Interviews

Wendy Red Star on the Power of Indigenous Art

In an interview from her Aperture book, the celebrated artist discusses family bonds, Native history, and how studying sculpture inspired her genre-defying photography.

In her dynamic photographs, the influential artist Wendy Red Star recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective. Red Star, who was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in October 2024, centers Native American life and material culture through her imaginative self-portraiture, vivid collages, archival interventions, and site-specific installations. Whether referencing nineteenth-century Crow leaders or 1980s pulp fiction, museum collections or family pictures, she constantly questions the role of the photographer in shaping Indigenous representation. In the following interview with Josh T. Franco from her book Delegation (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2022), Red Star speaks about her family history, what it was like to collaborate with her daughter, and how her multifaceted practice gleans from elements of Native American culture to evoke a vision of today’s world.

Josh T. Franco: When and where were you born?

Wendy Red Star: I was born in 1981 in Billings, Montana.

Franco: What were your parents doing at the time?

Red Star: My mom is of Irish descent, and she grew up in Colorado. She went into nursing through the army and that took her to Korea, and she was stationed there for a while. She adopted my sister there, and then came back to the States and continued her nursing career, and decided that she wanted to work on a Native American reservation. She looked into the Crow Reservation and Pine Ridge, a Lakota reservation in South Dakota, and I think one other one, and she chose to go to the Indian Health Service in Crow Agency, which is where my reservation is.

Franco: She adopted your sister before she met your father?

Red Star: Yes. She was young. I would describe my mom as being really adventurous. I could not imagine myself at that age being in a foreign country and deciding to adopt a child. Also, her decision to work on a Native American reservation and at the Indian Health Service was very progressive.

My father is from the Crow Indian Reservation, and at that time he was working for the tribe as a game warden. And they met just because everybody ends up going to the Indian Health Service at some point. I think one of his cousins was working with my mom and then introduced them.

Franco: So was it love at first sight?

Red Star: I have no idea [laughs]. My parents never got married. And I have four half-siblings from my father—he was forty when I was born, and my mom, I think, was twenty-nine.

I have a very special bond with my father. He was able to get my grandfather’s land out of a non-Indian lease. It was leased by this white family for over fifty years. I would go with him on the weekends, all summer, while he ranched that land.

Franco: What does it mean to be a Red Star?

Red Star: There’s a lot of pride in it. My sister and a lot of my cousins have Red Star tattoos. The name itself has a very interesting history, and it ties into all the Crows on the reservation. Red Star is my great-grandfather. When they were allotting the land, he was of that generation where he was a head of household. All his family members in his household were then given his name as a last name. That’s how I got my last name. There’s a lot of beautiful Apsáalooke names—and it can all be traced to one individual around the allotment of the Crow reservation.

Franco: Do you have memories of making art in childhood?

Red Star: I daydreamed and I had a very vivid imagination. I was able to entertain and occupy myself, and spent a lot of time alone as a kid. I was having to fill that space with creation, or creative ideas, or fantasies. And so, now, it’s really important for me to walk out in the woods. That’s where all my ideas either come to me or, if I’m stuck, I find solutions, and it’s just so important to have that time and headspace. And when I think about it, I’ve just been doing that since I was a little kid.

I went to school in Hardin, Montana, which is just off the reservation. The reason why the white folks wanted to remove Hardin from the reservation and incorporate the town is because they wanted to sell alcohol to Crows, and that was a big profit for them. I found that to be fascinating, because my dad remembers going to Hardin. Hardin is super racist. And there would be “No Indians allowed” or “No Indians allowed in the bar” or whatever signage, and actual segregated places for them to use the bathroom and stuff. It’s just crazy to talk to somebody, you know, actually talk to my dad, who has had that experience.

Franco: Did your high school give you space for making art?

My high school art teacher focused on realistic drawing, and I just didn’t excel in that at all. This is when in the art dynamic—which you continue to see—the people who are able to realistic-draw in the art class are the art stars. I was like, I’m not a good artist. I think I took one semester, and then I was out. I never took an art class after that in high school.

Franco: What did you do the rest of high school?

Red Star: I found this other teacher who was totally wacky. She ran the computer class, and the thing she focused on was video editing. I was having a blast. And she called this whole process “graphic design.” I was like, That’s what I’m doing. I’m going to be a graphic designer. I graduated in 2000, and I ended up going to Montana State University in Bozeman, which is about a three-hour drive from the reservation, and enrolled in graphic design as my major. And that was a very rude awakening [laughs].

Franco: Was that more like poster design?

Red Star: Exactly. And working with different fonts and kerning. I was like, What the hell is this? I soon realized that my high school teacher was totally misusing the term graphic design.

Franco: While you were still in school in Hardin, you spent your summers in Pryor with your dad ranching?

Red Star: Yes. My dad would get me on the weekends. What bonded me and my dad was horses. I was going out to the land, and I would just ride horses all day long while my dad would be on a tractor for like eight to ten hours. I was alone, but I didn’t care, because I had my imagination, and I had my horses and bologna sandwiches. Our horses roamed free like wild horses. I would do everything that they did, and I knew when they took their nap, and I knew when they went and got their water, and then they would follow me and I would take them and say, “We’re going to eat over here.” I learned the language of the horse.

Franco: When you went to college, what did you major in?

Red Star: Well, I started out in graphic design, and then I went into a minor in Native American studies. That was super important, sort of a revelation, to take Native studies classes. At first, I thought it was a joke. It’s kind of like when somebody takes a language course and they already know how to speak the language.

Franco: You thought you were going to get an A.

