Courtesy the artist and Danziger Gallery

Essays

The Afterimage of Joan Didion

Aside from portraits capturing her own nervy glamour, how might we consider the iconic writer through photography?

“My mind veers inflexibly toward the particular,” Joan Didion writes in her 1965 essay “On Morality.” When it comes to the concrete and specific, you might say there’s a continuum among her cohort (now mostly gone) of great American essayists. At one end, Susan Sontag’s epigrammatic judgments, with their relative lack of empirical texture. In the middle, Janet Malcolm’s fine attention to peculiarities of person or place. Then there is Didion, out along her own axis, where the essay is almost all detail. Sontag and Malcolm wrote extensively about photography. Didion, very little. But such is her mix of vision, exactitude, and atmospheric effect that her work seems more suited than that of others to sit alongside paintings, drawings, and photographs, with an eye toward making connections. In their introduction to the catalog of Joan Didion: What She Means—a recent exhibition at the Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles—the show’s curators, Hilton Als and Connie Butler, speak of Didion’s “acutely visual language.” What does that mean?

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy Left Bank Books

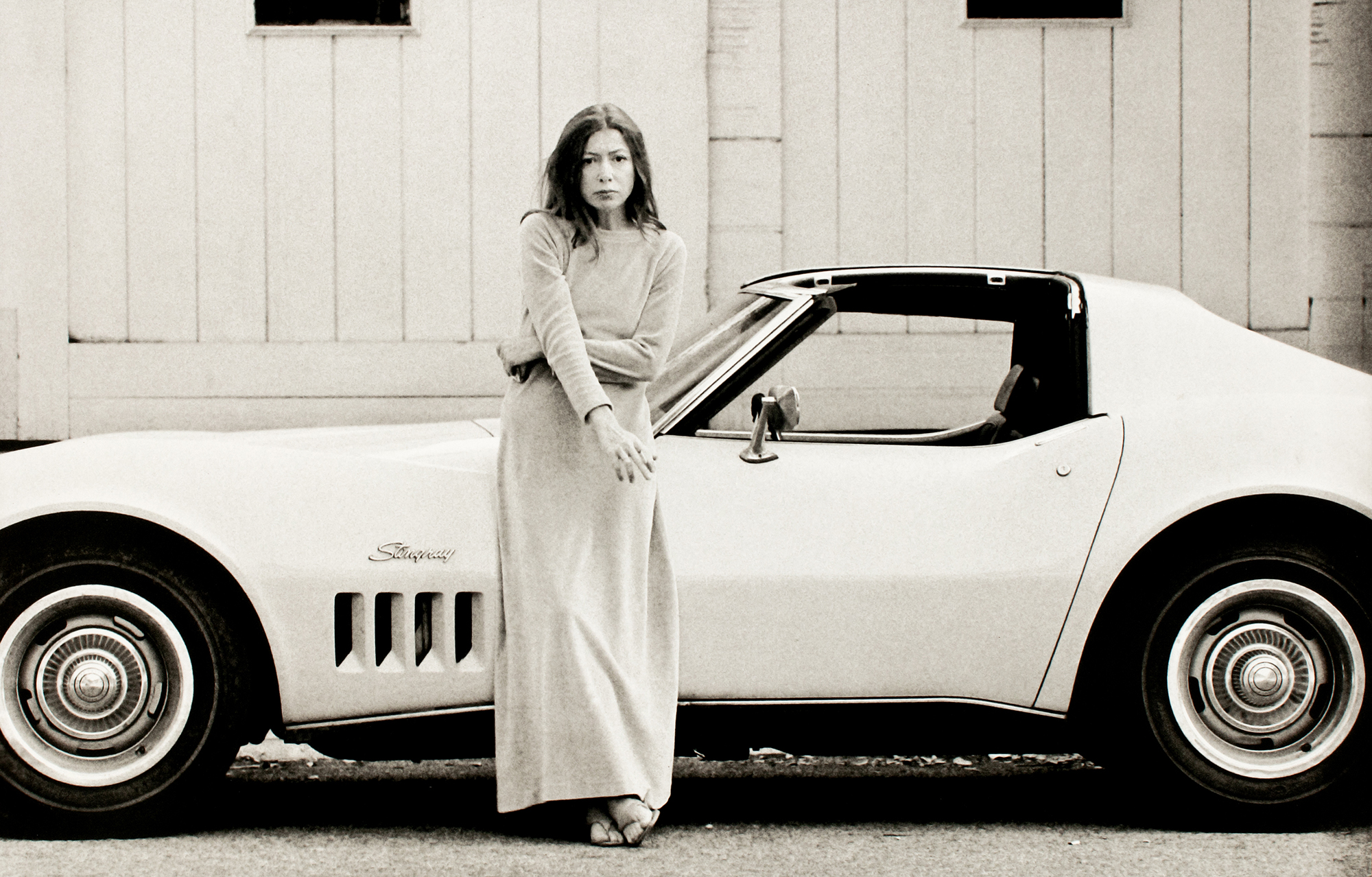

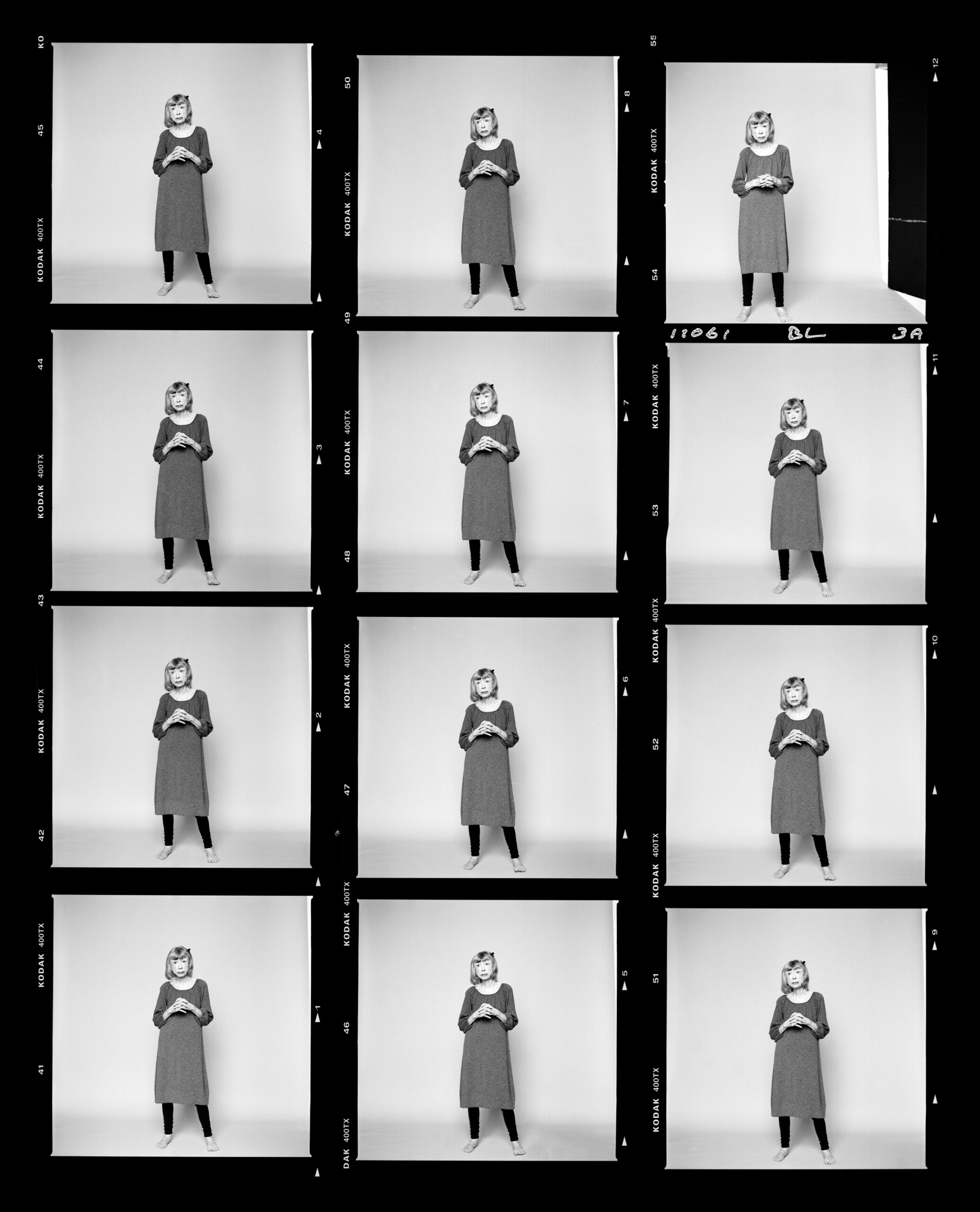

Als, a friend and literary peer of Didion’s, has previously put together exhibitions about James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, authors whose power and presence we may imagine we glimpse in photographs of them. But Didion is something else: a writer whose talismanic image—in life, and even more so since her death, in December 2021—is the object of feverish projection and surmise. No wonder, when we survey celebrated portraits