Essays

A Photographer Conjures the Hypnotic Power of Extreme Color

David Benjamin Sherry’s new photobook of mesmerizing, analog photograms, melds queer history, abstraction, and darkroom magic.

Pink Genesis, David Benjamin Sherry’s 2017 series of photograms, was born out of what the artist has called “the transformative potential of the darkroom.” The series title was inspired by James Bidgood’s 1971 film Pink Narcissus, which explores the fantasies imagined and enacted by a male prostitute played by Bobby Kendall. Kendall’s character realizes multiple roles in a created world of spectacular costumes and intense colors, not unlike the vivid colors that Sherry uses in his work. (The film was made over the course of eight years and shot almost solely in Bidgood’s New York apartment.) Amid the shock and horror Sherry felt at the end of 2016, following the US presidential election, he was also energized by the example of Bidgood’s film, in which a small interior space—specifically, a space of queer imagination—can be a site of fantasy and possibility. In his own artistic practice, Sherry also hopes to find a place of alternative possibilities, and in Pink Genesis, the photographic darkroom becomes that place. Following the election, Sherry found himself making pictures while attending protests, documenting the immediate responses of his and others’ communities. But he also felt the urge to turn toward something elemental, in an effort to investigate a new path in his own work, and to find a way forward during a difficult period. It was a time to start from the beginning. As he later reflected, photograms are “the most primal form of the analog photographic process.”

Sherry first experimented with color darkroom photograms in an earlier series, Astral Desert (2011–12). In fact, eleven of the plates in this book are drawn from that body of work, while the rest are from Pink Genesis. In those earlier works, Sherry also used stencils to create areas of color, but the overall compositions of each work were based on the monochrome landscape photographs that were part of the series. Sherry has long been committed to interrogating and reinvigorating a tradition of American landscape photography. In much of his work, he uses a large-format film camera to capture the beautiful wilderness of North America, much like his photographic predecessors. Yet rather than considering an “untouched” sublime that is seemingly immune to human exploitation, Sherry highlights the rapid environmental change of our time, often utilizing saturated monochromatic color.

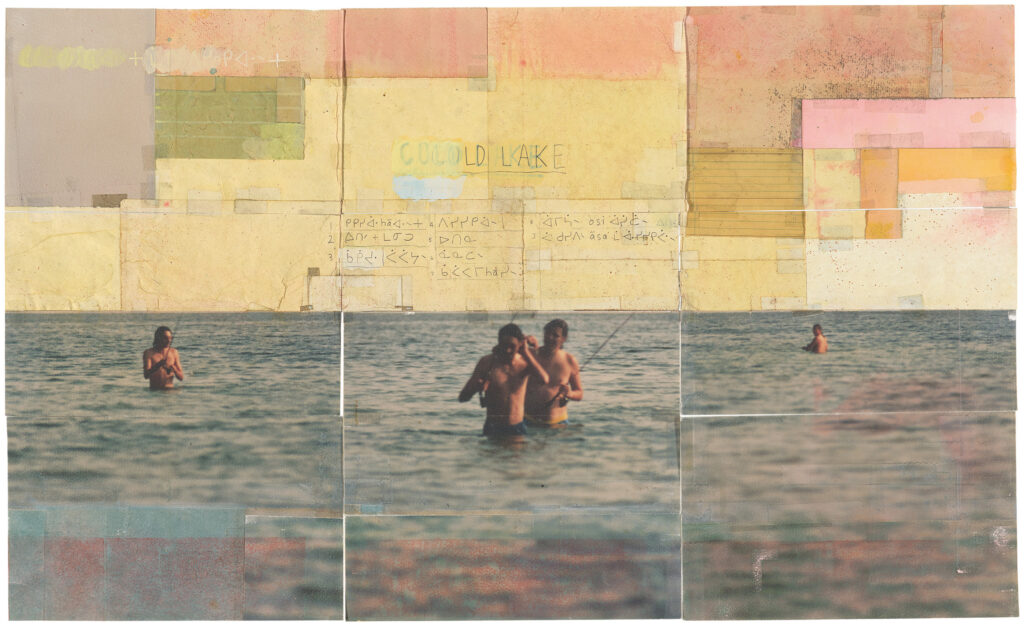

David Benjamin Sherry, Sailing on Solar Winds (Self-Portrait), 2017

Prior to initiating the Pink Genesis series, he was already investigating the ways landscape photography could be edged toward abstraction by removing horizon lines and “pushing color to its extremes to evoke an emotional experience.” He spent 2015 capturing the devastating effects of climate change across the country, and had recently completed the series Paradise Fire, a body of work titled after the massive fire in Olympic National Park, in Washington State, that burned almost three thousand acres that year. The series title pairs those two seemingly contradictory words, paradise and fire—an amalgam that attempts to articulate the incomprehensible toll of humankind’s impact on the natural world.