Red Star: Yeah. What I soon found out was I knew nothing. I didn’t even question why there was a reservation. It was just where I grew up. You know? Then I started learning, and it just blew my mind, because that was not taught at all in my history classes. We never touched on anything near what I was learning in Native studies classes.

Franco: Do you remember any things you made then?

Red Star: An important series I made then is called Interference (2004). It’s a piece that is foundational for the way that I work today, in that I learned about an important chief of ours called Sits In The Middle Of The Land. He’s the one who told the US government where our territory was, basically, and he’s the one that said we had over thirty million acres. But he used this beautiful metaphor of the foundational way that we set up our tipis, which is with the four poles. And he said, “My home is where my tipi sits” and then he placed each of those four poles on the major seasonal migration stops that we would camp at. To me, that was kind of the first time of really thinking about a Crow perspective, and how beautiful that was, and how much that takes me out of Western thinking. Like, the home is where the tipi sits, and the tipi actually is a woman. The interior is the womb, and you’re being hugged by your mother, and to think the Earth is your mother.

So it’s really interesting to have him illustrate that in this way, and then to have the US government be like, Okay, let’s draw a line around thirty million acres. You know, reduce it down. That inspired me, because when I looked within that land base, Bozeman was actually Crow territory. I was shocked. My reservation was about 2.25 million acres, three hours away. I harvested lodge poles, and my dad and mom came and helped me set up tipis around campus. This research project was inspired by a photo—I saw a photo of him, and I was like, Who’s this guy? Then from that, I found out about his speeches and from there, produced a work.

Franco: How was it received on campus?

Red Star: The tipis didn’t have the canvas on them. A lot of them were just the four-pole structure. I would scout pieces of prime real estate that students used to cut across, and see if they would go through it or go around it. But what ended up happening was the tipis were being knocked down. I thought, Well, maybe it was the wind. Then I realized that somebody was knocking them down. Which then prompted me to put them on the fifty-yard line in the football field, and that was the end of the project. They’re all documented through photo. But to me, it was very much a sculpture in addition to a performance and a photo. But I was really minimizing photo. That’s just the documentation of it.

There was a visiting professor teaching sculpture at the time, and he said, “Wow, you really like to make political work.” That was our home. There was nothing political about it. It’s the truth. People tend to think a lot of my work is political, and I’m not offended by that. But really, it’s just a fact. And if that fact is political to you, then that’s interesting.

Franco: You went to UCLA for grad school and studied with Nancy Rubins. What did you learn from Nancy?

Red Star: Nancy had this solid belief in me. I was really a fish out of water because, in my undergrad, we didn’t learn anything about contemporary art. Contemporary art was Salvador Dalí [laughs]. Some of my grad peers had full-on art-monograph libraries. And I was like, I don’t know any of these artists. I was severely lacking. And going to UCLA was a very steep learning curve. One of the professors I took a seminar with was Ron Athey, and I did not know who he was or about his work. The first day of class, he said, “I’m going to show you my work.” I went from Salvador Dalí to pearls coming out of an anus with the sun tattooed around it.

After Nancy left, she invited me to be in a group show at the Cartier Foundation in Paris, France, which invited their past exhibiting artists to select a young artist who they had mentored to show in a group exhibition. The summer after my first year of grad school, I ended up flying to Paris with the photos of the tipi series. All these young students were so excited to be showing in this amazing institution. The opening was a big party, and I remember Takashi Murakami was there, and he had this entourage of young people. Nan Goldin was there. And we got to go up on the roof of the Cartier, and the Eiffel Tower was sparkling.

Franco: Magic.

Red Star: I remember sitting there with my friends, who came to support me from UCLA. Like, this is part of being an artist. You can do shit like this. I thought, I will never attain this level ever again. This is it for me. This is so incredible.

