Photobooks

Why Does the Italian Polymath Bruno Munari Still Spark Joy?

Jason Fulford speaks about the obsessions he shares with the beloved artist and designer.

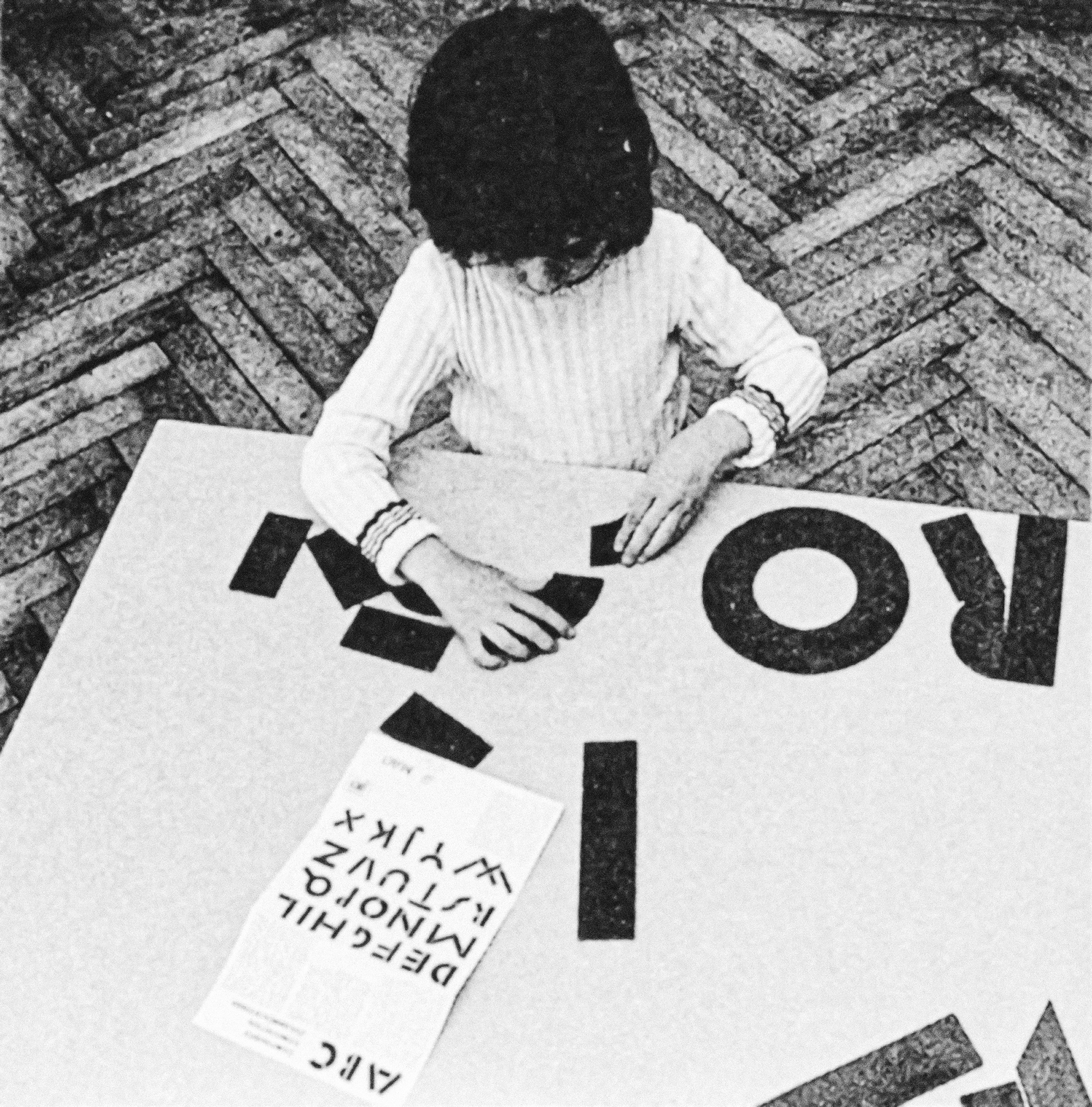

Courtesy the artist

Bruno Munari is a monumental figure in Italian twentieth-century design: a polymath who throughout his seven-decade career seamlessly created book series, lamps, toys, ashtrays, and useless machines (a dig at the Futurist obsession with technology). He taught to adults and children with the same unwavering credos: that art, life, and design should be one, that playing is the best education, and that books make life better. That his path should cross with Jason Fulford, a US photographer and publisher working today, is not strange at all. They share an obsession with open-endedness, a childlike sense of wonder, and a love for the printed page. Luckily for us, the publisher of Munari’s books today, Pietro Corraini, brought them together. Corraini fished unpublished Munari photographs from all over Milan and set up a perfect fotochiacchierata (an Italian wordplay meaning “informal chat with pictures”), resulting in a 2024 exhibition with the same title and a book with a slightly cryptic one: 47 Fotos.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs

Chiara Bardelli Nonino: Why forty-seven?

Jason Fulford: It’s a restriction. I picked a couple of numbers I liked: thirty-three, my favorite, and forty-seven, the favorite number of a writer I used to collaborate with, a good friend of mine who died. I knew that I wanted to add pictures of my own, but they had to be fewer than Munari’s, so out of the forty-seven images, thirty-three are Munari’s. Then I did what I usually do to edit: I printed images out small, and I started to play with them, like a deck of cards. When you do that, you just start to see things, to find connections, to feel a flow. Our images were activating each other, like a chemical reaction.

Bardelli Nonino: Basically, you played a Munari game with Munari. How did you discover his work?

Fulford: A friend gave me and my wife a book about his life, and it just . . . blew our minds. Immediately, I wanted to know more, and the more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

Bardelli Nonino: What resonated with you?

Fulford: The fact that he was a Futurist in his teenage years and left them because he felt uncomfortable with their dogmatic nature. The fact that he always made his own way, that he was really difficult to define. His freedom of movement through mediums, from the hardware store to museums.

