Essays

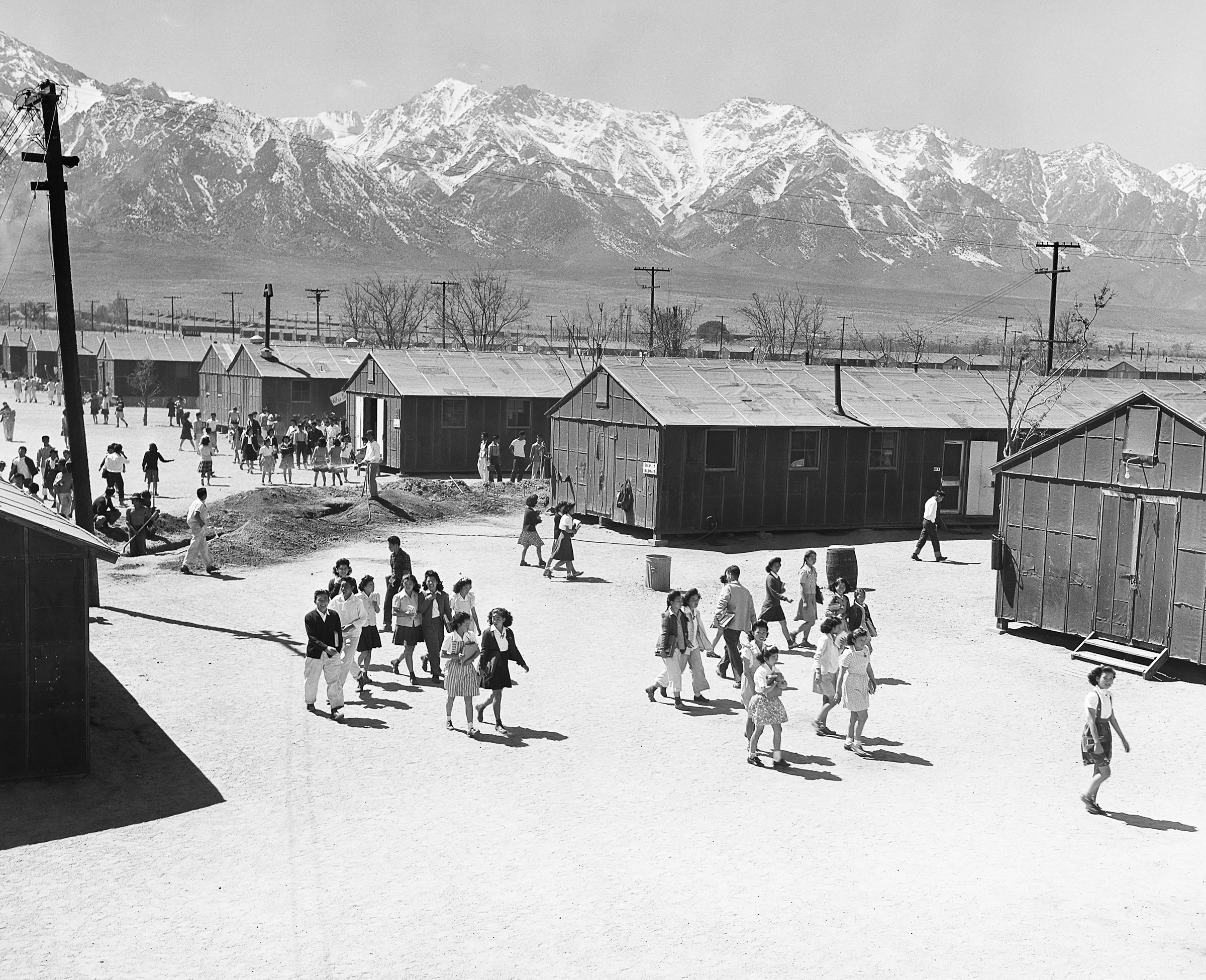

Toyo Miyatake’s Indelible Record of Life inside the Manzanar Internment Camp

During World War II, Miyatake made surreptitious photographs of Japanese Americans incarcerated by the US government. He saw little need to glorify, humanize, or even individualize the prisoners—because he was one of them.

