Photobooks

Why Ramón Reverté Believes a Photobook Needs a Great Story

The creative director of Editorial RM has collaborated with Latin America’s most influential photographers. But what makes a photobook a work of art?

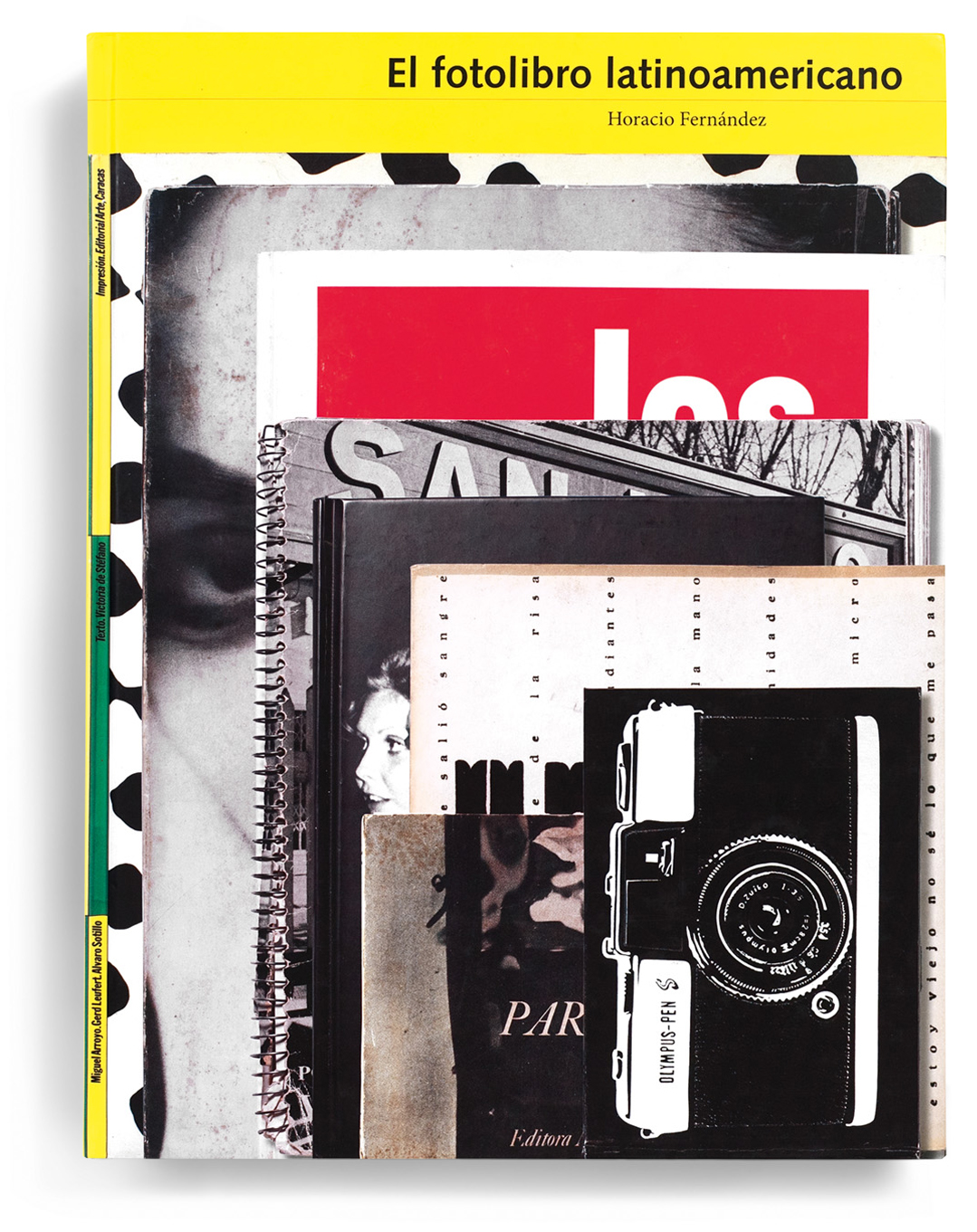

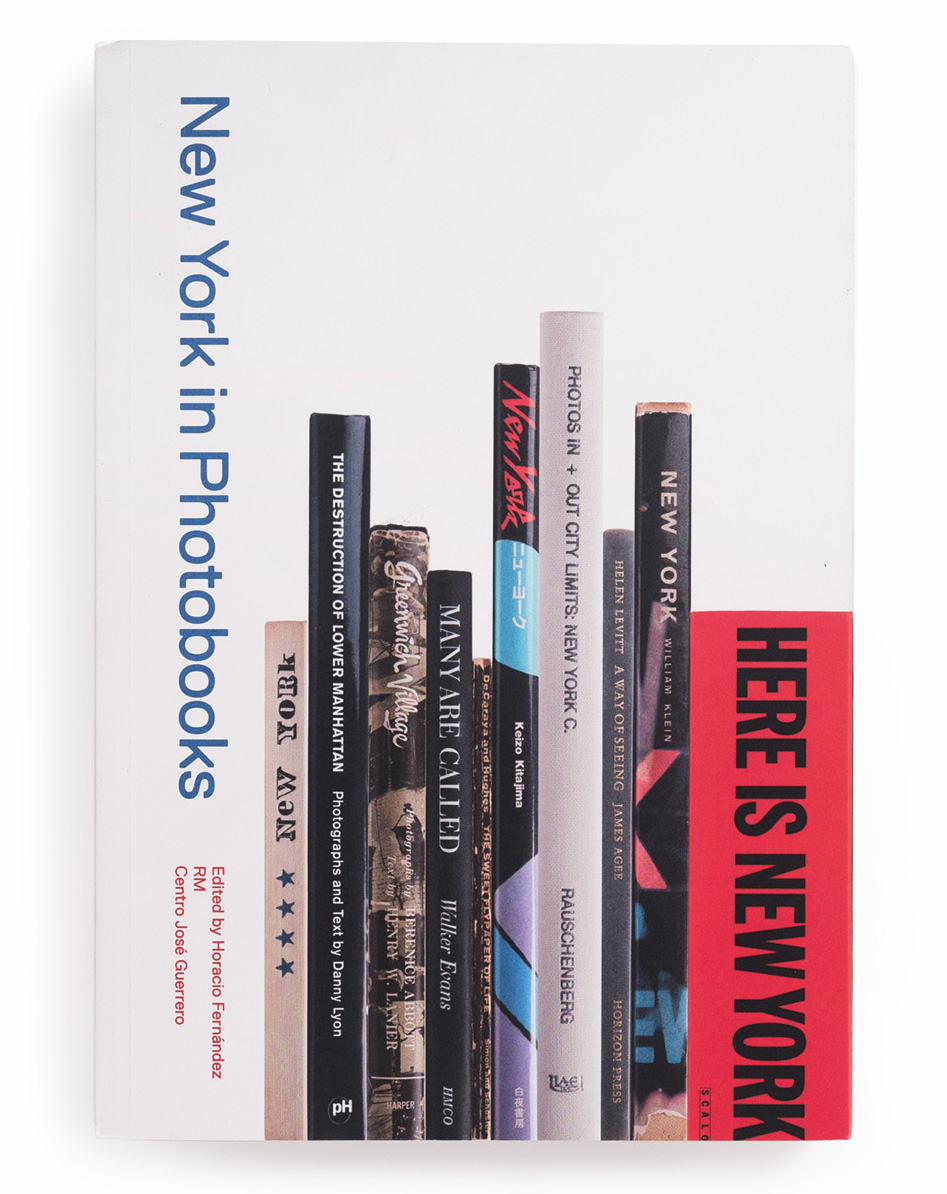

Ramón Reverté serves as the editor in chief and creative director of Editorial RM, a prestigious illustrated-book publisher based in Barcelona and Mexico City that specializes in Latin American art and photography monographs, with occasional ventures into publications that take on the history of the photobook genre, such as El fotolibro latinoamericano (The Latin American Photobook, 2011) and New York in Photobooks (2016). The independent scholar and critic María Minera describes having had “the privilege of collaborating” with Reverté twenty years ago. “I realized that I was, without a doubt, next to one of those editors for whom books, far from being commercial products, took on a dimension close to works of art,” she states. “Every detail, every image, every caption, every comma was studied with the attention that I imagine was proper to the monks of the Middle Ages who made illuminated manuscripts. His works, one after the other, are testimonies of a deep love for those endangered objects that are books in general and art books in particular.” Minera reconnected with Reverté recently to talk about the role of an editor and his unabashed passion for the photobook.

