Interviews

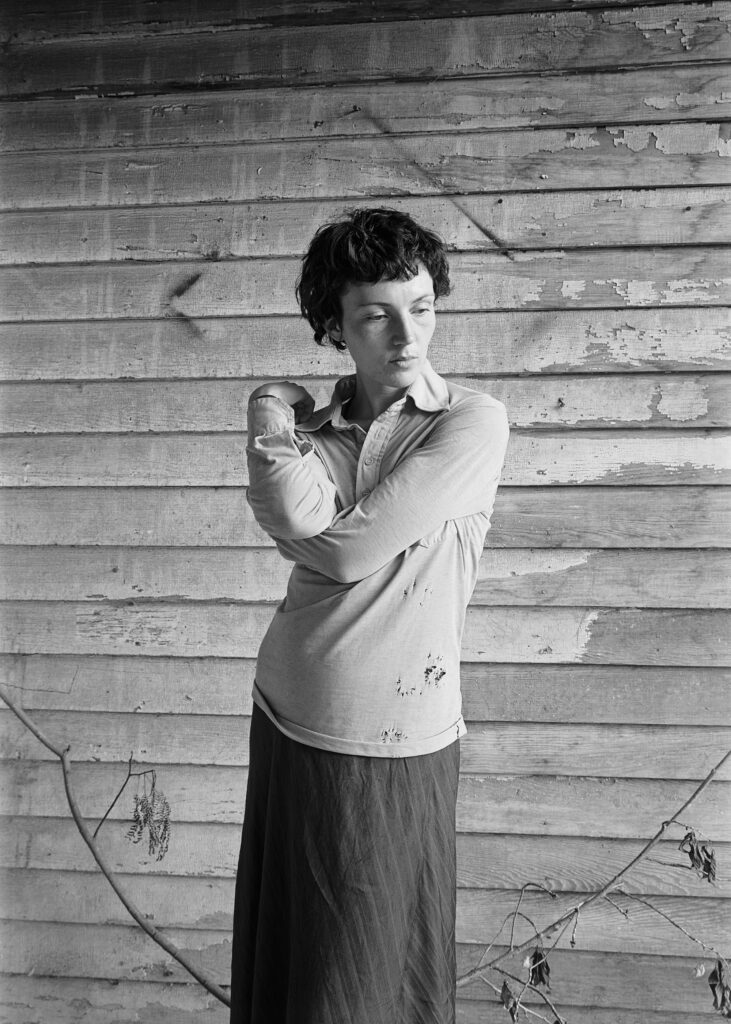

The Photographers Who Built an “Army of Lovers” through Protest and Celebration

During the Stonewall Protests in 2020, activists organized to speak out against violence and homophobia, galvanizing the community in the fight for Black trans lives.

In June 2020, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Over the following year, protests in the form of marches, voguing balls, or vigils brought together thousands of people across communities and social movements to gather in solidarity, resistance, and communion.

Bringing together works from twenty-four photographers, Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation (Aperture, 2022) is a powerful and celebratory visual record of New York City’s contemporary activist movement. Below, read a conversation from the volume between Raquel Willis and Qween Jean.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Raquel Willis: Could you place us in the environment of young Qween Jean, and the journey that laid the foundation for you to become so invested in Black Trans Liberation?

Qween Jean: To set the world for young Qween is difficult. She faced a lot of issues with self-worth, value, and wanting to be- long, a lot of which was tied to faith and spirituality. My household was rooted in faith and discipline, and focused on preservation and appearance. How are we viewed as a family? Will we make our parents proud? But in the end, those ideals and visions didn’t really include me, all of me, the full parts of myself. I thought, If this is family, I don’t want it. Because I can’t be myself here, I can’t dress the way that I want here. I have to constantly conform myself and shift, code-switch into this being, into this boy.

Willis: I resonate so much with that feeling of not belonging and not having a space of salvation. Church is often a safe haven for Black families and communities, but I wasn’t in a “Black church,” I was in a Catholic church. So as a Black family in the South, there were multiple layers of feeling we’re not where we’re supposed to be. And I’m not who I’m supposed to be. As a kid, I felt all these questions of, What is the rulebook? What is this script that seemingly works for everyone else that I just cannot get the lines and blocking down for? I think the points that hurt the most were when I knew that I was queer or that I was gender nonconforming, and I really wanted to own it, but I didn’t because I wanted to save face for my family and for all the people that I was supposed to represent. But I was never going to stay silent. I was silent for too long. It just got to a point in high school where I knew, this is the point of no return, honey.