Bardelli Nonino: He had a penchant for subverting rules. I remember listening to an interview where he said that to spark creativity in children, you have to teach them a rule, and then tell them to break it.

Fulford: He is a great teacher. And there’s a specific type of play that he does. It’s a play that’s rigorous, that’s both on the surface and deep. It reminds me of a quote from a 1970s novel by Don DeLillo. The character is a football coach in college, and when he’s trying to psych up his team before a game, he tells them: “It’s only a game but it’s the only game.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Bardelli Nonino: Munari was very invested in the idea of democratizing culture. “While the artist dreams of museums,” he wrote, “the designer dreams of street markets.” He thought that there should not be beautiful things to look at and ugly things to use.

Fulford: Almost every year, I teach a workshop in Urbino, in a school that people such as Bruno Munari or Italo Calvino visited, people who remain major influences in Italy. It seemed like they all came out of World War II with a lot of ideas about rebuilding things, redesigning society.

Bardelli Nonino: And making things simpler. Another Munari quote: “Complicating is easy; it’s simplifying that’s difficult.”

Fulford: One of the things that I learned through studying graphic design is how you can take something complex and reduce it to a simple form. I apply it to my photographs: I want them to have an easy entry point, but with deep levels of things the pictures can give you if you spend time with them or if you think about your life through the picture’s filter.

Bardelli Nonino: Have you ever felt intimidated by Munari?

Fulford: I put a lot of pressure on myself. I worked on the book as if I had to show it to him, and I wanted him to be happy with it. I even tried to add some writing into the book, to channel his voice—but it didn’t feel like me, and it didn’t feel as good as his. So I removed it all. What I like to do with images is to show very specific things that are also open. It’s really difficult, at least to me, to do that with words. You either sound totally pretentious or overly sentimental.

There’s a specific type of play that Munari does. It’s a play that’s rigorous, that’s both on the surface and deep.

