Interviews

Zohra Opoku’s Evocative Reflections on Mortality and Resilience

The German Ghanaian artist weaves together archival images, family photographs, and self-portraiture in works that are often inspired by the city of Accra.

The German Ghanaian artist Zohra Opoku first visited Ghana in 2003, having grown up in East Germany. In 2011, she relocated to Accra, where the emotional and aesthetic inspiration she finds in the city has become a prevailing element in her art. As Opoku says, “Once you are in Ghana, Ghana becomes you and you become Ghana.”

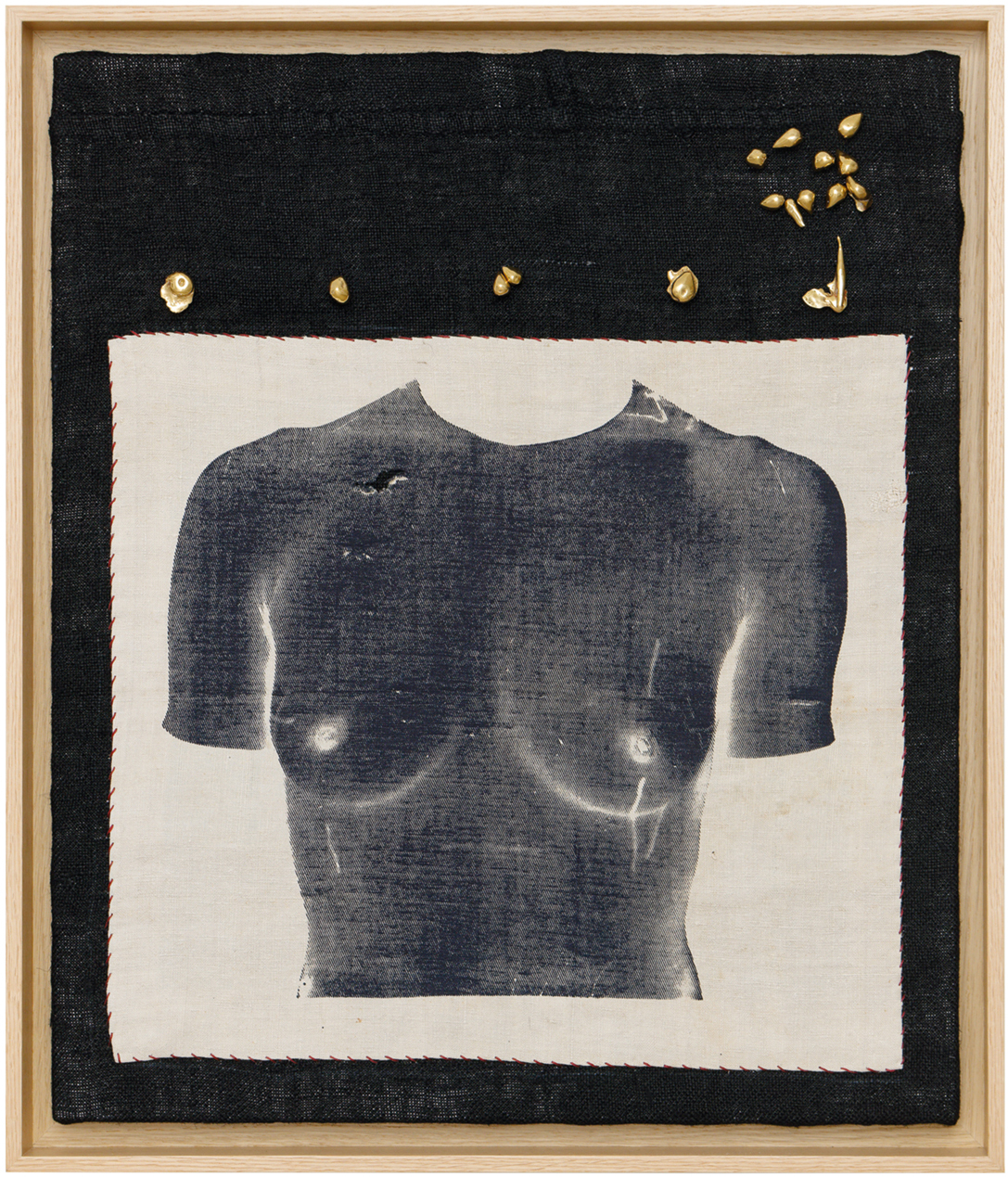

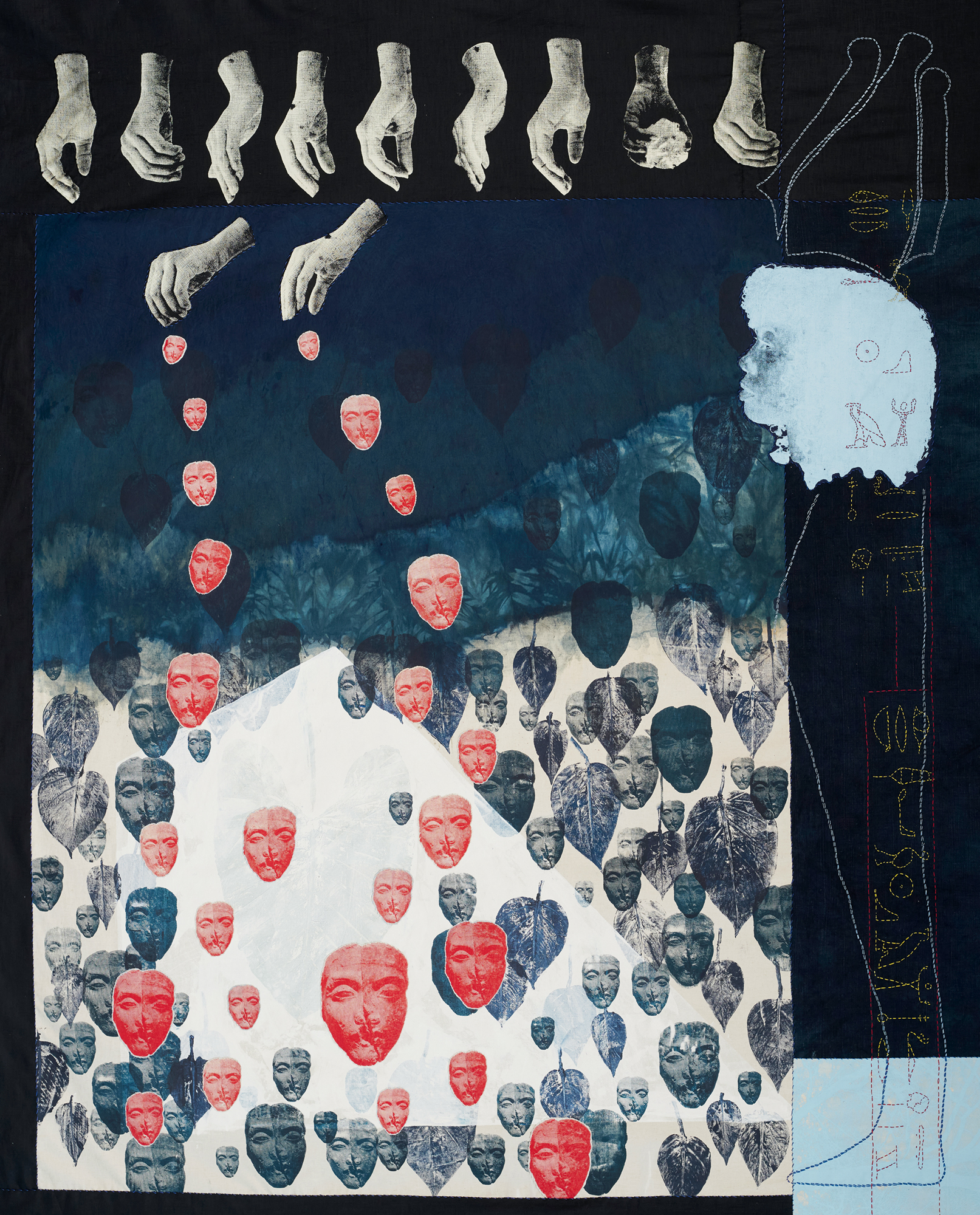

Through a practice centered on textiles and photography, Opoku explores nuanced themes of cultural identity. She prints directly onto textiles, weaving together archival images, family photographs, and self-portraiture to create lyrical composites that marry personal experience and collective memory.

