Interviews

Why Don McCullin Doesn’t Want to Be Called a War Photographer

In an interview, McCullin speaks about navigating the battlefield, his fascination with ancient Rome, and how he finds drama in the landscapes of England.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, Summer 2009, as “Don McCullin: Dark Landscapes,” and was published in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).

Don McCullin is the acknowledged dean of those photographers who have repeatedly witnessed the horrors of war. Working since the 1960s in Biafra, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cyprus, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Vietnam, among other places, his imagery of exhausted and wounded troops, of civilians and soldiers struck with madness, of people starving and ill, reveal in intimate detail many of the agonizing ways in which atrocity can be visited.

Today, McCullin rebels against the moniker “war photographer.” He is not content with the impact of his decades’ worth of images, particularly their insufficient role in diminishing the very violence they depict. The ambiguous position of the image in society is a preoccupation that he has had for a long time, as evidenced by the title of one of his books on the Vietnam War, Is Anyone Taking Any Notice?, published in 1973.

In conversation McCullin speaks passionately, with enormous lyricism, of the revulsion and guilt that remain after years of navigating various borderlines with hell, of his lifelong fascination with photography, of his impoverished youth in a rough North London neighborhood, and of his attempts to heal himself. Recently, he has been photographing landscapes in his native England as well as depicting the remains of the Roman Empire for a large-scale documentary project. While expanding his range as a photographer, he has been editing and printing his previous work, and simultaneously attempting to find some semblance of serenity. —Fred Ritchin

Fred Ritchin: Today we’re going to talk about you being a photographer, a larger career than that of a war photographer.

Don McCullin: I’d like to get away from the awful reputation of being a war photographer. I think, in a way, it’s parallel to calling me a kind of abattoir worker, somebody who works with the dead, or an undertaker or something. I’m none of those things. I went to war to photograph it in a compassionate way, and I came to the conclusion that it was a filthy, vile business. War—it was tragic, and it was awful, and I was witness to murder and terrible cruelty.

So do I need a title for that? The answer is no, I don’t. I hate being called a war photographer. It’s almost an insult. I wasn’t trying to pick up the Robert Capa mantle; I went to war because I felt I was suited to do it. I was young and ambitious, but the ambition started to fade away when I saw people coming toward me carrying dead children, or wounded people coming toward me holding their entrails . . . things like that. Things the average man in the street simply wouldn’t understand, because he’s never been there, thank God.

Ritchin: In the work you’re doing now, the Roman work and the landscapes, it’s as if life has more to offer than simply death. Your sense of time is different. You’re working much more slowly. The time passes over thousands of years. These are traces of things. Before, it was quick, instantaneous, news.

McCullin: It was like what we would call a head-butt. It was about butting somebody in the head and showing them my images. Now I’m behaving in a much more dignified way. Naturally, I’m getting older and coming to the end of my life, so I’ve slowed down. I’ve reinvented myself. The reason I am doing these new landscapes, this new Roman project, is because it’s a form of healing. I’m kind of healing myself. I don’t have those bad dreams. But you can never run away from what you’ve seen. I have a house full of negatives of all those hideous moments in my life in the past.

So now my challenge is the landscape, the archaeological landscape of Rome . . . it’s very challenging and it’s very beautiful. When I can get into the pariah nations—Syria and Lebanon, they’ve eased up a bit, though Syria is a notorious police state—but when I’m there, I am totally safe and alone. I am constantly pushing the barriers, simply for the privilege of getting my cameras out and taking beautiful photographs.

Ritchin: Of stuff that happened two thousand years ago.

McCullin: Yes. Because it’s not as if I’m trying to photograph today’s political struggles. In a way, I am trying to do justice to the culture of these historical sites.

Ritchin: But it seems to me you’re also trying to find a meaning in life, what’s good in life or what’s important, or, as you say, dignified. The war itself is the abattoir. War itself is the meaninglessness of life, and somehow that is there, even in your landscapes and the Roman work. You’re finding something else, something spiritual, some other kinds of answers in life.

McCullin: My landscapes are dark. People say: “Your landscapes are almost bordering on warscapes.” I’m still trying to escape the darkness that’s inside me. There’s a lot of darkness in me. I can be quite jovial and jokey and things like that, but when it comes down to the serious business of humanity, I cannot squander other people’s lives.

