Photobooks

What Photobooks Does the Metropolitan Museum of Art Collect?

Home to more than a million objects, the museum’s library shelves are full of surprises.

An experimental collaboration between a legendary Japanese graphic artist and novelist, a book of decorative glass panes, and another with a slipcase in the shape of a cigarette pack. The diversity of books at the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art reveals the flexibility of the form, one that can accommodate endlessly inventive designs and meanings. Home to more than a million objects—which span centuries and include historically significant volumes, contemporary photobooks, and inventive artists’ books—the library’s shelves are full of surprises. As collections librarian, Jared Ash oversees its encyclopedic holdings and works with his team, online and offline, to create a wider appreciation for what a book can be.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Russet Lederman: The Watson Library has a rich assortment of artists’ books. How was the collection formed?

Jared Ash: The Watson Library is as comprehensive as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, maybe even more so, because it’s a lot easier to acquire a book than it is a work of art—and storage is a lot less expensive! For a long time, individual departments, like Drawings and Prints, selectively collected artists’ books, but twentieth-century and contemporary examples weren’t well represented. About eight years ago, a defined collection of artists’ books was formalized to fill this gap.

Lederman: You often share books on your Instagram feed, @MetLibrary. Can you discuss some of the treasures you have highlighted?

Ash: Instagram is an exceptional calling card for us. Our account features unusual materials, especially photobooks and artists’ books that don’t fall squarely within a specific curatorial department’s range, such as object-like books that have inventive formats or include atypical elements made from textiles or glass. By the Piece (2016), by the artist, typographer, and researcher Tabea Nixdorff, is a good example. Printed in a limited edition of twenty copies, it evolved from her research at the Chicago Historical Society and is centered on Agnes Nestor, an early twentieth-century glove-maker and suffragette, who was also a labor rights activist.

Lederman: How does a book like Nixdorff ’s come into the collection?

Ash: We acquire works through different means: about a third are gifts and two-thirds are purchases. Nixdorff and her fellow students were in the city for Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair, and we invited them to visit the Watson Library. We shared some books from our collection, and they showed us some of the works they were exhibiting at the fair. When objects stand out, like Nixdorff ’s book, we see an opportunity.

Lederman: What are some other acquisitions that cross boundaries?

Ash: Sandra C. Davis’s Queen Anne’s Lace (2006) is a small-scale book composed of cyanotypes on handmade Japanese paper, overlaid with hand stitching. A play on words, it tells the history of the wildflower, embellished with lace thread and a real bloom. Clarissa Sligh’s What’s Happening with Momma? (1988), published by the Women’s Studio Workshop, is cut in the shape of a house and illustrated with screenprinted photographic images from a family album. Sligh is an exceptional artist whose biography includes work at NASA and Goldman Sachs alongside her social- justice-focused art practice. In this volume, she explores notions of domesticity and class, elucidating childhood memories through texts printed on folded sheets of paper that drop down like sets of stairs.

Lederman: More recently you acquired the Beijing-based photographer Thomas Sauvin’s Until Death Do Us Part (2015), which is distinctive for its slipcase that looks like a cigarette pack.

Ash: Yes, I believe you could buy this book either individually or by the carton! Inside is a board book of found photographs, sourced from the Beijing Silvermine archive of salvaged negatives from a Chinese recycling plant, celebrating a Chinese wedding tradition where the bride lights a cigarette for each male guest and the couple plays smoking games that include stuffing as many cigarettes in one’s mouth as possible and then lighting them all at once. We value books that challenge people’s perceptions of what a book is.

We value books that challenge people’s perceptions of what a book is.

