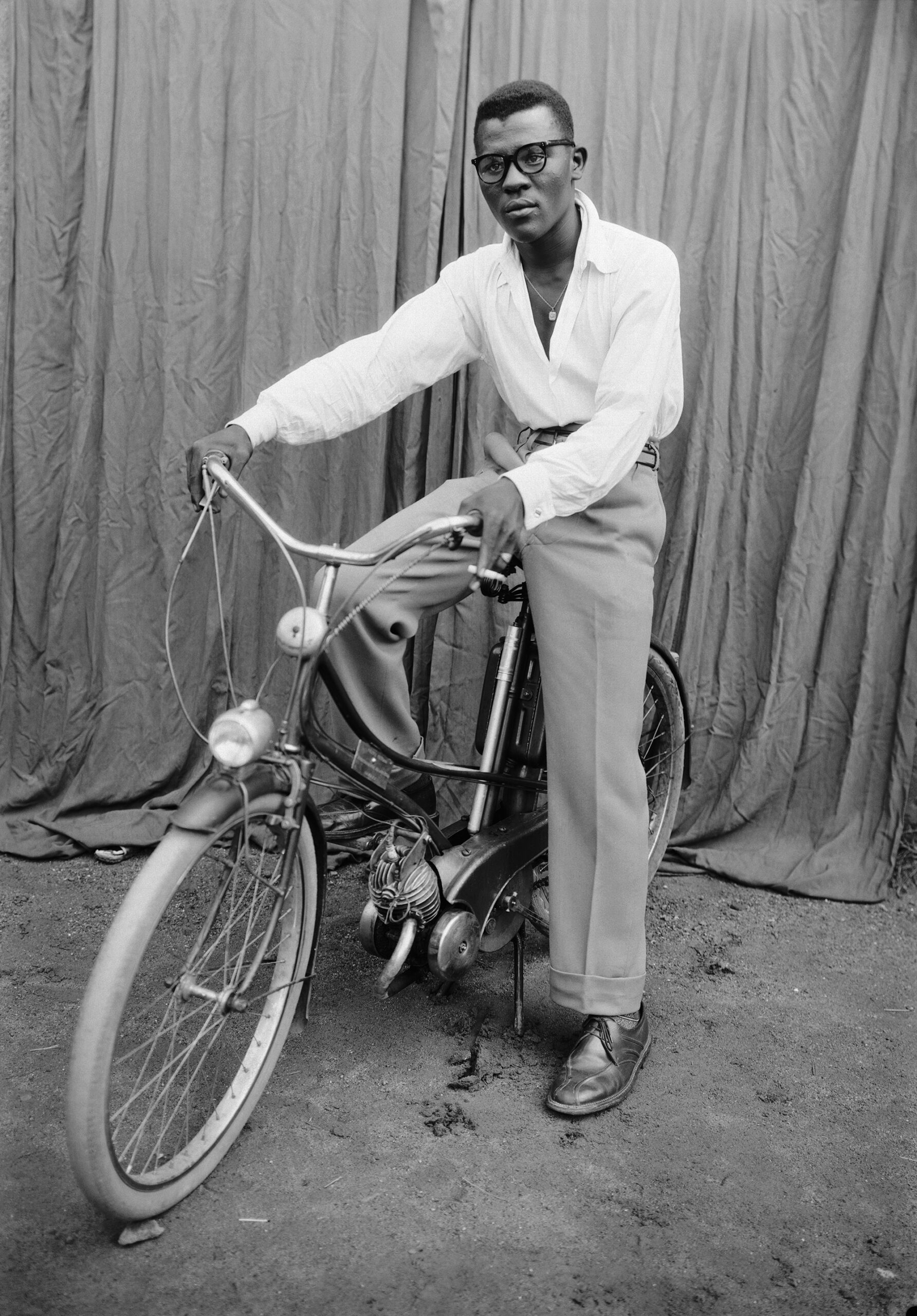

Taken mostly between the late 1940s and 1960s, Keïta’s portraits are master classes in texture and composition. His studio—located on land his father gave him behind a prison in the Malian capital city of Bamako—welcomed a diverse range of visitors after its 1948 opening, from government officials, traders, and intellectuals to artists and everyday members of Mali’s rising middle class. Some went to the studio for professional pictures; others went to record their growing status and personal achievements in ways that could be hung on the walls of their homes, stored in family albums, or given away as gifts. Much like the highlife music that would soon become the rage across West Africa—a genre blending traditional African elements with Western influences, creating the aspirational soundtrack to African independence—Keïta captured not just the aesthetics of an era but the ambitions of a people. His process was meticulous. Known for his patient, precise use of a large-format camera, he favored natural over artificial light. His signature use of shallow depth of field ensured that attention remained on his subjects and their attire, creating an intimacy that distinguished his work from more conventional studio photography of the time.