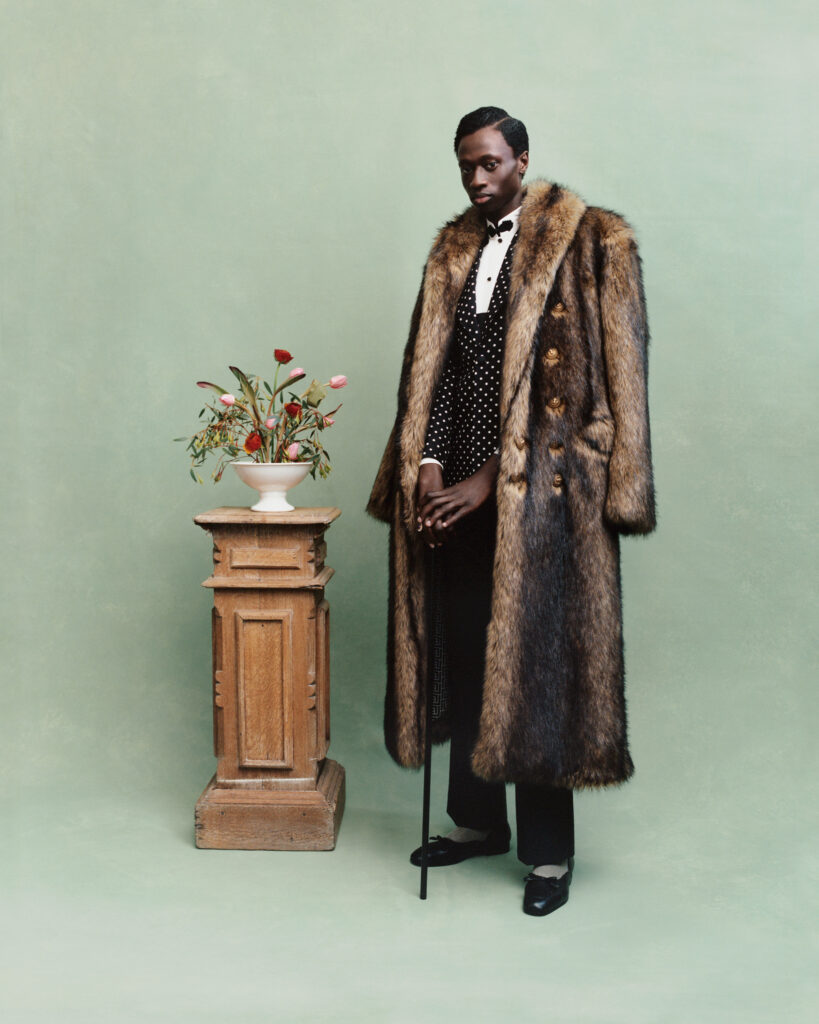

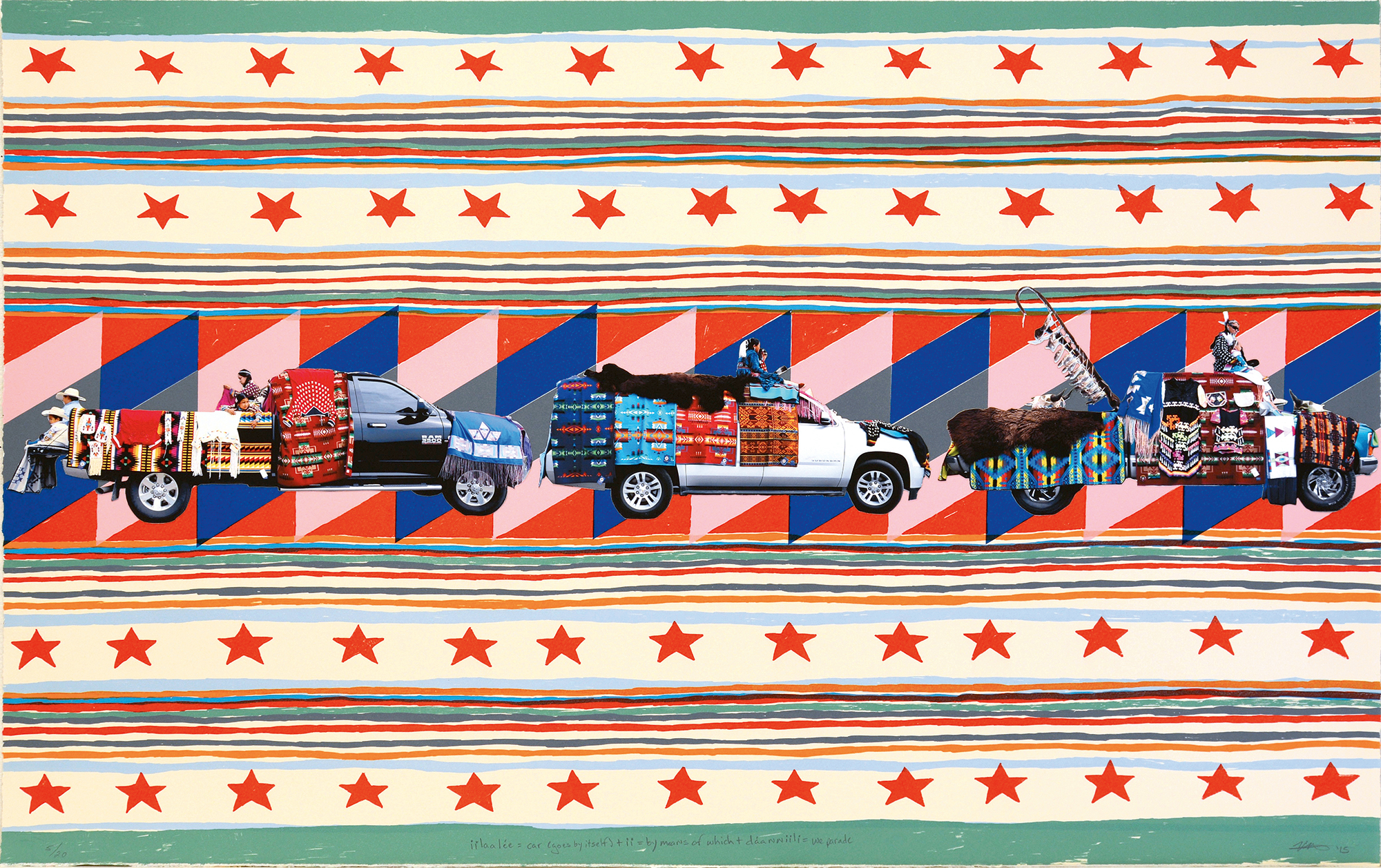

Wendy Red Star, Hawate (One), from the series A Float for the Future, 2021

Franco: Did your time at UCLA give you any names or bodies of work that became touch-points?

Red Star: The thing that really turned me on were people doing identity-based artwork, like Fred Wilson and Adrian Piper and Kara Walker. Because there were maybe two other artists in the program focused on identity-based work. I was the only Native student. There were other artists of color there, which was awesome. But we were the only ones that were doing work based on identity. And we were, I felt, very ridiculed for it and always told that we need to just get over it, like we were being didactic. And especially the work that I made and the content I made, I think, intimidated people. Now, what I realize is that the work just made people uncomfortable, because it pointed to the missing spaces in their knowledge. I talk to other Native students who are in art programs now, and they’re still feeling the same feelings that I felt. It would be really hard to hear, you know, a studio visit in the next studio going so well with somebody who is doing abstract painting—a white student—and then to have that same professor come in and say, “Uh . . . can you, like, fill me in, give me a little history lesson?”