María Minera: Editorial RM is not a publishing house dedicated exclusively to photography, but I get the impression that over the years you, as an editor, have become more immersed in the photographic world, without leaving behind other forms of art. Do you feel this is the case?

Ramón Reverté: Yes. On a personal level, I like everything that has to do with illustrated publications, but what interests me most is photography in book form. Two things have happened: On the one hand, there’s my own focus on photography and my growing knowledge of the genre of the photobook, because I am a compulsive buyer of books. Then there is also a kind of gravity; the more photography books RM publishes, the more people and institutions follow us, and that gives us more possibilities to make books.

Minera: I also have the feeling that in the last twenty or twenty-five years, the interest of the public, but also of the publishing world, in photobooks has grown. There were always photographers interested in the book format because it is ideal to present photographic images, but I’m seeing more and more bookstores filling up with photography books. Do you think so too?

Reverté: Yes, although we have to consider that the photobook was born with photography, going back to Anna Atkins, for example. But it is true that with the publication of Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919–1939 by Horacio Fernández, in 1999, there has been a lot of interest from the public, and especially from photographers, because of the ease of showing their work through a book and reaching other parts of the world. At the end of the day, galleries are in a fixed location. An exhibition is ephemeral. But a book has a very big potential. At this moment, it is also technologically much easier than ever to make photobooks, and there is an average level that is very good. But I would also call it a time of crisis, because everybody thinks they are capable of making great photobooks—and they do not realize that making a photobook is not merely a photographic and design exercise, but that there has to be a very powerful story behind it.

The hand of the editor, the editor who really shapes the photobook, is paramount.

Minera: Yes, you see a lot of uninteresting photobooks right now. Maybe it has to do with the fact that editing is no longer appreciated. Robert Gottlieb, a famous editor, said that the editor’s relationship with a book should be invisible. However, in literature there are very famous cases of editors who told an author to change the end or eliminate a hundred pages. And thanks to those interventions, they are extraordinary books. I feel that we tend to downplay the absolutely essential role of the editor in the photobook. Would you agree with Gottlieb? Should the hand of the editor not be seen?

Reverté: I do not agree at all. I get very involved. Especially in the conceptual part of the book. It’s inevitable that I get into it, in depth. I often select the designer and that clearly directs the book toward a specific style. And, in addition, there are economic factors that constrain a book to so many pages, and to a higher or lower quality of printing. But the hand of the editor, the editor who really shapes the photobook—and I don’t know any good editor who doesn’t—is paramount.

