Photobooks

The Delight and Absurdity of Domestic Photography

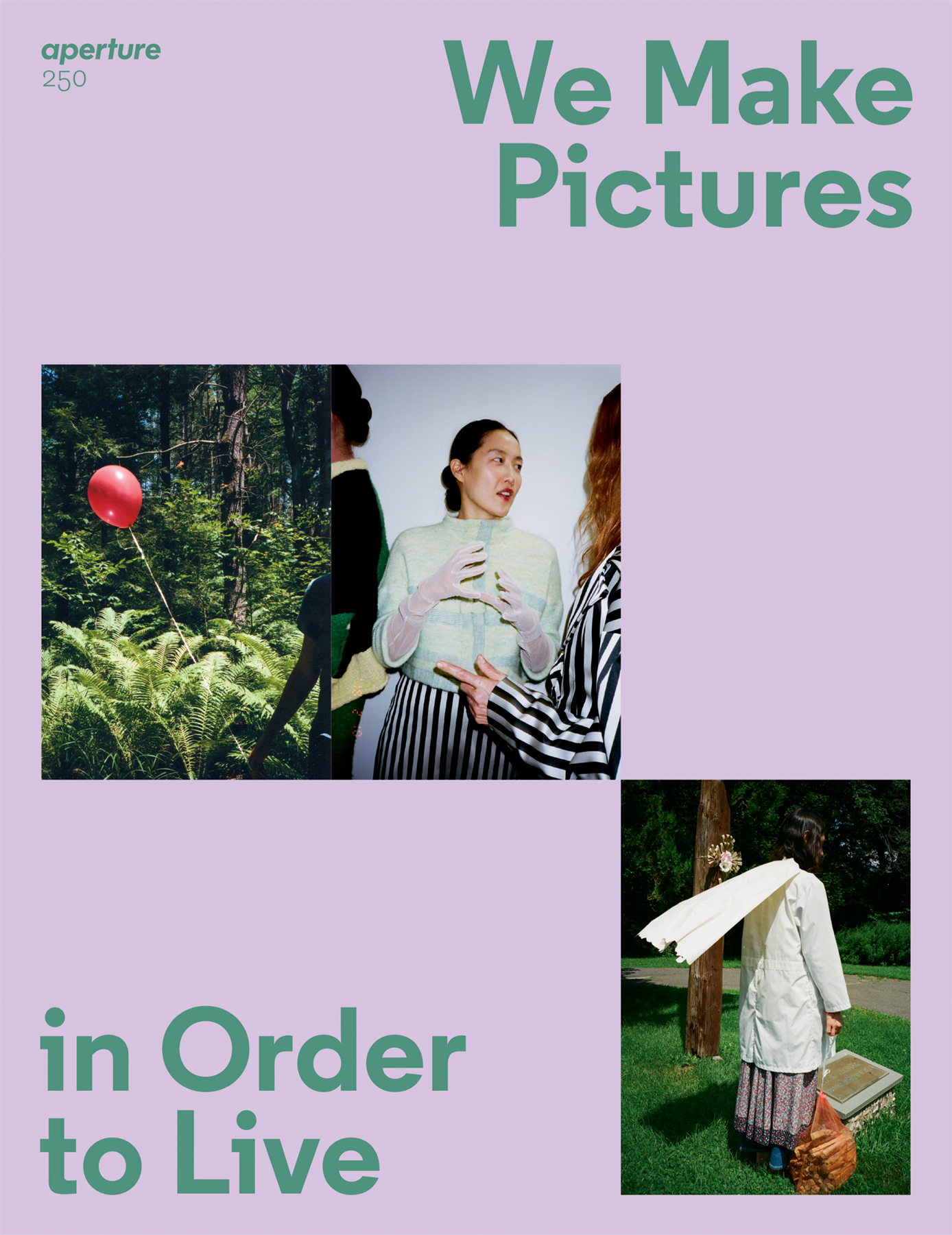

A trio of photobooks about domestic life reveals the home as a site of humor, performance, and self-fulfillment.

Throughout the pandemic, the popular conception of home became a place of unrelenting monotony—a site of confinement, despair, potentially even breakdown. Creativity was stifled when stuck in one’s living room. It was impossible to maintain professional output while sharing a space with one’s children. To many women, this new obsession with the inside, the domestic, was both frustrating and amusing. Home was now a space confining both sexes. And yet, female artists have long centered home as a site for probing discussions and creative explorations. The resultant works often deal with the themes that contributed to women’s very presence at home in the first place: sexism, pay disparity, childcare inequality, patriarchal conditioning and control.