Ritchin: Is that because of what you’ve seen in life, or because of where you’ve come from in life? Are you talking about your life as a war photographer, or are you talking about the neighborhood where you grew up—a sense of fairness or fair play?

McCullin: Well, there wasn’t any of that where I grew up. The boys I grew up with were determined to become criminals. I never really wanted to be incarcerated in prison. I spent a few days in prisons in Uganda, and got beaten by the soldiers. Freedom was paramount to my dreams. And in England we have this class structure. It’s very much there—though it’s being exchanged for new racial structures and religious structures that have come in. England is quite a racial country: it was never really on your side if you didn’t have white skin.

So I grew up with all those things, and I’m still living with them, even though I live in the countryside. There are many hurdles in my country; you’re never really going to be free of the hurdles.

Ritchin: But in a way, then, maybe you’ve turned to a kind of poetry of the image, or a kind of lyrical photography, with tonal ranges that are different, more studious, larger formats . . . In other words, you talk about it as informational, the “Roman Empire,” but you’re doing something else. You’re showing the light and the beauty, the metaphors. You’re working in a broader way. It’s like you have a bigger palette now.

McCullin: Yes, it is a bigger palette. The Roman Empire as it was, was extraordinary, apart from the fact that it was based on cruelty and horror . . . You know, when I’m in these great Roman cities, which earthquakes and time have destroyed, I like the fact that I am there, I am enjoying the challenge—but all the time I feel as if I can hear the screams of pain of the people who built these cities. It doesn’t go away. The Roman slaves were paid nothing. All they probably expected was a bowl of food. So when you’re in these remarkable cities, you’re not comfortable really.

You could say: “Well, why are you doing this?” I’m doing it because I have never collectively seen several Roman cities in the Middle East. What I’m getting at is that when I first started as a photographer, I thought: “This is going to be good. I’ll get behind this camera and I won’t have to worry about academia. I’ll just take pictures. It will be easy. And of course, there’s no politics involved!” I’ve done nothing but political assignments in my life. Even going back to ancient Rome, it was steeped in politics and evil.

I feel comfortable doing landscapes in England. I don’t have any apologies, I don’t have problems. And I never do landscapes in England when it’s sunny. I always do them in the winter when the trees are naked. It’s more Wagnerian. I don’t know . . . I like drama and I like darkness.

When it comes down to the serious business of humanity, I cannot squander other people’s lives.

Ritchin: Eugene Smith used to listen to Wagner when he was printing. That’s how he’d stay up for nights in a row, listening to Wagner, and he’d get those deep prints, like yours—deep skies, your dark skies.

McCullin: Well, I was influenced by Eugene Smith, as much as I was by Bill Brandt. I like the great prints that Steichen made. I really studied photography in depth. [I brought a stack of books] home to where I lived, in a Hampstead Garden suburb, and they were as tall as this table—and my God, they were full of information. I used to sit nightly when my children went to bed, studying those books. They became my university. I taught myself everything in photography that I know. Don’t get me wrong about this, I still take a stand—but I am still a student of photography. The moment I think that I have arrived, I’ve had it. I am never going to arrive.

Ritchin: So your life as a photographer, then . . . it’s almost like Crime and Punishment. It’s almost like you’ve created a novel with all these images, from Vietnam, Biafra, landscapes, Rome. There’s something that hangs together. It’s a human struggle.

McCullin: I’ve always been imprisoned in my own struggles. I’ve never known freedom in my life. I suppose most photographers haven’t, really. Life has always been a terrible struggle, even my private life—my marriages, my children, my behavior. So in a way, human struggle has been my biggest factor. I’ve never really found freedom. If I did, I’d probably feel incredibly uncomfortable. Maybe I’m one of those people who is better off in life with someone always tormenting me with the sharp end of a blade.