Moreover, as the late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor—one of Keïta’s foremost champions and exegetes—has noted, the photographer conceived of his studio as a porous site, forgoing the late-Victorian device of painted, idealized backdrops for quotidian, ever-changing textiles that allowed him the flexibility to make work in various settings. “Any space could become a studio for Keïta,” Enwezor wrote in 2010.

Born in Bamako in 1921, Keïta began his journey with photography in 1935 at the age of fourteen when his uncle gave him a Kodak camera. He would eventually work with Mountaga Dembélé, a former schoolteacher who shifted careers to become one of Mali’s first professional photographers. At one point, Dembélé entrusted all his photographs to Keïta, prompting some scholars to question the distinction between their images, though others contend that the difference is immediately evident to anyone who looks closely: Keïta’s portraits employ a more deliberate construction, whereas Dembélé’s feel spontaneous and raw. In any case, both men are rightly venerated in Mali—and beyond—as the country’s photographic pioneers.

Today, Bamako’s long roads weave between colonial-era buildings and new developments. The city is situated along the banks of the Niger River, where its pirogue boats, carved from single tree trunks, drift past colorful markets, echoing its past as a vital crossroads along ancient trade routes linking West Africa to North Africa and farther regions. Bamako was once a key city in the ancient Mali Empire, which flourished across West Africa from the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, its heart being the legendary Timbuktu. Posterity remembers the empire’s ruler Mansa Musa I as arguably the richest person in history (with a net worth of around $400 billion when adjusted for inflation), thanks to Mali’s vast gold and salt reserves, and for his legendary pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, during which his lavish distribution of gold caused inflation in Egypt.