Bardelli Nonino: Why is this openness so important to you?

Fulford: Probably two things. One is that the aesthetic experience lasts longer. You can think of pictures that expose something or teach you something, but then you don’t need to look at them again. I remember reading Benjamin Buchloh, a German art critic, talking about Gerhard Richter’s paintings as these puzzles that remain a vexation for the viewer, that resist any attempt to solve them. There’s something in that.

Bardelli Nonino: I remember that Munari in an interview was talking about the importance of toys being open-ended, otherwise they kill children’s creativity.

Fulford: I love that.

Bardelli Nonino: What’s the second reason?

Fulford: When I was growing up, I was raised in a pretty intense fundamentalist Christian faith. The only thing I want to preach now is an open mind.

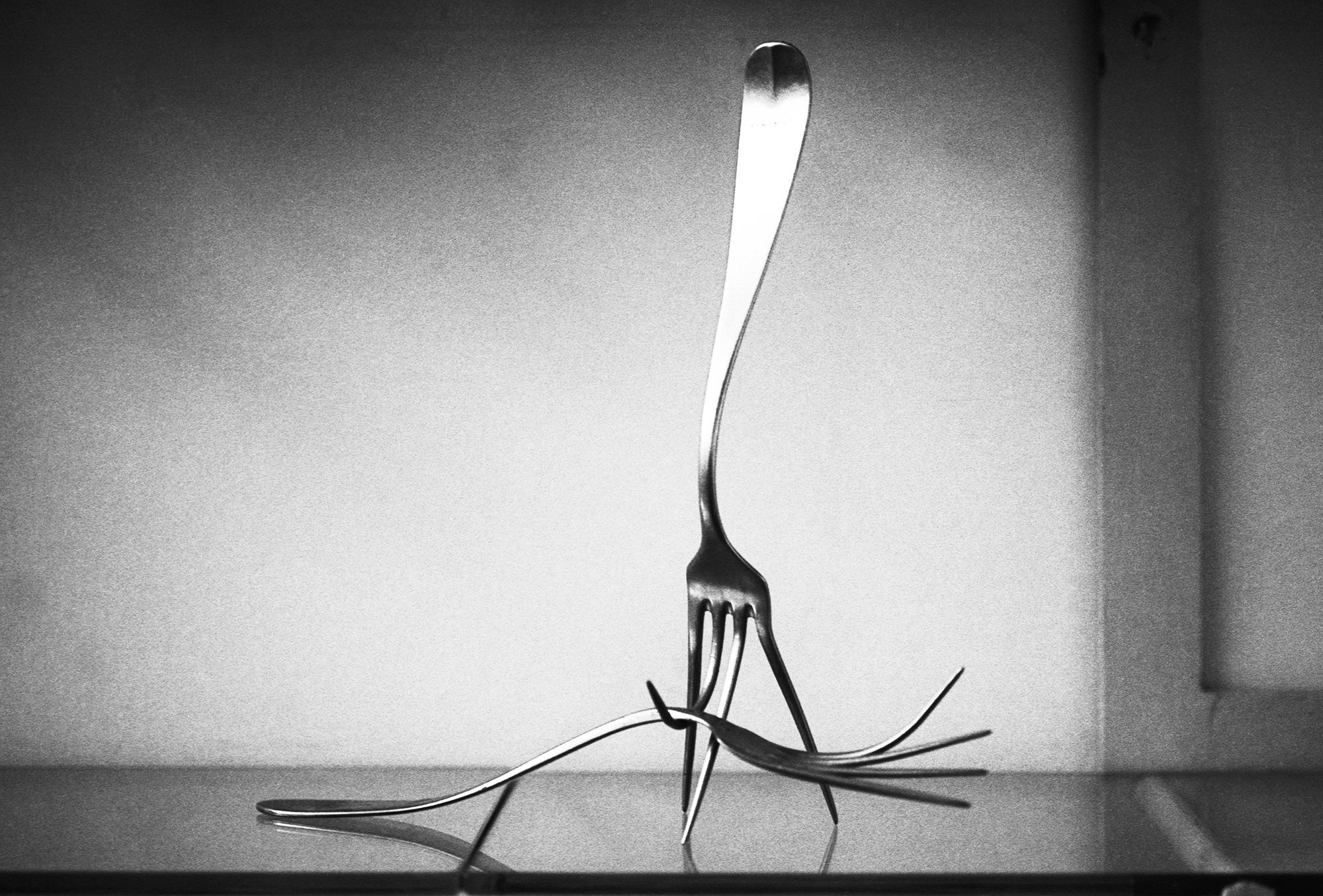

© Bruno Munari and Courtesy Corraini Edizioni

Bardelli Nonino: You know, Munari used to say that his name in Japanese meant “to make something out of nothing.” I think you have a similar approach to photography.

Fulford: I remember talking to a curator once, he was looking at some work of mine and asking questions like, “Why this picture?” And I said something along the lines of, “Oh, I could have just grabbed stuff from the garbage and made something, it would have been the same.” I never heard from him again. But it was true.

Bardelli Nonino: What do you think about Munari’s relationship with photography?

Fulford: I worked on a book last year about Corita Kent, the Catholic nun who became a famous Pop artist, and there’s a lot of crossover. Looking at her archives, I realized that the camera for her was just a tool that was always around. She used it for many different things: to remember something, to make aesthetic images, or as a scanning tool in the process of making silkscreens. Photography was a tool to make something else, in the same way that Munari takes a fork, bends it, and makes it into all these different characters.

