Portfolios

Silvia Rosi Reimagines the Family Album

In her performative self-portraits, Rosi speaks to experiences of the African diaspora across Europe.

Silvia Rosi picked up photography in her teenage years, documenting friends and family in the northern Italian region of Reggio Emilia, to which her parents had immigrated from Togo in the late 1980s. Rosi’s own move from Italy to England, to attend the photography program at the London College of Communication from 2013 to 2016, instigated a period of introspection about what it means to leave home and put down roots elsewhere. The feeling of being between cultures is at the heart of her practice.

“I was going back to my memories of Italy and looking back at images in family albums that would reconnect me with a sense of my identity,” she told me recently. Far from her familial networks, Rosi, who is still based in London, turned the lens on herself. “You use what you have at hand,” she noted with a wry smile.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

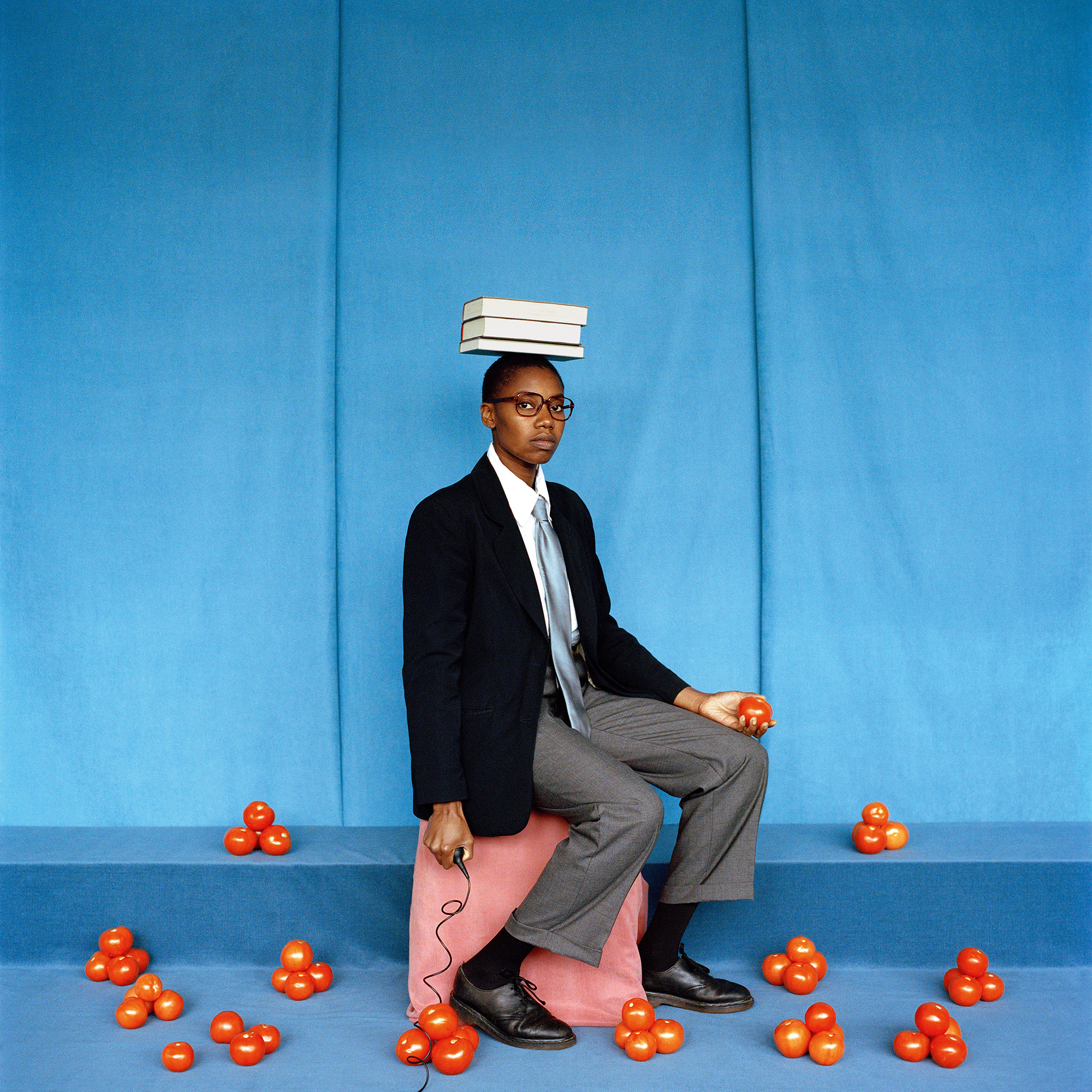

From the series Disintegrata (Disintegrated, 2024), the image Disintegrata con Foto di Famiglia (Disintegrated with Family Photo) shows Rosi standing between two wooden cabinets with framed photographs placed on them. The pictures—a woman in a wedding dress, family snapshots, a black-and-white studio portrait—suggest the ways vernacular photography has been used in the African diaspora as a means of documenting lives in transit. Her work also speaks to visual and oral modes of memory and transmission in family lineages. In Self-Portrait as My Father (2019), Rosi sits on a chair against a blue backdrop, balancing books on her head, wearing glasses and a formal shirt, tie, and trousers, like a clerk about to head to the office. On the ground next to her feet are tomatoes stacked in small pyramids. Here, Rosi steps into the metaphorical shoes of her father, whom she never met, filling in the gaps between his physical absence and the stories passed down about him by her mother. Though he arrived in Italy an educated man, Rosi said, “I know that when my father lived in Italy, he worked as a tomato picker. He ended up being part of the exploitation of migrants. This happened in the late 1980s, but it is also something that is still happening now.”