$150.00Add to cart

$3,000.00Add to cart

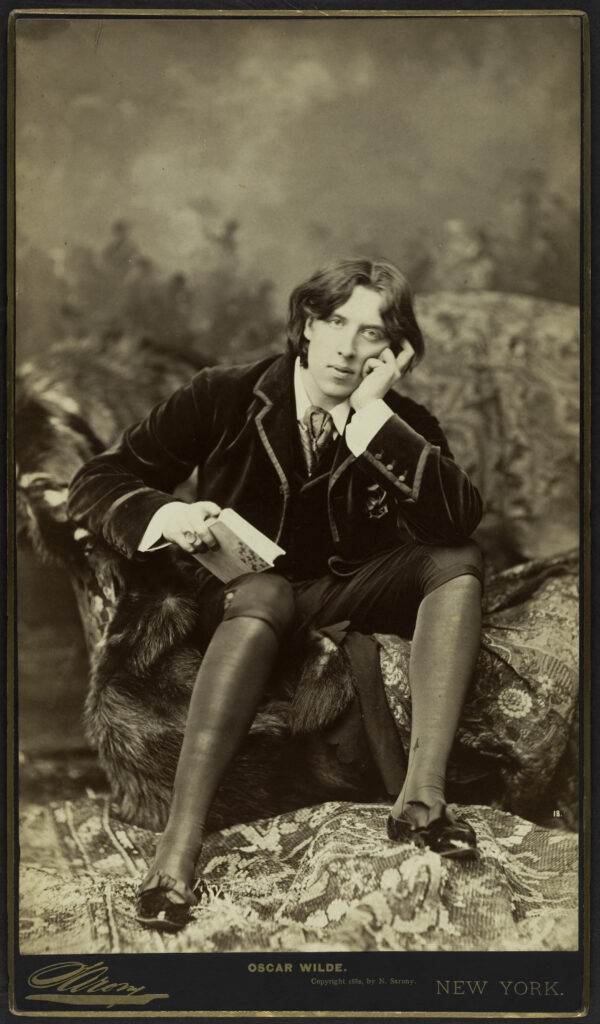

As a queer photographer on the road, Sherry struggled with understanding his own position in relation to that of recognized heterosexual white male forebears, but he found particular inspiration in the work of Minor White, a founder and longtime editor of Aperture magazine. White approached photography with a uniquely personal vision, striving to achieve a kind of spiritual practice, including through sequences in which a poignant portrait might follow a series of abstracted landscapes. “White’s work has been an endless road map of encouragement, power, and comfort on some of my darkest nights while alone on the road,” Sherry has noted. “His work is proof to me that magic is real in the world; queerness is power and the camera can be a tool used to harness the energy.” In the book Minor White: Rites and Passages, which was conceived with White’s participation and published posthumously by Aperture in 1978, passages from White’s diaries and letters are interspersed with what Sherry has called his “empathetic abstractions.” One passage reads, “The spring-tight line between reality and photograph has been stretched relentlessly, but it has not been broken. These abstractions of nature have not left the world of appearances; for to do so is to break the camera’s strongest point—its authenticity.” For Sherry, stripping things down further—rendering images as fields of color, produced through chemicals, light, and time, but without the camera itself—was an opportunity to go back to the beginnings of photography at such a fraught moment.