Franco: Was feminism part of the conversation in grad school?

Red Star: Not at all. It was even about being genderless, more like not being a woman, was kind of the goal. I had a professor, a visiting professor, who was Korean. And she said that was her goal—that when people looked at her work, they would not know her gender or her identity. So that’s kind of where I was at. Me doing work about my culture and being a Crow woman was so not the deal.

Franco: Are things different now?

Red Star: Early this year, I got to be a visiting artist and do a lecture and studio visits virtually with UCLA grad students. They’re having such a different experience than I did.

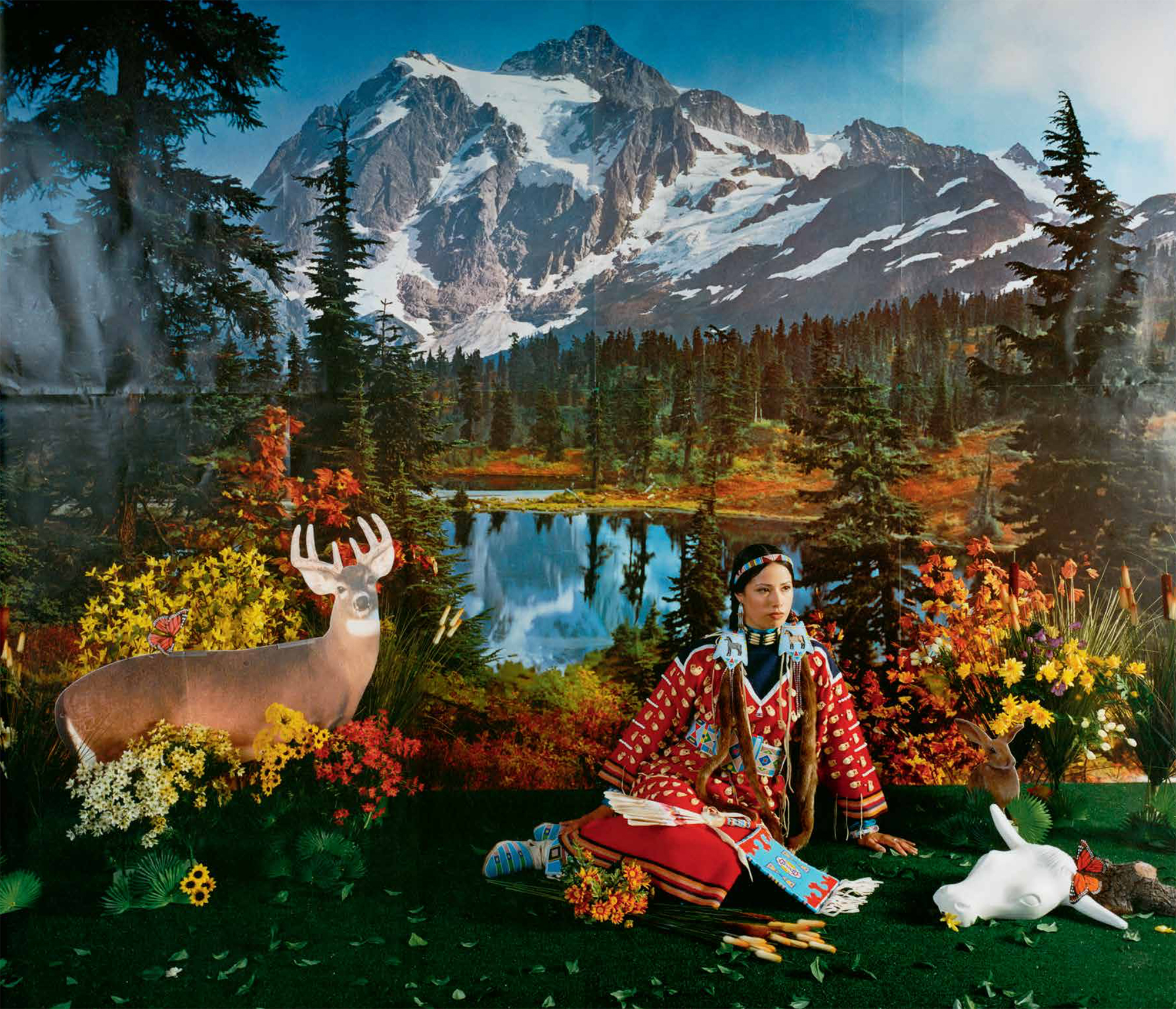

I made one of the most important works of my career, Four Seasons (2006) in graduate school. And that was everything. I had a studio visit with Cathy Opie and Robert Gober, which was a dream. They talked about Four Seasons, and that’s the first time I heard the word tableau.

Franco: Is it fair to say that Four Seasons is a little tongue-in-cheek?

Red Star: Oh, yeah. I was watching a lot of John Waters’s movies.

Wendy Red Star: Delegation

65.00

$65.00Add to cart

Franco: That makes total sense.

Red Star: I was interested in sets, and I found out that I could rent objects—that’s the way that it worked for movie sets. And then there was the influence of other grad students, especially one who had these seventies photomural backdrops, and he showed me where you get them. I was actually told by the sculpture tech, “If you can’t make it, someone in LA can.”