Bardelli Nonino: Like in your work, where a photograph can be a whole universe or just there to affect the meaning of another.

Fulford: When I teach, I ask the students to bring images. We print them small, and we put everything into the middle in a big ocean of images. We use them for most exercises, but I don’t let anybody use pictures that they brought themselves. They have to work with other people’s images, so nothing is precious, or definitive. That immediately makes things go faster, looser. As soon as they change the sequence of the images, they realize their meaning changes, that they become alive.

Bardelli Nonino: Photobooks are your primary creative language. Does it ever bother you that they can be kind of niche?

Fulford: It’s hard to say. If you make a thousand or two thousand books, that’s a lot of people but also not many people at all. Numbers are really difficult. People get obsessed with them on social media. Let’s say you have a few hundred people who like something, but you wish it was a few thousand. A few hundred is still a lot of people. I mean, think of how many friends you have.

Bardelli Nonino: Oh, like, three.

Fulford: [Laughs] I was thinking about this today, though. When the Velvet Underground’s first album came out, it didn’t sell very well. But people said that everybody who bought that record started a band, and all of those bands were great. So they had a huge influence. It’s the same with books. You can go back to them at different times in your life, and they tell different stories, because you are a different person. Your book can speak after you are dead, it can find its way to people by accident. I love that a book can do that.

Bardelli Nonino: You can enter into people’s minds through books.

Fulford: That’s why I feel this affinity for Munari —through the printed page.

Bardelli Nonino: What books are you working on now?