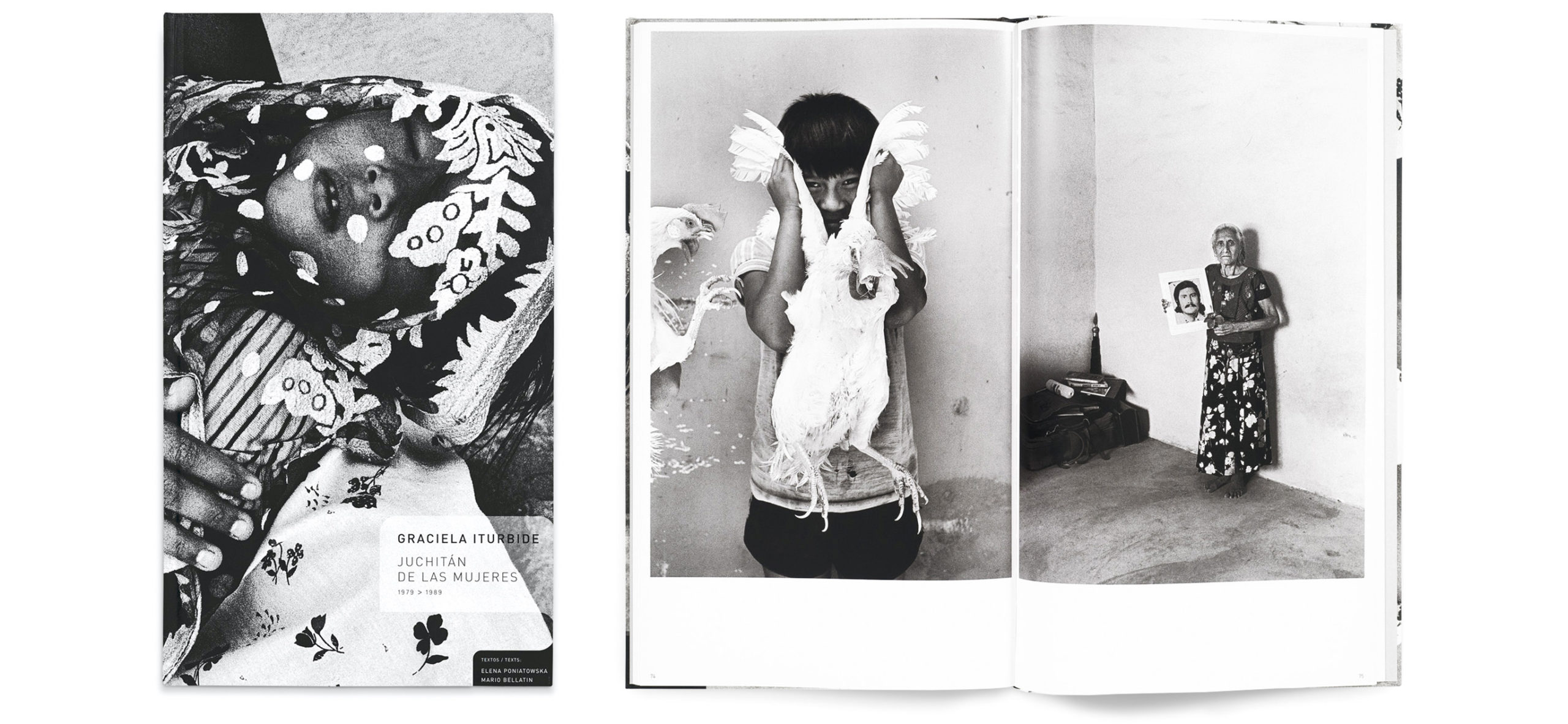

Cover and spread from Graciela Iturbide, Juchitán de la mujeres, 1979–1989 (RM, 2011)

Minera: Do you weigh in on content issues, telling the photographer what images to keep and which ones to remove?

Reverté: It’s never an imposition. I tell the photographer: “Look, you have the last word, but I’m going to tell you with total transparency what I think.” In the end, all books are different. I actively participate and never fail to say something that goes in favor of the book. But there’s a very clear hierarchy, and the one who always ends up deciding is the author. In editing, the problem often lies with images that are not especially good on their own but that are extraordinary when put into a sequence. At times, the author cannot see them because they are too close, too involved. And the editor—because of the perspective they bring—can make those decisions very easily.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Minera: Many authors look to you because they like the books you make and want to be part of that lineage. Do you also develop certain projects yourself ? Could it be that you find some photographs somewhere—maybe at a flea market—and then decide to make a book?