The week after Trump won the presidential election, I attended an Asian American community meeting in Manhattan where one of the attendees told me the following story. The day after the election, he ran into a senior partner at his work, jubilant about the results. Now, the older man said, we can finally round up the gays, the Muslims, and the immigrants. Shocked by this brazen declaration, my new acquaintance pointed out that he was gay himself, and the children of immigrants. When he returned to his office, he saw an email. It was not an apology. The partner wrote that Korematsu v. United States—the 1944 Supreme Court decision justifying the Japanese American prison camps—was still good law.

This senior partner wasn’t alone. I remember waiting for a flight at an airport and watching Fox News pundits suggest that the prison camps provided a precedent for us to register and imprison Muslims. Then ICE started taking children who had traveled across the border and throwing them in Fort Sill in Oklahoma, which once imprisoned some seven hundred Japanese Americans. I thought the camps were ancient history, an Asian American friend bemoaned to me at a coffee shop. But they weren’t.

In 1942, Toyo Miyatake left his studio in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo and brought his wife and four children to the Manzanar concentration camp in the central Californian desert. Cameras were prohibited, so Miyatake snuck in a lens and fashioned a wooden box into a body for his surreptitious camera. “As a photographer, I have a responsibility,” he told his teenage son Archie. “I have to take all the pictures in Manzanar to keep a record of what’s going on here.”