Franco: Did you go to Skowhegan immediately after grad school?

Red Star: I went to Skowhegan in the summer of 2006. And it was like an oasis in the sense that it was the first time that I’d been around so many artists of color who were working on identity-based artwork. And that gave me real faith that there were other artists like me out there. There was a community from all different backgrounds and cultures. And I met my ex-husband at Skowhegan. An extremely important and amazing thing is that my daughter came from that union.

I found out I was pregnant when I was at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, so I didn’t get to do the full round. I came to Portland because he is a professor at Portland State University. And that was the very first time that I’d ever been to Portland, spent time in Oregon. I had no clue what a weird little town this is. At first, I just really did not know what to make of Portland, but I’ve grown to love it for the access to quick hiking and amazing food, of being able to do a waterfall hike and eat fancy donuts. The textile community here is super strong. I love to sew. I started sewing here.

Franco: What were the significant bodies of work you made during this period?

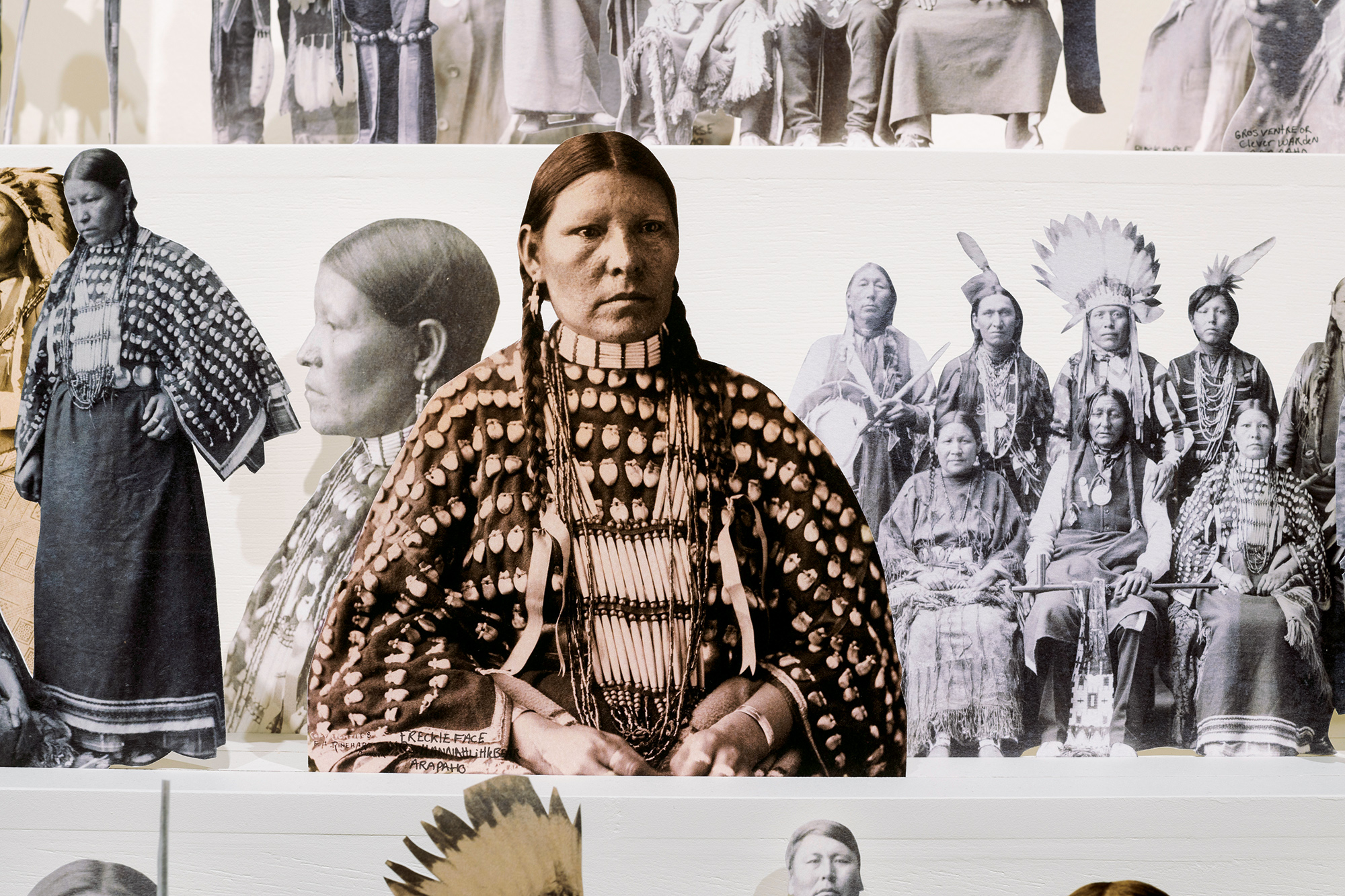

Red Star: In 2014, I made 1880 Crow Peace Delegation (2014), and I also made a series called White Squaw (2014). 1880 Crow Peace Delegation is a set of ten portraits that were taken of Crow chiefs in 1880 by Charles Milton Bell. They are delegation portraits from a trip that they took to Washington, DC, to meet with the president, and they went there because the US government was going to put a train through a large tract of our hunting territory. That was the first time that I investigated this very popular image of this one chief, Medicine Crow. Because his image had been used commercially a lot, like on Honest Tea. It was the first time that I actually was like, What is going on with this photo? And that body of work introduced me to archives and to museum collections, and actually looking at the Portland Art Museum’s collection of Crow objects, which then got me into the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship program.