Jean: High school was a big turning point for me as well. It is when I started my physical journey into femininity, into womanness, into Qween. And honestly, if I didn’t do something, it would have been a thorn in my side. The point of no return: I’m ooout! And I’m proud!

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Willis: Exactly. I’m out. So what are we gonna do about it now? Because I’ve had to navigate and strategize for my own survival up until this point, so you figure out the rest, because I’m not going to live with this secret anymore.

Jean: Before I started reading stories of Black queerness, seeing Black queer elders, seeing other young trans women, I spent a lot of years in turmoil, angry and conflicted. The first time I saw a Black trans woman, I was in a flea market with my mother. There was definitely a disdain for her presence from the other Southern Black women. But for me, there was complete eruption of joy to see myself, essentially. Moments like this have inspired me to ensure that young people don’t feel ostracized or less than because they’re different, because they’re heavyset, because they’re dark-skinned, because they’re disabled, because they love Sailor Moon, for any reason.

Willis: Well, you are the evangelist, honey. Every time I see you, I hear you speak, I hear you sing, there is a testimony. What is that testimony that led you to activism and to the Stonewall Protests?

Jean: Wow, yes! It is a testimony. Personally, I believe that God doesn’t give me the spirit of fear, so why should I be afraid? There have been so many things in my life that I have navigated, dealt with, am still struggling with, that didn’t kill me. And so why should I not sing? Why should I not fight? I always come back to the phrase “come as you are.” There’s such power in that idea: to come with your experience, your struggles, your burdens, all the trespasses that have been made against you, to show up and still have faith and to still know, without a shadow of a doubt, that you will win, that you will persevere. I, and all queer people, experience moments where we feel we are alone or will no longer be accepted, that we won’t be loved, that we won’t make it. And I’m here to say we are. And we will.

Willis: And we have!

Jean: And we have. Because the reality is, we’ve always been here. We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social justice movement. We’ve existed.

Courtesy the artist

Willis: I think about how depleted so many of us were in June 2020 after the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and then of course the overlooked Black trans murders: our brother Tony McDade in Tallahassee by police, Nina Pop and Monika Diamond, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells and Riah Milton. We were depleted but still managed to organize and to show up for the first Brooklyn Liberation march on June 14, 2020, which became one of the largest marches for Black trans lives in history.