The domestic and, in turn, the family have been popular topics within the history of photography, as well as the subject of various notable exhibitions—for example, Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, in 1991, and Who’s Looking at the Family? at London’s Barbican, in 1994. Many of these were curated, in part, to redress the lack of female representation within museum shows, a fact that makes the included works’ commentary on the narrowness of women’s opportunities and freedoms only more poignant. Women photographers were in the museum, and yet, somehow, still at home, in their place.

In the catalog for Pleasures and Terrors, which featured Ellen Brooks, Jo Ann Callis, Doug DuBois, William Eggleston, Cindy Sherman, Sage Sohier, and Carrie Mae Weems, among others, the curator, Peter Galassi, wrote that artists “began to photograph at home not because it was important, in the sense that political issues are important, but because it was there—the one place that is easier to get to than the street.” The comment likely amused some female artists at the time but now reads as starkly unperceptive, if not blind to varied motivations in creative experience. This lack is especially obvious when one surveys just a few of the many new books and photographic projects dealing with home and domesticity: Talia Chetrit’s Joke (MACK, 2022), Csilla Klenyánszki’s Pillars of Home (Self-published, 2019), and Kuba Ryniewicz’s Daily Weeding (Note Note Éditions, 2021).

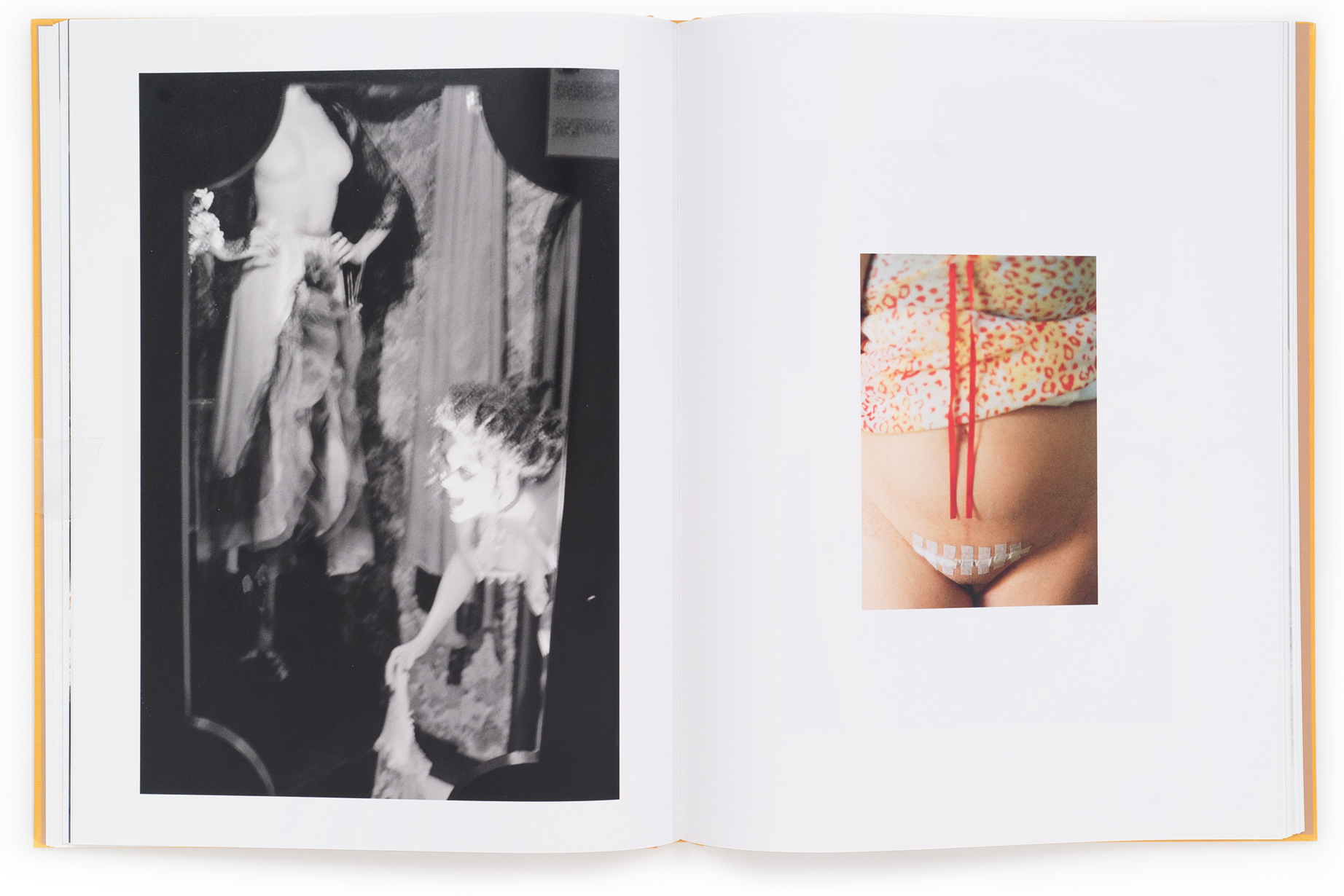

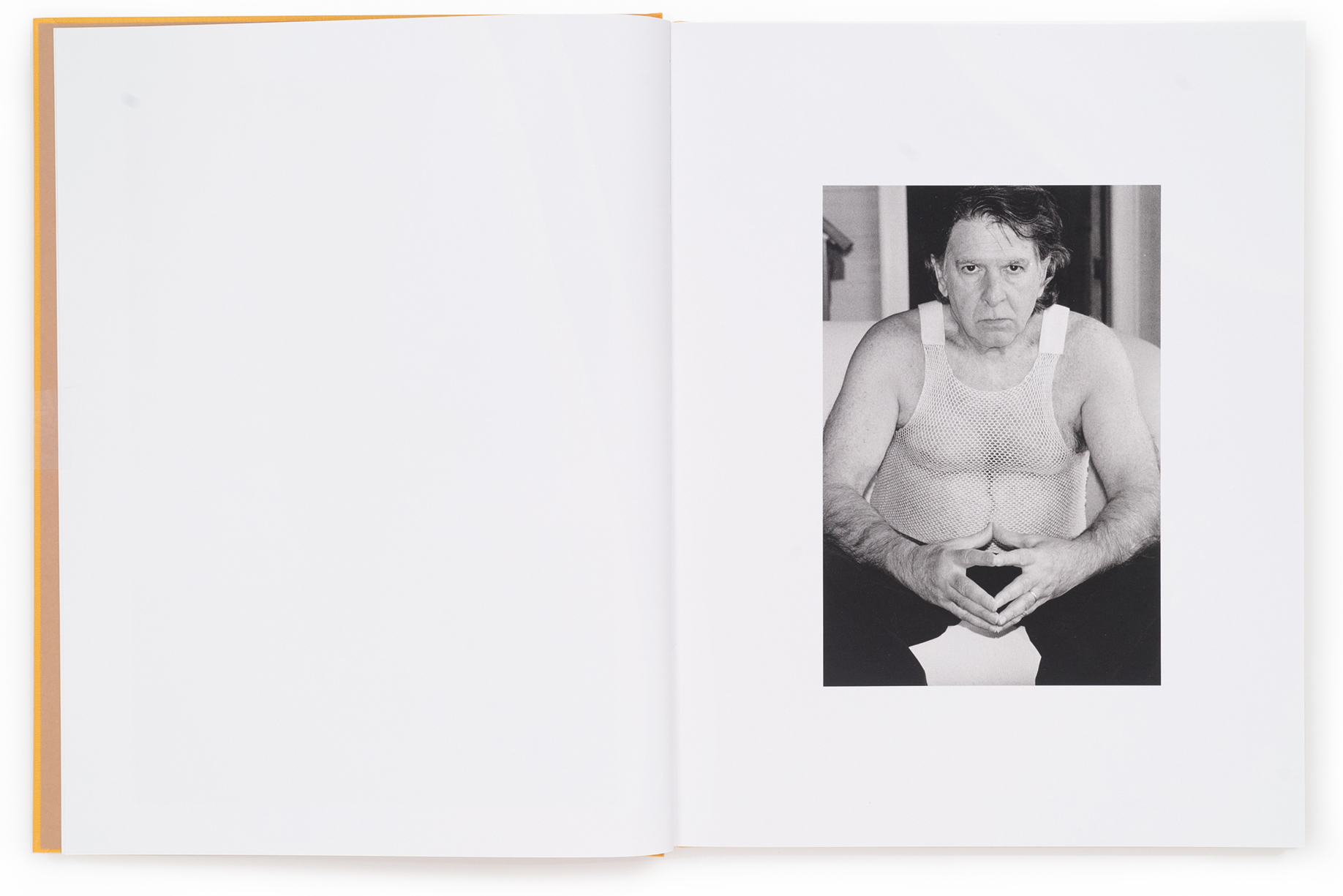

These image makers photograph home both because it is “there” (and was “there” more obviously than ever during the pandemic) and because it is “political” and “important,” to use Galassi’s aspirational words. Both Chetrit and Klenyánszki infer that the very fact of their both, as women artists and mothers, being “there” (at home, caring for babies) is, in itself, fruitful territory for the exploration of some of the most troublesome and limiting divisions, and habits of thinking, within society. Who is a mother? What behaviors make her good? What subjugations should she tolerate? What should she keep of herself? Can she be sexual? Can she be an artist? Who is a father figure? Is he at home too? What is home? In Chetrit’s pictures especially, the send-up of familial tropes and domestic scenes, with humor and light irony, is enjoyable—an older man sits, legs spread, his chest hair showing through his mesh undershirt; a young father, wearing a dress with layers of yellow tulle, stands next to his baby; disembodied mannequin limbs appear on the page before a close-up of a caesarean scar.