In 2019, Opoku received a diagnosis of breast cancer. She began her most recent body of work while receiving treatment in Berlin and continued its development during an artist residency in Dakar, Senegal, at Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock Senegal program. The resulting series, The Myths of Eternal Life (2020–22), takes its structure and inspiration from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, an ancient text that provides instruction on preparation for the afterlife. Opoku’s art offers lyrical reflections on questions of mortality and resilience she found herself addressing during and after her illness.

Ekow Eshun: Let’s start at the beginning, with you growing up in East Germany. In what ways does that play a part in the work you do today?

Zohra Opoku: The GDR (German Democratic Republic) is now just a subject in school, it’s part of history, something children have been taught. Childhood was amazing, but looking back, I understand how, for my mom, it was an upsetting story, while for my dad it was a devastating story. My father did his PhD in economics in the GDR, and after he had to return to Ghana I was born in Germany. He could write us, come back, try to connect. But then, also, it was a time of no internet and not having phones in the home. When he started studying abroad, it was part of the exchange program developing in East Germany, because for the GDR, Ghana was kind of a neutral country.

Eshun: Part of the socialist states reaching out to the so-called third world at that time.

Opoku: Right. My parents tried to stay connected with letters. My dad could have taken me to Ghana, but not my mom. That was the really sad part. I grew up with a stepdad, and then a single mom, because she and my stepdad got divorced. It was an environment of Caucasian people around me. I tried to explain to myself why I looked different. I made up stories. I was very young, around five. I told my friends that there was something wrong with my baby milk.

Later, when the wall came down and I was able to travel to West Germany, my auntie, who was kind of my mentor, started traveling with me. She took me to London, and it was so liberating because finally nobody stared at me. I felt like I could just disappear. I think that’s where I started to realize that what was missing for me in my upbringing was a connection to my African background. It is always the driving force, this question of identity. How can I relate to the place I’m dealing with? How do I connect? What is familiar? And what do I have to bring to reconnect to the new environment? That’s how my self-portraits actually came out, because it was always a question: What is myself here?

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Eshun: You studied fashion in Hamburg. But with the materials you use, there is a merging of vintage fabrics, photography, and imagery as a way to explore large questions of history and memory, of place and identity. How did you come to this as a way of working?

Opoku: Today, it looks like such an organic process. When I grew up, my mom was always sitting at the sewing machine or knitting; my grandmother was doing embroidery and knitting as well. The handcraft was present in my upbringing. And painting and drawing came naturally to me. Textiles were always around. Later, when I studied fashion, I realized I was already done with it; I spent more time in the photo department than in the fashion department. I was exploring black-and-white photography, especially because it always connected me to my childhood, because all the archival photographs of my mom and my grandparents, and the pictures in our photo-albums, everything that I found was black and white. Even later, when color photography became a modern thing, it was still cheaper to do it in black and white.

Eshun: When did drawing and painting become part of the process?

Opoku: Drawing and painting were always part of it. But I would never actually see myself as an artist. I’ve always thought, I’m a fashion designer. I’m going to be big in fashion. I kept going for many years, doing styling, working for fashion brands, doing window installation, working in design, traveling in Europe, living in Copenhagen and Paris. But I always felt like my soul couldn’t expand; it couldn’t really explore and understand a lot of things. I realized that with fashion, it’s so fast, and too beautiful to seek the truth. As an artist, you always want to excavate the truth of something.

I feel like the body is just existing in a particular time of the life span, but our soul, our being, is continuing.

Eshun: How long have you lived in Ghana now?

Opoku: For twelve years.

Eshun: Why did you move to Accra?