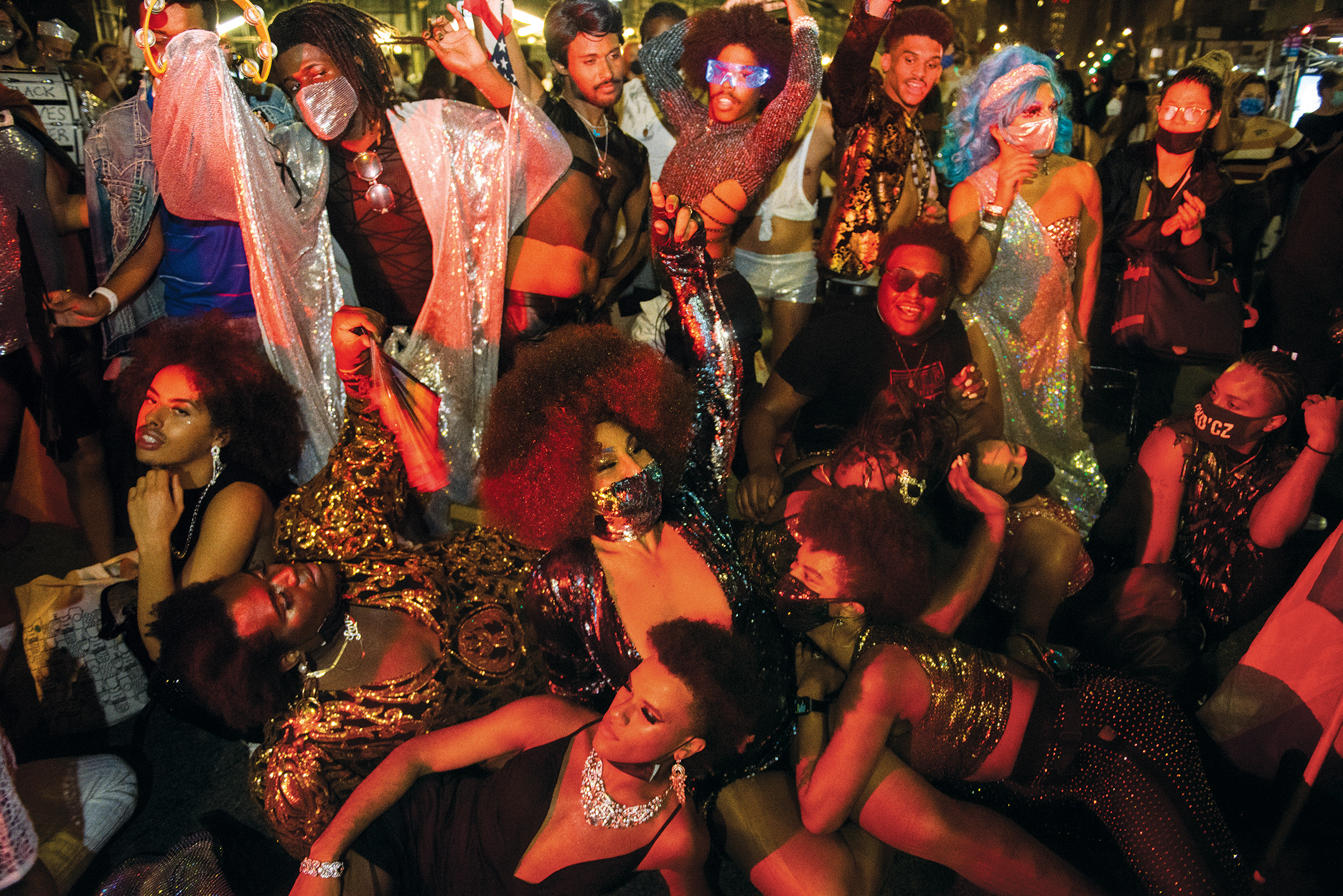

Jean: The Brooklyn Liberation march in 2020 has been one of the most powerful moments in my entire life. I think that people are going to talk about that day for the rest of eternity, truly. Because we saw so many people come out who were depleted, who felt like, Is this ever going to end? The violence is just not stopping. But there was so much love and joy in that space. It truly was an alternate reality. And that was liberation. It was a space of liberation, where people felt seen, held, celebrated. We were with our living deities. What a gift.

We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social justice movement. We’ve existed.

Willis: Liberation is so speculative and can feel impossible. You’re literally writing fiction in your head when you’re thinking about liberation. But that day when upwards of twenty thousand folks came out—a whole congregation of folks who weren’t necessarily Black, who weren’t necessarily trans—it felt possible.

Jean: I will never forget being able to turn any direction and see so many beautiful kinsmen, kin sisters, kin siblings who had also come out to receive that blessing. So many people that I admire and look up to testified that day about love, about community, about taking pride in the self, about standing up to your enemy, to your oppressor, and saying to them, “You will not win.” It was a benediction for me. It gave me marching orders and gave me direction. I recited the benediction every chance I could, because it was a way for me to connect back to that moment of liberation.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Willis: It’s divine inspiration. Whenever it feels impossible for us to reach liberation, I have that moment, that day, to look back on. With the Stonewall Protests, you have so many moments to look back on from that year because you gathered every week after Brooklyn Liberation. What is that like for you, to be living with those glimpses? And what does that make you hungry for now?

Jean: At the Stonewall Protests, we came out to seek truth: emotional truth, the overwhelming political truth that exists within our world, and personal truth. And we needed space. Week after week in 2020, more of our Black trans siblings were being killed, and we needed a way to heal, to escape and gather, to scream it out, to march it out, to rejoice, to join in fellowship and to dance. And to truly be connected and fortified. It was like church in so many ways.

Willis: And a ball. It was everything at one time.