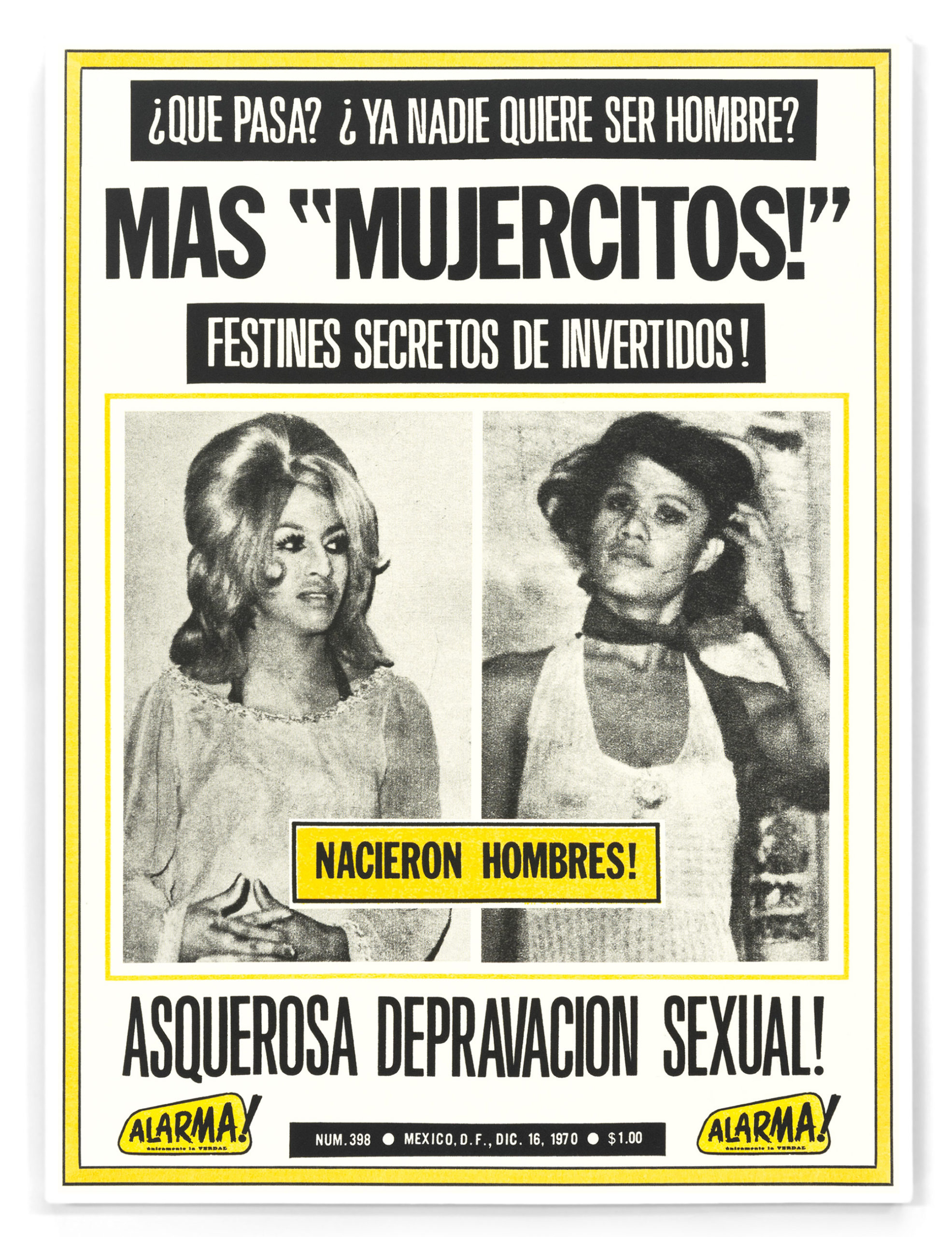

Reverté: Yes, both. Personally, I really like to make books that seem natural to me. For example, Mujercitos (2014) is a book I made with Susana Vargas. She wanted to do a mostly textual book about the phenomenon of photographs of men who dress as women—called mujercitos in Mexico. I said yes, but I suggested a change to the equation: instead of a book with 10 percent images and 90 percent text, we made it the other way around. I also want to make a book by the Spanish photographer Javier Campano, who made a series of incredible Polaroids that I discovered by chance through a friend. I am convinced that it will be a very important book—and by important, I do not mean that it will sell a lot, but that it is a book that is really needed. So, there are books that come ready-made, other books that you propose, some others that come without form and you give them form, others that come almost finished and we do nothing.

Minera: I imagine your passion for collecting photobooks informs your approach as a publisher, right? Did you start collecting at the same time that you began publishing, or was it an earlier interest?