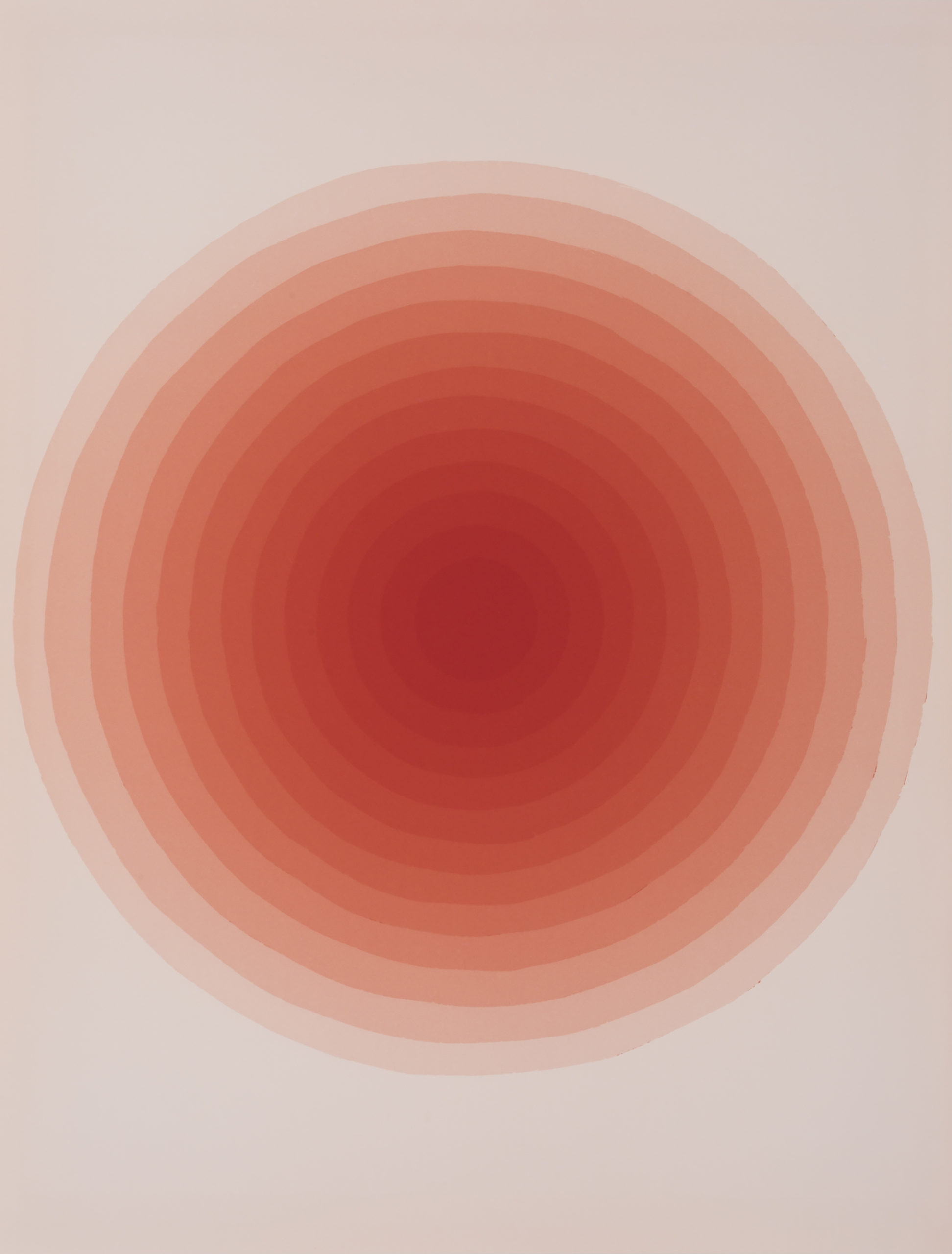

The first photogram made for the Pink Genesis series, Winter, consists of a rich green field with a circular motif at its center. Sherry later realized that this shape, with its round depth augmented by multiple shades of green, approximates the hollow form of a pipeline, an object that was the subject of some of his recent landscape photographs shot in different areas of the United States, inspired by the #NODAPL (No Dakota Access Pipeline) movement. But Sherry understood that he had not just reimagined, in the darkroom, a form that he had encountered in the landscape; the circles held other meanings too: “The work became not only a pipeline but also an escape tunnel, an evacuation route, and a portal to another place.” Other works, such as the pink-hued Sublime Bottom II, further link this motif to the potential of queer transcendence. In this way, at a time when Sherry was acutely aware of himself as a witness to the struggles, environmental and otherwise, within the world around him, the darkroom became a refuge and a place to realize new possibilities.