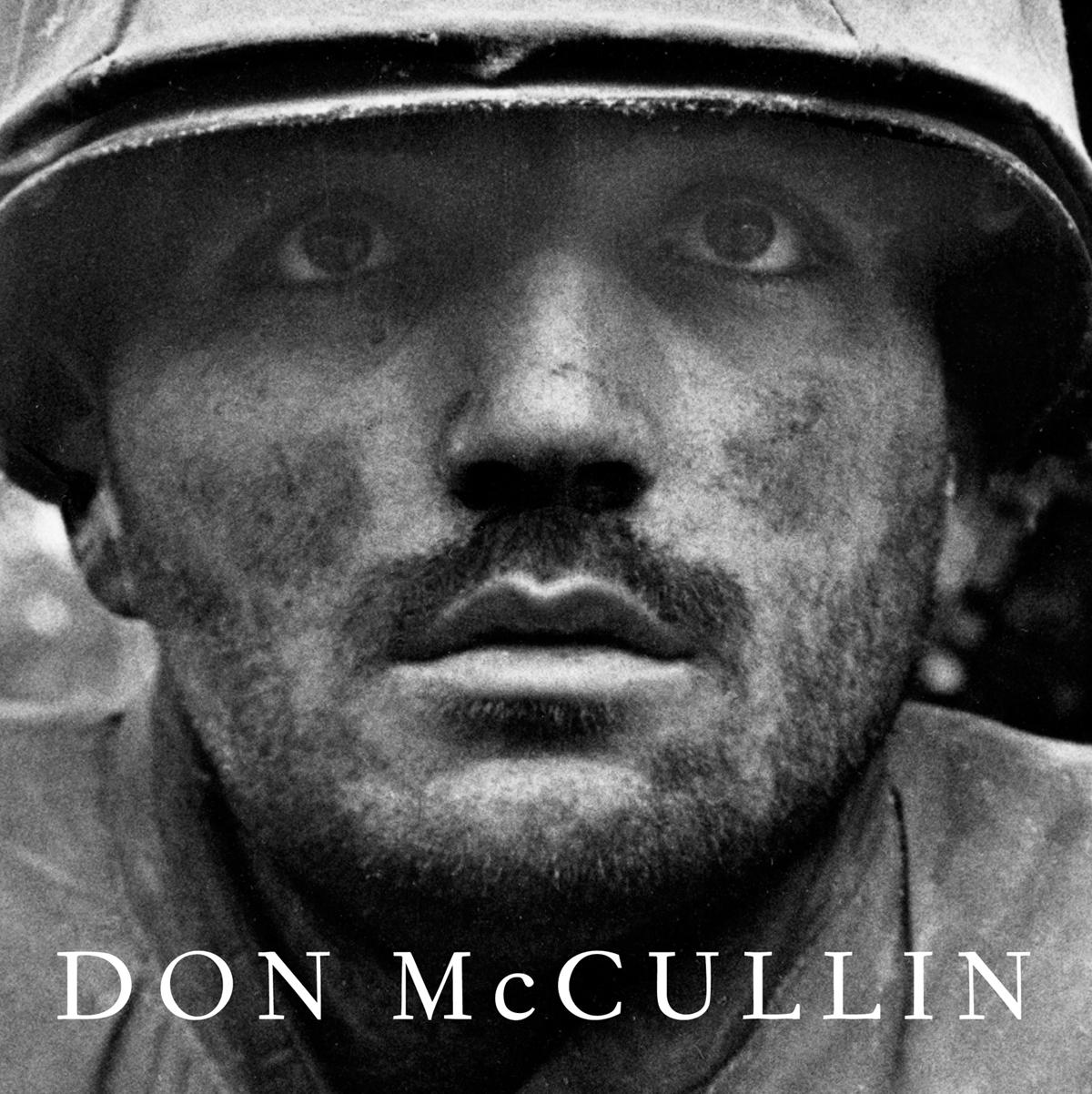

Don McCullin

75.00

$75.00Add to cart

Ritchin: So in your earlier work, you did try to make a difference, with, let’s say, the photographs of war or starvation or illness. Is Anyone Taking Any Notice?, The Destruction Business (1971). And so on. You were very frustrated that not enough people took notice.

McCullin: Absolutely.

Ritchin: I remember you once said that Eddie Adams was the only photographer in the Vietnam War who actually made a difference.