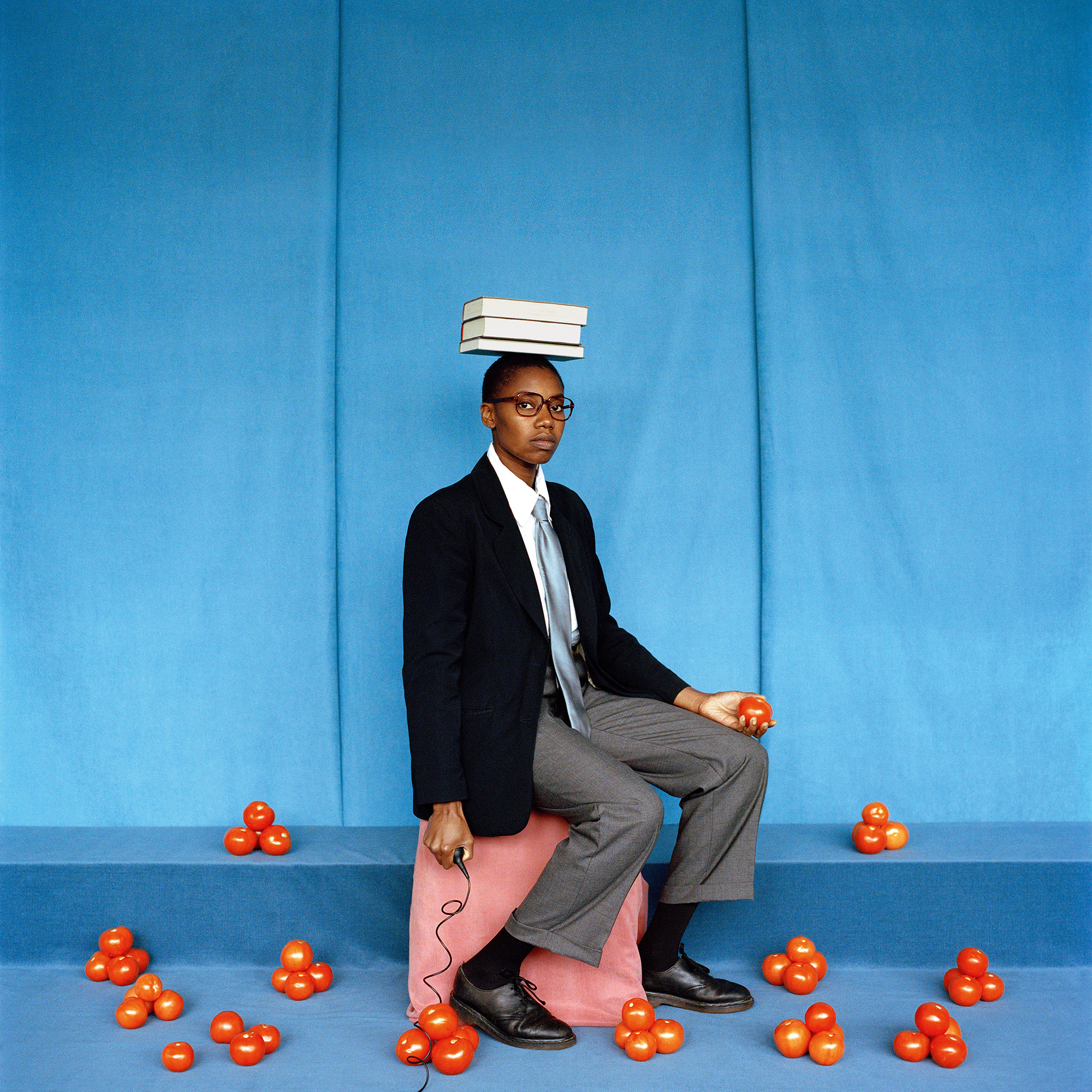

Now a nation, Mali remains a creative hub where tradition merges with contemporary global influences. Its musicians are internationally renowned, ranging from the soulful sounds of icons such as Salif Keita and Oumou Sangaré, to the African blues of Ali Farka Touré and Tinariwen, to the Afropop fusion of the likes of Fatoumata Diawara. Bamako is Mali’s capital and one of Africa’s largest, most populous cities. Since 1994, thousands of photographers, filmmakers, and art enthusiasts have gathered there for Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie, widely known as the Bamako Biennale, Africa’s first and largest photography event, consisting of a large program of exhibitions, talks, and meetings.

In the middle of the twentieth century, however, Bamako was in a state of acute sociopolitical upheaval, its people watching while the might of France fell at their feet. The city bore the weight of colonial exploitation from the late nineteenth century until Mali wrested freedom back in 1960. Even as France urged its colonial subjects to prioritize European fashion over their own, the people of Mali simply integrated it into their existing styles. While European fabrics, including damask and wax prints, now synonymous with African fashion, became symbols of cosmopolitanism, traditional mud cloth (bògòlanfini), indigo dyeing, and intricate embroidery remained embedded in the social and spiritual fabric of the region, forming the foundation of its material culture. Such textiles appear throughout Keïta’s photographs, connecting his sitters to both tradition and global influences. Retaining a connection to the former was an important act as the colonial project attempted to supress everything culturally African that it could not extract and plunder.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Although he is now celebrated as one of the most accomplished photographers of the twentieth century, Keïta remained largely unknown in the West until the early 1990s, when some of his photographs (uncredited at the time) that were shown at an exhibition in New York came to the attention of the French curator André Magnin. This set in motion a mission to Mali to find Keïta and introduce his extraordinary portraiture—consisting of thousands of images—to a global audience. Others, including the photographers Bernard Descamps and Françoise Huguier, who presented his work at Les Rencontres d’Arles and at the Bamako Biennale, would also help introduce the work to new audiences.

This success has not, however, come without controversy. Some have questioned the commercialization of Keïta’s portraits, and the way their deep cultural ties to Mali are often diminished when framed for the Western art market, a debate that, in turn, connects to broader issues of appropriation and exploitation of African art within global networks. In Keïta’s case, his prints were upsized, from their original, modest dimensions of 5-by-7 inches, for the contemporary market and an imagined clientele purchasing art at blue-chip galleries like Gagosian and Sean Kelly. An illuminating 2006 article in the New York Times by Michael Rips outlined the multipronged, dramatic saga and litigious debates around the authenticity of some editions produced after Keïta’s death.