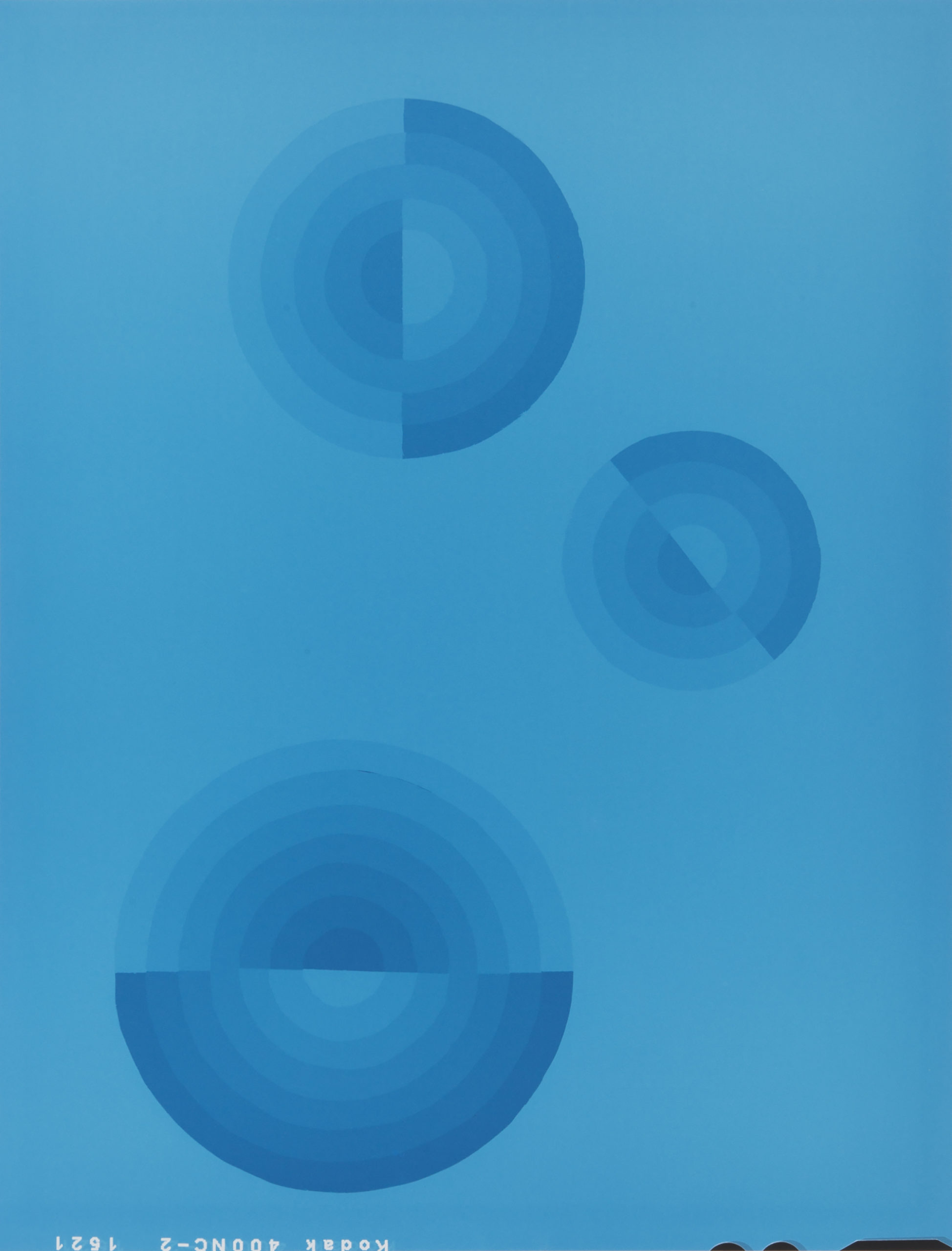

The depth of this portal is intentional. Sherry wanted to find a way to counter the “two-dimensional” quality he had normally associated with photograms. He embraced moments of texture: the imperfect edges of the spheres were the result of hand-cutting his stencils from board. Though the exposure process itself required a great degree of control and precision—carefully counting down seconds, completing multiple steps in a specific order—the handmade character of Sherry’s works is immediately apparent. He has cited the influence of Francis Picabia’s Dada explorations of the 1920s, in which the artist painted depictions of mechanical tools and technical operations; these works left a strong impression when Sherry experienced them in the artist’s 2016 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In Sherry’s photogram Revolution, three circles of different sizes float on a blue ground. Each has been halved and built through concentric semicircles of gradually changing intensity. These pulsating targets might recall the interchanging black and white rings of Picabia’s Optophone [I] (1922), which was titled after an instrument that could read variations in light as variations in sound. Likewise in Sherry’s Revolution, an image rendered from light can be understood through aural tones.