Jean: The community was so powerful. We were ultimately coined an army of lovers. People from all walks of life, from all backgrounds, all ages, all intersections of race and culture and religion. We held space, and we gave reverence, and we all understood the role that we had to play in that moment. We had to combat and to speak out against injustice, the ongoing racism, transphobic violence, transphobia, homophobia that exists in all of the subcultures that we know, that we come from, and all the communities that we shy away from, where we don’t feel safe, where we don’t feel accepted. This was a space where we could belong. And I want that to be a permanent space. I want to create a place of worship for queer people, for trans and nonbinary-identified folks. We deserve a trans choir! So many of our people have an anointed gift. Young queer people, we need a space to just have, to hold, to call our own. That is something that I know in my destiny has to happen. In so many ways, the Stonewall Protests was the church experience that I wish I could have had as a child. I prayed that I could have met up with community once a week in my Sunday best and come with a spirit and a fervor for truth.

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation

45.00

$45.00Add to cart

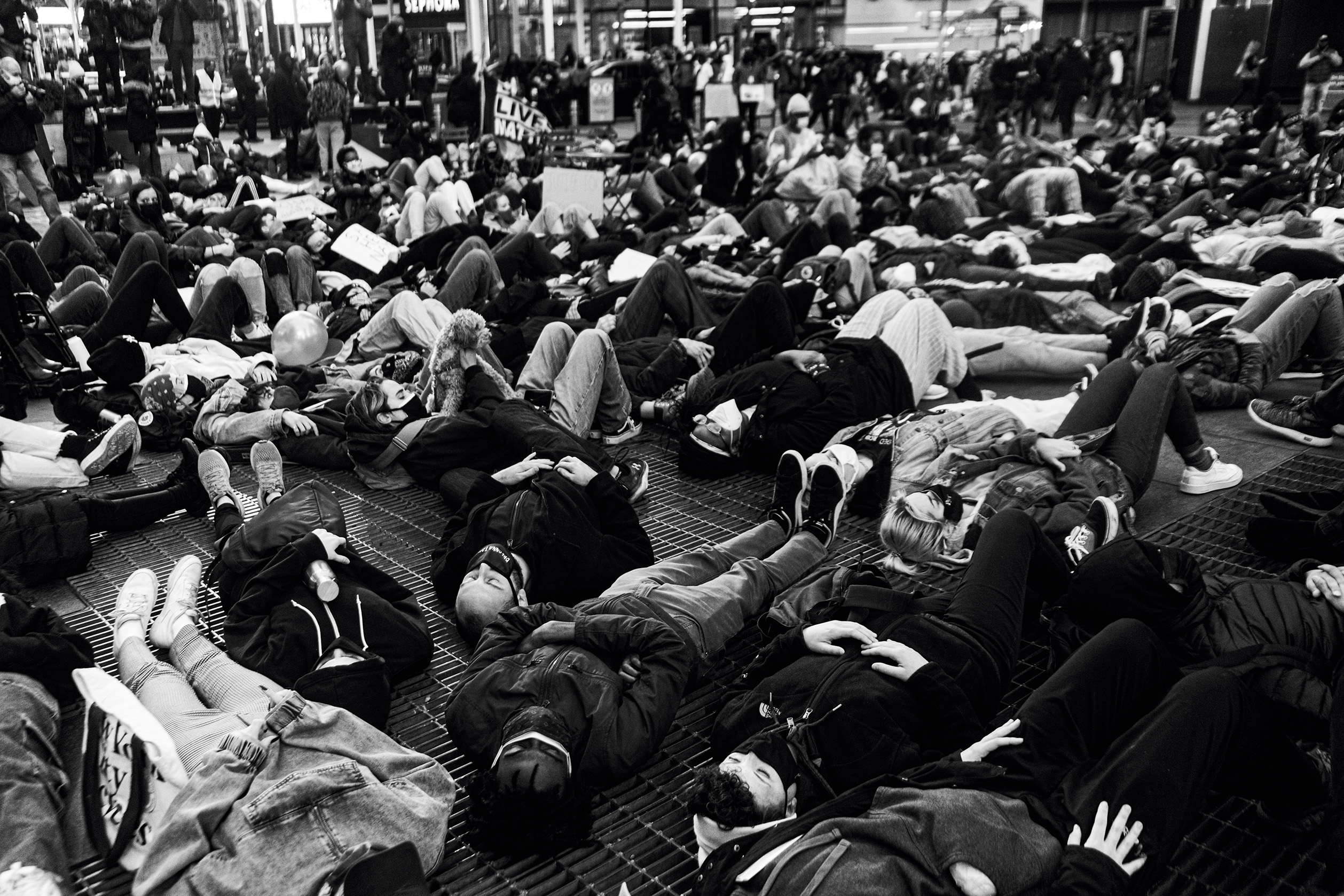

Willis: I love that you have documentation of what was happening from week to week, that the photographers were present and part of the community.