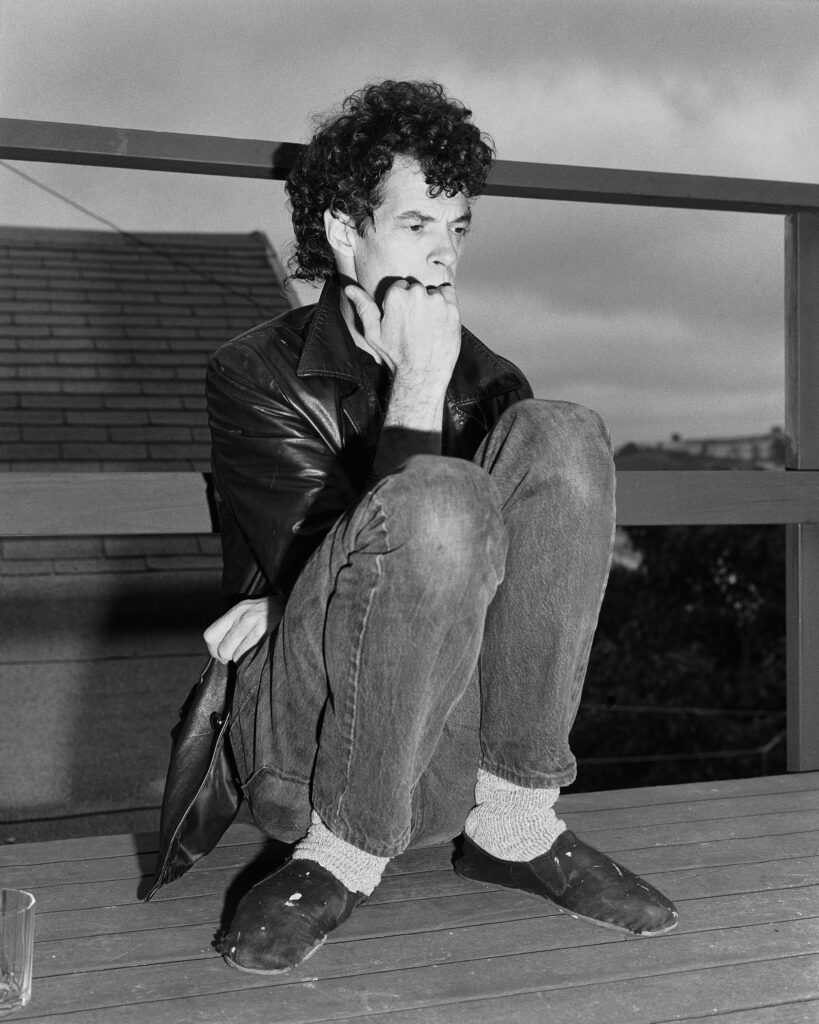

An unusual candidate for incarcerated auto-ethnographer, Miyatake had been a well-known Pictorialist before the war: a friend of Edward Weston’s, a collaborator of the cinematographer James Wong Howe, and winner of an award from the International Photography Exhibition in London. His métier consisted of poetic abstractions. His landscapes captured no humans, just the delicate shadows of bushes, falling like brushstrokes over snow-covered hills. The figures in his Little Tokyo cityscapes exist only as silhouettes. His dancers, gestures of shadow and motion. But there was another Miyatake: the much less expressionistic professional photographer who ran a commercial studio. He courted his wife by taking her picture, yet his most libidinous portrait shows Michio Ito, the charismatic performer who danced alongside Martha Graham and inspired W. B. Yeats’s Noh theater experiments. In Miyatake’s portrait from 1929, Ito seems capable of conveying modernist ferment through just a hairstyle and a glance. His hair hides his face in a center part, but even this obscured gaze communicates an erotic recalcitrance. He looks like he’s arrived from the future, the way silent-film actors sometimes do—or at least from the grungy glam 1990s of the actor Leslie Cheung.

What did Miyatake, driven by a mission to document an abhorrent experience, decide to preserve?