This fall, the Brooklyn Museum, in New York, will hold an exhibition that represents an opportunity to once again assess Keïta’s contributions. The show aims to situate Keïta’s genius within its cultural and historical context, and to highlight his family’s role in preserving his legacy. Catherine McKinley, author of The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women (2021), is curating the exhibition. When I spoke with her last winter, she explained that it will allow visitors to immerse themselves in Keïta’s world. His photographs will be displayed alongside textiles and ephemera loaned from the archives of numerous contemporary Malian and Senegalese scholars, collectors, and designers. Highlights include an intricately hand-stitched indigo camisole from 1902 and a women’s pagne (wrapper) from the Musée de la Femme Henriette-Bathily in Dakar that almost perfectly replicates one seen in his pictures.

Unsurprisingly, his work, with its precision and exquisite clarity, has drawn comparisons to August Sander’s portraits made in Germany in the early twentieth century. Keïta’s photography is likewise rooted in the culture and currents of its time. “Keïta crafted a distinctive modernist photographic language anchored in the Malian arts of textile,” Giulia Paoletti, associate professor of African art at the University of Virginia, told me. The cultural and economic forces shaping Keïta’s work were deeply diverse and intertwined. Jennifer Bajorek, an associate professor specializing in literature, art, and visual studies in contemporary Africa at Hampshire College, added that “his photographs bear witness to longstanding histories of trade, trade routes, and zones of cultural and economic exchange. They reveal and carry counter-colonial geographies. This is part of their extraordinary legacy.”

Keïta’s images offer windows into a world where individuals claim space within a rapidly shifting society.

Bajorek is critical of earlier scholars’ preoccupation with whether the textiles in Keïta’s photographs were African or European, given the many cultural currents these objects embody. By way of example, she points to the sanu koloni gold choker worn by many women who went to Keïta’s studio. Its name—meaning “colony gold” in Bambara, a language spoken across Mali—acknowledges its colonial ties. Yet its cruciform shape and five raised points reflect Maure and Amazigh designs, with jewelry historians tracing its craftsmanship and aesthetics to Jewish goldsmiths from the Maghreb, whose techniques and motifs influenced adornment traditions across the region. Bajorek noted that items such as sanu koloni and koso walan—a dark-blue-and-white checkered strip-woven blanket often seen as a backdrop or mat in Keïta’s pictures—possess both colonial history and cross-cultural influences. “A community’s relationships to indigo and indigo-dyed textiles, the protective properties of the number five, the influence of Islam, ideas of Blackness associated with gold, the spiritual as well as material legacies of a millennium of Saharan crossings—all of this is there and, in its way, visible or traced in the photographs made by Keïta in his Bamako studio,” Bajorek said.

More recent history and events have hampered ongoing studies and engagement with Keïta’s pictures and legacy. In the spring of 2024, McKinley traveled to Mali to meet with the Keïta family as part of her research. But with the ongoing conflict in Mali—which began in 2012, when northern insurgents sought independence—she extended her search beyond the country’s borders, delving into archives and collections within the large Malian communities of Dakar and Saint-Louis in neighboring Senegal to gather the pieces that will help bring Keïta’s work to life in the upcoming exhibition.