David Benjamin Sherry, Metamorphosis (Self-Portrait with Wizard), 2017

Picabia’s Optophone depicts a human silhouette at its center, and in a number of major works in Pink Genesis, Sherry also incorporates the human form—his own body—by literally climbing onto the enlarger table and putting himself in direct contact with the paper. In Sailing on Solar Winds (Self-Portrait), Sherry overlays an undulating wave pattern onto his own silhouette, playing with notions of space and depth while conjuring the impact of the buzzing energy of those vibrations on the self. In another self-portrait, Metamorphosis (Self-Portrait with Wizard), Sherry achieves a different kind of symbiosis by bringing his dog, Wizard, into the darkroom with him. Sherry has pointed to Robert Gober’s Death Mask (2008) as an important predecessor to his own portrait. Gober’s plaster sculpture combines a cast of his own face with the sculpted snout of his dog Paco, who had recently died, in the tradition of death masks made to keep the image of loved ones in memory. Sherry’s medium also invokes Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg’s collaborative cyanotypes from about 1950, which were largely made on the floor of the New York apartment they shared and which therefore inherently picture their domestic life, just as Sherry pictures himself with his chosen family member Wizard.

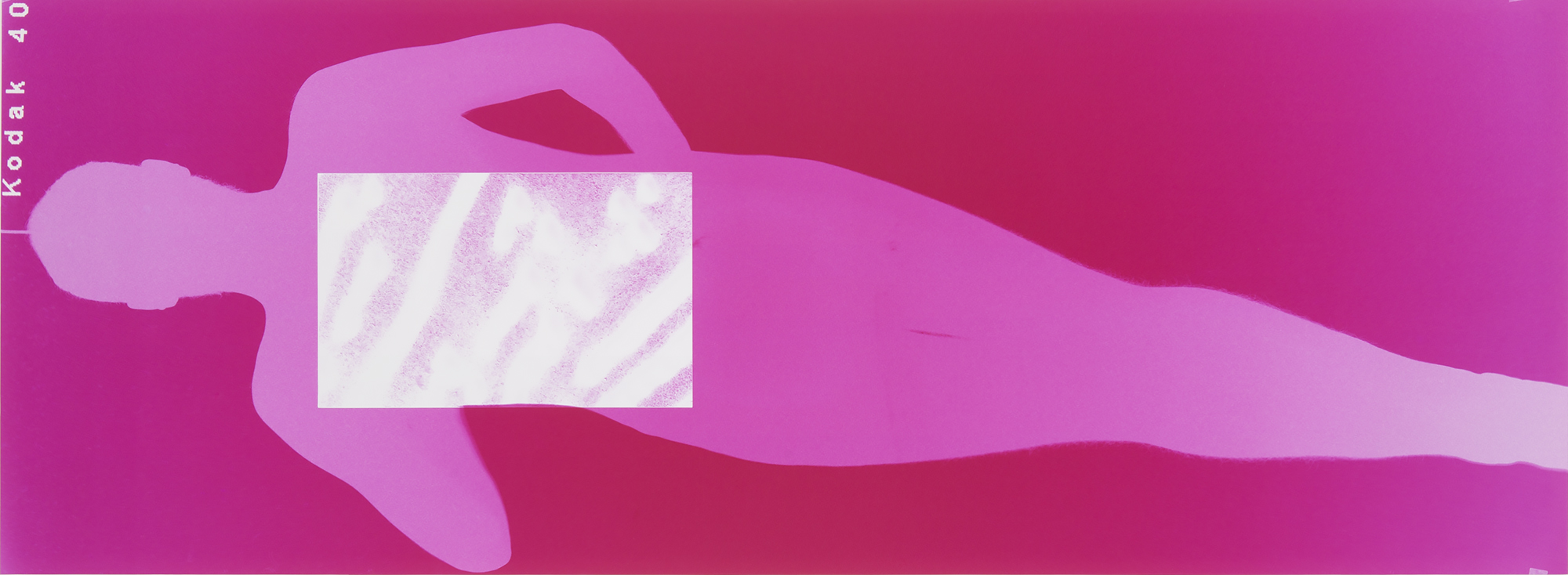

David Benjamin Sherry, Pink Genesis (Self-Portrait with Mars), 2017 All photographs courtesy the artist

“Let the subject generate its own photograph. Become a camera,” Minor White wrote in another excerpt quoted in Rites and Passages. Of course, Sherry typically photographs outdoors with a large-format camera, a process that requires a physical relationship with the apparatus. But to make his photograms, that tool is put aside and the process is pared down to the essentials; he works with only the paper and chemicals in the darkroom itself. In the titular work from the series, Pink Genesis (Self-Portrait with Mars), Sherry’s long figure stands out against a deep pink background. His arms are positioned such that he appears to hold a rectangle of light in front of his chest, a white shape filled with a texture that he appropriated from a NASA photograph of sand dunes on Mars. Sherry is holding in his hands the fantasy space of another world and harnessing the possibilities of emerging anew.

This essay and photographs originally appeared in David Benjamin Sherry: Pink Genesis (Aperture, 2021).