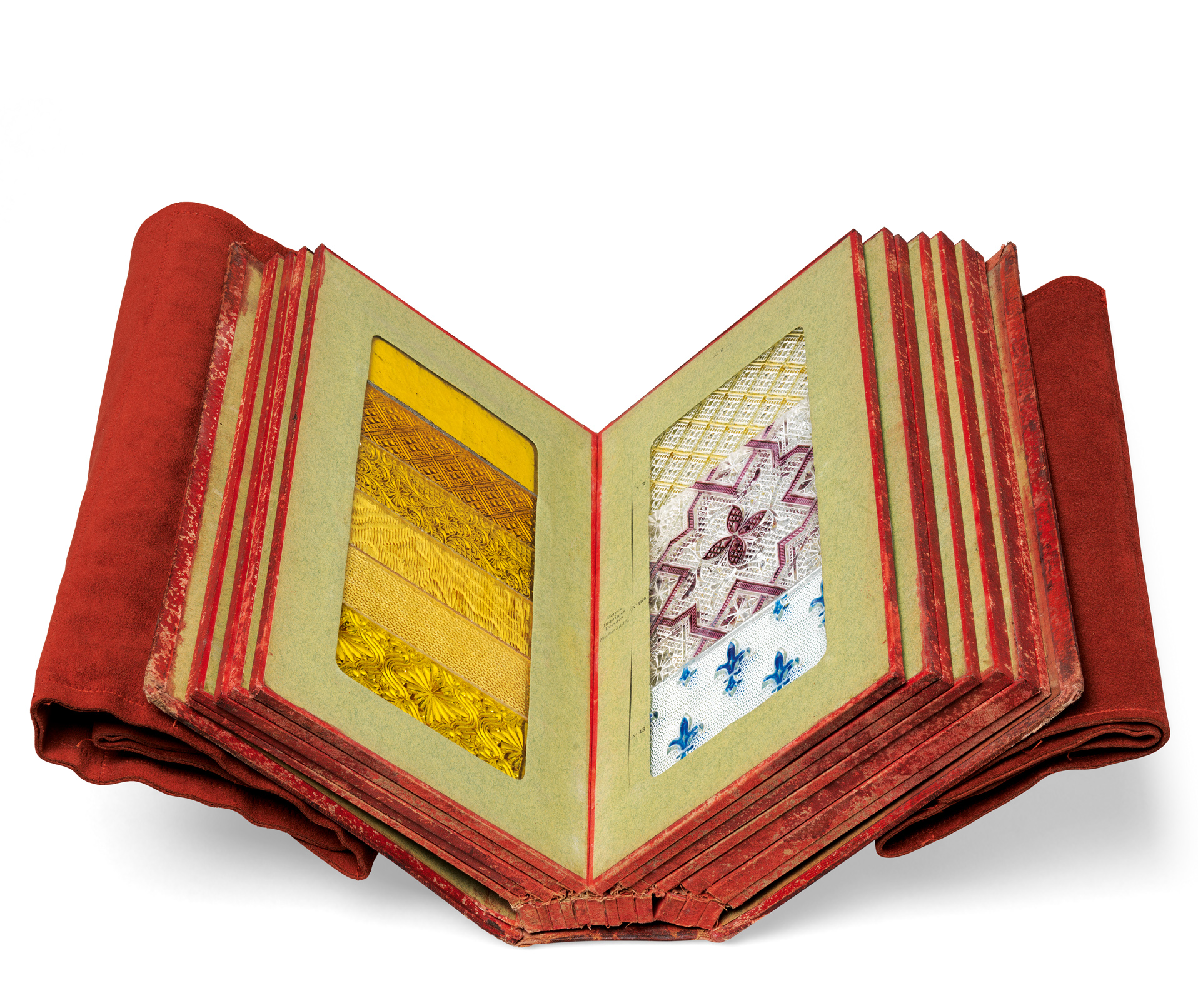

Lederman: Some of the books in your collection did not start as fine-art objects, such as a trade catalog of cast-glass samples that is nearly one hundred years old.

Ash: As part of the twenty-one departmental libraries that are centralized through the Watson Library, we have a substantial collection of trade catalogs. They show how art movements like Art Deco, Art Nouveau, and Constructivism found their way into everyday life, whether on wallpaper patterns or baby carriage designs. This notion of art into life and life into art is important for us.

The Album des principaux modeles de verres: produits spéciaux en verre coulé (1913), a.k.a. “The Glass Book,” is a trade catalog from a French firm, Manufactures des glaces & produits chimiques de Saint-Gobain, Chauny & Cirey, that has made glass for centuries, including for the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. From the outside, the book doesn’t look like much, but inside are pages filled with more than a hundred samples of multicolored decorative glass panes, including the glass that Hector Guimard used for the Paris Métro. It’s a good example of how ordinary materials can be beautiful and inspire wonder. I also really like the backstory of how this book came to us. It was delivered to the library on New Year’s Eve by a book dealer who transported it on his bicycle!

All photographs by Elizabeth Legere. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lederman: More contemporary yet equally inspiring is Irina Popova’s If You Have a Secret (2017). What is its design and concept?

Ash: This book’s inventive design requires activation to discover its message. In this second printing of If You Have a Secret, Popova, a Russian photographer now living in the Netherlands, interweaves personal and public images taken in her former homeland with poems and vignettes printed on semitranslucent, half-cut sheets to reflect on her past life. Most of the text appears on the front of each page, but in several instances, words or lines of type are printed on the reverse side of the sheet— forcing the viewer to hold the book up to the light to read the full text and understand its deeper meaning.

Lederman: Radically different, but just as inventive, is Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata (Yata, the Vagabond; 1975), a collaboration between the designer Tadanori Yokoo and the novelist Renzaburo Shibata.

Ash: I think our Yokoo holdings are a good example of how the Watson Library is a study collection. In this case, we’ve collected an artist in-depth, providing a comprehensive collection for research. During the New York Art Book Fair, a dealer from Japan had nearly an entire booth filled with books by Yokoo, which made us realize our lack. We wound up buying about fifteen books from the dealer, Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata among them. Even without knowing its fablelike narrative, the work can be appreciated for its experimental visual elements and dynamism alone. It never fails to wow people.

Lederman: With so many to choose from, I imagine it is hard to have a favorite book, but if you had to pick one, which would it be?

Ash: The collection that I feel closest to is a series of zines that evolved from Teens Take The Met!, a free, museum-wide public program that we co-organize every year with community partners. For several of these events, the Watson Library partnered with Endless Editions, who brought a Risograph machine that the teens used to make zines. We had a group of Russian teens from Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, this past May, right before Mother’s Day, and one of them made a zine about piroshki that is a tribute to his babushka. Every year, program participants include kids from all over the city, many speaking different languages. These are our future visitors, and this event lets them know that this space exists for everyone.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire,” in The PhotoBook Review.