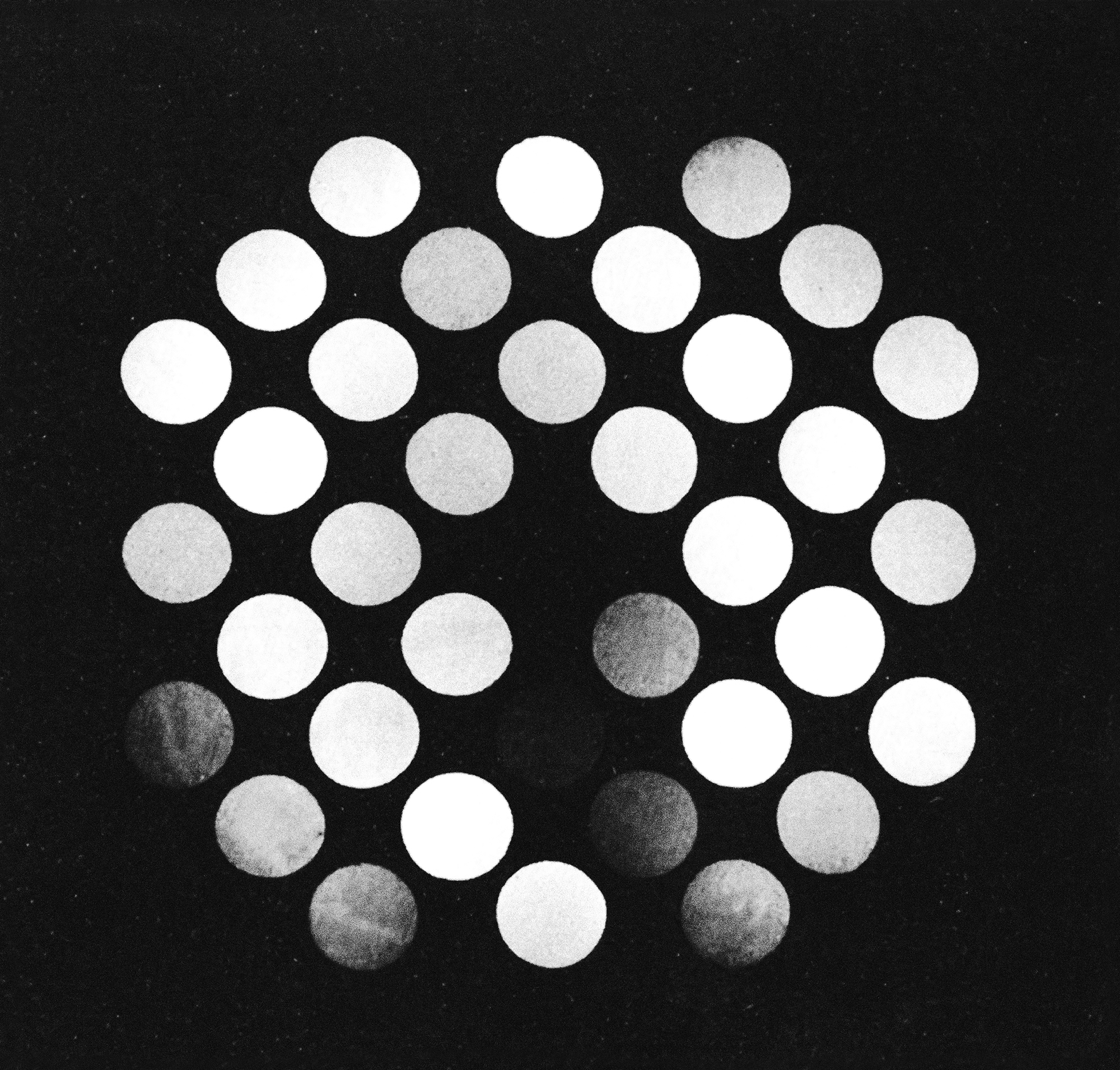

Fulford: There’s one I’ve been working on for several years, and I recently printed it in Italy. It’s called Lots of Lots, and it’s eighty pages of grids of images.

Bardelli Nonino: Why the three-by-three grids?

Fulford: Well, Sol LeWitt made two books that I love, Photogrids, from 1977, and Autobiography, from 1980, and mine reference those a lot, in a whimsical, less conceptual way.

Bardelli Nonino: It looks like a captcha test or a beautiful visual Turing test.

Fulford: I hadn’t thought about that. That’s hilarious. I remember one time I got an email from someone who found my 2006 book Raising Frogs for $$$. He said that he loved how I connected the images, that he was working on this computer-learning model and wanted to replicate my way of working, and asked me if I wanted to get involved. It must have been early AI research. I wrote back an email that said something like: “That sounds awful. It sounds like Satan. Why would I want to do that?” I never heard from him again either.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting,” in The PhotoBook Review.