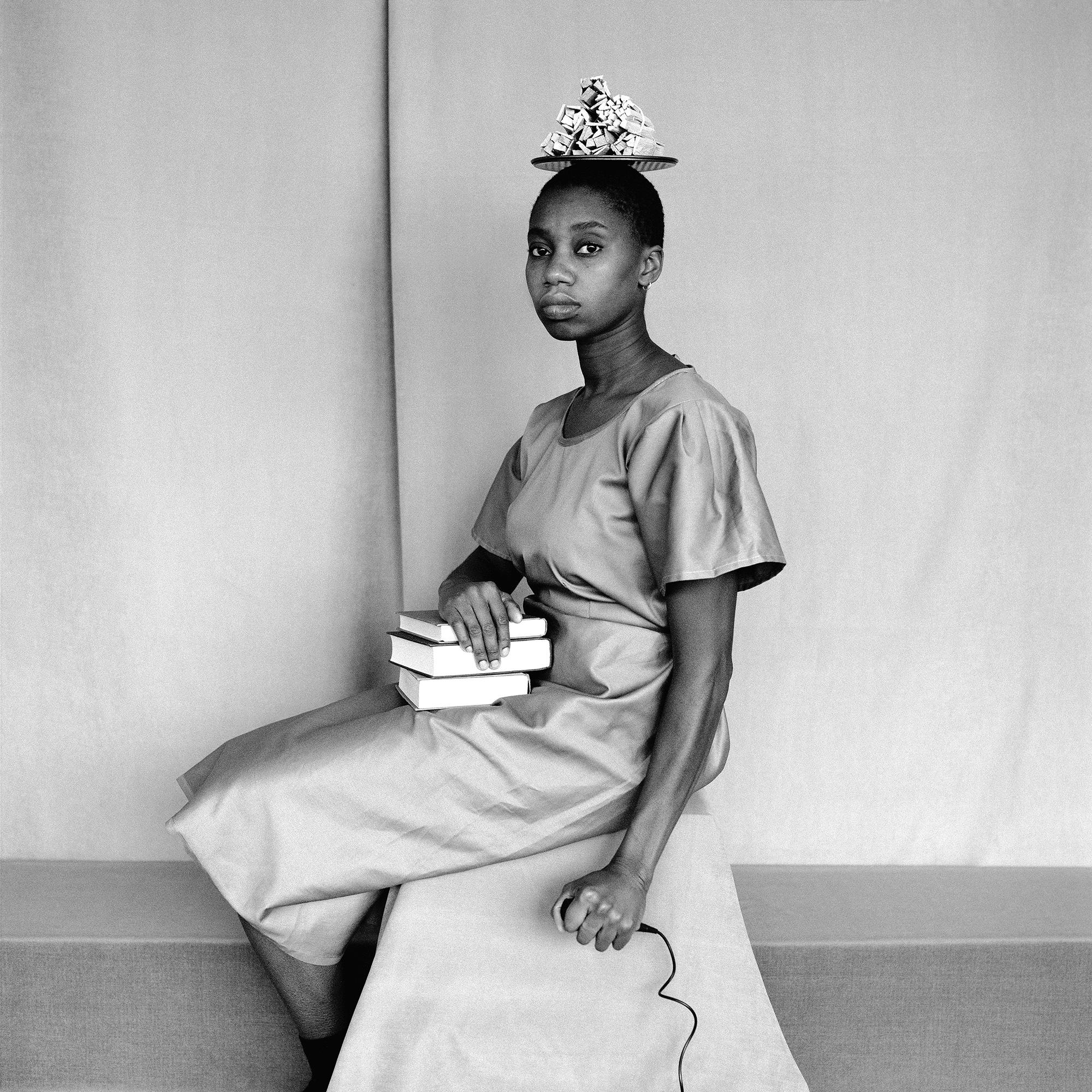

In Self-Portrait as My Mother in School Uniform (2019), Rosi carries toothpicks, reminiscences of the items her mother sold at roadsides and markets to passersby as a young trader in Togo, as her mother’s mother had before her. Styled in clothing similar to her mother’s school uniform, with books placed on her lap and her gaze fixed firmly on the viewer, Rosi inhabits the vulnerable yet entrepreneurial spirit of her mother as a young woman before motherhood. In another image, Self-Portrait as My Mother (2019), Rosi carries a radio on her head—a reference to highlife and Afro jazz but also a symbol of a deeply personal memory of her mother’s.

“The radio represents a moment when my mother was working for an Italian family. She overheard on the radio that a law would be passed that would legalize migrants present in Italian territory at that time, which enabled my parents to stay and live in Italy,” Rosi explained. Style and clothing, much of it sourced from secondhand shops, are key to Rosi’s work. In her inhabitations, the glasses or suit her father wore transcend their status as middle-class signifiers to become objects imbued with private meanings. Shutter release cables snake across the floor and lead to the hand of the artist, as if to show she is in complete control.