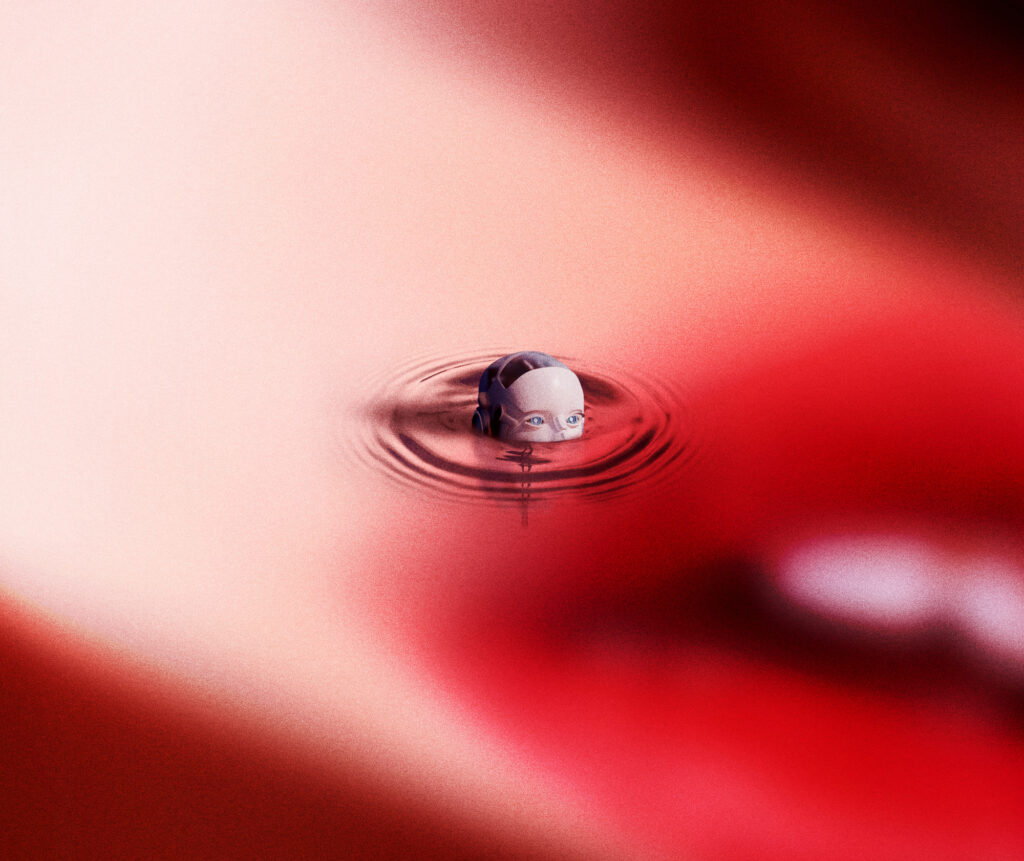

In 1942, Ito was deported to Japan as an enemy alien, and Miyatake banished to Manzanar, a dreamy aesthete and studio portraitist in a prison wasteland. When viewing the colonial archive, we often search for how oppressed people understood their own predicament. For life at Manzanar, we can simply look at Miyatake’s photographs. What did this man, driven by an ethical mission to document an abhorrent experience, decide to preserve? A baseball batter readying for the pitch. Children cradling their dolls, borrowed from a toy loan center. Smiling majorettes twirling their batons in the air. When I’ve taught the literature of the Japanese American imprisonment, it is precisely these details that trip students up—the sense that daily life continues, even in a concentration camp. In Farewell to Manzanar (1973), Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston describes her brother’s playing in a prison swing band. In Citizen 13660 (1946), Miné Okubo writes that the prisoners at the Topaz camp in Utah “went wild with excitement” over a snowball fight. Why, my students essentially asked, wasn’t everyone constantly miserable?

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Obviously, we shouldn’t undersell the camps’ fundamental crappiness. These permitted types of recreation were ways of assimilating prisoners into American nationhood (baseball!). When Miyatake was at Manzanar, sewage tainted the drinking water with E. coli. Residents died in the sweltering 110-degree heat. Military police fired on a rioting crowd, killing two. “Manzanar was a devil’s playground,” said Fukiko Elisabeth Komatsu, imprisoned with her mother and siblings, “and the dust storms came through at 60-miles an hour to make our lives even more harsh and miserable.” Nor did Miyatake live at the Tule Lake concentration camp, the prison for the radicals, which Konrad Aderer’s documentary Enemy Alien (2011) calls the Guantánamo Bay of the Japanese American incarceration experience. There, prisoners were shackled in the camp stockade, shot at by battalions of tanks, or simply executed in broad daylight. We might describe these prisons using the work of the theorist Giorgio Agamben, who writes that during crises such as the Third Reich and, arguably, post-9/11 America, groups can become stripped of their legal status and reduced to what he calls “bare life.” My students were essentially asking, “Why weren’t the prisoners diminished into pure abjection?” The answer is that Agamben was wrong. The men locked up at Attica prison wrote poetry. People in refugee camps, which activists wryly call the most permanent form of architecture, still find ways to care for one another, make art, and live life. Miyatake photographed women getting their hair done.