of her. In 1996, she sat for Irving Penn, who seems to have noticed that in many photographs of Didion it’s her thin, bare arms that do the work of conveying brittle thought processes. Brigitte Lacombe photographed her in the same year as Penn: here, Didion vanishes into her turtleneck sweater but remains unmistakable thanks to hands and hair. A photographic ideal of the writer was already present in Julian Wasser’s 1968 studies of Didion leaning against her new Corvette Stingray. The ideal was still there in 2014 when Juergen Teller photographed her for a Céline advertising campaign: sunglasses, helmet of silver hair, birdlike (always this adjective) limbs inside simple clinging black.

Somehow, we have come to think of Didion as a writer whose photographic imago incarnates certain features of her prose, oversensitive but unsentimental, held together in the face of personal or cultural catastrophe—above all, cool. Since her death, there’s been an extraordinary poring over of period ephemera, including a Vogue photograph of her kitchen countertop in 1972, along with Didion’s stationery preferences and taste in glassware—these last thanks to online images from her estate sale. A curious way to commemorate a writer who, in 1979, while reviewing films by Woody Allen, despaired of a culture hooked on minor signifiers of self-image: “a subworld of people rigid with apprehension that they will die wearing the wrong sneaker.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

A composer, on the page, of indelible pictures, she was also highly suspicious of image making as such. One of the few pieces in which she writes directly about photographs is “Some Women,” a 1989 essay on Robert Mapplethorpe. It’s an oddly evasive text—the artist “struggling with illness” rather than dying of AIDS, his sexuality euphemized in the phrase “Rimbaud of