Franco: What did you do to the photograph?

Red Star: I was just asking that question: What’s going on in this photo? What happened that day when he sat down to take that photo? I did a quick Google search, and information came pouring out. And then, I would follow the leads. They would take me to different archives, like at Montana State University in Billings—they have all these amazing drawings of circus animals that Medicine Crow drew in relation to that trip.

When I looked into who took the photo, then all the other Crow chiefs that went on that same trip and sat down during that same photo session popped up. I had no idea that they went and were photographed and had the same experience. So I started researching each of those chiefs. And through that, I was like, I want people, when they look at this photo, to actually have a sense of what is trying to be conveyed from my culture in this image. And so, I started outlining their outfits. Partly for myself to really look at all the tiny details. I started to realize that they all wore brass rings on their fingers. I started to notice the details, like the conch shells, and that one of them has an eagle-claw bracelet. And all of that was just stuff that I wasn’t picking up from looking.

I’m also marking on history. And red—I always think about school and failing papers and getting that red mark on your paper. I wanted that red mark on history.

Franco: Literally outlining in red ink on the image.

Red Star: In red ink. And then through that, I would start telling people, “Oh, this is ermine” and “This is an eagle feather that is part of a coup that he had to acquire chief status.” I would look into census records and learn more about them and try to pinpoint their age. Then, if I could find their name written in the Crow language, I would write that on there. And if they had any descendants, I would try to include interesting facts about them and, more importantly, gossip that I heard about them as well from the community. it’s the kind of document that results from an art history student studying in their textbook and writing on it. there’s something spectacular about seeing that very intimate act of study elevated to the scale and status of artwork on the wall.

That’s so great to hear. I really want to humanize, and part of that is getting to see my terrible handwriting [laughs] and my spelling errors, and relating physically to these people in the portraits. It was important to me. But I’m also marking on history. And red—I always think about school and failing papers and getting that red mark on your paper. I wanted that red mark on history.