Opoku: It has the energy I was seeking. Since 2003, I came to Ghana maybe every other year. Every time I returned to Germany and arrived at the airport, I felt so empty—something was missing. I just knew I had to find a way to turn it around and visit Germany from time to time.

Eshun: There’s so much emphasis in your art on embroidery and weaving and a handmade sensibility. It seems to me it makes everything very personal—that there’s you in the fabric of all the work.

Opoku: I think the textiles were coming back to me strongly when I started living in Ghana. Everything is textile for me in Ghana. It has so many meanings, histories, and backgrounds that I wouldn’t really feel or be able to touch on in Germany—or understand. Even if I would want to dive into the same topics I’m touching on in Ghana, it’s just not the same energy. It’s like once you are in Ghana, Ghana becomes you and you become Ghana. I was also able to articulate my family heritage, my emotions within my identity, using Ghanaian symbolism and traditions.

And I insist now, when we are describing the works, that people actually understand that everything is handmade. I don’t want to have any machines involved. Today, everything is ultradigital. I wanted to stay within that kind of analog space, similar to how I grew up.

Zohra Opoku, “I have opened the doors of truth. I have passed the waters of heaven. I have raised up a ladder to heaven among the gods. I am one who is with you,” 2023. Screenprint on dyed vintage linen with embroidery

Eshun: You’ve talked before about having an affinity with West African studio photographers such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta—the ways they used fabric as backdrops but also as part of the self-fashioning of their subjects.

Opoku: Absolutely. I have all the books of these masters. In the very beginning, I was even more interested in photographing or portraying other artists or other people, and I used their clothes as a sort of tool to drape around the body, to actually capture an energy. It’s like taking your time and carefully thinking through the process: What does the material say? What does the print say? How does it look in black and white, for instance? Because photographing in color or black and white are two different thought processes. This kind of style, expressing swag, expressing a kind of African soul, being in that space of coolness—that’s something I was seeking.

Eshun: With the family photographs and family fabrics, do you consider these an archive that you’re drawing from?

Opoku: I started to really appreciate this idea of an archive when my dad passed, because he was also a traditional leader. When I created the series, I was working with the old photographs and the textiles from my father. They don’t only give you a material thing—so many memories are burned into that fabric. I realized how heavy the fabrics are, how difficult they are to handle and actually wear, and how my father could walk in them and move in them the whole day. It’s not just a piece of fabric or a cloth. You have to be able to carry them, especially these old, traditional kente; when they are made from silk, they are much heavier than the new ones. In Ghana, a lot of things are not archived, and so, for me, it’s very important to make sure we preserve and take care of them.

Eshun: In your series Self Portraits (2016–ongoing), you are there but not there. Your face is obscured by foliage. What are you exploring in those works?

Opoku: I explore a version of the self, right? I want to look into a social environment, geographical environment, a dialogue with a surrounding. I was at an artist residency in Berkeley at the Kala Institute, and I ended up having more conversations with the landscapes around there, and looking at myself. I was very intrigued by the fact that most of the plants are actually not from that area. They were immigrants, like me. Plants from Middle Europe to the Mediterranean to desert to grassland. There’s this wide range. It was impressive to me how everything could grow in California. And since I have a very strong background of farming and being in nature—my father was also very strongly connected to greenery—nature really represents home to me.

Eshun: In 2019, you were diagnosed with breast cancer, which must have been very difficult. When you started making work in relation to that, you looked to the Egyptian Book of the Dead. What did you find in that book?

Opoku: In the beginning, I was just trying to figure out how to survive, how to get through all these treatments. I ended up in Berlin. I had a bicycle and would ride through parks and go to museums, where I fell in love with ancient Egyptian mythology. That’s how I decided to work with the tomb paintings, the colors, the hieroglyphs. To understand their meanings and the concept of afterlife—and that I can create my own narrative around this.

Eshun: Let’s talk about those trees, because they are present throughout the series The Myths of Eternal Life. You started photographing these trees while you were receiving treatment. They’re in a park in Berlin, but all the trees are bare because it’s winter. They’re yet to blossom and produce new life.

