Portfolios

The Photographer Who Sees with Her Fingertips

Aspen Mays makes photographs without a camera and in total darkness, conjuring images both intimate and otherworldly.

Like many analog photographers, Aspen Mays makes images in a darkroom. But unlike most of them, she doesn’t use a camera and film. She creates her photograms in complete darkness, without even the red glow of the safelight. For hours, she works with eyes unseeing and often closed, guided by muscle memory, touch, and the sound of dripping water.

In the dark, Mays reaches for objects she arranged in the light. Her fingers find the taped lines on the table directing her to materials. She creases photographic paper, invents celestial patterns with a hole punch, and layers and removes tape to form sunbursts and spiderwebs.

“I’ve always been interested in uniqueness,” Mays said, “working with base materials that rely on hand processes.” Such an embodied approach requires endurance, which in its solitary production sometimes drifts toward entropy. “I’m taking patterns to such repeated iterative extremes that they often start to fall apart.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

We typically think about craft in photography as aligned with technical precision, repeatability, and visual fidelity, but Mays’s images defy such virtues. The hand is privileged over the eye so that every photogram shows traces of manual manipulation and darkroom chance—a pinhole, a light leak. Her work invites the viewer into a story of its making. The intricate, imperfect human elements behind her analog image creation counter our greedy consumption of ever-optimized digital photographs.

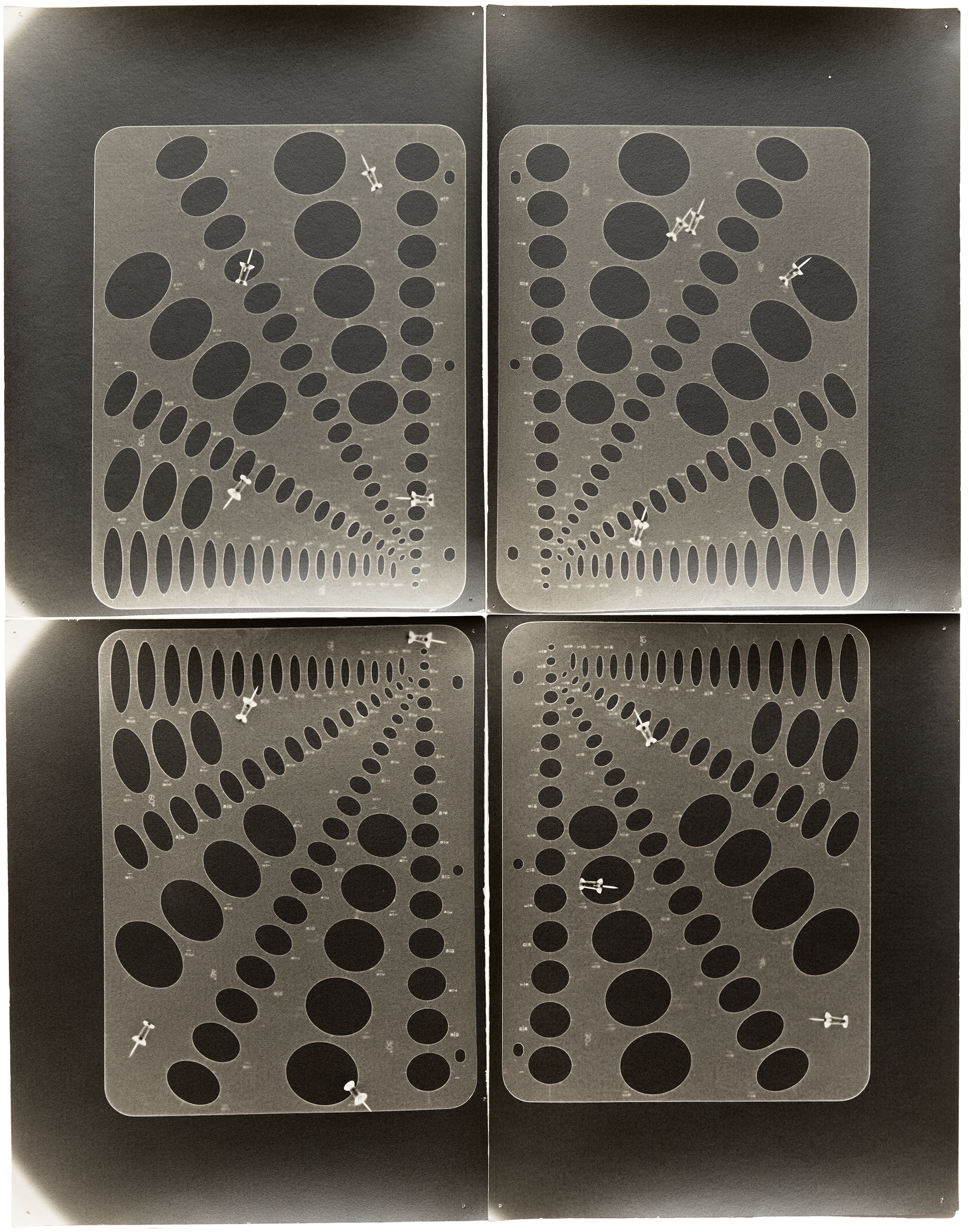

Mays was raised in Charleston, South Carolina, and now lives in the Bay Area. Her father was an architect. Before he switched to digital design tools, his home drafting table was a source of endless fascination to Mays, littered as it was with rulers, erasers, pencils, and templates to make almost any conceivable shape. For a recent series produced at the Rauschenberg Residency on Florida’s Captiva Island, Mays used templates inherited from her father and grandfather, who was also an architect. “I love the uniformity and how they standardize space,” she said, recalling how her grandfather’s and father’s hands had traced lines with these tools.

One photogram, Blind Pass (2025), captures a semitranslucent template, which was repeatedly exposed on a folded sheet of paper. Mays arranged the template so that the lacy rows of diminishing ovals converge. The composition flickers between an arrangement of ordinary objects and something more galactic, like a supernova.

Cosmic themes thread through her work, connecting acts of the hands with acts of the heavens. For the series Punched out stars (2011), Mays used a perforator to riddle gelatin-silver prints rejected from the University of Chile’s Astronomical Observatory archive, subtracting every visible star. The result is clusters of enigmatic white circles and fabric-like creases. “The cosmic is a totally dizzying thing to confront—the smallness of your experience or the vastness of the universe,” she said. “It’s a way for me to think through the conundrum of experience.”

Tengallon Sunflower (2016) is a more personal, earthbound project. Two bandanas are at the heart of the photogram series: a starburst-patterned textile inherited from her great-grandmother and an indigo-and-white cloth owned by Georgia O’Keeffe. Mays pricked out the starburst pattern with a pin, marring the cotton rag gelatin-silver paper, then dyed the paper using indigo and other blues that resemble cyanotypes and diazo blue-prints.

Mays likes the intimacy of a bandana, how the square of fabric was designed to be knotted ever so snugly around the neck. “Sense memory feels antithetical to photography, which, of course, privileges a visual kind of memory,” she said. Her work is a meditation on the nature of touch. Not in caresses or gestures that require an artist’s hand—folding, pinning, punching, dyeing—but in the way a stray fingerprint or scratch flouts photographic mores and disrupts a pristine surface. Her transgressions in the dark remake the ordinary into something strange, transcendent, and beautifully otherwise.

All works courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”