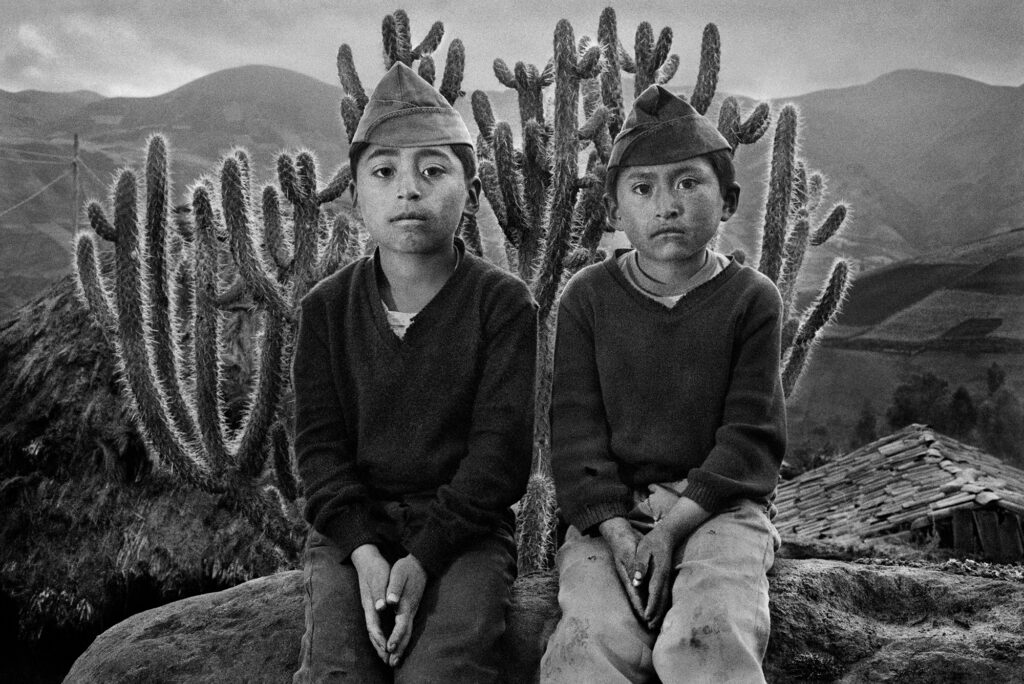

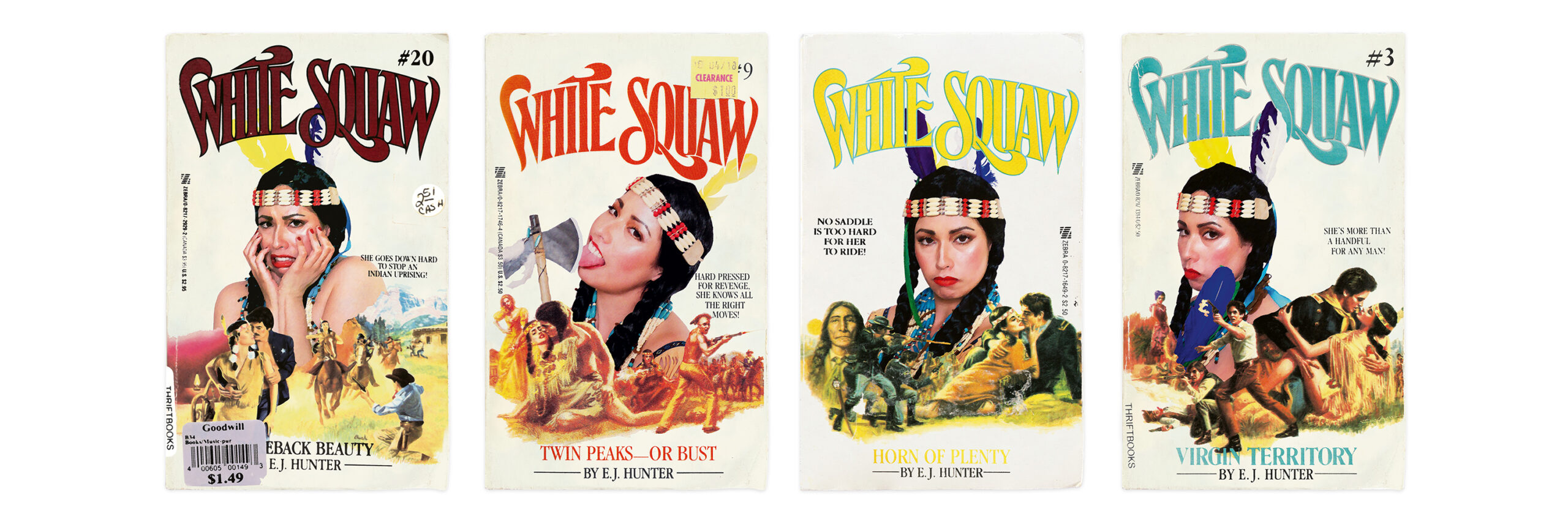

Wendy Red Star, from the series White Squaw, 2014. From left to right: Bareback Beauty #20, Twin Peaks—Or Bust #9, Horn of Plenty #8, Virgin Territory #3

Franco: Did you make White Squaw around the same time?

Red Star: Yes. That was an important body of work. I have so many complicated feelings around it, and I think those feelings still linger today. It came about because I was wanting to understand the origin of the word squaw, because I had heard that it was an Indigenous word that then was turned into a derogatory word. I was hunting that down on Google, and then all of a sudden, “white squaw” popped up, and I was like, What’s a white squaw? It was a movie that was made in 1950. The posters for that movie are incredible. They’re completely stereotypical and racist. The premise is a Native woman, who’s half-white and half-Native, sort of works with the cowboys to get the Native people in line. As I was looking into that movie, I found a book series called White Squaw. They are these trashy 1980s romance, pulp fiction–style books, and there were twenty-four of them. They have outrageous subtitles and taglines (“Buckskin Bombshell” or “Virgin Territory”) and salacious illustrations that combine a portrait of Rebecca—the heroine—with over-the-top narrative scenes. I just could not look away. I thought, I cannot not do something. So I ended up purchasing all the books on eBay. Then I scanned the covers, and I went to Target and got an “Indian Princess” costume. I wore the costume. There’s a choker in there, but I put the choker on as a headband. I bought fake turkey feathers that were different colors. Then I acted out the title. And I replaced her character with my image. I remember I shared one on Facebook, and this Native guy was like, “You know, that’s a choker, and it belongs on your neck.” I was like, “That’s what you’re picking up?”

Franco: Around this time, you also began to collaborate with your daughter, Beatrice.

Red Star: Yes. That happened during my solo show at the Portland Art Museum in 2014. I had all these photocopies of the delegation portraits, and she made a body of work where she colored over the top of them, and I included those in the exhibition. When we went to the opening, on the way there, she asked if she could talk about her work. She was seven at the time.

Franco: Amazing.

Red Star: Beatrice really surprised me, because she can speak publicly very well. I realized with that exhibition that we could work together, and I could learn a lot from her. We collaborated up until 2018. We did some incredible works where we went to museums and gave tours of their collections that started with me saying, “Hey, I’m going to collaborate with my child, you have to be okay with it” to institutions contacting me to come and do a project with them.

Franco: What did it change for your audiences? And did your daughter end up building her own audience?

Red Star: I think what it was really important for, more so, was the institution, and the institutions recognizing that a collaboration of this nature can work. And not only can it work, it can be powerful and successful. Beatrice can take the public aspect very well. She has no problem gathering people to come and do activities. At the Denver Art Museum, she gave three tours to children of the Native galleries and the Western art galleries, and they were blown away. Because they had never seen little children pay so much attention to a tour. I think they were like, This is how we connect with the future generations, it would have to be through that generation’s perspective. That was something that was really important for an institution to be open to, and to see the power and the potential.

Franco: You sewed her outfit for that, right?

Red Star: I did. She really got into the whole tour-guide aspect and persona, and she would draw up outfits that I would sew. We even did a lecture outfit, so when we did dual lectures together, she would have one.

There’s one other thing that Beatrice and I made together, which is Apsáalooke Feminist (2016), self-portraits of us in our living room on our IKEA couch, in our elk-tooth dresses, that we did with a self-timer, jumping back and forth. That’s an important work for us. Beatrice will be getting the artist proofs for all of my work, whether she likes it or not.

Franco: And then she retired?

Red Star: Yeah, she retired at age eleven. Like I said, we were on a roll, and then she said she wanted to have the tours at the Pulitzer Art Foundation to be her last thing. And I was okay with it, because it was intense for me as well. Not only did we have to do a project and have it be successful, but I also had to shelter her from the business side of things so that she could be a child, which she is, and just enjoy the moment and the time together.

Franco: The Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship invites artists to spend one or two months researching in collections across the Smithsonian. it’s kind of a byzantine process to apply and select an adviser. Do you recall?