Opoku: What I found interesting is how trees are a metaphor for life and death. I thought, Okay, they can become my protagonist, something that reappears in all the works. By my printing them in so many colors, they morphed into things we can feel or imagine, like veins, or streams of rivers, or greenery, or a kind of energy.

Eshun: They are another form of self-portrait, in a way. We see you with nature again, but it’s a different form of nature now, compared to the Self Portraits series. It’s empty branches and so on. But also, your body is dismembered, as it were, in separate pieces—your head, your arms, your legs. How much is this speaking of your mental state or your physical state at that time?

Opoku: I feel like the body is just existing in a particular time of the life span, but our soul, our being, is continuing. What represents that? And, on the other hand, I found it interesting how hieroglyphs have elements of body parts as a sign language. Now, my pieces are becoming more complex, because I print and cut and apply, then I have the embroidery, and then I have all kinds of practical stitching. There are so many different layers that create the narrative.

Eshun: Did you have in your mind an aesthetic goal for these pieces?

Opoku: The first night after I had the diagnosis, I started dreaming. I never wrote the dreams down but they were present in my thoughts. I realized that something in my work has to reflect that very surreal feeling.

Eshun: What kind of dreams were they?

Opoku: I was dreaming of dying. Dreaming of being buried. Very weird constellations of people around me, who don’t know each other, talking to me about my decisions. Because I decided against the chemotherapy and against hormone therapy. With this, I took a risk but wanted to engage in holistic healing. It’s hard to actually put in pictures. But what I always saw was the sun. That was also something that I always missed in Berlin. That’s why I chose the sun god Re in one of the works. The hands coming from his sun disk are standing for sunrays shining in my face.

I didn’t make a sketch and say, This is how I want it to look. It was like putting it together, step by step, with those elements I had, knowing that in every chapter of the series, I focus on a particular stage of my healing. The last stage, which is the afterlife, was definitely becoming focused on indigo dye, which I was exploring in Senegal, along with darker colors, bluish colors. And in another chapter, dealing with the dead, I was looking into the symbolism of dying. For instance, I learned about the Serer culture, the third-largest religion in Senegal, who used to bury their griots in a baobab tree, which is also known as the Tree of Life. I have two works reflecting on this. I used for the textile piece dead leaves, to print the background as well as to use something that we would actually throw away, but I put some life back in and printed with it. The other work is a brass sculpture of my leg turning into the trunk, and imprints from original baobab leaves are attached to it.

All works courtesy the artist and Mariane Ibrahim, Chicago

Eshun: I’ve never read the Book of the Dead. What’s in it that’s captivating for you?

Opoku: What I love is that you insist on your own truth. You insist on your own authentic being. While you’re entering the afterlife, you have to be honest in front of the council of deities, that you have not done anything wrong, let’s say, which would harm your path into the afterlife on the journey to a new existence.

The translation is so poetic, so beautiful. Then I realized that the tomb paintings, or the drawings in the papyrus, have a lot of poetic elements, corresponding with the words I was reading. That’s why I was very interested in bringing what I liked most in the text into the titles. I’m not very good in doing titles myself, so it was great to have the opportunity to use something that sounds so imaginative and captured the energy of a work. It also took, of course, a lot of reading and understanding what goes well with the piece I wanted to give a title to. That was probably the most important part—that it reads almost like a poem.

Eshun: That’s absolutely the case. The titles are brilliant, such as this one: “I am the terror in the storm who guards the great one [in] the conflict. Sharp Knife strikes for me. Ash god provides coolness for me.” They are mysterious and poetic. But also, the works aren’t illustrative, they are in conversation with these words from thousands of years ago. It seems an extraordinary connection you’ve made with, I suppose, a way of looking at life and a way of looking at death that are contained within that book.

Opoku: When you really digest something, whether positive or negative, something comes out of it. You don’t see it when you start the process, but sometimes, I’m impressed with the result. It’s probably for the best, what happened to me, because I had to go through it, and I had to actually work out a lot in my life. I think by taking time, so much more depth can be achieved, more knowledge and connection. That’s what I appreciate about this body of work—it gave me space to develop my being within a progression.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”