Jean: At the Stonewall Protests, we had such dedicated and passionate community members who are storytellers, photojournalists, archivists, muralists, who would show up. No one’s getting paid for this. No one is earning a salary to fight for Black lives. We are doing this so that we don’t have to in the future. We’re doing this so that we can have liberation now. To feel it, to exist in it. The documentarians who showed up for us have made such an impact. For me, it’s an offering. For our movement to not only have been recorded but to be shared and amplified, for other queer people to bear witness or to be able to hear it, who don’t necessarily have the access to community, to a weekly protest. That truly has been a huge gift and, I hope, something to mark our fight, to show it wasn’t just a onetime thing, that it’s still happening.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy Souls of a Movement (Carlos von der Heyde).

Willis: When we think about the Civil Rights movement, we think about images and film from the [1963] March on Washington, from Selma and the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And the grueling moments, like [the murder of] Emmett Till and other victims of lynching. We have the benefit of looking at past generations and understanding how important visual documentation is for the next ones coming up. But, something we grapple with as Black trans and queer people is that we often weren’t in the frame, both physically and metaphorically, and so we continuously are excavating ourselves and our direct ancestors in these stories and histories. What are your thoughts on the importance of documenting what’s happening in real time?

Jean: I think it is so important and necessary to document, period. If we don’t know where we’ve come from, we won’t have the full knowledge to take us to where we need to go. But I completely agree that it often feels like excavation work. We are literally trying to find the fossils of our Black trans history. Trying to find any recollection, any relic that connects us to our past. I often think about the photographs and video footage of Black people being hosed or beaten by batons, things that are now archetypes of Black American experience and culture, unfortunately. So what does it mean to see Black trans people celebrating, having joy, being in community with one another, being able to rejoice, to not only mourn another sibling’s life but to celebrate it in the way that Black people do? That is part of our culture, to have a repass that does not just exist in a home, that truly carries out onto the street, that alerts and informs the entire neighborhood that Black trans lives are valuable, that so many of our siblings deserved better. They deserve to be alive, quite frankly. So I’m grateful that this visual documentation allows for this message to continue, to keep these names, faces, and lives in print, in vogue, in conversation as part of our culture.