Red Star: I do. I remember Shan Goshorn. She was dying of cancer. And I saw her in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She had this sense of urgency. She was like, “I want you to apply.” It’s so important what she did—when artists show up for other artists. Anyway, I got in. And wow. It’s so monumental, every aspect of the Smithsonian. It’s not at all what I was expecting. I thought I was going to be at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), on the Mall, not realizing that all the material objects and photographs that I wanted to see are in a suburb in what looks like a Costco warehouse.

Franco: Who was your adviser?

Red Star: Emily Moazami. I worked with the photo archive. I worked with the American Museum of Natural History, and I worked with the National Anthropological Archives, with the archivists there. You have to state in the application what you’re focusing on, and it was going to be about Crow delegations. But when I got there, I was like, “Actually, I just need to see every single thing you have.” [laughs] I had this amazing experience in the natural history museum of looking at Crow objects, just having a really great time looking through everything. Seeing things that were in the photos, things that I thought would be a certain way, I found in reality were totally different.

Something so important that’s come out of that is that I connected with ancestors I never knew I had. I found out that my fourth great-grandfather’s name is Green Skin, and that NMAI has eight of his medicine bundles, and one of those bundles happens to be a horse-getting bundle. I got to hold my great-great-grandfather Bear Tail’s necklace. I got to hold my fourth great-grandfather Green Skin’s deer-ear charms that he would wear into battle. I mean, how crazy is that? Oftentimes, we’ll go to these museum collections that have Crow things, and I’m like, Maybe I’m related to somebody in here, I don’t know. But to actually go to a collection and have ancestors … and touch something that was so important to them, was beyond.

Franco: Do you have any Apsáalooke figures you identify with?

Red Star: I do. I really identify with Alexander Upshaw. He was the interpreter for Edward S. Curtis when he came and photographed the Crow community in the early 1900s. The reason why I relate to him is he was in the first generation of Crow children who left the reservation and got an education. Granted, he had no choice. He went to the Carlisle Indian School. I just read some of his letters to the Carlisle newspaper. There’s a ton of self- hatred in his letters about his identity during his time away from the reservation. And then he went through this transformation, where he came back to his culture and the reservation, and the local newspaper wrote about him—like, he went back to the blanket, which is what they would say about Native people who went back to their culture, back to being Apsáalooke. They went back to the blanket. That would be a great show title.

Franco: You could sew a lot for a show like that.

Red Star: Yeah, exactly, sewing and textiles are so much part of my practice. But, with Alexander Upshaw and the idea of going “back,” I feel like I know what he felt. He married a white woman and got a lot of ridicule for that. I just feel like, Wow, to be that first generation, being educated, coming back, being ridiculed by the Crow community for “you’re not Apsáalooke anymore,” and being told by the white people that you’re going back to the blanket. A lot of the historical chronology wouldn’t have happened or been documented in the way that it was if it wasn’t for him. He just resonates with me, as this nerdy archivist. I don’t even think he was a nerd [laughs]. If I met him, I would probably not even like him. But right now, I think he’s a kindred spirit. I think he was murdered. He ended up dying in a jail cell, because he had a hemorrhage. They found him in a jail cell, dead, with blood everywhere. And he died in his thirties, like young thirties. But he had such an accomplished life. Actually, the way that my ears are pierced is the way that his father’s ears were pierced. His dad’s name was Crazy Pend d’Oreille, which means in French, like, an ear pendant. So, yeah, I felt a connection with Alexander.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Franco: You’re pointing at your right ear, and there are four studs, evenly spaced.

Red Star: It’s basically these three studs up here that are pierced like his dad’s. I’d say I really resonate with him, and then I resonate with my great-great-grandma, Julia Bad Boy, her Apsáalooke name. The literal translation of it is Her Dreams Are True. I found her in the archives at NMAI. I was just like, This name is the best name ever. She is the mom of William Dust, who’s my great-grandpa—and he would be my grandma’s dad. Bill Dust. His Crow name was Sings In The Camp. Then he gave my dad his Crow name, which is Kind To Everybody. I love him for that, because my dad is very kind to everybody, and everybody in the community knows they can come to him, and he will do what he can for you. So “Báakoosh Kawiiléete” is how you say “kind to everybody.” And Bill’s son is named Clive Dust, and I have his Crow name. I asked to have his Crow name, which is Always Creative.

Franco: What does that mean, to ask for a name, and when did you do that?

Red Star: Usually you’re given a name when you’re a kid. Your parents go and ask someone that they respect in the community to come up with a name. And that name usually comes from a variety of places. So my first name is Shiny Shell, which means basically “abalone necklace shell.” The woman who gave it to me, her name is Emma Coffey Smells, and she wore abalone necklaces when she would do the ceremony called a Sun Dance, which is a super intense, three-day thing where you don’t eat or drink water, and you dance all day long. She did, I don’t know, over twenty different Sun Dances. So that is a very powerful name.

But when I got older, I wanted to have a second name. Sometimes men would get a different name if they did something super badass, or if they did something that was notorious. The women or girls didn’t really get a second name. I said to my dad, “I want Clive’s name. How can we do this?” He said, “Well, we’ll ask his son, Clive Junior.” In Crow culture, when you do something ceremonial, you give four items to the person: a blanket; a piece of material big enough to make a shirt, like two or three yards; money; and tobacco. We gave that to him, and then I said, “Can I please have Clive’s name?” We were in the parking lot, in Crow Agency. And Clive Junior replied, “Yeah.” So, now I have his name, Baahinnaachísh, and I’m happy about that. The literal translation is Does Things Well—or “does things in a good way.”

This interview originally appeared in Wendy Red Star: Delegation (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2022), and was adapted from an oral history conducted for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.