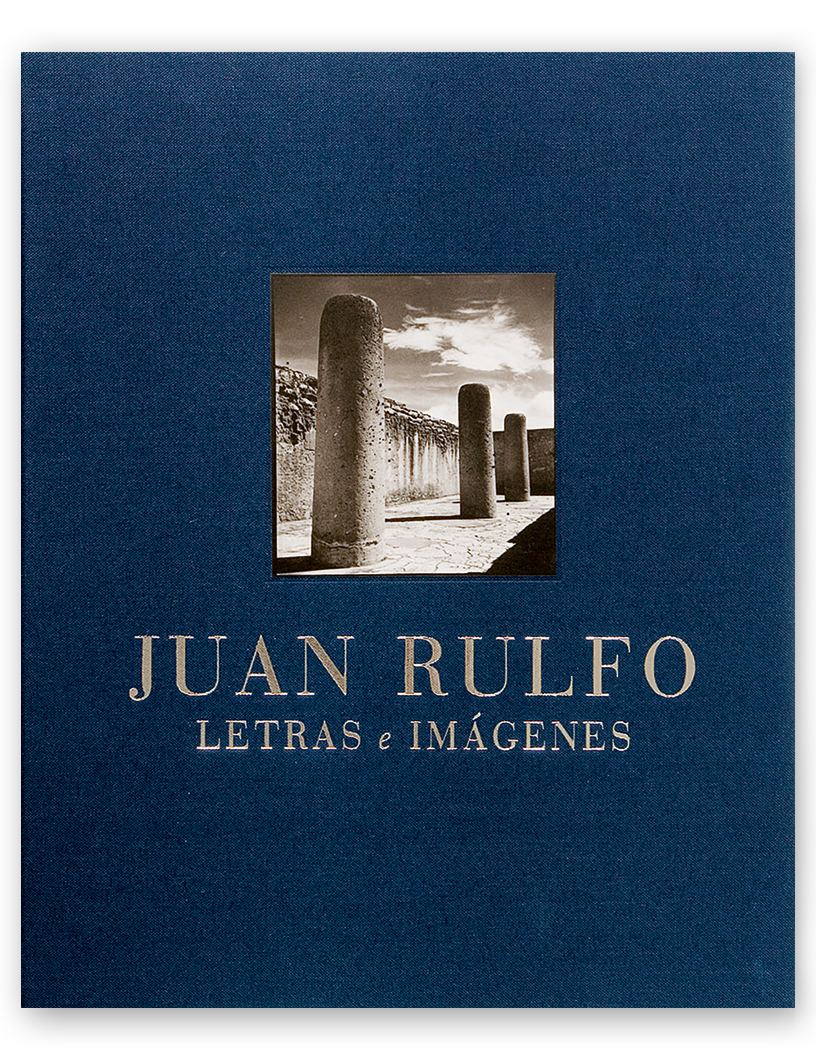

Reverté: It started at a very young age. In my house, as my father was a publisher, Santa Claus always brought us books. So books have always been very important to me. I’ve kept all my books since I was a child, and I keep them in perfect condition. From children’s picture books, I moved on to the world of comics. I have an enormous collection of Spanish comics from the ’70s and early ’80s. And from there came the art and photography book—in general, the visual book. These books give me enormous visual pleasure—more so than reading, actually. From that passion came an interest in making art books. The first book of photography I did, in 2001, was about Juan Rulfo, who besides being a wonderful writer was an incredible photographer. Little by little, things escalated with one opportunity after the other, and a growing closeness to and love for the world of photography.

Minera: You have said that the books you make are the ones you would like to see out there. Part of your impulse as a publisher seems to be the thought of books that do not exist but are necessary.

Reverté: Yes, I don’t fancy doing books that already exist in some way or another. It often happens to me that I am looking for a specific subject, or I know someone’s photographic work and I see that there’s nothing similar around. It gives me great satisfaction to make that book. I publish the books I would like to have.

Minera: With the overproduction of photobooks that we talked about earlier, how do you seek, as a publisher, to separate yourself from the rest? How are you defining a particular path for RM?

Reverté: Well, there is a very clear editorial line, which is, above all, to publish mostly books from Mexico and Latin America and Spain. In other words, our catalog is almost entirely made up of authors from the Hispanic world. That makes us very singular. It makes no sense for me to publish books by French, American, or Japanese authors when there are already incredible publishers in those markets, whereas in Latin America, there is a lot of talent but very few publishing possibilities. Spain is doing a little better now because there are several publishing houses, and it is, after all, a richer country. But not Latin America, so there are extraordinary book proposals that come to us every week from Mexico and Latin America. And unfortunately, we can’t take all of them. We have to be selective.

Minera: And how are those books received in the European market, for example, or in the United States?

Reverté: They are increasingly well received. There is a knowledge that goes beyond the older, classic Latin American photographers now. And also because the language we use when making the books—I am referring to the graphic language—is very similar to the contemporary graphic language of other countries. People understand the language of the book from a design point of view. What matters is that the book is spectacular.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference,” in The PhotoBook Review.