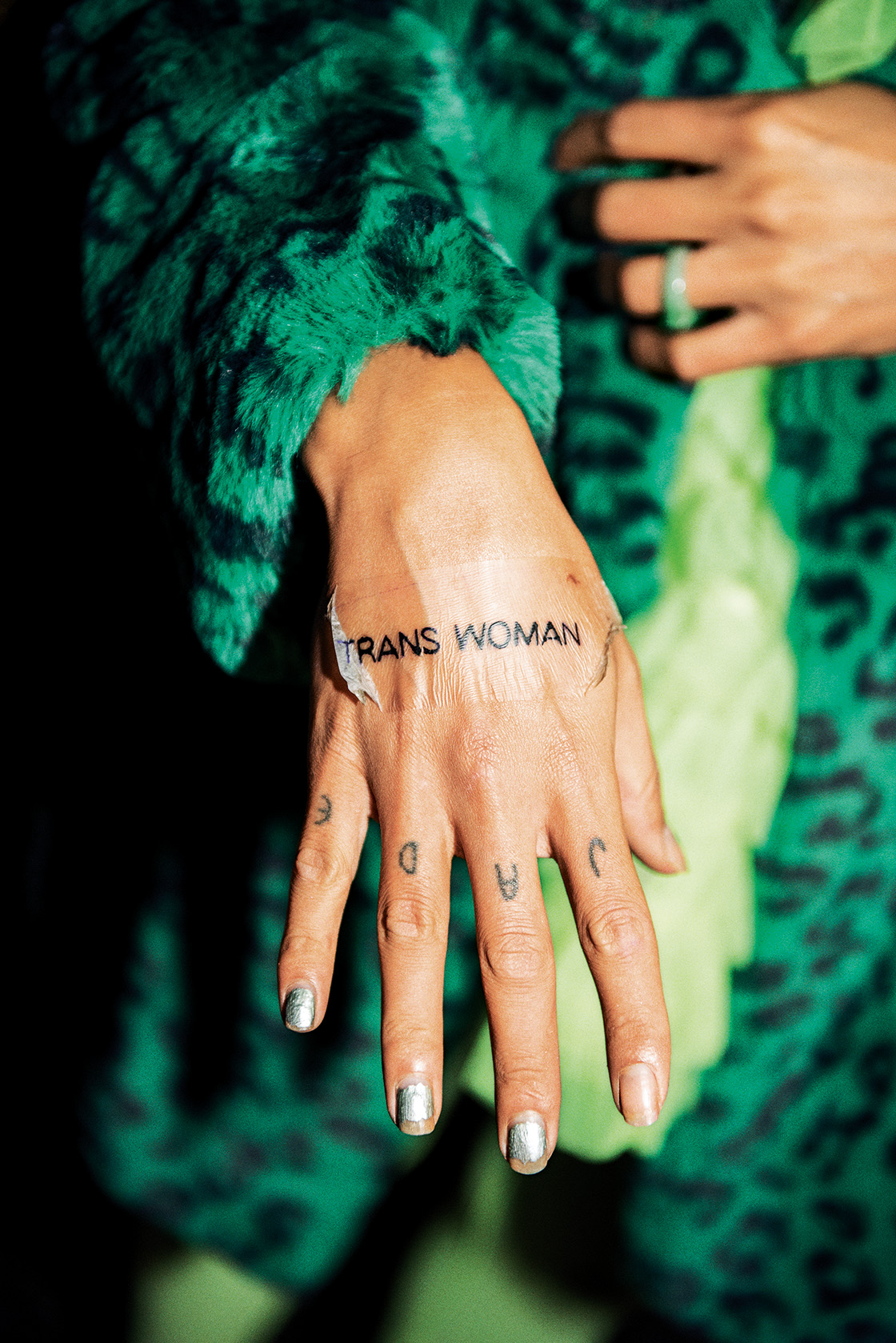

Willis: We often talk about this moment as the visibility era for trans people. But I’m eager to see us find new ways to express ourselves that don’t have to check off any more boxes. Visibility is a double-edged sword. It’s not all shiny and glamorous, and it shouldn’t have to be. We shouldn’t have to look or sound a certain way, be educated in a certain way, have a platform or microphone, or have a specific type of body to be visible and respected.

Jean: Just as our Blackness is varied and beautiful, so is our transness, our queerness. In the present day, we are still fighting, even for our own community to fully see us. And not just to tolerate us, but accept us and truly respect us as Black trans individuals. How do you see visibility and representation in our fight?

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Willis: I think visibility and representation obviously are important, but visibility was never going to save us in a world that still isn’t ready for us. Ultimately, I think the most important thing is vitality. The most important goal is, how can we keep our people healthy, safe, and alive, and how can we improve their lives? And that means all our people, not just the ones who have been accepted as exceptional. But we’ve always done that, so it’s in us. It’s innate. We’ve just got to listen to those voices and to each other.

Jean: That is such a powerful credo, but it is a very tough thing to do. But like you said, we’ve been doing it, and we’ve been doing it without a Greenbook of our own. We’ve been literally building our foundation and building our own grassroots pathway towards liberation. And that is exciting.

Willis: Something I think about is: How do I leave the door open wider for the next person? And how do I make it so that they don’t have to check off as many boxes as I had to? How do I acknowledge the intersection of my own privileges, my personal will and hard work, and the foundation of my ancestors that all played a role in me getting to where I am? And that was one of the beautiful things about the Brooklyn Liberation march. That day felt like ego death, you know? This amazing high in which I didn’t feel a separation of myself from the collective. I want to continue to be a part of making those moments happen.

Courtesy the artist

Jean: I also think about Marsha P. Johnson often: the impact she had, the lives that she will continue to change. It’s so important to tell these stories. It is so important for us to excavate and unearth our past, as we have in this conversation. I’ve been really moved by that tonight, so thank you for that.

Willis: Thank you! I’m sure Marsha would be very proud.

Jean: I’m grateful to be surrounded by so many other fearless, powerful community leaders and icons. We don’t always get to see the full breadth of life for us, the painful truth is that the life expectancy for Black trans people is thirty- five years. And so it is necessary to uplift the joy that I associate with us as a Black queer community. That is how I would first define us, that we are joy. Not pain, not death. We are truly joy.

This interview originally appeared in Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation (Aperture, 2022).