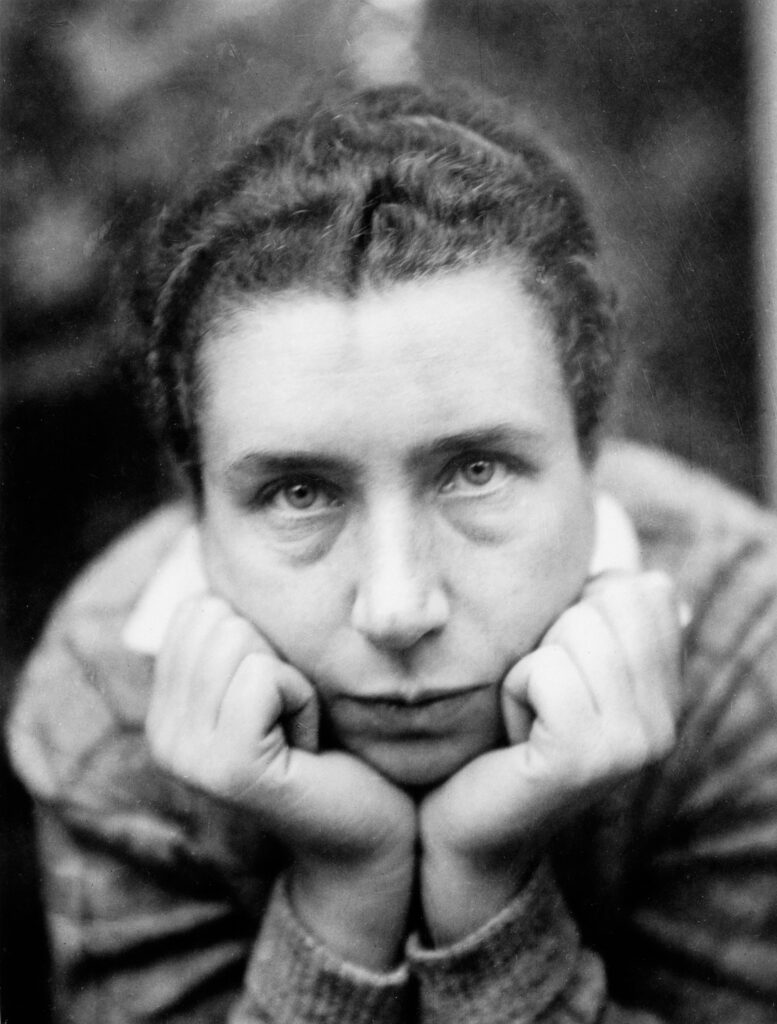

“Although Miyatake lived in the hothouse environment of simmering anger, fear and suspicion that some Manzanar chroniclers have described,” the author Nancy Matsumoto writes, viewers may be “disappointed,” because “his photographs bear no signs of violence or anger.” The enigma of his images is their mundanity, which we can better understand if we compare them to those of Manzanar taken by two of America’s most famous photographers, Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. A landscape photographer uninterested in portraiture or politics, Adams wanted to show that the prisoners weren’t terrorists but smiling schoolgirls, Norman Rockwell–esque nuclear families, and proud men in uniform. What did Adams omit? Any cultural difference, as well as the barbed-wire fences and guard towers.

Dorothea Lange called Adams’s efforts “shameful.” Her photographs, which were censored and impounded by the military until 2006, depict Manzanar as a stark, perpetually dusty prison. As in her migrant portraits, she displays a novelistic ability to capture her subject’s gaze, the solemn look or glance cast slightly askew, insinuating some private turmoil. While Lange’s images are generally seen as better than Adams’s, both had one thing in common. They took photographs of their own projections. Adams saw the prisoners as model Americans, Lange as people experiencing injustice. Miyatake did not understand the Japanese Americans as political idealizations—and that is exactly what perplexes us about his work. He saw little need to glorify, humanize, or even individualize the prisoners. For he was one of them.

One Miyatake photograph shows a crowd facing the monument at the center of the Manzanar cemetery. The obelisk fills the left third of the image, a white geometry, its paleness continued by the flecked outline of the Sierra Nevadas. Aside from a girl looking toward the camera, we cannot see any of the mourners’ faces. Their bodies form a black mass barely recognizable as people. They turn away from us. They will not tell us what they know.

Avoiding the poles of didacticism and aesthetics, Miyatake documented outside such binaries. “Not yes or no, it could be maybe,” the artist Hirokazu Kosaka says in the 2002 documentary Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray. “It’s not white or black but infinitesimals of gray. That’s what Miyatake was trying to create.” Some of his images lack any people, depicting Manzanar as a barren environment. Barracks tile and recede to the background, but instead of a horizon opening to a broader world, the foreground is encased by Mount Williamson. Not unlike in Hokusai’s prints of Mount Fuji, the peak is a spectral crystal, a gargantuan mass always visible but never foregrounded, the inescapable reality of imprisonment banished to the unconscious.