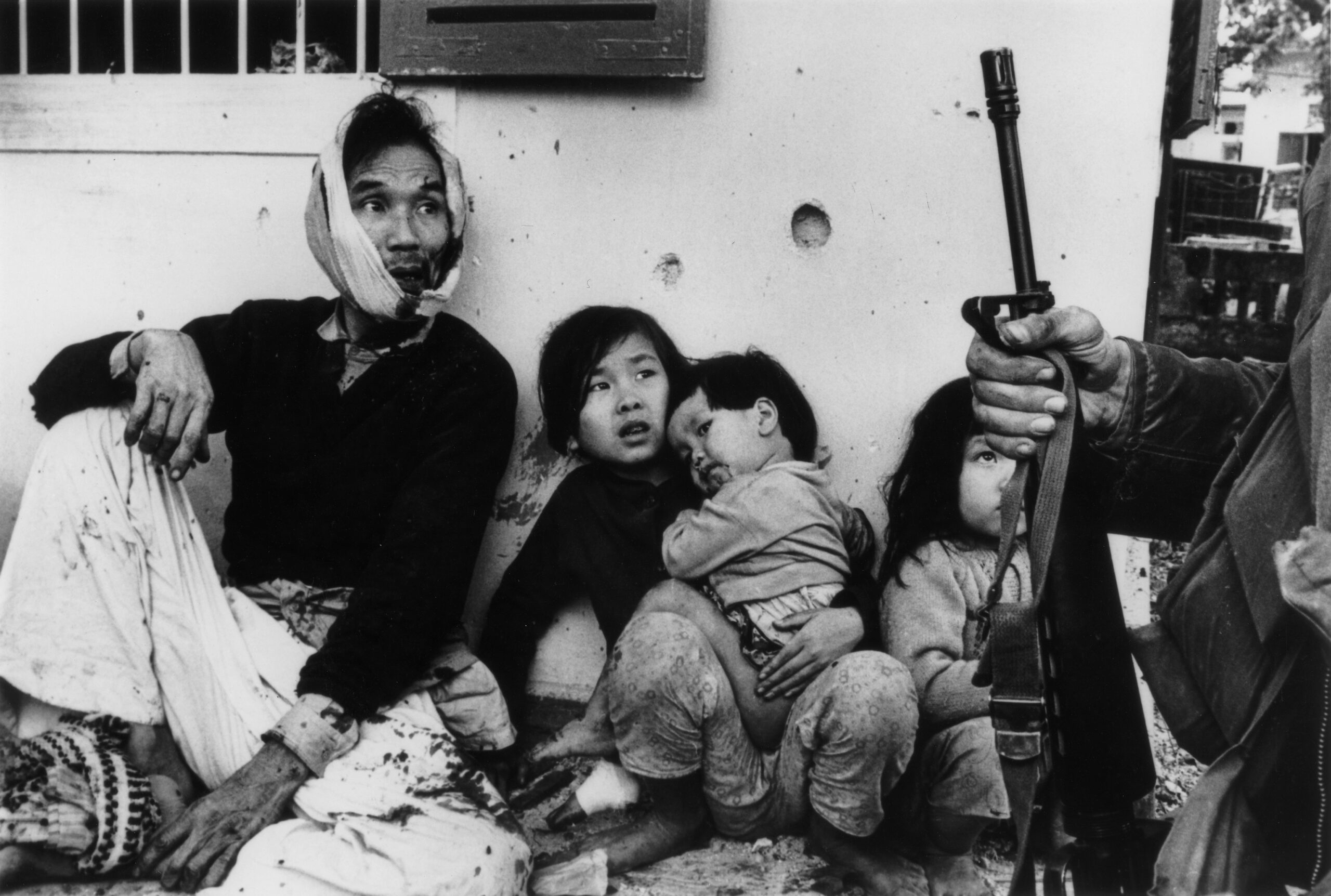

McCullin: It still took seven years for the war to end. But Eddie’s was the ultimate statement. The most famous picture in the war, along with Eddie’s, was [Huynh Cong Ut’s 1972 photograph of] the girl running down the road, burning. These pictures eventually helped to turn public opinion here in America against the war, but it still took years. And if you mount up the casualties in those seven years they would run into the thousands.

So do we make a difference? I have now become seriously doubtful. Because after me came James Nachtwey and others, and then we had Rwanda—and there we go again. There was nothing more horrendous than the massacres in Rwanda. So I say to myself: “No, it didn’t work. We didn’t make any difference.”