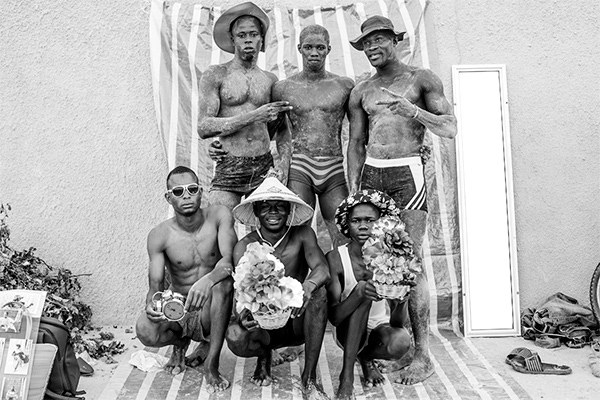

With its stronger colonial ties and more urbanized infrastructure, Senegal’s long tradition of studio photography dates as far back as 1859. In contrast, Mali’s first studio was established by the Frenchman Pierre Garnier in 1935. Garnier trained several of Mali’s earliest photographers, including Dembélé, but it would take another decade before they would start producing their own studio photographs, opening the door for others, such as the legendary Malick Sidibé, who looked up to Keïta and called him “the Elder.” Keïta’s formal studio portraits not only capture the elegance and aspirations of post-colonial Mali, but also reflect the growing desire for independence, eventually achieved in 1960. In contrast, Sidibé’s candid nightlife photography, which flourished in the 1960s and 1970s, conveys the energy and popular culture of a nation embracing its newfound freedom. Together, they paint a dynamic portrait of a country in flux.

Mali’s relatively late start in photography turned out to be a blessing, allowing its photographic culture to develop with greater freedom from the colonial conventions that defined Senegal’s numerous, more formal studios. Keïta was arguably the first Malian photographer to fully embrace this freedom. So formidable was his craft and reputation that in 1962 he was appointed Mali’s official state photographer. The arc of his career was punctuated by the progression of Mali’s history, all the way from how his portraiture mirrored the high cosmopolitan hopes that followed the country’s independence, to the military junta that pushed him into retirement in 1977 at the age of fifty-six. At this point, Keïta started pursuing his second passion: auto mechanics. Moving from photography to working on cars may sound like quite a switch, but it had been a passion of Keïta’s before his uncle put the Kodak in his teenage hands. It afforded him a more sedate life, away from the politics of the time. Having been originally trained in the family business of carpentry and furniture making, Keïta had always been a man of his hands. McKinley sees a kind of consistency here: “He was a real technical guy. He liked to tinker and learn and take things apart completely and reconstruct them. That was kind of his nature. He did it with cars, he did it with cameras and everything.”

Keïta died in Paris (where he had traveled for medical attention) in 2001 at the age of eighty. Today, the Bamako property his father gave him can still be found with his family’s name hanging from its tall wrought-iron gate. His legacy within Mali remains strong, with his prints found in places such as the Musée National du Mali, which showcases the country’s cultural heritage and history through an exceptional collection of traditional and contemporary art, including sculptures, textiles, historical artifacts, and photography by the likes of Keïta, Sidibé, and others. “Keïta is widely revered in Mali today,” said Antawan I. Byrd, a photography curator at the Art Institute of Chicago who has worked in Mali. “And his legacy is affirmed through symbolic gestures such as the Grand Prix Seydou Keïta Award, the top prize given at the Bamako Encounters Biennial of African Photography. Yet, despite the international visibility and acclaim his photography has rightfully achieved, Keïta remains, in many ways, a mythologized figure. There is still much to explore and critically examine about his practice.”

All photographs © SKPEAC/the estate of Seydou Keïta and courtesy The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

This mythologization stems in part from how Keïta’s work has been understood within global art circles as a singular, almost omniscient eye of post-colonial Mali, widely celebrated yet often removed from the complexities of his working conditions, the commercial nature of his practice, and the broader photographic landscape of Bamako at the time. As a studio photographer, Keïta primarily responded to the needs of his clients, creating portraits that reflected their aspirations in a season of change. Unlike many modernist photographers in the West, he did not fetishize authorial control, and likely considered himself both a craftsman and an artist. While shaping images to meet demand, he was acutely aware of the times in which he lived but may not have consciously curated the legacy he has left behind. Over time, Keïta’s work has been imbued with layers of meaning—revered as both documentary and art—even while it is sometimes unmoored from its original context, a recurring problem in the circulation of African photographic archives.

Keïta’s images offer windows into a world where individuals claim space within a rapidly shifting society. They are living archives, constantly being reinterpreted through contemporary perspectives. They show the enduring power of photography to capture more than mere aesthetic. In contrast to the colonial photography that came before Keïta, which presented the African as mere object, his subjects gaze directly into the camera and claim their place in history on their own terms. Yet his work endures as not only a quiet defiance of colonial narratives but a testament to his mastery. His images do more than resist; they honor, elevating each subject with a care so profound that their presence, etched by Keïta into history using shadow and light, feels both intimate and monumental.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”