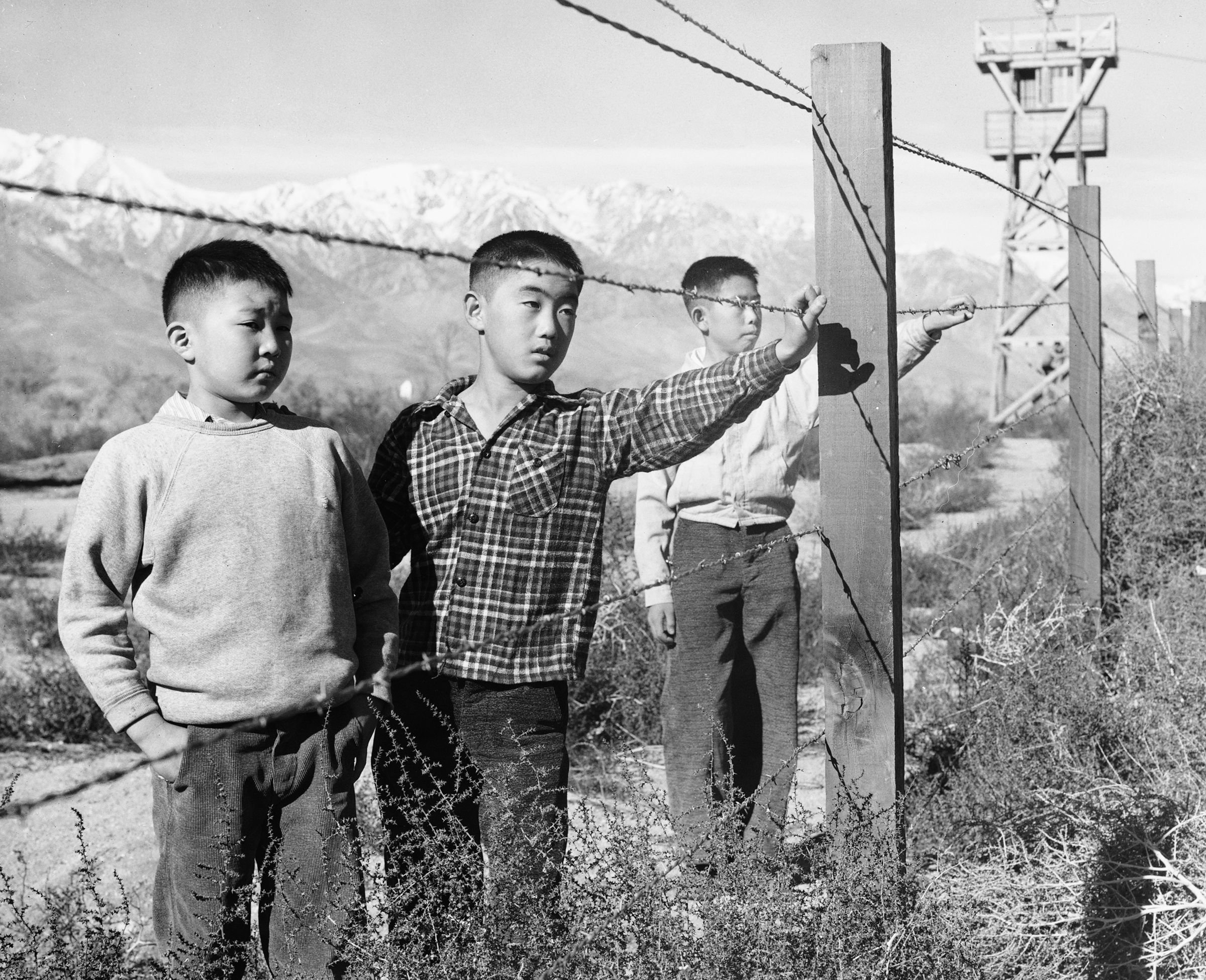

Toyo Miyatake, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire, 1944

All photographs courtesy Toyo Miyatake Studio

It is not necessarily that Miyatake preserved some authentic truth. Another photographer who once worked at his studio, Jack Iwata, composed similarly quotidian photographs of daily life in these prison camps, but his images occasionally suggest more emotional range, both stark drama (American soldiers holding bayonets as cars enter Manzanar, black smoke rising up in plumes from a fire at the Tule Lake camp) and joy (a woman wearing a crown declaring her the Queen of Manzanar). Seen beside them, what emerges in Miyatake’s photographs is a meticulous reticence, a refusal of the evocative flourishes he once adopted as a Pictorialist. He became the diarist of a society, one who, whether because of personal temperament or camp surveillance, did not photograph the violence of the prison. Instead, he documented weddings, graduations, newborns entering the world in a prison. Both he and the photographer Corky Lee were forced by Pacific wars and spatial segregation into becoming community archivists, but they traveled in opposite directions. Lee had a flair for adventurism and famously captured Chinatown protestors brawling with cops. Miyatake spent the Manzanar riot in his barrack. Lee was a radical who gradually adopted expressive and inventive forms of mise-en-scène, but Miyatake left behind his lavish romanticism and the formal poses of his portraits. Unlike Lange’s brooding depiction of ruminating prisoners, what is most mysterious about Miyatake’s photographs is that we do not know how to make them available for our own emotional use.

Unlike Lee, Miyatake rarely took photographs that overly implied a political message, but there are exceptions. In a photograph for the 1944–45 Manzanar yearbook, a hand holds up pliers, positioned as if to sever the barbed wire slicing the background. His most famous photograph, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire (1944), shows three boys considering the steel fencing that diagonally intersects the frame. A guard tower stands behind them. Unlike Miyatake’s more quotidian portraits, this image vibrates with implied psychology and the sense that these imprisoned children also serve as symbols of some sort. There is a less famous version of this photograph in which only one of the boys touches the wire. He bends back slightly, his shoulder tucked back awkwardly, and connects a single finger to the wire, as if feeling for the prick of the barbs. In the more well-known image, two of the boys raise their hands and almost lean on the wire, like dancers lined up on a ballet barre. They are testing the boundary.