the baths.” But she begins the essay with a frank reflection on time spent around photographers and their celebrity subjects when she worked at Vogue in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It seemed to the young Didion, part of whose job was to write captions for the magazine’s photo spreads, that photography was a matter of power and lies: “Success was understood to depend on the extent to which the subject conspired, tacitly, to be not ‘herself ’ but whoever and whatever it was that the photographer wanted to see in the lens.”

Aside from photographs capturing her own nervy glamour, what images come to mind when we think of Didion’s writings? Some snapshots from the more celebrated essays: The early-morning drinker in a Wilmington, Delaware, hotel bar, wearing a dirty crepe de chine wrapper, who says: “That woman Estelle is partly the reason why George Sharp and I are separated today.” A Volkswagen in flames on the freeway, and the murdering wife in her too-fancy courtroom outfit. A three-year-old on acid.

Courtesy the artist and Lacombe, Inc.

American mundanity, obscenity. “It so happens that if you’re a writer the extremes show up,” Didion tells us. In the Hammer Museum catalog, a Warhol electric chair occupies a left-hand page; on the right, photographs by William Eggleston of a Spanish-style veranda, an empty swimming pool in sunlight. The tensions in Didion’s writing are usually subtler than this juxtaposition suggests. As an analogue, consider a Garry Winogrand photograph, taken in Beverly Hills, of a young woman in a miniskirt decorated with hearts. Is the faceless man beside her a threat, in his leather jacket and knee-high boots? A species of overlit dread pervades much of Didion’s work of the 1960s, even more so the retrospective essays of the decade following. Another name for this feeling is California.