Ritchin: But do you think that sometimes people are grateful that you’re there, that somebody does pay attention?

McCullin: No, not really. If you were a fallen man or woman, would you want to be looked upon as documentary material? You’re down here, they’re up there. It’s taking advantage.

Now, I’m really talking to you in a very open, honest way: we [photographers] know we’re doing this. Let’s not make any mistake. We know we’re doing it. It’s not a matter of just happening upon [these scenes]. We sometimes go out premeditating it: we will find these people. We know that we can become well known in photography. We know we can be celebrated in photography.

Ritchin: So there is a mercenary aspect.

McCullin: There is a mercenary aspect. So when I do these things, I am taking along a whole briefcase of psychology up here, knowing that I am on a very fine line. So there is a guilt. It’s like shame.

Ritchin: If you turn to the war in Iraq today, there’s no imagery coming out that’s impacting people in any sense the way that it did in Vietnam.

McCullin: Well, we know why. We had so much freedom in Vietnam. We could do anything we wanted, go anywhere, do anything, photograph anything. [In Iraq,] you can’t photograph a dying soldier as you could in Vietnam, because you have to be “embedded” now. And being embedded is basically like being somebody’s dog who is being taken out to Central Park for a walk with a collar on. So therefore you’ve got censorship, really. That’s what it comes down to.

Ritchin: Young war photographers today become part of a system. And you were trying to disrupt the system. Is it still possible to disrupt the system? Are there other strategies as a photographer? Can you photograph war differently?

McCullin: Well, you know, Philip Jones Griffiths photographed the Vietnam War in a totally antiwar way. His book Vietnam Inc. (1971) was a totally different kind of presentation. Philip spent three or four years there. His book wasn’t about, you know, the Hollywood image of war. It was the real image, the truth of war. So, yes, there’s always another way. There are many ways of photographing war. And you don’t have only military wars. There are wars of poverty, there are wars of degradation, there are wars of hunger, there are wars about crops . . . All these things can be seen as wars, in my mind.

Ritchin: They’re just not as glamorous as the military war.

McCullin: Yeah. But the fact is, we’ve had enough of that anyway. There are so many people now against the war in Iraq. The irony is that [the United States] just signed a contract with the Chinese for oil . . . So there I am talking about politics, which I’ve always tried to keep away from. But in the old days, I didn’t just rush into these areas and get my camera out and have a go. I did the research before I went. For somebody who couldn’t read properly—I’m horribly dyslexic, even to this day—I managed to do it. I managed to get there, and I brought things back. There were always barriers, even in those days, but one got around them.