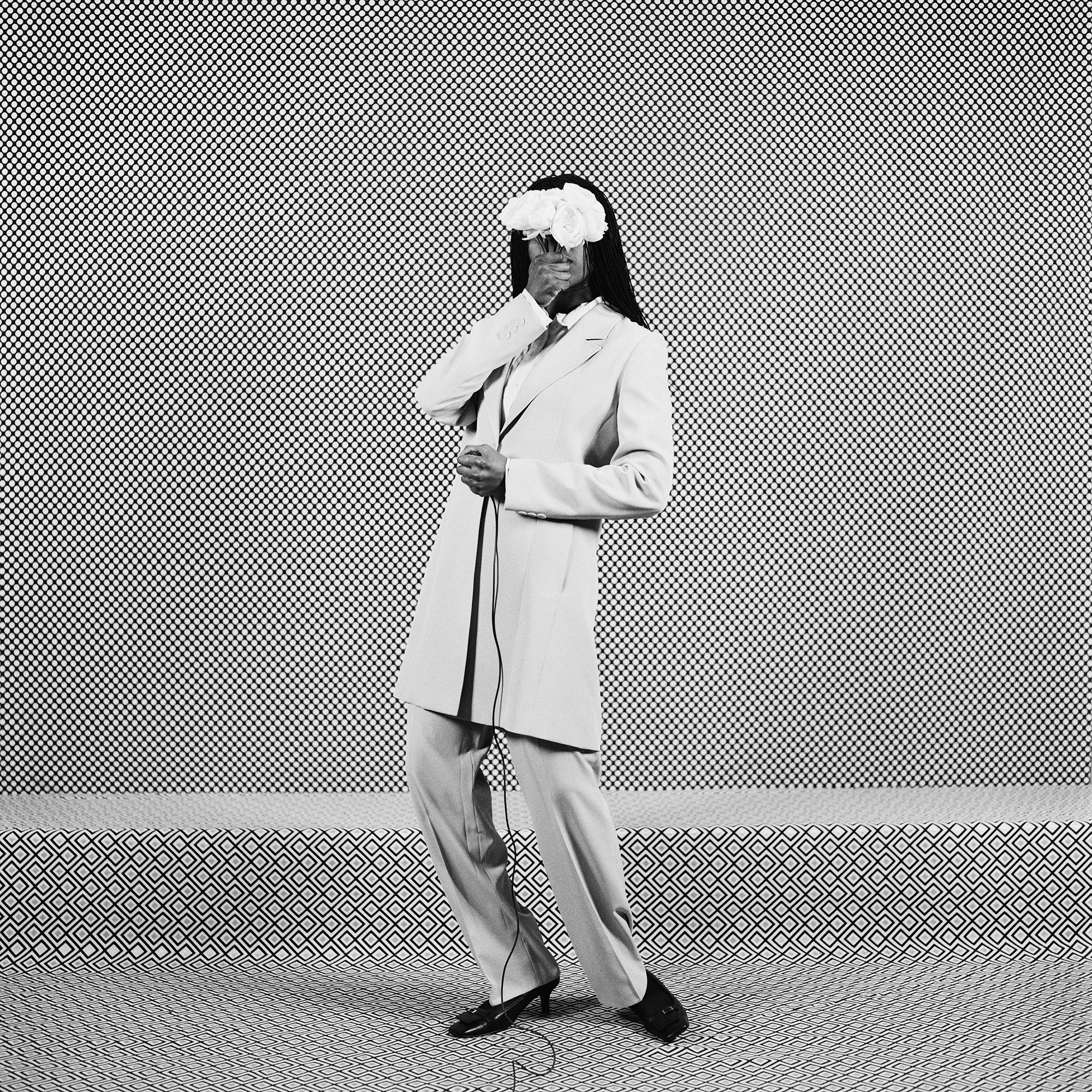

Rosi’s recent work is openly indebted to West African studio photographers such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, who helped visualize a kind of post-independence modernity. In one photograph, Disintegrata di Profilo (Disintegrated Profile, 2024), the artist, clad in a preppy blazer and khakis, poses with an Agfa-Gevaert book: an apparent reference to the legendary photographer James Barnor, who moved from London back to his native Ghana in 1970 to set up the first Agfa color-processing laboratory in the country. Rosi holds the book up to obscure her face, as if to resist the camera’s capacity to fix identity in place.

In bringing together the performative elements of self-portraiture and the commitment to preservation found in family albums, Rosi stages a different kind of performance, similar to the ways in which Samuel Fosso used his own body in the 2008 series African Spirits to perform and embody famous pan-African figures, including Patrice Lumumba and Kwame Nkrumah. Rather than reaching toward historical personages, Rosi emulates those who aren’t written about, the lives of immigrants trying to establish themselves in a new country in the face of economic precarity and cultural dislocation. Her images beautifully highlight tender, painful feelings of misrecognition and alienation, and the difficulties of starting anew.

All photographs courtesy Autograph APB, Collezione Maramotti, MAXXI and Bvlgari, and Jerwood Arts/ Photobooks

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”