While it is tempting to reduce Miyatake’s photographs to documentation, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire was more constructed than it appears, the scholar Jasmine Alinder writes: the boys actually stood outside the camp and looked in. Many prisoners found the incarceration experience too terrible to talk about, so perhaps we can read the photographs as not only describing the implied barbarism of locking up children but representing their future selves wondering how to probe the repressed past. Akemi Ookas, the daughter of one of the boys, reconvened the three subjects, now in their eighties, for the 2017 documentary Three Boys Manzanar, a project not unlike Lee’s 2014 restaging of Andrew J. Russell’s 1869 golden spike photograph—taken in Utah to commemorate the completion of the transcontinental railway—to include descendants of Chinese rail workers.

If the boys stood outside looking in, this meant Miyatake positioned himself inside the prison. When the war ended and the camps opened, some, rather counterintuitively, did not want to leave. They may have had nowhere to go. The push toward incarceration had been driven by corporate agribusinesses, which seized more than a quarter of a million acres of Japanese American farms. Leaving meant relinquishing the community of the prison camps for the very racist world that had imprisoned them. Consider a man named Joe Takeda, who returned from the Gila River prison to his San Jose pear orchard, where assailants poured gasoline on his home and shot at his car. Miyatake did not leave immediately. He stayed and documented those who lingered. Ralph Merritt, Manzanar’s director, warned the now-free residents against “crowding into the seven southern counties of California” and creating “another Japanese problem.” Miyatake did the opposite. He spent the remainder of his life photographing Little Tokyo. With both the Pictorialist movement and his fine arts career having molted away, he trained his camera on the weddings, families, births, and deaths of those who lived there. “So, the ancestors are looking down. / The poet, and/or his poem, is looking up,” writes the poet Brandon Shimoda, whose family members were imprisoned in Utah, Montana, and Wyoming. “We are in between.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”