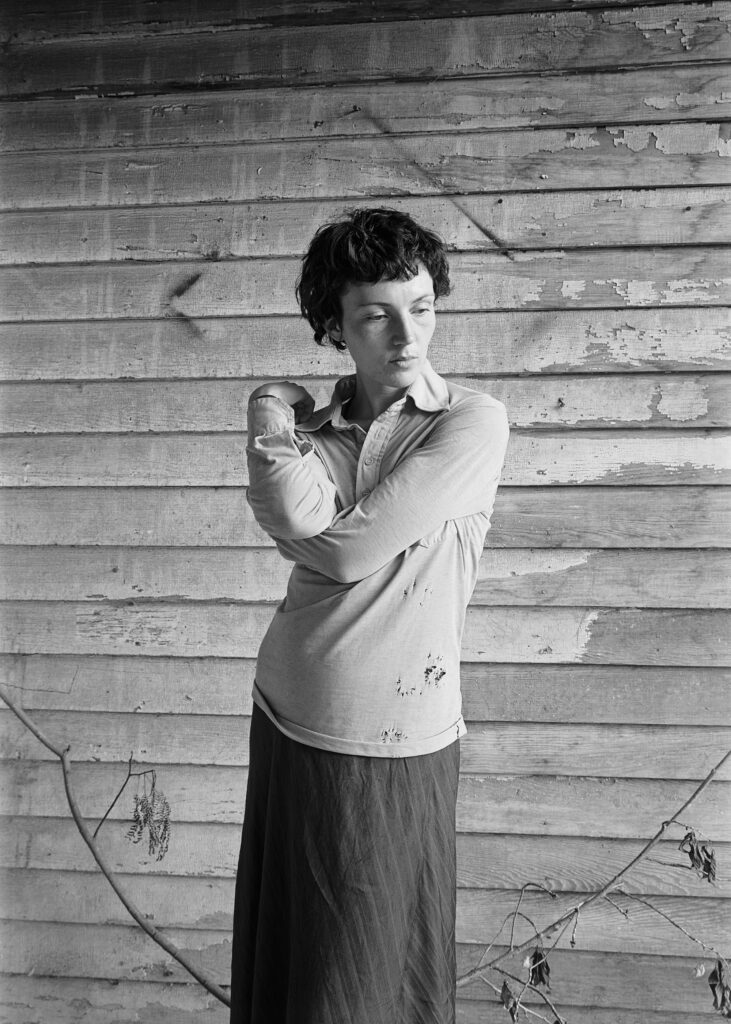

Don McCullin, Poor neighborhood in Liverpool, England, 1961

All photographs © Don McCullin/Contact Press Images

Ritchin: What about digital photography? That’s a whole different process.

McCullin: I don’t do it.

Ritchin: You feel that film says something different?

McCullin: Well, I process all the film as well. I don’t rush things: I wait, I don’t tear the lid off the film-processing tank when it’s being processed, to look at it. I bring it out in a very gentle way, I treat it with great care, and I am very calm. Whereas with the digital camera, you can see what you’ve got from the moment you’ve taken it. I go around the world now, and see people doing that all the time—and I don’t belong there at the moment. I’m interested in film and paper.

Ritchin: But also, I think you’re interested in intuition. Because when you work with film, since you don’t see it immediately, you don’t know if you did a good job or a bad job immediately on the screen.

McCullin: I think I do, sometimes. If you don’t mind me sounding slightly conceited by saying this: you know when you’ve shot a picture whether there’s a good chance of it being the way that you want it to be. If you use a digital camera, it can be that way. But with film, I leave my house, I go all the way across to the other side of the world, I come back with the image, process the film, and wait and wait . . .

I have enormous patience, as I can testify in my landscape work. Sometimes I stay out for two or three hours in the same place, waiting for the sun to go behind those dark clouds. Patience is one of my virtues. Many times I go home without a picture, because at the last minute, the clouds go somewhere else, the sun is beating in my face—I get nothing. You know, it’s like somebody who sits on a riverbank fishing. It’s not about catching fish or getting negatives. It’s about being there, having the privilege to be there and be in command of your own joy. And mind.

Ritchin: It’s a kind of meditation in its way.

McCullin: I suppose. Yes, that’s a better way of putting it. There’s nothing nicer than finding peace of mind, because then it allows you to broaden your mind and then do something better the next time.

Ritchin: Henri Cartier-Bresson thought of a photojournalist as somebody who was keeping a journal with a camera. He was keeping a diary with a camera. It was very personal for him.

McCullin: People would say to me: “Did you ever keep journals?” I’d say: “No. My journals are my negatives. Why would I want to keep journals?” But I can see the point of it. Because when I went to Africa I did start keeping journals. The photograph is not the be-all and end-all. There are other dimensions in life. Lucian Freud is a great painter; that doesn’t mean he has to be a great writer.

Ritchin: What about your autobiography (Unreasonable Behavior, 1990)?

McCullin: That was me talking, really.

Ritchin: It’s well articulated. There’s a lot there, too.

McCullin: I had a good tutor in life. And it was the way I grew up. I grew up with no luxury, no guidance. There was only bigotry and ignorance where I lived—and fists. I could not have had a better start in life! Not that I enjoyed it. But it was the very best start. Because if I’d gone to a university, say, I would never have come out with the same compassion and understanding.

I saw my own father die when he was forty, and nothing hurt me more. So I know about misery and unhappiness: the loss of my father taught me a lot. So here I am. I’ve got slightly further down the road than my father did, but I feel sad that he couldn’t see that I’ve tried to honor his name—by trying to overcome the misery and the poverty and the ignorance. I’ve kind of extended his life, I hope.

Well, that’s just a way of trying to explain to people who might see this that really it’s not just about photography. It’s about being a human being. That’s what it’s about.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, Summer 2009, as “Don McCullin: Dark Landscapes,” and was published in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).