The works made me think of Jo Spence and Patricia Holland’s book, Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography (1991), in which Spence asks, “The family album: what does it contain? What lies beyond the symbolic images of special events, occasions, celebrations, ‘success’—particular weddings, the new baby, holidays, the ‘happy family’?” Spence offers, “Perhaps, superficially, family albums tell us more about the accepted ways of picture-making, or what was considered appropriate at any historical time, than they do about the particular family represented?” Chetrit’s goal seems to be to revile “appropriateness,” to thumb a nose at the serenity and wholesomeness that are expected in depictions of mothers, families, and children.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

On the first page, we see a baby, naked except for a diaper, playing in front of a shelf of children’s books (Madeline and the Cats of Rome, Mr. Tiger Goes Wild). In front of it, a single adult leg bisects the image, masking half the child: the leg wears a shiny black thigh-high boot. The combination of the supposedly pure and the latently erotic is designed to disarm, to nod to the many often irreconcilable fetishes that surround women—mother, sex object, Madonna, whore. Chetrit’s picture is also funny, as a visual. I laughed when I saw it. Projects about home often deal with pungent dichotomies: prosperity versus compromise, safety versus violence. Chetrit composes such juxtapositions with refreshing lightness, refusing to be solemn, sentimental. The book’s title here—Joke—is perfect. She finds the traditional stereotypes of family ridiculous. She will not dignify them with anger. Her humor is always more sardonic than slapstick, a little knowing, a little cool. The inclusion of high fashion in the images (Balenciaga jeans, a micro Chanel handbag) is unsurprising—Chetrit has photographed for various brands, such as Acne Studios and Celine—but contributes to the sense of insolence and chilliness. Such inclusions give the work an impenetrability, which in itself refutes the idealized vision of mothers as open, kind, soft, welcoming.

There is also wit in Klenyánszki’s Pillars of Home, which makes a physical manifestation of the concept of juggling, a buzzword in so many conversations about domesticity and motherhood. The small-scale book features photographs of sculptures built from household objects during the photographer’s baby’s nap time. The statues are precarious: a baguette is about to snap under the weight of an umbrella, a pile of oranges is ready to tumble down. In Pillars of Home, Klenyánszki writes that, should the installation collapse, not only will the “existence of the image” be “in danger” but also “the noise of the fallen objects might awaken the sleeping baby, which puts an end to the working session.” The book is a comment on limited freedom—on the way a child restricts options and hampers work, the way the family can smother the individual.

Looking at each sculpture, one imagines the forthcoming crash, a wail from an adjacent room, the rush of feet toward the cry as the objects shatter or roll, the vibrations spreading across the room. The best images are the ones where the fall seems certain and particularly violent: a vase of flowers balances on an open door, a pair of splayed scissors sits vertically on top of the blooms. One knows it will come down. There is a shakiness and vulnerability that seems in keeping with the precariousness of our times. Everything we build, the supposed securities of home and family, can be swept away in a moment by external factors: pandemic, death, war, climate change, the cruelty and inexplicability of other people’s choices.

These books speak of an age of juxtapositions, dissonance, oddness—of uncanniness, within the home as everywhere.

Klenyánszki’s book nods to the arguable irrationality of bringing a child into a collapsing world. One of the project’s weaknesses—repetitiveness—is also its strength. By the middle of the book, the photographs, and sculptures, start to blend; one tires. It infers the relentlessness of child-rearing, of life in a small apartment, and, in turn, the relentlessness of worry, instability, crisis.

The monotony of crisis also underpins Ryniewicz’s Daily Weeding, which was made during lockdown, and features images of friends and neighbors hanging out near high-rise tower blocks, gardening, or nurturing swollen pregnant stomachs. An accompanying text by Olivia Laing refers to “love in a tiny space.” She wonders, “Could it still feel free?”

Writing in the introduction to Family Snaps, Holland argues that “making and preserving a family snapshot is an act of faith in the future.” What all three books, but especially Joke and Pillars of Home, present is the family snapshot when that faith in the future is shaken, no longer rational or appropriate. They speak of an age of juxtapositions, dissonance, oddness—of uncanniness, within the home as everywhere. If the function of the family photograph has typically been to serve as propaganda for traditional systems, for conformity and the illusion of bliss, these works seek to unsettle, to gently mock. But they are not simplistic manifestos. All three books retain the deeply personal aspects, along with a sense of quotidian flow, that make domestic photography interesting. They are as much records of ambivalence as of anger, of acceptance punctuated by occasional flashes of thirst for self-fulfillment, authorship, and—the perpetual great threat to home and family—more.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live,” in The PhotoBook Review.