A composer, on the page, of indelible pictures, Didion was also highly suspicious of image making.

According to Als, an aspect of Didion’s genius was “to make language out of the landscape she knew.” There are photographs in the book and exhibition that stand somewhat literally for essays in which she draws on Californian history, fable, contemporary, or horror. In her 1970 essay about visiting the Hoover Dam, and again in “Holy Water” (1977), Didion conjures an arid land in which water is money, power, myth, and also metaphor for hope, movement, loss. A 1928 photograph of Mount Tamalpais by Alma Ruth Lavenson and Edward Weston’s Badwater, Death Valley from 1938 summon the geocultural bedrock of Didion’s early life and much of her work about the West. Also in the book and exhibition are snapshots of a heavily pregnant Sharon Tate in 1969, shortly before she was murdered. Mythic land, end-of-the-1960s nightmare: direct illustrations from these histories don’t quite capture the peculiar, drifting abstraction that can shadow Didion’s fidelity to fact.

Courtesy the artist and J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles

Courtesy the Estate of Garry Winogrand and Fraenkel Gallery

Here, for instance, is a passage from The White Album on the mood in Los Angeles during the summer leading up to the Manson murders: “A demented and seductive vortical tension was building in the community. The jitters were setting in.” What is the photographic correlative for the vortex, for the jitters? It’s not to be found in Californian landscapes, austere or picturesque, or in the glassy midday version of street photography that LA makes possible. It’s more visible, I think, in the streaked darkness of the book’s 1943 Jack Delano photograph of the city’s rail yard at night, or in the serial vacancies of Ed Ruscha’s conceptual noir: blurred cars on Santa Monica Boulevard, repeated-with-a-difference gas stations, low-rise apartments, palm trees. The auction of items from Didion’s estate reveals that she owned several of Ruscha’s books from the 1960s and 1970s. In 2005, for the catalog of his contribution to the Venice Biennale, she wrote a short essay in which she describes the peculiar atmosphere of approaching the city from LAX: “Which streets they were did not matter. What did matter were the hard industrial angles, the gas stations and the strip malls and the two-story apartment buildings with the outdoor stairways and the covered walkways upstairs, the very stuff that said Los Angeles to me, all swimming in the lurid light that comes there in the western sky for a few hours before the sun drops below the horizon and the known world goes dark.”

There’s something inordinate in such passages, exceeding Didion’s attachment to the concrete or, as she sometimes put it, her strict inability to think in the abstract. (As a student at Berkeley, she recalled, she tried hard to consider the Hegelian dialectic but was apt to be distracted by petals from a flowering pear tree outside her window.) The quality I’m trying to catch here is not exactly abstract or conceptual in ways we might speak of those things in modern or contemporary art. But it belongs to a region of the mind, perhaps of the world, that won’t easily give itself up to word or image. An obscurity of scene, mood, or atmosphere that is maybe best captured, among the illustrations in Joan Didion: What She Means, by a Diane Arbus photograph, from 1960, of a New Jersey drive-in movie theater. Is that the sun or moon on screen, clouds scudding across? Points of light in the dark foreground, desires hidden in automobile interiors. (See also: the lowering sky, in three stills from Stagecoach [1939], behind John Wayne, whom the young Didion adored.)

In “Why I Write,” a lecture delivered in 1975 and published the following year in the New York Times, Didion states, “The arrangement of the words matters, and the arrangement you want can be found in the picture in your mind. The picture dictates the arrangement.” It’s easy to imagine that she simply intends the affixing of a tracery of style to observed or recalled reality. In fact, it’s not at all clear what Didion means by “the picture.” Despite its precision, the prose is not a type of documentary, analogous to photography. (No more, of course, is documentary photography only documentary.) Instead, she writes to diagnose and to divine—like the greatest photographers, straight or conceptual, she is also searching for something that cannot be seen.

Edward Weston, Badwater, Death Valley, 1938

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”